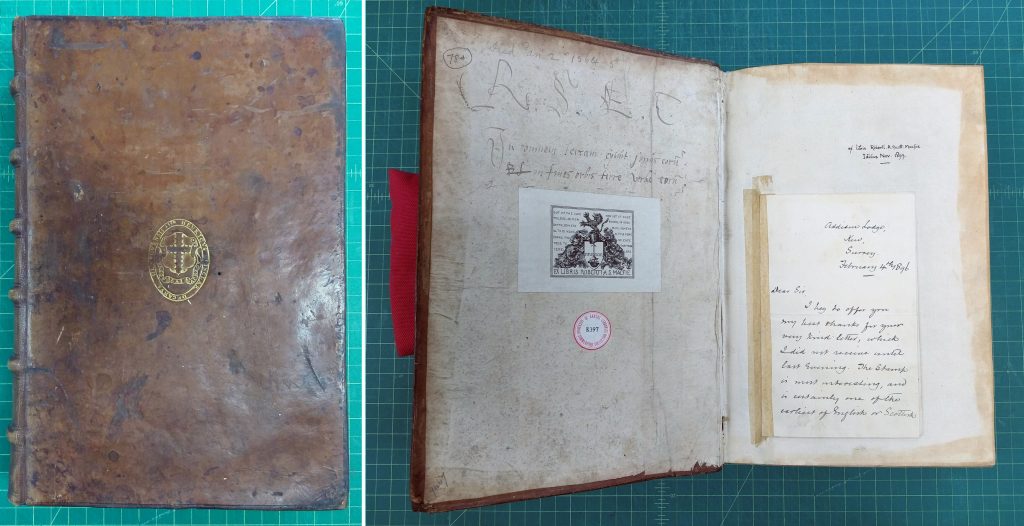

Last year, I wrote about my survey of part of the Summerfield Collection of Renaissance and Early Modern Books, and all of the lovely hidden treasures within that collection. One item that I identified during the survey as a candidate for future treatment is Summerfield E397, De statu religionis et reipublicae, Carolo Quinto Caesare, commentarii, by Johannes Sleidanus, published in 1555.

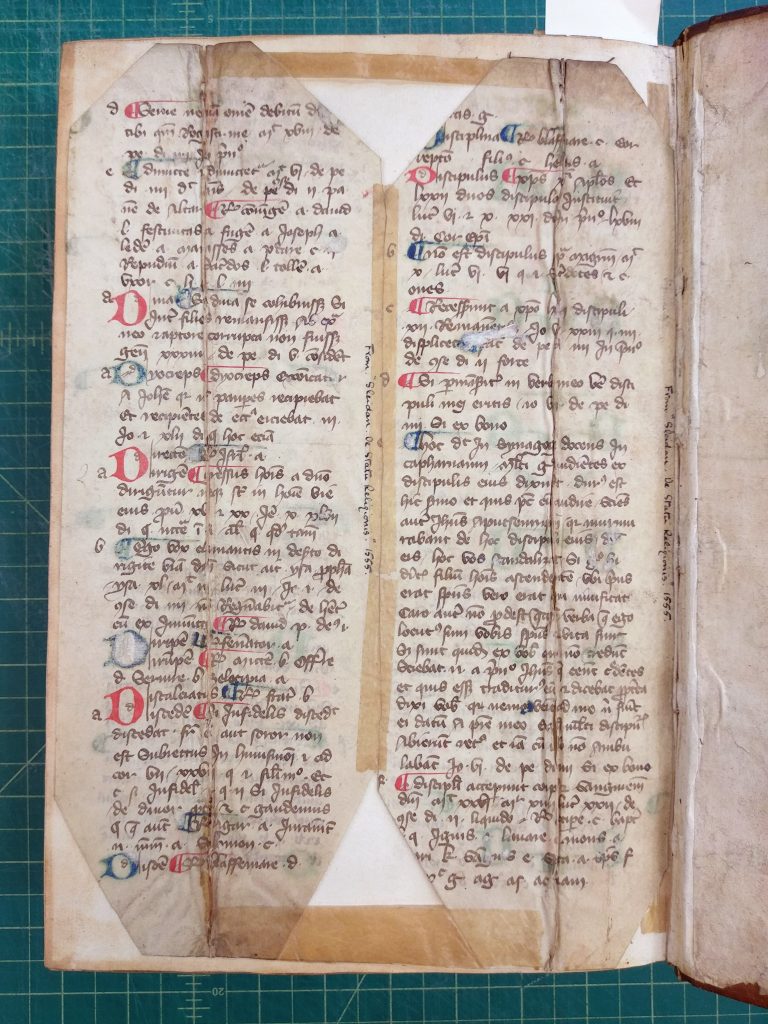

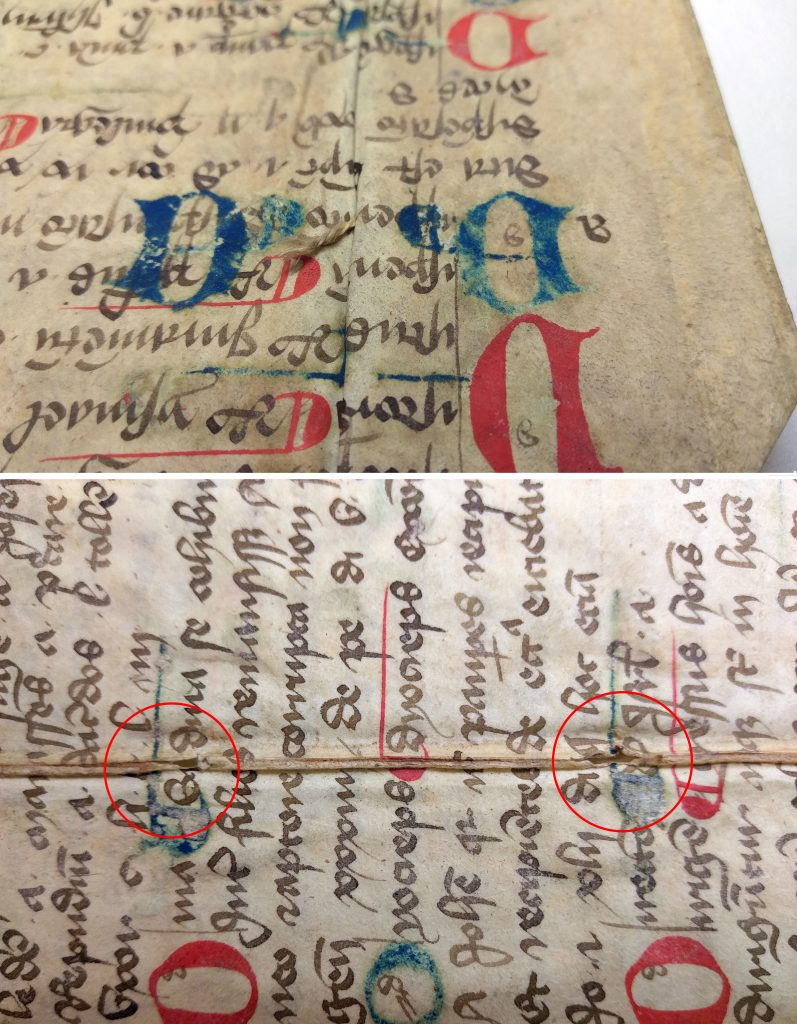

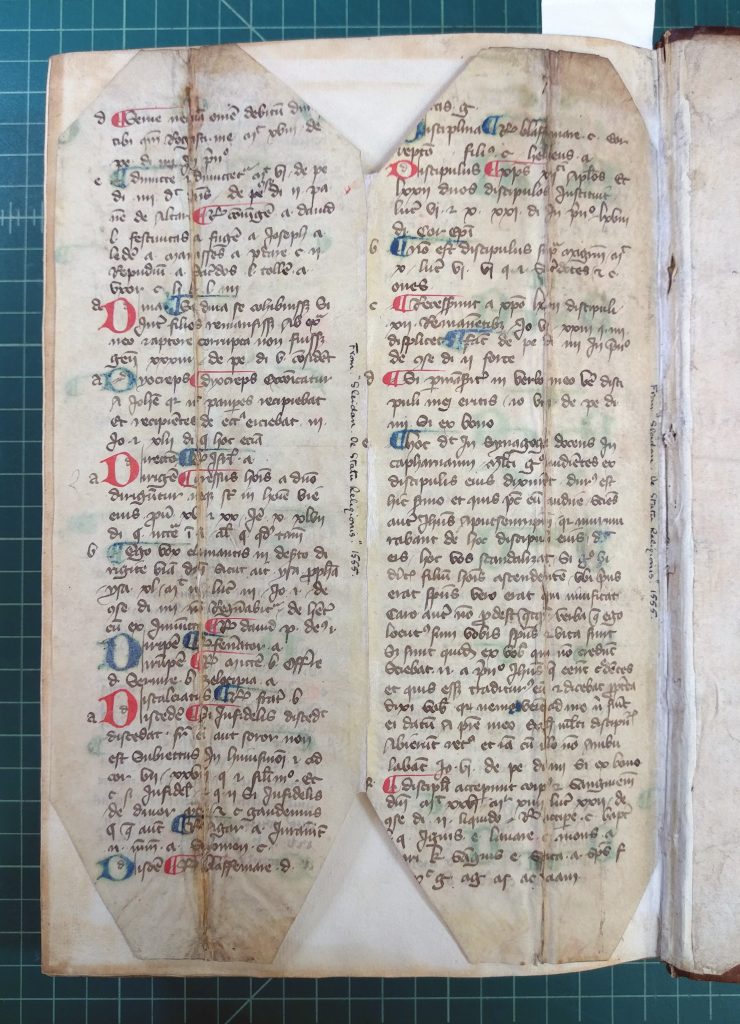

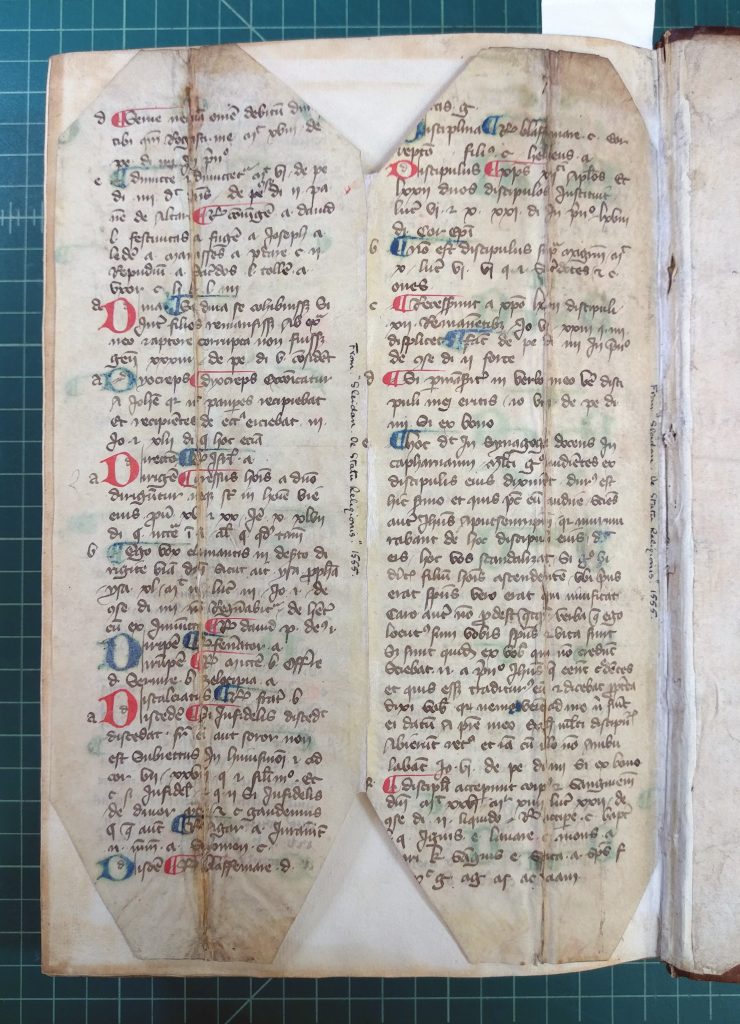

What caught my attention about this volume is the fragment of parchment manuscript that was taped inside the lower board. Actually, there are two fragments – halves of a leaf that long ago was cut apart and used to form flanges that were sewn onto either side of the text block and then adhered between the boards and pastedowns. At some later time, the book was repaired and the manuscript flanges were removed. Whoever removed them chose to retain them, piecing them back together with glassine tape and affixing them inside the back of the book.

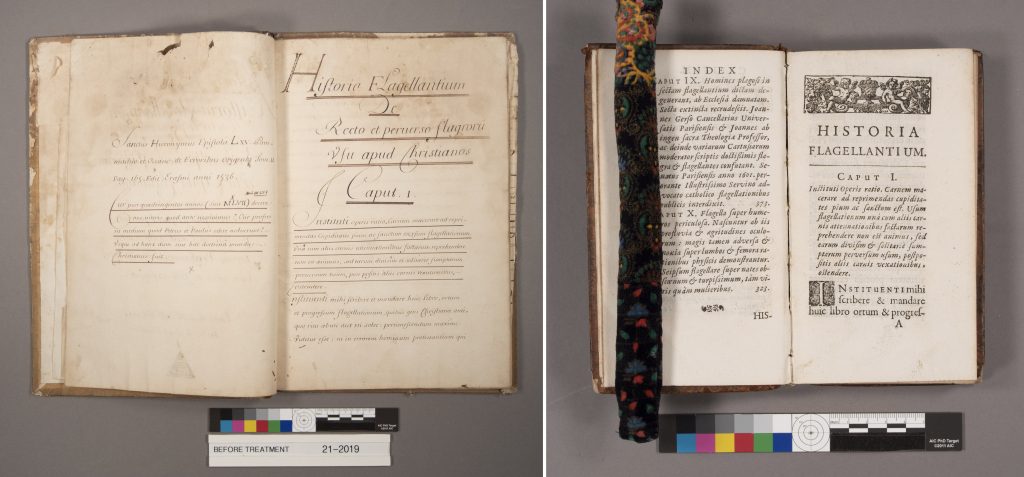

Manuscript fragments, previously used as binder’s waste,

taped into the back of Summerfield E397. Click image to enlarge.

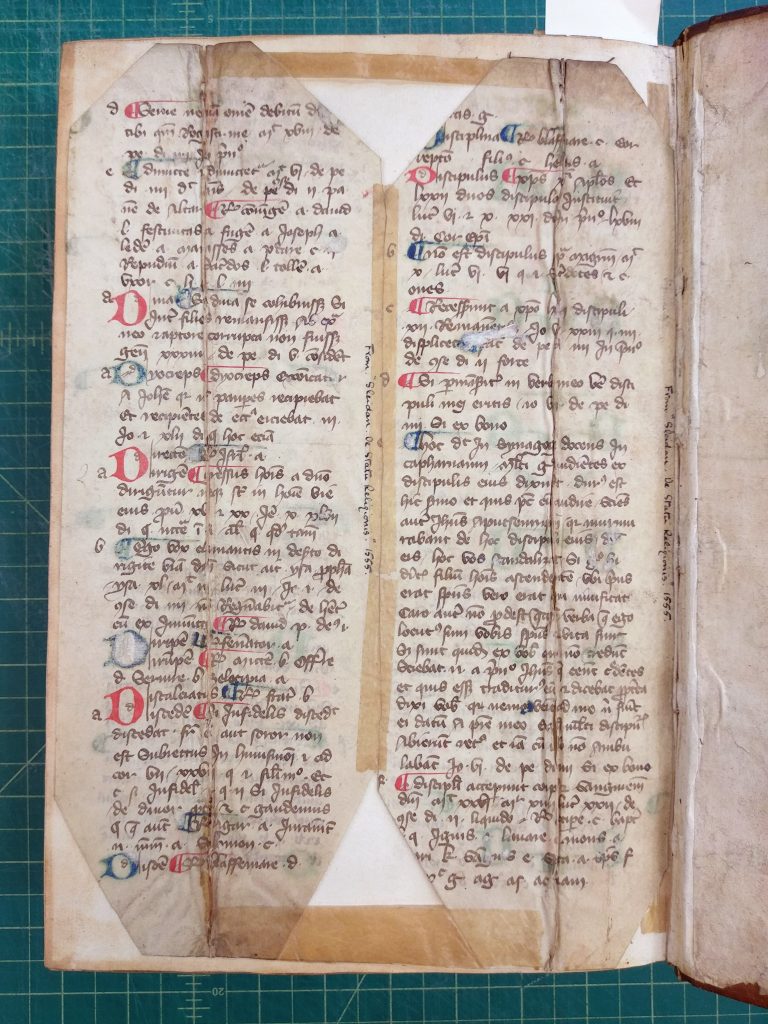

In the front of the volume are affixed two letters dated in February 1896 that a one-time owner of the volume – one Robert A. Scott Macfie – received from a William Y. Fletcher in response to an inquiry he had sent about the book (Fletcher’s name appears in a 1908 list of members of the Bibliographical Society of London). The second of these letters mentions that Fletcher had shown the book (which Macfie had lent him to examine) to “Mr. Scott and Mr. Warner, the Keeper and Assistant Keeper of MSS in the [British] Museum, and they consider [the fragments] to have belonged to an English or Scottish MS (most probably the former) of the 15th century.” How fascinating and fortunate that these records of the book’s life have survived with it.

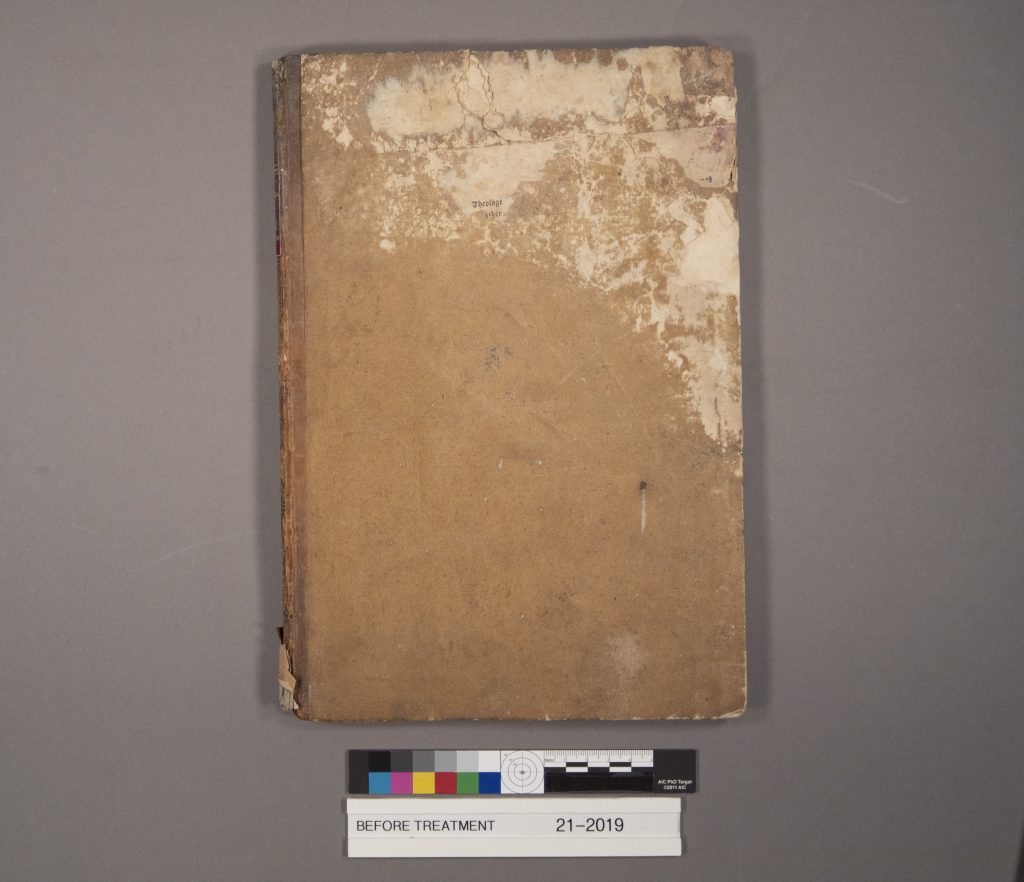

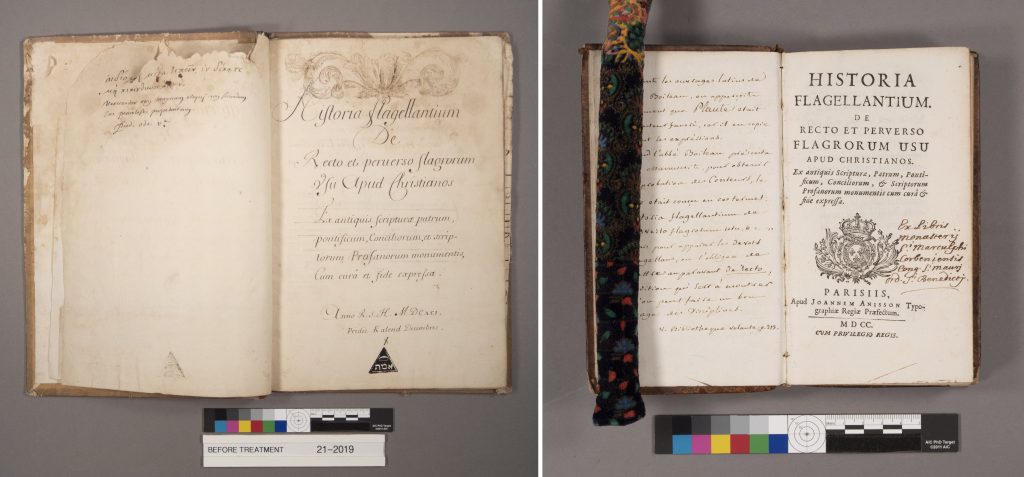

Left: Cover of Summerfield E397. Right: Fletcher’s letters to Macfie

taped onto front flyleaf. Click image to enlarge.

At the time that I surveyed this book, I consulted with the curator about how to approach the treatment and made a note to revisit it at a later date. I recently reviewed my queue of projects and this one presented itself. In my discussion with the curator, we had agreed to leave the letters as-is, but to remove the tape from the manuscript fragments, reunite them with wheat starch paste and Japanese tissue, and tip them back into the volume with the same. Their presence in the volume tells something of the book’s story, but we felt it would be beneficial to remove the brittle, discolored tape from the parchment.

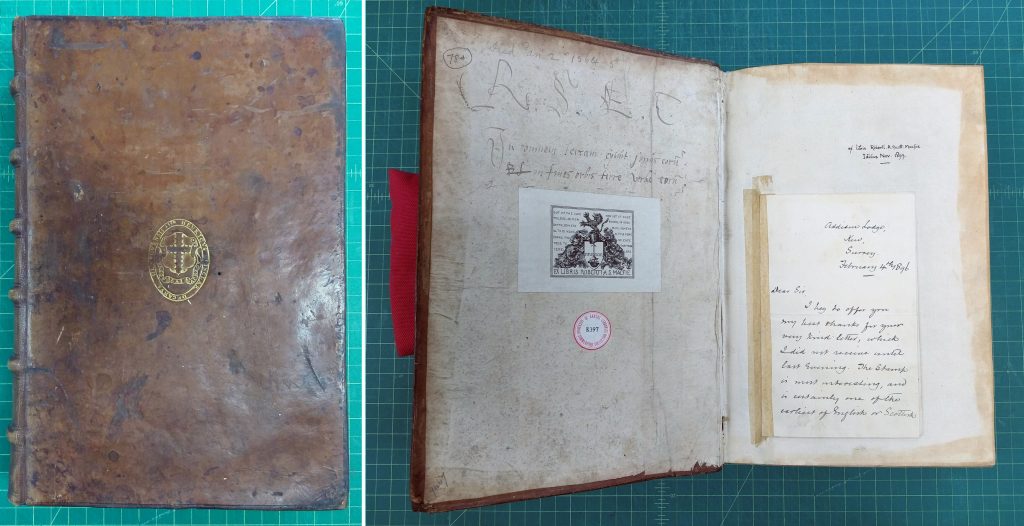

Visible threads (top) and sewing holes (bottom) indicating

these fragments had been used as binder’s waste.

Click image to enlarge.

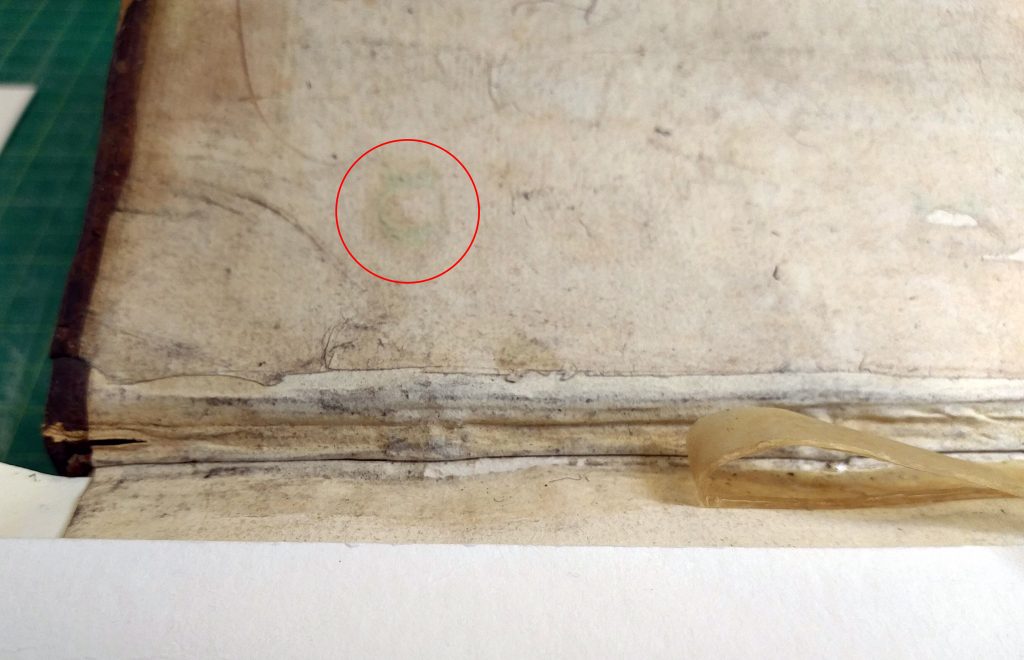

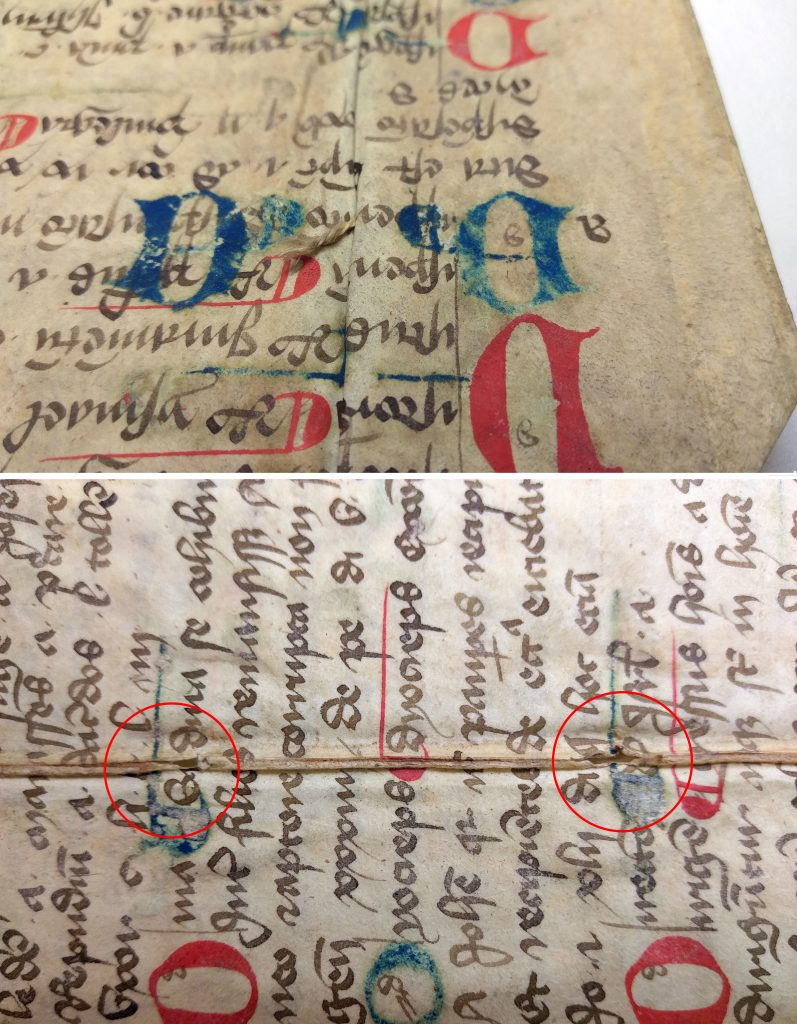

Luckily, if one has to remove tape, this type of tape is about as easy to remove as they come. The gummed adhesive layer on this tape responds very well and quickly to a light application of methylcellulose; after just a couple of minutes, the tape carrier and most of the adhesive lift away easily. I reduced the remaining adhesive residue by gently swabbing it with damp cotton, but I did not pursue this very far – overly aggressive cleaning would leave those areas of the parchment looking too starkly white. When the tape was all removed, I used a soft brush to dislodge some surface dirt that had accumulated in the creases.

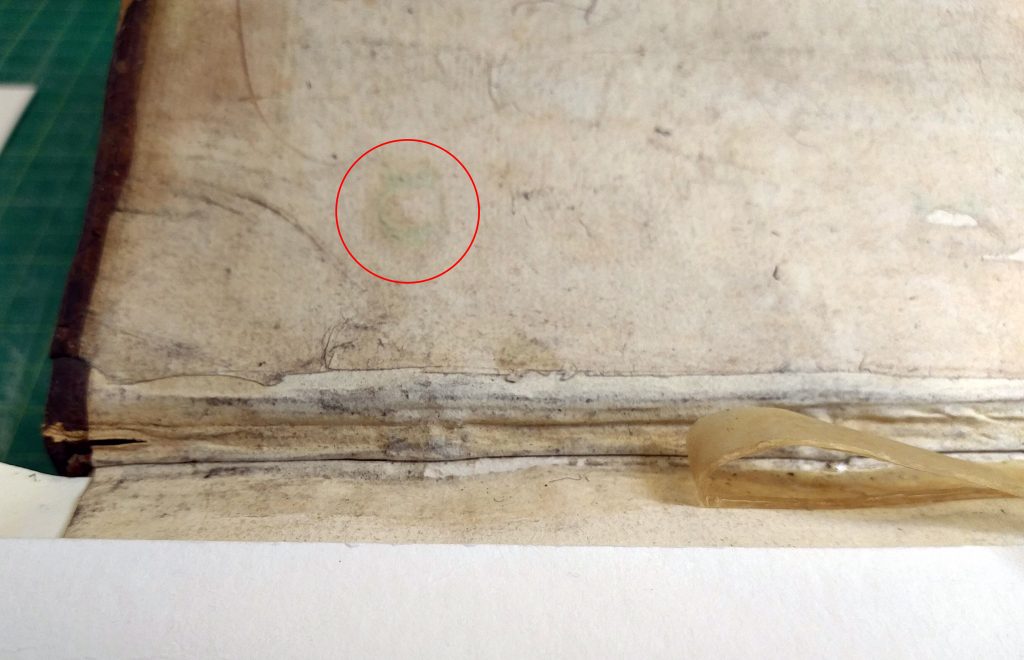

Removing the tape hinge that had held the fragments in place.

In the red circle, note the stain left by one of the blue manuscript capitals

from when the fragments served as binding material. Click image to enlarge.

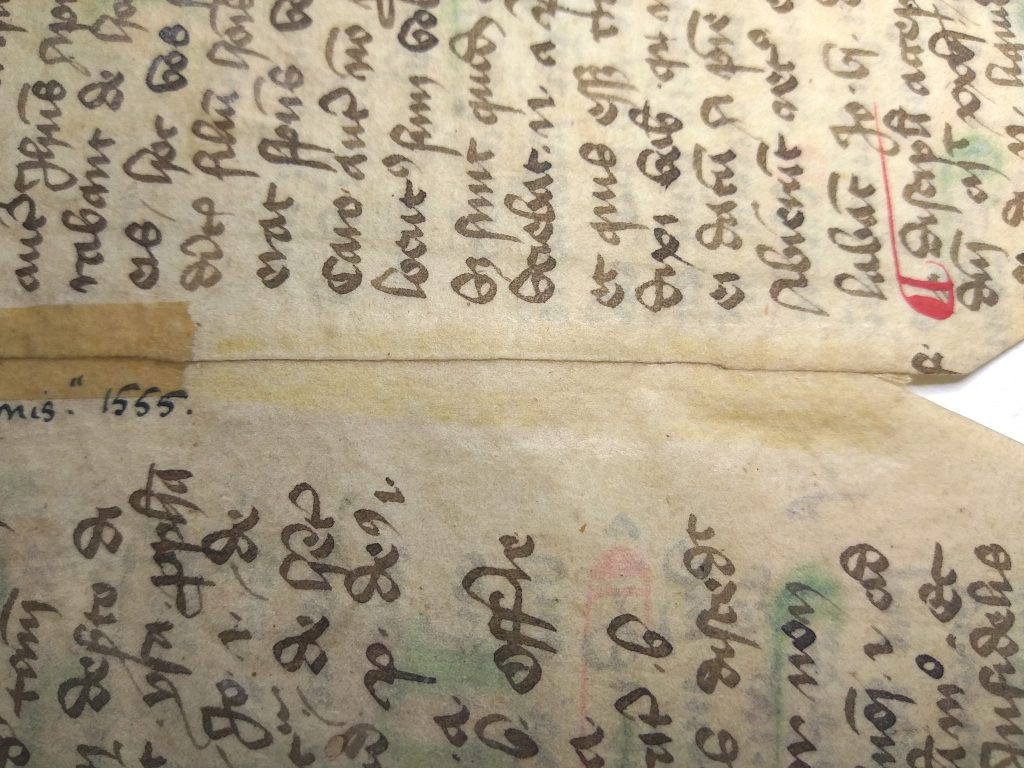

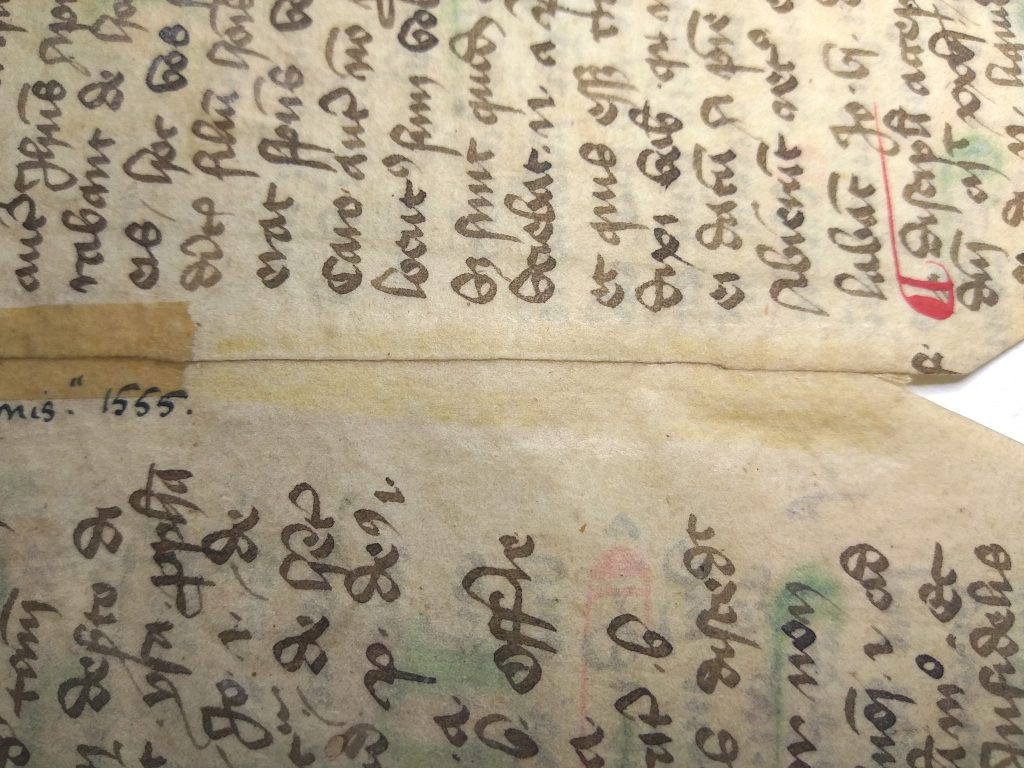

Detail of the seam where the two halves of this leaf were cut apart long ago.

Click image to enlarge.

Next, I used very dry paste and thin tissue to reattach the two halves to one another. I chose to do this in lapped sections rather than a continuous strip to allow the skins to expand and contract with subtle changes in the environment, and to distribute the stress of the repair evenly along both sides of the leaves, as well as to avoid placing adhesive over areas where ink was present. Finally, I reattached the fragments inside the lower board using a hinge of Japanese tissue and paste.

The finished manuscript fragments replaced into the volume.

Click image to enlarge.

Angela Andres

Special Collections Conservator

Conservation Services