Ringle Conservation Internship: Hannah Scott Studio Collection

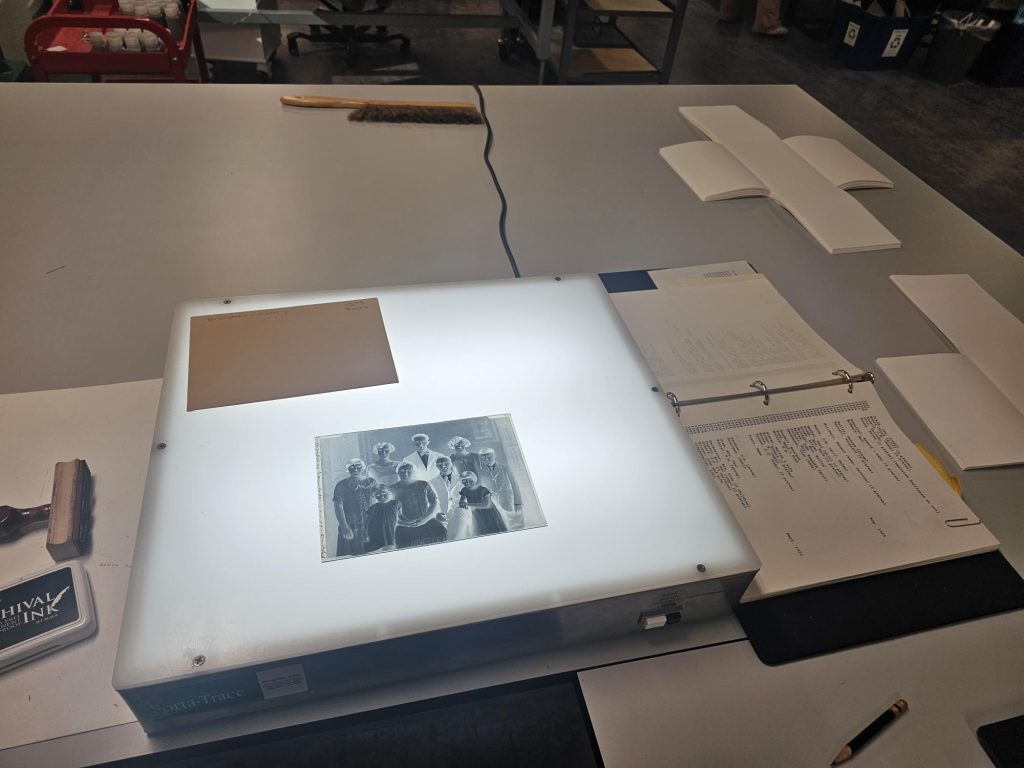

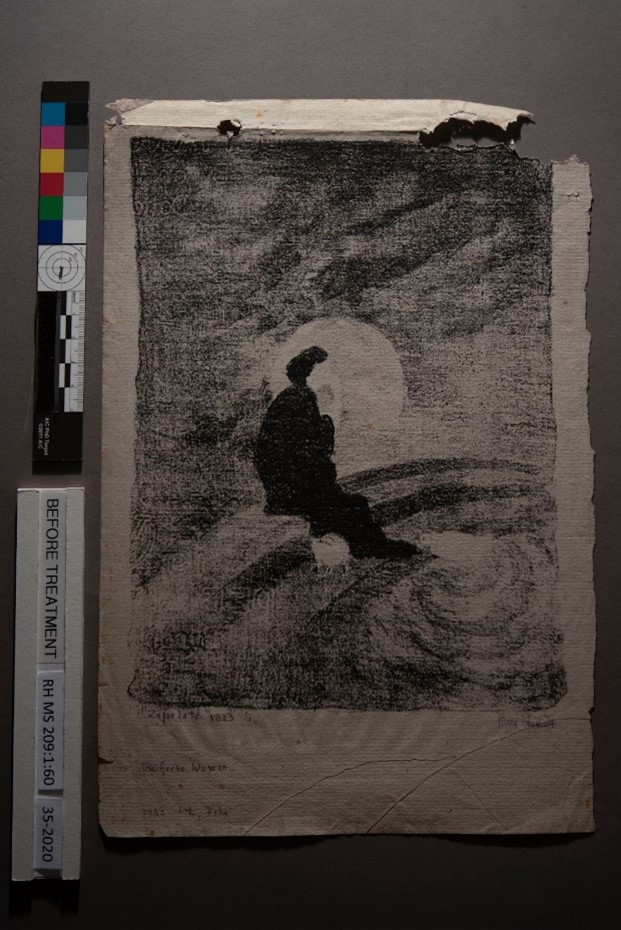

August 6th, 2024Having taken over the Ringle Conservation Internship from my predecessor and colleague Brendan Williams-Childs for the processing of the Hannah Scott photography collection, I have continued the necessary tasks and procedures to appropriately rehouse, organize, clean, and inventory thousands of glass plate negatives (3,821 to be exact) that comprise a mere fraction of the entire collection. These inventorying and rehousing procedures are much the same as other archival projects completed by interns and professionals in the field. Maintaining careful records and attention to detail are of paramount importance. The basic steps involve removing the old housing (acidic envelopes), notating the identifying information of each individual plate in a spreadsheet and on the new acid-free, four-flap enclosures, removing dust with a soft brush, and finally placing the completed rehoused plate into a new box. Such processes have been discussed, in detail, in many archival projects across repository institutions.

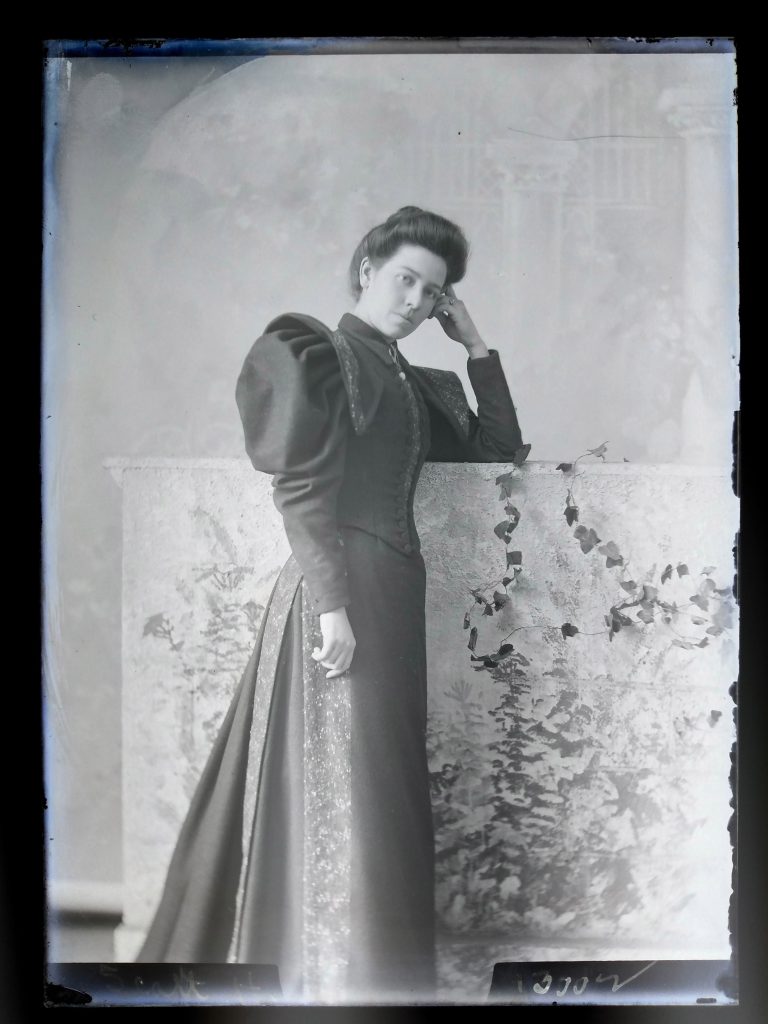

Rather than repeat the processing steps discussed by my predecessors, I examine the potential research opportunities and significance this collection embodies. Not only is this collection invaluable for genealogical research (Hannah’s meticulous record keeping make this collection a researchers dream) but also for women and gender studies. The uniqueness and increasing fascination I have discovered in this collection and internship lies with the photographic abilities and entrepreneurial spunk displayed by Hannah Scott as an independent businesswoman in the early 20th century. Her distinct ability to photographically capture lively images of young children combined with her apparent business acumen make her a noteworthy example of Kansan and female ingenuity.

It seems that Hannah’s work process encouraged taking multiple photos with different backgrounds, props, and poses. In several of the plates, elements of the studio were inadvertently captured including figures not part of the carefully crafted tableaux. Particularly with the young children, there seems to be a degree of collaboration with the mothers who attempt to gain the child’s attention and happy expression. Hannah seems to have encouraged these interactions to achieve the desired image results. Hannah’s skill with timing and attention to detail while coordinating with the parent was one of her greatest strengths as an artist-businesswoman, achieving crystal-clear, natural images. Many of her other images are conventionally posed and formatted to express family relations and pristine pseudo-intellectualism (many older children and adults stiffly hold/read books, magazines, and diplomas). Like today, these artistic choices responded to the desires of the clients and the photographic conventions witnessed in the popular media.

Later images start to appear more relaxed and natural overall. Perhaps this indicates a shift in how people understood photography not as just a formal once or twice in a lifetime event but a more commonplace fun activity in which they felt freer to express their personality with a technology they had become familiar with as children. It should also be noted that there are significantly more women who are commissioning portraits than men. Images of children make up most of the portrait subject matter but the plates and register books indicate a “Mrs.” John Smith, more often than the given name of the child or male name. The sheer number of plates and named clients attests to Hannah’s popularity as a portrait photographer.

Hannah Scott was born in Canada in 1872 to Scottish immigrants who later settled in Kansas. She was the fifth of seven children and the only girl. Hannah chose her career path through the inspiration of an article in the Ladies Home Journal by Edward Bok. This article advised that ladies with an artistic inclination were well suited for studio photography as this was deemed suitable work for women at the time. With the approval and support of her family, Hannah pursued a photographic career. With unflagging initiative and energy Hannah apprenticed and advertised with the local photo studio, the Stone Front Studio, owned and operated by Allen Brown. Eventually Hannah bought out Allen Brown to open her own studio, “The Hannah Scott Studio,” later “Scott Photography Studio.” Starting out on her own in 1898, she rented studio space on the second floor of a local commercial building in downtown Independence KS. In 1916 she purchased a lot at 111 South 8th street in Independence and commissioned a new studio building. The titles for this property were in Hannah’s name and over the years three mortgages were taken out and quickly paid off indicating Hannah’s autonomy and success as a businesswoman. Later she hired her younger brother Hugh to work in the development process and as a junior partner, but Hannah maintained primary control of the business until her death.

More research is needed to fully examine Hannah Scott’s life and work. As an important example of women in business and industry, Scott’s life can expand current perceptions of women’s work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Previous scholars have mentioned the Independence Historical Society might have more information about Hannah and her family in the local archives. Once fully indexed with a published online finding aid, this collection will prove invaluable for genealogical research for southeastern Kansas.

Hannah Johnson

Ringle Conservation Intern, 2023-2024