Manuscript of the Month: Putting the Spotlight on the Once Influential Translation ‘On the Life of a Tyrant’ by Leonardo Bruni

February 25th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

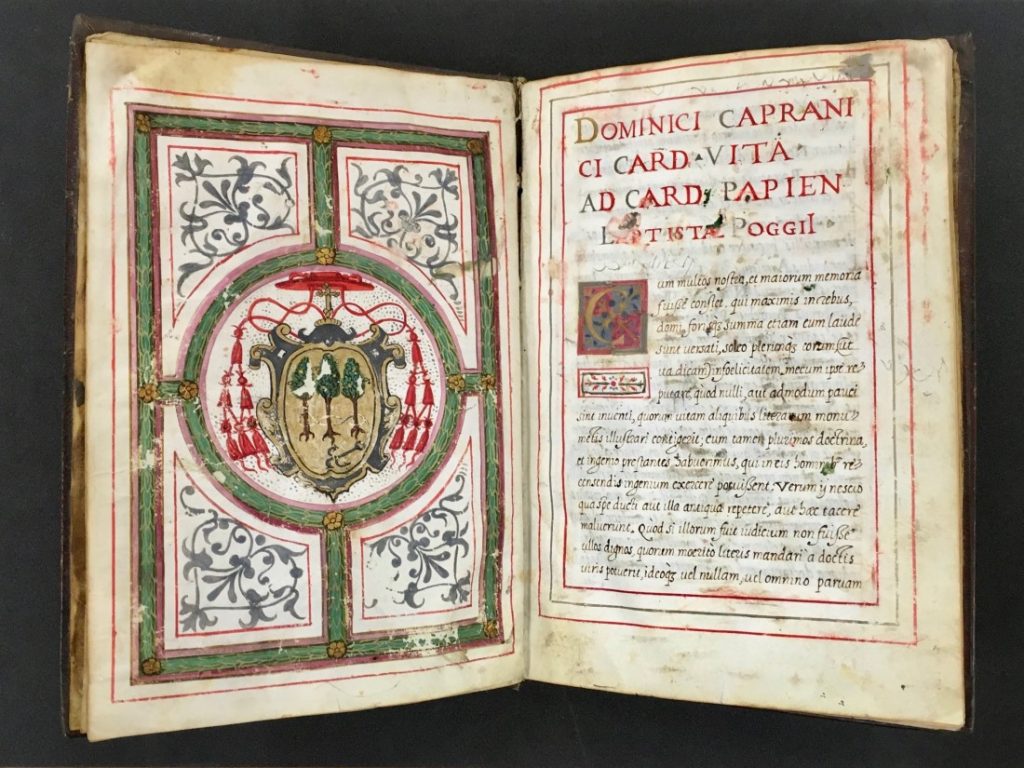

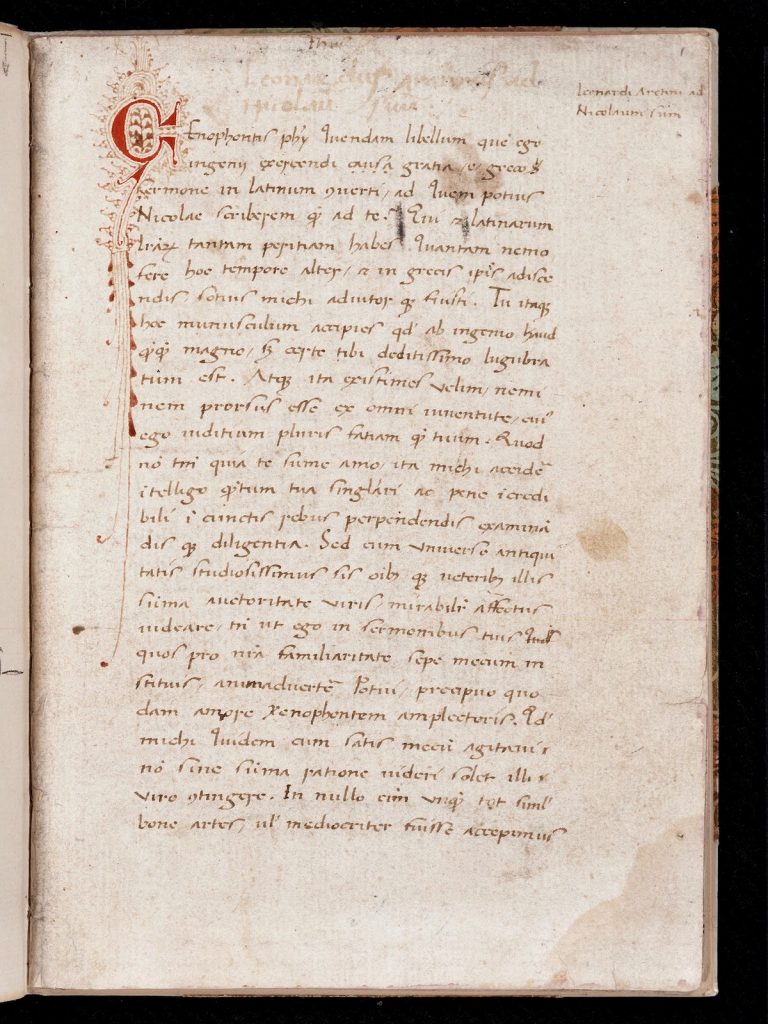

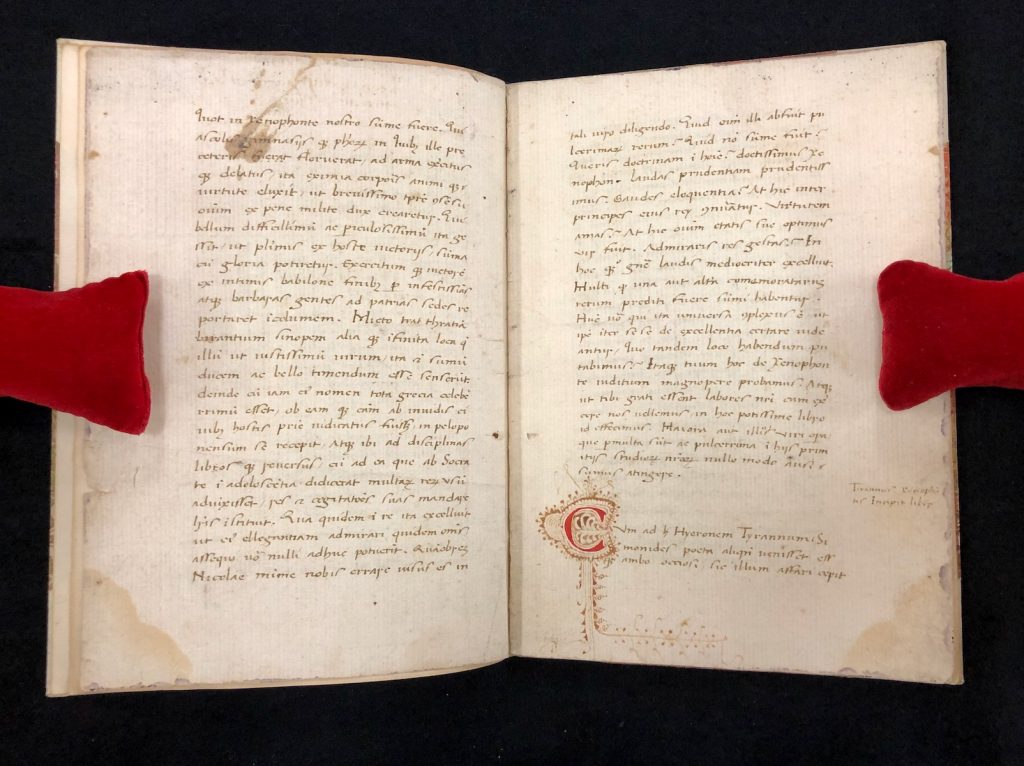

According to our records, it has been some years since any researcher looked at Kenneth Spencer Research Library, MS C68, a paper manuscript of 16 leaves arranged in a single quire. MS C68 contains a single text, a translation into Latin of a work in Greek called the Hiero by Xenophon. Xenophon (c. 431 BCE–354 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian and the Hiero is significant as being his first work to be translated into Latin as far as we know. This translation into Latin by Leonardo Bruni was completed at the very beginning of the fifteenth century, in May 1403, under the title of the De vita tirannica [‘On the Life of a Tyrant’]. Leonardo Bruni (1370-1444), a renowned Italian humanist, translated several classical works from Greek into Latin including those of Aristotle and Plato as well as other works by Xenophon.

Xenophon’s Hiero is a short piece, set as a dialogue between Hiero I, tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BCE, and Simonides of Ceos (c. 556–468 BCE), a lyric poet. They discuss how the lives of a tyrant and an ordinary citizen differ with regard to joys and sorrows. Framed as a conversation between a ruler and a wise man, the Hiero is left somewhat open-ended, with Hiero arguing that a tyrant has far fewer pleasures and many more and much greater pains than an ordinary person and Simonides offering advice on how to improve Hiero’s life by enriching himself with friends and employing deeds of kindness.

Knowledge of the Greek language was very rare in the Latin West in the later Middle Ages. Leonardo Bruni learned Greek from Manuel Chrysoloras (c. 1355–1415), who was a diplomat of the Byzantine Empire in Italy. In 1396, Chrysoloras was invited to come to Florence as a professor of Greek by Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), the Chancellor of Florence, who was also a renowned humanist scholar and a book collector. Salutati was also the patron of Bruni, who succeeded Salutati as the Chancellor of Florence. In his preface to the translation, Bruni refers to the De vita tirannica as a libellus–a little book or a booklet–and dedicates it to Niccolò Niccoli, who he thinks would “embrace Xenophon with a particular love.” Another Florentine and a friend of Bruni, Niccolò Niccoli (1365–1437) was also a protégée of Salutati and is credited for developing the Italian cursive script.

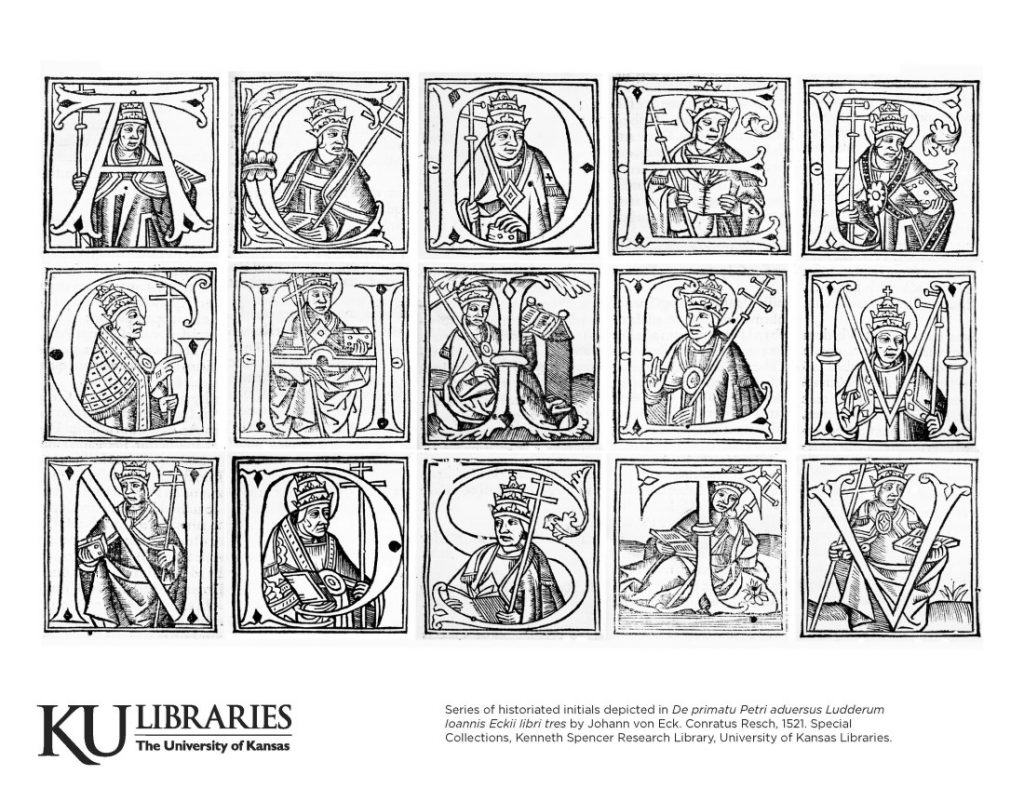

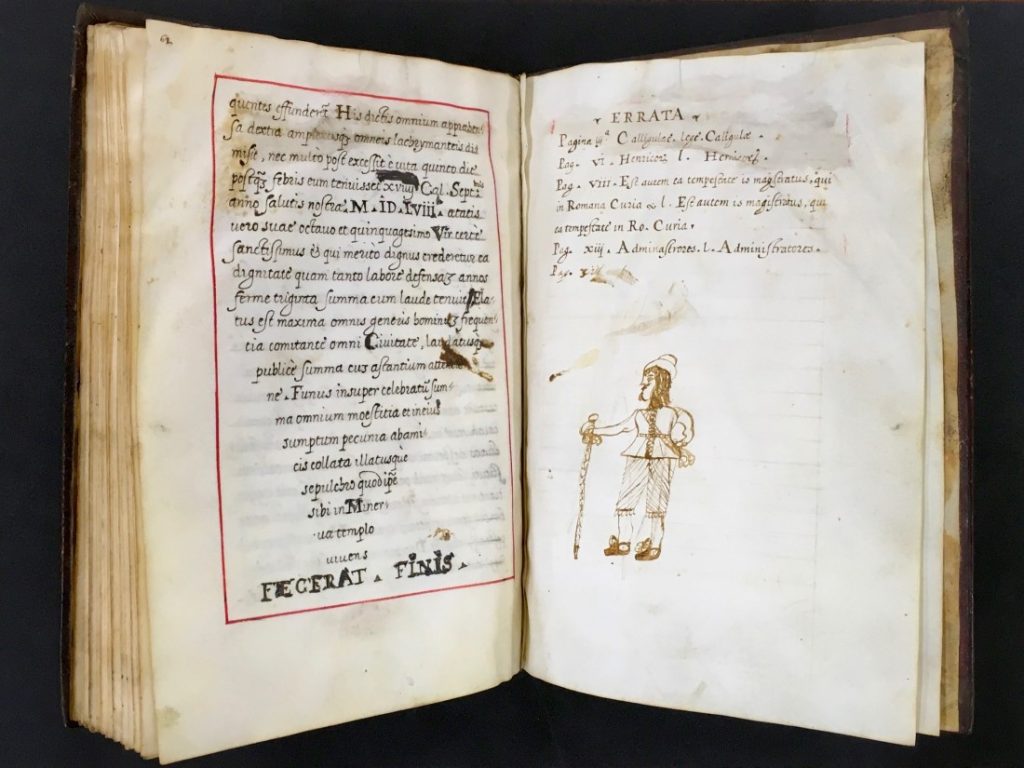

The lack of interest in MS C68 may be explained with what Brian Jeffrey Maxson calls a “small amount of scholarship” on the work in modern times. Even though Bruni’s De vita tirannica had made available to readers in Latin an otherwise inaccessible text in Greek and was very popular during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it has received little attention in modern scholarship. There is neither a modern edition nor a translation of the work into a modern language. Nor are there any comparative studies dealing with both the Greek and the Latin versions of the story. We know, for example, that Coluccio Salutati published a treatise titled the De tyranno [‘On the Tyrant’] in 1400 and the topic of good rulership was being discussed in his political and scholarly circles. Therefore, it can hardly be a coincidence that Bruni titles his translation the De vita tirannica instead of keeping the original, that is the tyrant’s name, Hiero. Another indicator that Bruni’s translation was read and circulated widely is that this short translation was published in print editions at least eight times within a span of thirty years between 1470s and the end of the century, and our MS C68 is one of estimated 200 manuscript witnesses of the translation that survive today.

Neither the origin nor the early history of MS C68 is known. However, the examination of script and the watermarks in the manuscript put the date of origin to somewhere in the first third of the fifteenth century. This means that MS C68 was probably copied during Bruni’s lifetime.

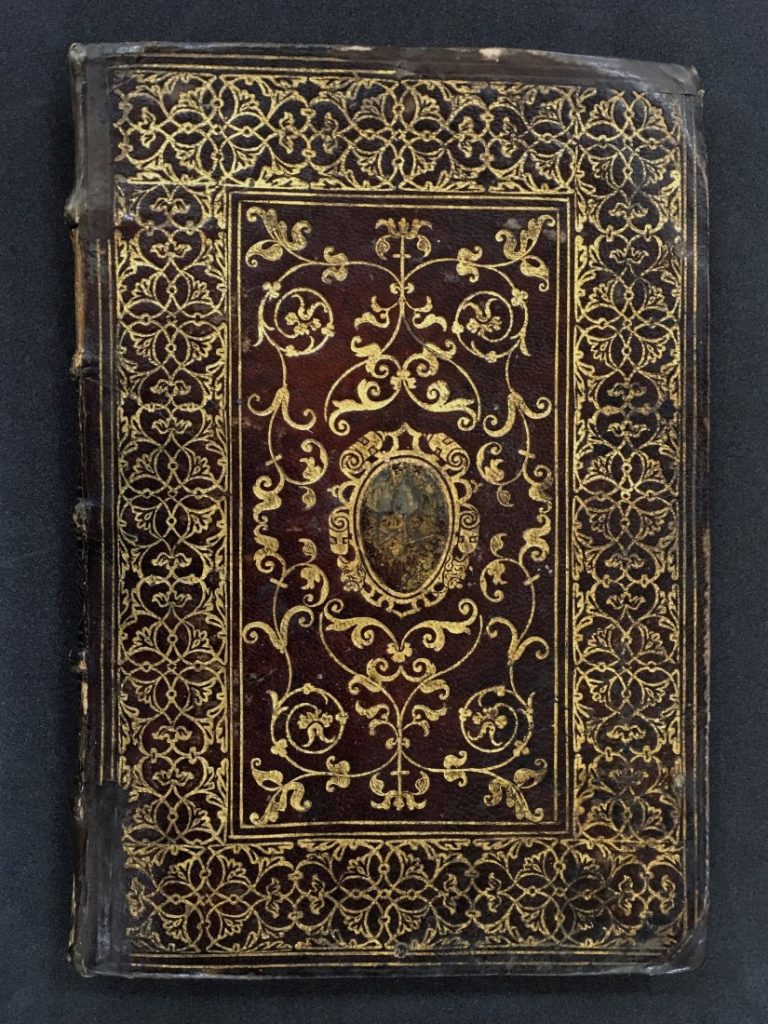

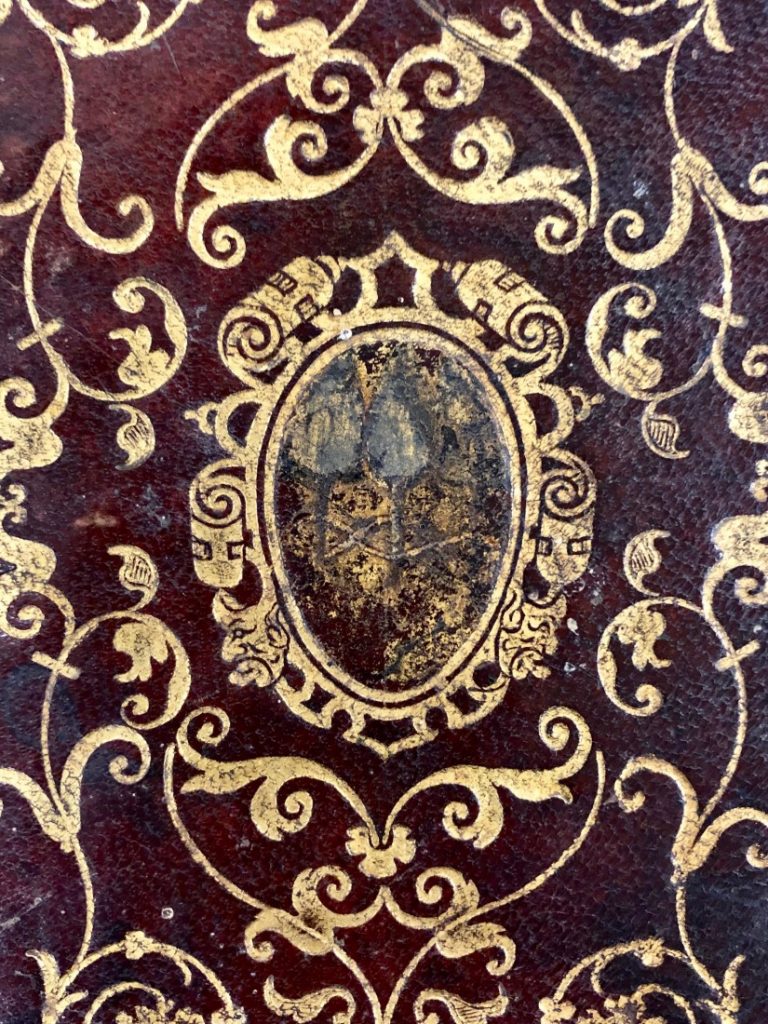

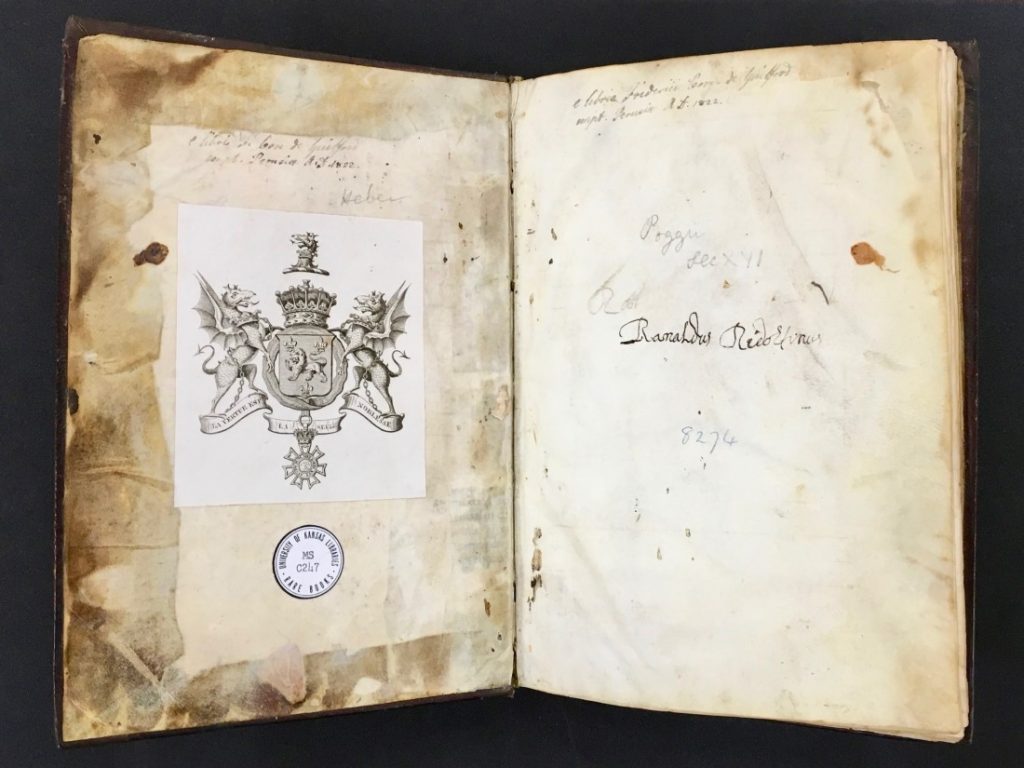

As it currently stands, MS C68 has a modern binding, perhaps from the nineteenth century, and carries the bookplate of Sigurd and Gudrun Wandel on the front pastedown. Sigurd Wandel (1875–1947) was a Danish painter, who later became the director of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, and Gudrun Wandel (1882–1976) was his first wife. At least two other books with the same bookplate from their collection in Denmark ended up in the United States and are now at the Penn Libraries.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Bernard M. Rosenthal Inc. in July 1960, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room.

- Read a translation from Greek into English of Xenophon’s Hiero on Perseus.

- Read more about translations from Greek into Latin in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries here: Paul Botley. Latin Translation in the Renaissance: The Theory and Practice of Leonardo Bruni, Giannozzo Manetti and Desiderius Erasmus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN: 978-0521837170

- Read more about the context in which Leonardo Bruni translated the Hiero here: Brian Jeffrey Maxson. “Kings and Tyrants: Leonardo Bruni’s Translation of Xenophon’s Hiero.” Renaissance Studies 42.2 (April 2010): 188–206. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-4658.2009.00619.x

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher