Conservation Treatment of a Korean Buddhist Sutra, Dae Bangwangbul Hwaeomgyeong (The Sutra of Garland Flower of Great Square and Broad World of Buddha)

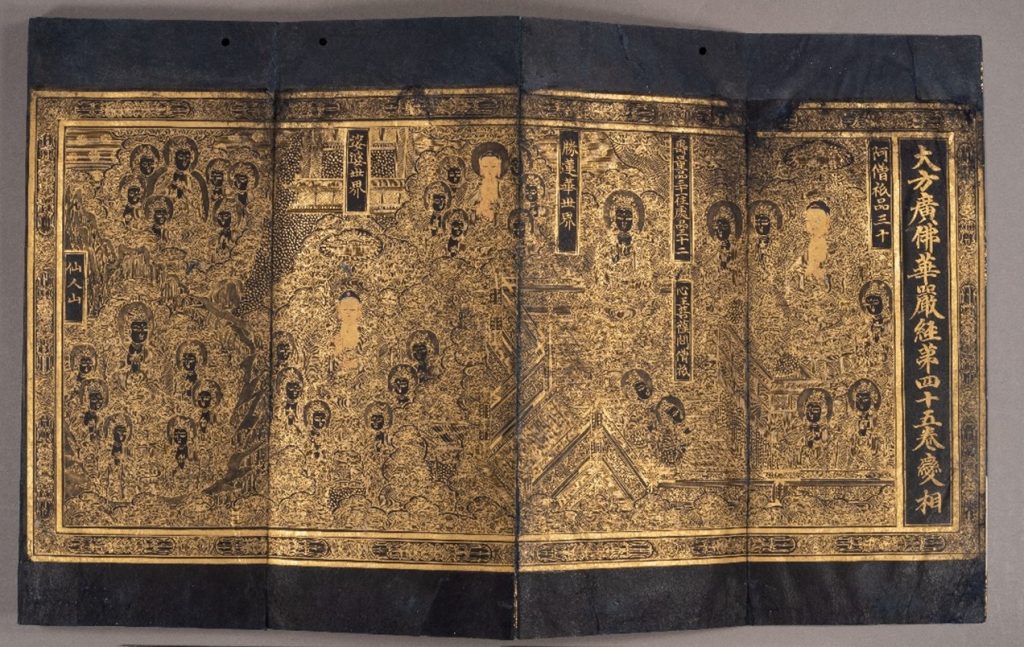

March 8th, 2022The Kenneth Spencer Research Library holds a rare 14th century Korean Buddhist sutra (MS D23) titled, Dae Bangwangbul Hwaeomgyeong (The Sutra of Garland Flower of Great Square and Broad World of Buddha). The sutra is the 45th volume of the eightieth version of the Avatamsaka Sutra translated by Siksananda between 695 and 699 in the Tang dynasty (Eung-Chon Choi, 2003). It is mounted in accordion book format, a practice commonly seen in China, Japan, and Korea (Hsin-Chen Tsai, 2017).

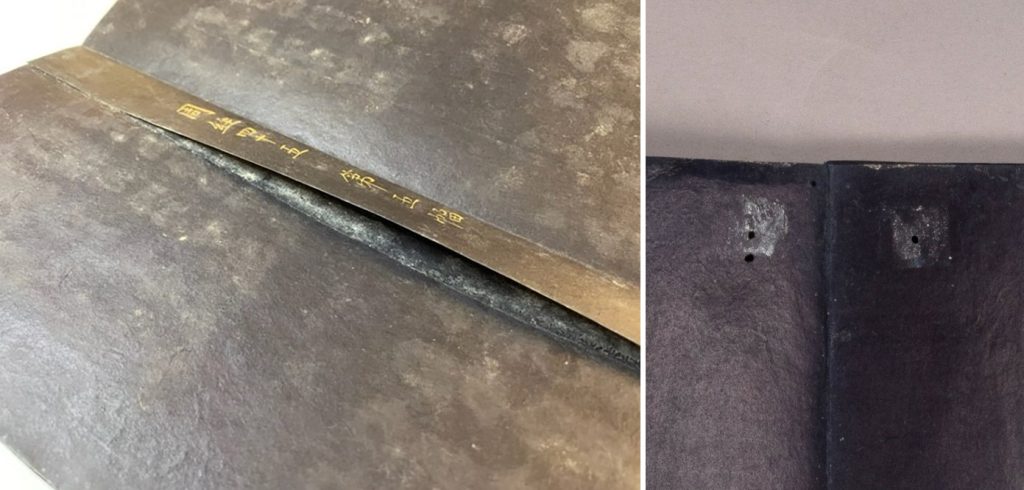

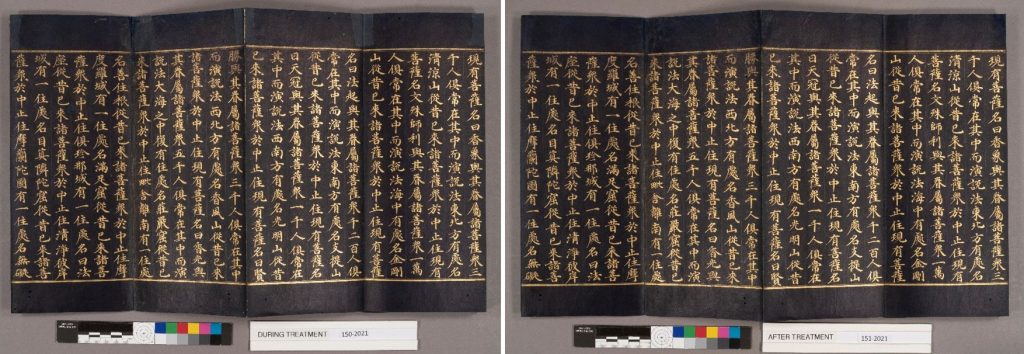

The sutra’s structure consists of papers with a width of 101 cm and height of 26.7 cm that are joined by one seam every nine pages with a starch-based adhesive[1]. The sutra has sixty-one pages of text comprising three chapters, and four pages on which is painted the frontispiece. The calligraphy and frontispiece are hand-painted in a metallic media, likely gold, where gold pigment is typically mixed with animal glue as the binding media (Hsin-Chem Tsai, 2017). The outer edges of the text block are also decorated in gold. The heads, chest, and hands of the three Buddhas in the frontispiece are further enhanced with cream, red, blue, and black opaque paint. The verso of the sutra is blank except for inscriptions along the seam of each join labeling each section.

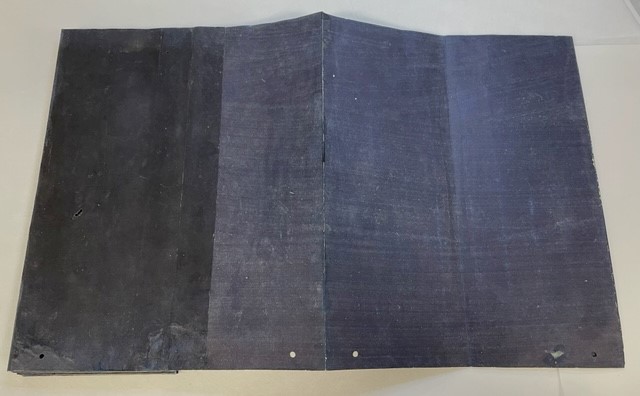

There are four different papers observed throughout the sutra. The text block of the sutra is a double layer of dark blue dyed paper, likely indigo, that is highly burnished. The paper used on the verso of the frontispiece, back cover, and adjacent pages is a different laminated indigo paper. It is not burnished, and the indigo has prominent brush strokes (see Image 2). The paper cover has a white paper core consisting of a few sheets laminated together and is covered with a thin, blue paper. The front cover is decorated with flakes of gold leaf while the back blue paper cover is blank. Fiber identification characterized the furnish (fiber content) of these papers as a paper mulberry or a paper mulberry mixture with either mitsumata or gampi. These fibers are consistent with the known furnish of papers from this period and region.

According to Goryeo dynasty: Korea’s age of enlightenment, 918-1392, the following volumes from this set of Avatamsaka Sutra are extant and share the same style of calligraphy, treatment of the frontispiece, and cover design: Vol. 1 (private collection in Japan), Vol. 4 (Tokugawa Art Museum), Vols. 35 and 36 (Yamato Bunkakan), Vol. 42 (Tsaian-ji, Kobe), and Vol. 78 (The Cleveland Museum of Art).

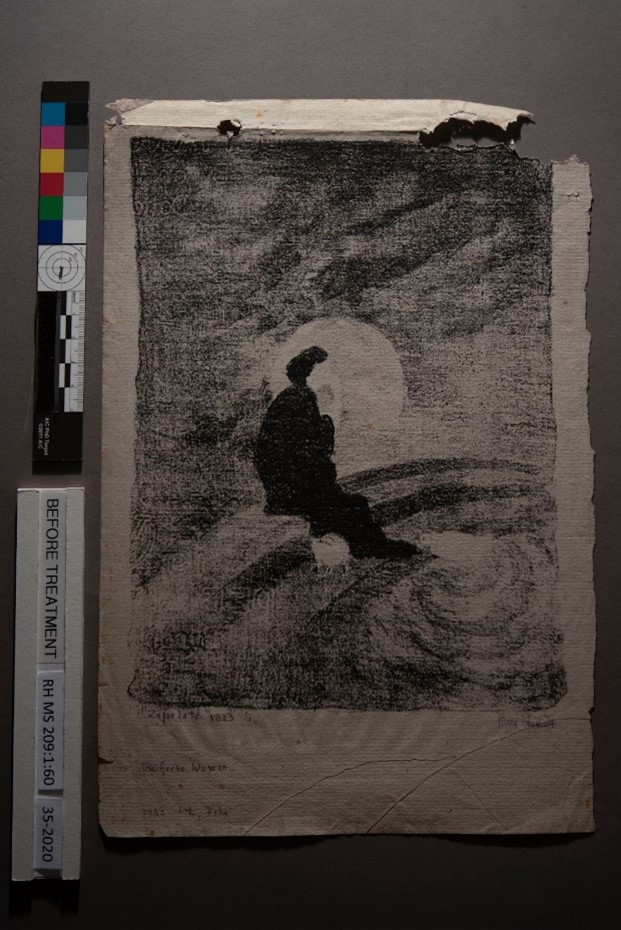

The sutra had several structural issues (weak folds, insect damage, old mends that were detaching) and was a priority for examination and treatment to stabilize it for future use. With great thanks to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and its support of a Collaborative Conservation Initiative at KU, there was allocated funding to host a visiting conservator to complete a special week-long project during the grant period. We reached out to Minah Song, a conservator in private practice in the Washington D.C. area, to advise on the development of a treatment plan for this rare object. Read more about Minah’s entire Visiting Conservator Project in the blog post written by Special Collections Conservator, Angela Andres.

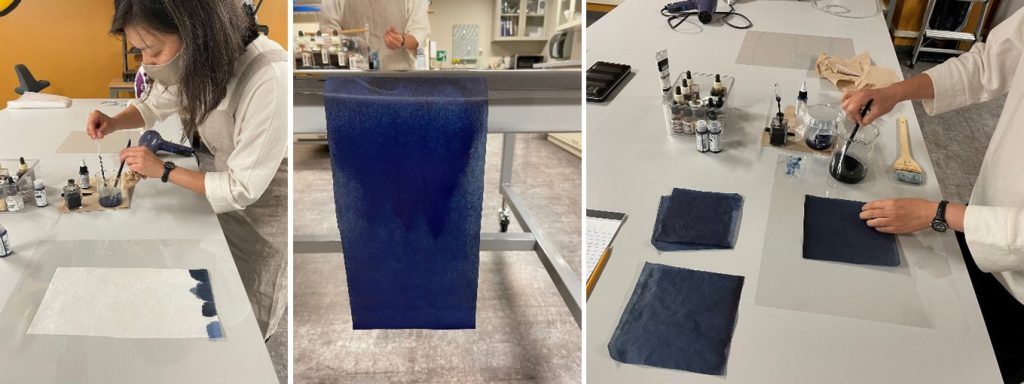

After the sutra was examined and the condition issues prioritized, we shared our observations and treatment plan with Elspeth Healey, special collections librarian, who authorized the treatment. Our plan included addressing all necessary mending needs first. If we could tone a good matching paper, then we would also address the most visually distracting mends and overlays to reintegrate the paper margins of the sutra. We toned handmade Korean paper (hanji) using High Flow Golden acrylic paint (indigo/anthraquinone) and Dr. Ph. Martin’s Synchromatic Transparent watercolor (black) diluted with deionized water to mix various blue tones and achieve a good match with the sutra’s burnished indigo paper. The mixture was brush-applied to the hanji and the paper was hung to dry completely.

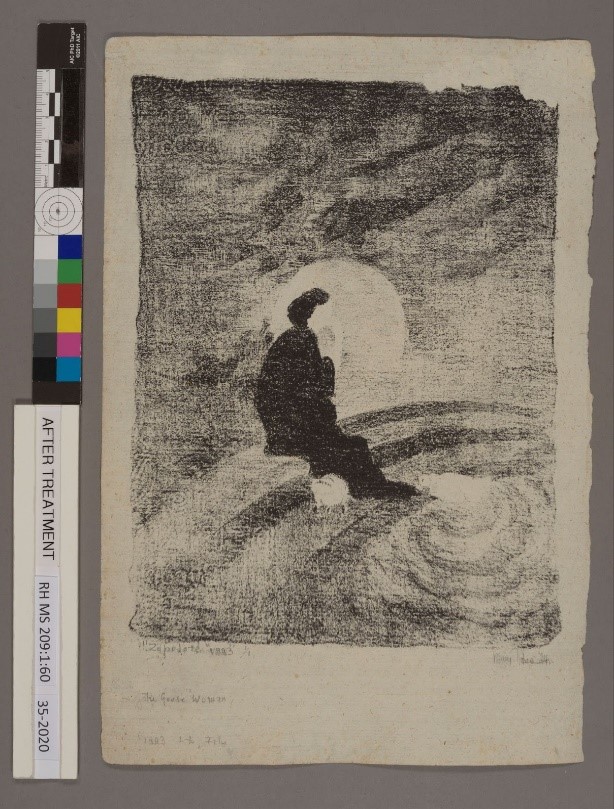

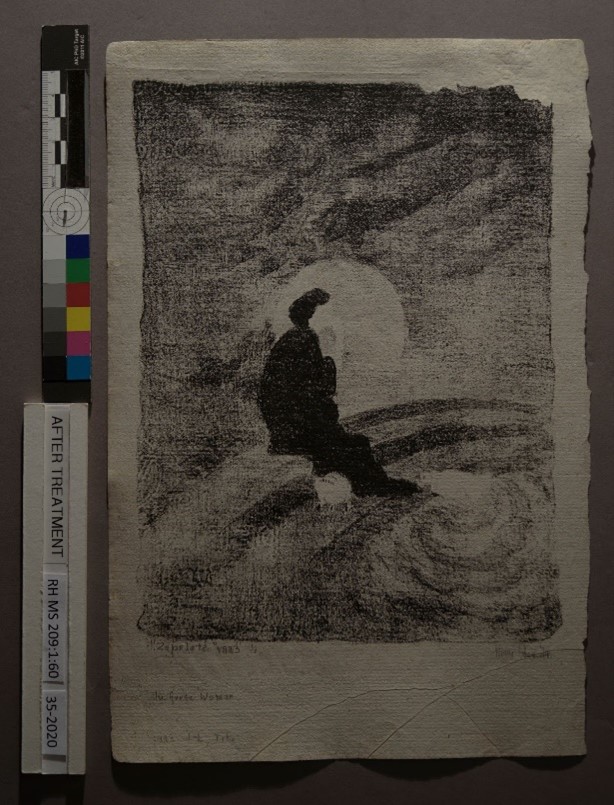

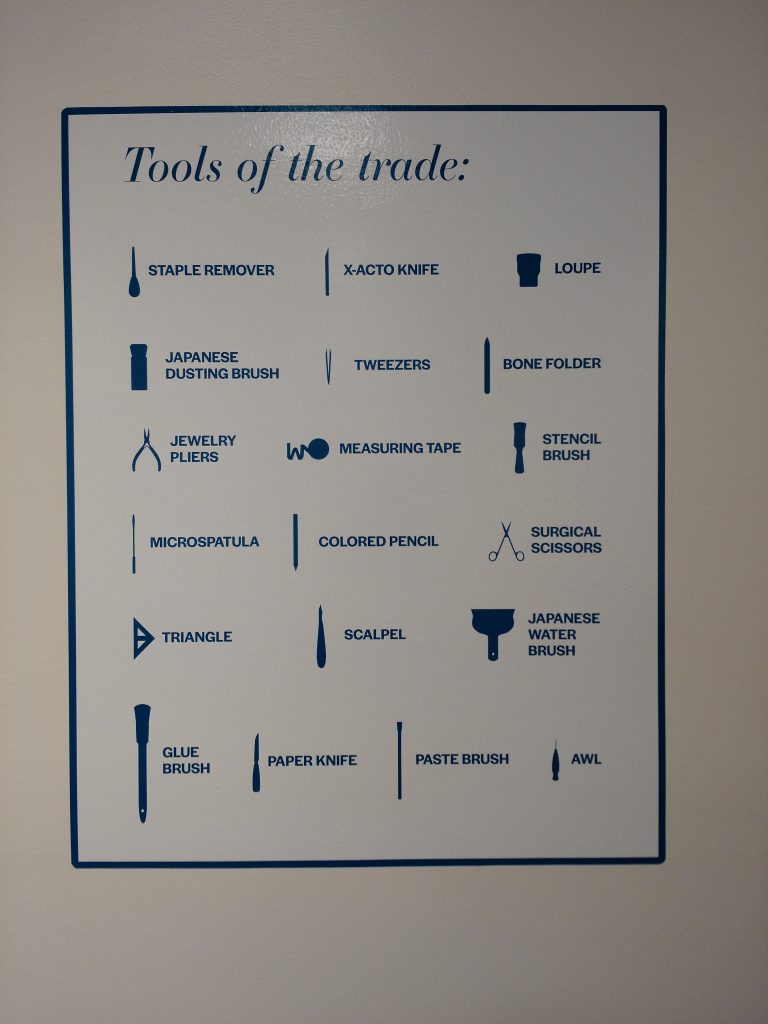

Once the paper was toned, we removed old mends across worm holes that were loose and detaching. We used the new mending paper to reinforce weak fold creases and replace old mends, as needed, and reattached the seams that were coming loose. The treatment overall was kept as minimal as possible with the primary goal of stabilization so that the sutra could be safely handled. Once the new mends and infills were attached with wheat starch paste, some were locally inpainted with Schminke watercolors to match the sutra’s paper tone more closely.

The conservation treatment of the sutra is now complete. The new mends have better visual integration with the object and allow for the sutra to be safely handled. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to Minah Song for her guidance and expertise on this important project. We would also like to thank Dr. Brian Atkinson, Assistant Professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Curator of the Division of Paleobotany at the Biodiversity Institute for the use of his microscope to complete fiber identification. Finally, we would like to thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for enabling this collaboration.

[1] The final section is only five pages long, including the cover, and is 55.8 cm wide. Adhesive was tested with an iodine indicator. The adhesive is likely wheat or rice starch paste.

REFERENCES

Avatamsaka Sutra No. 78. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Collection Entry. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1994.25.

Baker, Whitney. June 18, 2003. Condition Examination. The Kenneth Spencer Research Library. The University of Kansas Libraries.

Choi, Eung-Chon, and Kumja Paik Kim. 2003. Goryeo dynasty: Korea’s age of enlightenment, 918-1392 ; [in conjunction with the Exhibition Goryeo Dynasty: Korea’s Age of Enlightenment, 918-1392, which was organized by the Asian Art Museum – Chong-Moon Lee Center for Asian Art and Culture, San Francisco, October 18, 2003 through January 11, 2004]. San Francisco, Calif: Asian Art Museum: 126-7.

Tsai, Hsin-Chen, and Tanya Uyeda. 2017. “Line Up, Back to Back: Restoration of a Korean Buddhist Sutra in Accordion Book Format.” Book and Paper Group Annual 36: 75–83.