Cracking the Codex: Reading Medieval Latin Abbreviations

August 1st, 2025This post was written Public Services student assistant Kit Cavazos as part of their summer internship supervised by KU English Professor Misty Schieberle and Special Collections Curator Eve Wolynes.

Although medieval manuscripts are well-known for their look and style, the act of actually reading and understanding one can be tough. The image that often comes to mind is that of their non-naturalistic drawings, and thus, a casual viewer may see the squiggles sprinkled across the text as another odd decoration. However, many serve specific and intentional functions, acting as contractions, substitutions, or abbreviations of words or parts of words. Scribes often chose this practice because it saved on ink and parchment space, since both these materials were quite expensive.

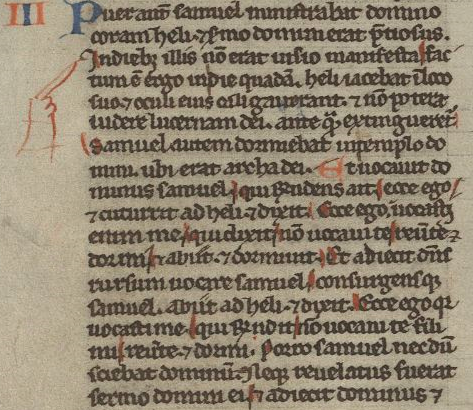

The first and most prominent thing to note about manuscript notation is the dashes that are most often placed over vowels. Most of the time, these indicate a missing letter N or M. For example, “terram” shortens to “terrā.” The page above has quite a few examples in the first line: “qua[m],” “lapide[m],” and “lapide[m].”

Dashes can often have other meanings when interacting with a consonant, either by hovering above or crossing the letter. The incipit line of the above page has a quite recognizable first word, which substitutes an I for a J. This letter difference is generally because Latin, as a language, does not use the letter J, meaning our first word is “Judea.” Thus it is easier to understand part of the next noun, which has a letter L with a dash intersecting it, with the result resembling a stylized letter T. Picking out when a letter is a T or an L is made easy by way of comparison, as the page’s script will always have a style that differentiates letter that could be confused.

Thus, this L with an intersecting dash in the spine could represent a few similar letter clumps: “ler…,” “…ul,” “lor…,” or “al…,” among others. Despite knowing exactly what variations the letter could stand for, it still introduces a new wrinkle into the fold, as none of the suggested meanings for the substitutions seem to make the word wholly understandable. “Jerlerm,” “Jerulm,” “Jerlorm,” and “Jeralm” are not proper words, and thus, the contraction demonstrates how common words (such as proper nouns) could have more of an abstract contraction. When examining this word in context, it might be a bit easier to understand that this contraction represents the city named “Jerusalem.”

Another common symbol is this: , which often represents a “rum,” “ram, or “rem” sort of ending. The above example has multiple instances of its use within the first line, all taking the first possible ending. The line, when uncontracted, would read “verbi salutaris ac miraculorum suorum dulcidine” (“by the sweetness of his saving word and miracles”). These textual changes – both contractions and substitutions – indicate that both scribes and readers needed to have not only a deep understanding of what each symbol represented, but also a sense of the language. You could either look at the Latin and parse some words, or you could understand how to complete the words but have their meaning completely lost on you. This afforded the literate members of the population some form of exclusivity from everyone else. These manuscripts often contain important information about plants, animals, or other general encyclopedic knowledge.

Another important aspect of a manuscript is additions that enhance a reader’s understanding of the text. The most obvious would be the fingers pointing to specific lines. These are manicules, and they are meant to emphasize important parts of the text. Another detail does something similar on the above page. The red lines highlighting specific letters are forms of rubrication, and they have a very similar function to manicules. In this instance, they mean to indicate and emphasize the capital letters in the line.

In other instances, rubrication notates significant parts of the text and frequently has a moralizing meaning. This means it can also come in textual form – often called the rubric – and it can add, emphasize, or reiterate important information to the reader. The term rubrication comes from the Latin word “ruber” (“red”), but important elements to a manuscript are not restricted solely to one color. Red often sees the most use, but blue and occasionally green can also be used for emphasis or decoration.

With these basic understandings of common aspects of a medieval text (at least within the Spencer collection), reading a manuscript for the first time may be less daunting. The above page, for example, has several features already discussed. Most prominently, the rubrication stands out from the rest of the content, especially in the rubricated initial letters A and I, which have blue decoration that appears to mimic a lace design. The first rubricated word of the text is in the incipit line, which has the same L with an intersecting dash as before. Thus, we know the word would be something like “pp[ul]m” or something similar. If you don’t have a book on contractions easily to hand, sometimes sounding out what letters you do have can help make sense of the word – “populum,” in this instance. Thus, reading through the incipit line, it would say something like “Absol[v]e q[uaesumu]s D[omine] p[o]p[u]l[um] n[ostr]o[rum] vincula peccato[rum]” (“we beseech you, O Lord, to absolve our people from the bonds of their sins”). From even just this first line, we can understand that the reader is meant to focus on the people or population about whom it is speaking.

Reading through a medieval text can be difficult; even just reading one line without translation can take hours, depending on how many contractions or abbreviations there are, as well as how obscure each one may be. The result, though, is quite often rewarding, as it means modern readers can understand how information was relayed and what information medieval writers saw as needing to be relayed. An online resource for information on specific abbreviations is Cappelli’s Latin Abbreviations, which has been incredibly helpful for research and compiling the transcription of these lines.

Kit Cavazos

Public Services student assistant

![Full view of the map Nova totius terrarum orbis tabula Amstelaedami...by Frederik de Wit, [173-]. Call Number: Orbis Maps 1:5.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Orbis-Maps-1.5-B-1024x881.png)