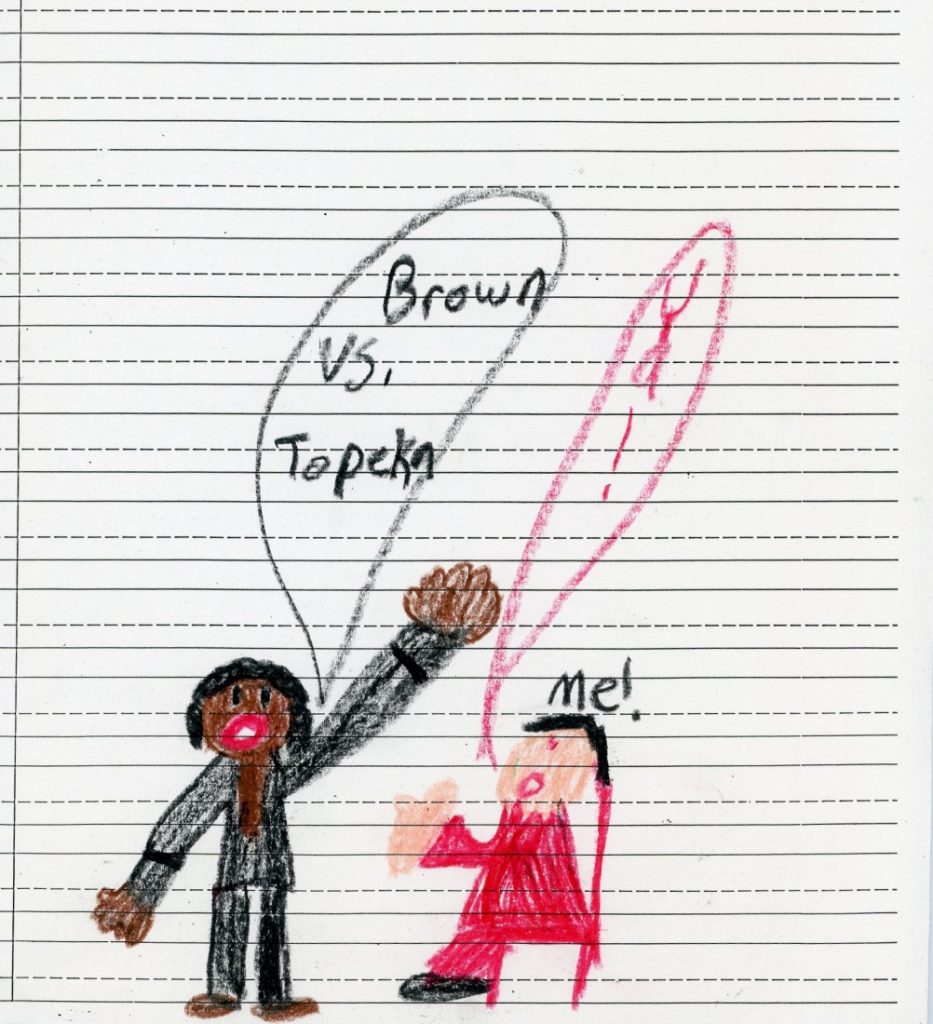

Manuscript of the Month: Tracking the Two-Hundred-Year Ownership Trail of a Fifteenth-Century Manuscript

April 28th, 2021N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS D2 is a fifteenth-century paper manuscript that contains the Epigrams of Martial (Marcus Valerius Martialis, approximately 40 CE–approximately 104 CE). Originally written to celebrate the opening of the Colosseum in the year 80 CE, the Epigrams are a series of short, satirical poems reflecting different aspects of Roman life. In this manuscript the Epigrams are prefaced by a letter written by Martial’s contemporary and friend, Pliny the Younger (61/62 CE–114 CE), to another friend, Cornelius Priscus, on the occasion of Pliny hearing of Martial’s death. According to a colophon found at the end of the text, MS D2 was copied by Jacopo Tiraboschi of Bergamo and was completed on October 19, 1470, probably somewhere in Italy.

![Image showing the colophon in MS D2 on folio 184v, in which the scribe mentions their name (“Iacobus Tirabuschus B[er]gomensis”) and the date of the completion of the copying of the manuscript (“MoccccoLxxo die decimo nono Octobris”) in Martial, Epigrams, Italy (?), October 19, 1470. Call # MS D2.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/KSRL_MS_D2_folio_184v_detail-1024x683.jpeg)

We do not know any other details about the circumstances in which MS D2 was copied nor do we have any information on the whereabouts of the manuscript during the three or so centuries after its completion. The history of MS D2 in the past two centuries, however, is rather exciting and can be reconstructed, especially by consulting modern sale and auction catalogs of manuscripts. Provenance (previous ownership) of manuscripts is an important branch of historical bibliography that has gained more and more prominence in the past few decades. The bedside book for provenance researchers, beginners and experts alike, is David Pearson’s Provenance Research in Book History: A Handbook, which was recently published in a revised edition. The most important resource for those interested in the history of any pre-1600 manuscript, moreover, is the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts, an ongoing, community-driven project to track the historic and current locations of manuscript books across time and place. Initiated by Lawrence J. Schoenberg in 1997, the database is currently managed by the Schoenberg Institute of Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries under the direction of Lynn Ransom.

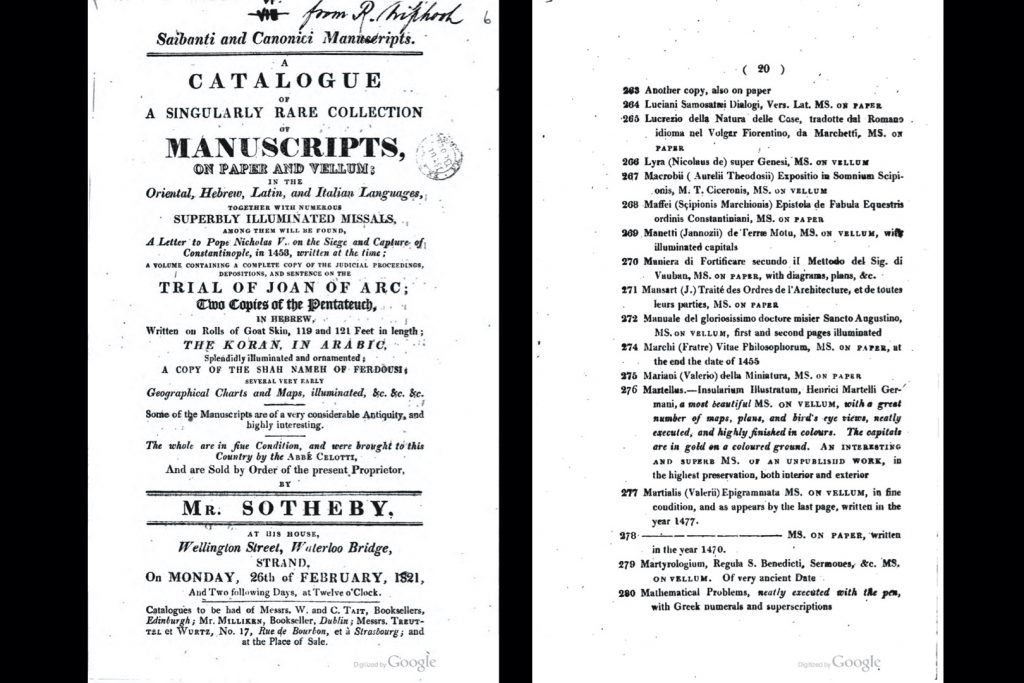

The first trackable mention of MS D2 comes from a Sotheby’s auction catalog dated to February 26, 1821. The long title of the auction catalog indicates that this “singularly rare collection of manuscripts” previously belonged to “Saibanti and Canonici” and that the manuscripts were “brought to this country [the United Kingdom] by the Abbe Celotti.” Abbé Luigi Celotti (1759–1843) was a Venetian abbot who later became a book dealer and this three-day 1821 auction, which included 542 items, was one of his earliest and most important sales. There is no indication in the catalog as to which manuscripts originate from the collection of Matteo Luigi Canonici (1727-1805) or from that of Giovanni Saibante of Verona (flourished first half of the eighteenth century). Both Canonici and Saibante were Italian book collectors and several of their manuscripts were either auctioned off in Britain or purchased by British collectors in the nineteenth century. Based on the name of its scribe and its Humanistic script, it is very likely that MS D2 was originally produced somewhere in Italy and it almost certainly did not leave Italy until it was put to sale by Celotti through Sotheby’s in this 1821 auction.

Following the 1821 auction in London, the manuscript is listed in the inventories of a number of booksellers and appears to have entered into the collections of a series of prominent British book collectors. The next mention of MS D2 is found in the 1836 auction catalogue of the manuscripts that previously belonged to Richard Heber (1773–1833), an English book collector. Heber presumably purchased the manuscript from Celotti at the 1821 Sotheby’s auction. In the 1836 auction of Heber’s manuscripts, MS D2 was purchased by Thomas Thorpe (1791–1851), a well-known bookseller in London from the 1820s until his death. In fact, MS D2 bears an inscription on folio 186v that reads “Thomas Thorpe.” Immediately after, however, during the same year, the manuscript was purchased from Thomas Thorpe by Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792–1872), who had Payne & Foss, another London-based bookseller, purchase several other manuscripts from the 1836 auction of Heber’s collection. I have previously written about one of those manuscripts, now with the shelfmark MS C247, which is also part of the collections of the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Indeed, there are over a hundred manuscripts from the former Phillipps collection currently housed at Spencer Research Library.

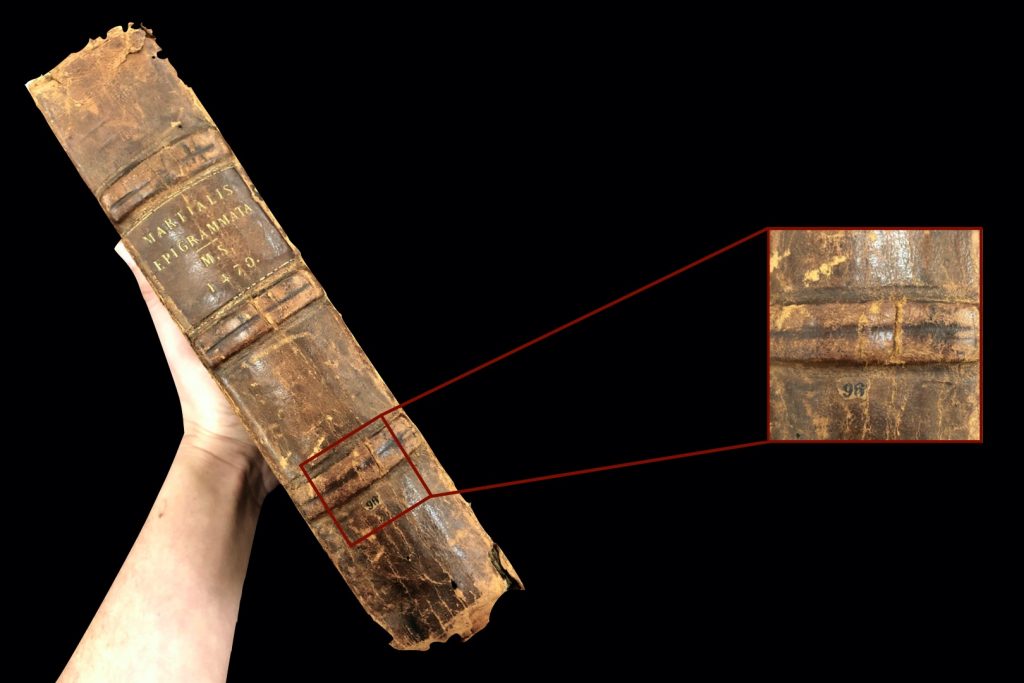

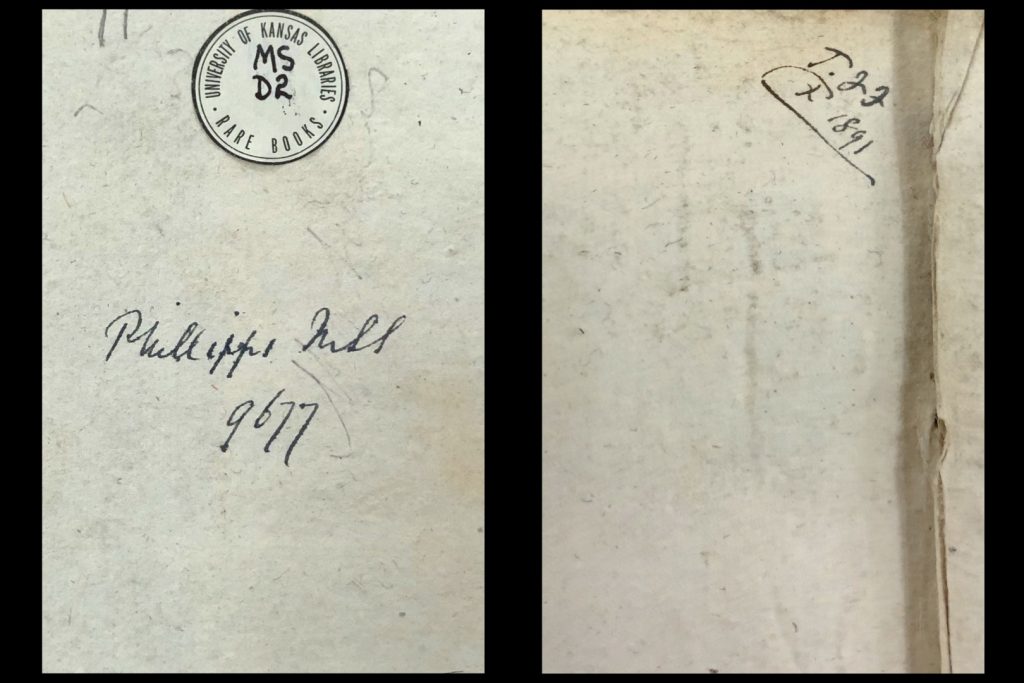

With an estimated forty thousand printed books and sixty thousand manuscripts, Sir Thomas Phillipps had the largest private manuscript collection in the world at the time. MS D2 is inscribed “Phillipps MSS 9677” in ink on the front pastedown and there are remnants of a rectangular Phillipps label with a typeset number, with only “96” remaining, adhered to the tail of the spine. The Phillipps numbers, both in the form of a paper label adhered to the spine of the bindings and as handwritten notes, usually on the first couple of leaves of manuscripts, are one of the identifying features of manuscripts that once belonged to Sir Thomas Phillipps. MS D2 has a modern binding but the fact that there is a Phillipps label on the spine suggests that the medieval manuscript was already rebound with its current, modern binding when this manuscript was being accessioned into the Phillipps collection. There is a binder’s ink stamp belonging to John P. Gray & Son Ltd., a bookbinder based in Cambridge, in the lower left corner of the back pastedown. However, there is no date associated with this stamp and it is likely that this was the result of a repair undertaken rather than a full rebinding of the manuscript.

After his death, Phillipps’s library was inherited by Katharine Fenwick, his daughter, and was later passed on to Thomas FitzRoy Fenwick (1856–1938), his grandson, who oversaw the sales of the Phillipps collection over several decades. We know that Fenwick examined MS D2 in 1891 as his initials are found in the upper left corner of the verso of the back flyleaf: “T.FF 1891.” Within a few years of this inscription, the manuscript was sold by Fenwick at a Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge sale in 1895, during which it seems to have been purchased by Harold Baillie-Weaver (1860–1926), a British barrister and a book collector. Only three years later, in March 1898, the manuscript was purchased by Bernard Quaritch (1819–1899) during the sale of the collection of Baillie-Weaver by Christie, Manson & Woods. Bernard Quaritch was both a book collector and a bookseller, also based in London. In the late nineteenth-century, Quaritch had become one of the biggest traders in antiquarian books and manuscripts in the world. After his death, his bookselling business was continued by his son, Bernard Alfred Quaritch (1871–1913), and the company he founded still survives today as Bernard Quaritch Ltd, owned by John Koh.

MS D2 later appears in two of Quaritch’s sale catalogs, first immediately after its purchase in 1898 (Catalog no. 180, item no. 40) and then in 1902 (Catalog no. 211, item no. 153). The manuscript seems to have been purchased in 1902 by Sir Thomas Gibson-Carmichael (1859–1926), only to be sold a year later in a Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge sale of his collection. Gibson-Carmichael was a Scottish politician who held governorships in the British Empire. Since the manuscript reappears in a sale catalog of Quaritch in 1905, we can only assume that the younger Quaritch purchased the manuscript back during the 1903 Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge sale. However, only two years later, in 1907, MS D2 is again listed by Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge and this time it is sold to another bookseller, Francis Edwards Ltd, who listed the manuscript in their catalog in 1909. Established in 1855, also in London, Francis Edwards is another bookseller who continues to operate today.

The history of this fifteenth-century manuscript is a testament to the lively book trade business centered around London in the nineteenth century. After changing several hands, appearing in at least ten sale catalogs and briefly entering collections of famous British collectors in less than a century, the ownership trail of MS D2 goes cold for some twenty years following its appearance in the 1909 Francis Edwards catalog. We do not know whether the manuscript was sold at that time, and if it was to whom. The ongoing “Cultural Values and the International Trade in Medieval European Manuscripts, c. 1900-1945” project led by Laura Cleaver might provide us further clues in the future as to the whereabouts of the manuscript in the early decades of the twentieth century. About two decades later, in 1930, MS D2 is listed for sale by E. P. Goldschmidt & Co., which was founded by E. P. Goldschmidt (1887–1954), a scholar and a bookseller, also based in London. Whether the manuscript was sold in 1930 is also unclear. It is listed again by E. P. Goldschmidt & Co. in 1955, just after Goldschmidt’s death and it is possible that it remained in the inventory of the bookseller for twenty-five years when it was purchased in 1956 by the University of Kansas. Since then, for the past 65 years MS D2 has had its longest stay in its recent history in the same collection. You can track the history of MS D2 yourselves, examine the open access records of different sales and catalogs, and contribute to the history of the manuscript through the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from E. P. Goldschmidt & Co. in May 1956 and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

For the texts in this manuscript, see:

-

- Martial. Epigrams. Edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. 3 vols. Loeb Classical Library 94, 95, 480. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. [KU Libraries]

- Pliny the Younger. Letters. Translated by Betty Radice. 2 vols. Loeb Classical Library 55, 59. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969. [KU Libraries]

For introduction to provenance research, see:

-

- David Pearson. Provenance Research in Book History: A Handbook. New and revised edition. 1994. London: The Bodleian Library, 2019. [KU Libraries]

- Peter Kidd, Medieval Manuscripts Provenance.

- Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.