African American Migration from Kansas to California

February 12th, 2019The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) founded the annual February celebration of Black History in 1926 and has identified Black Migrations as the theme for 2019. To demonstrate African American migration in the United States, I chose the Anthony Scott family papers from Spencer’s African American Experience Collections. The papers tell the story of the migration experiences of two families who lived in or came to Kansas.

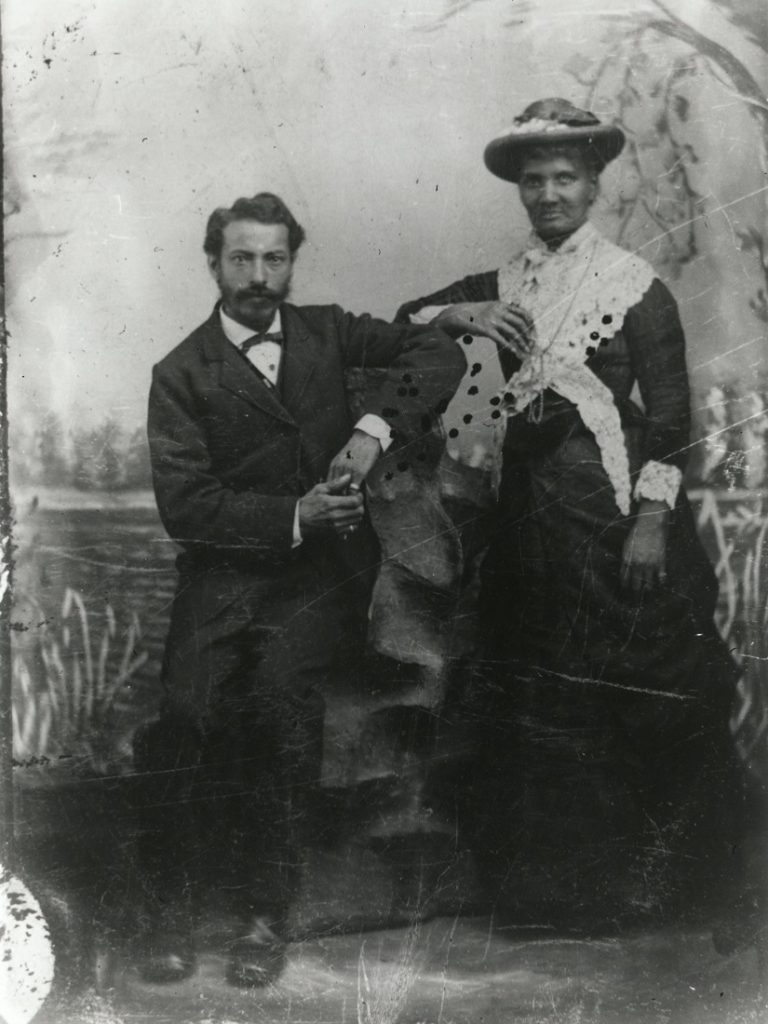

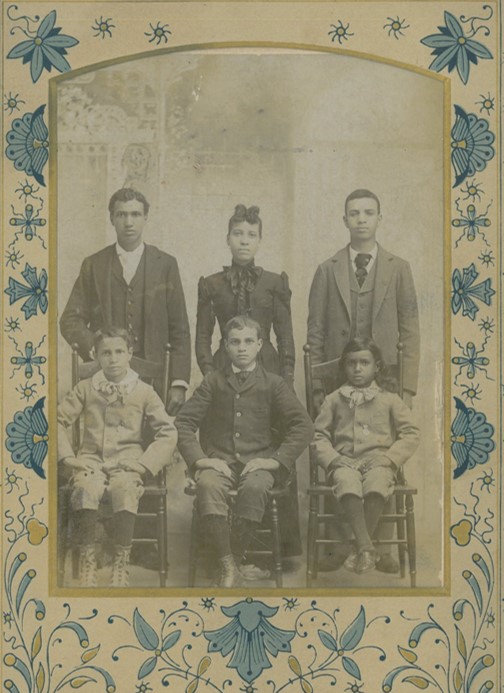

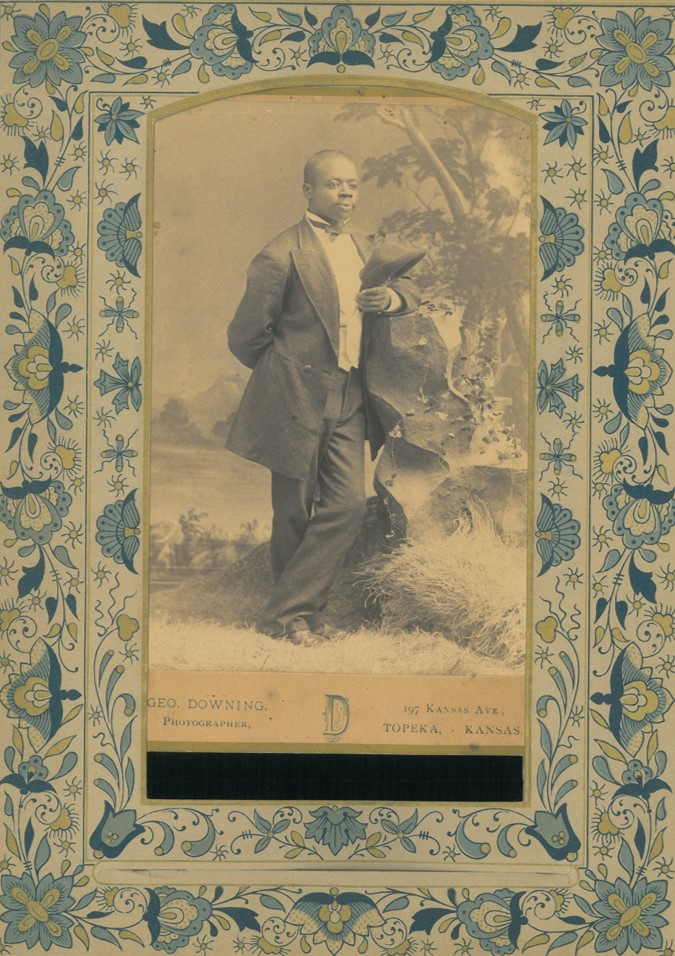

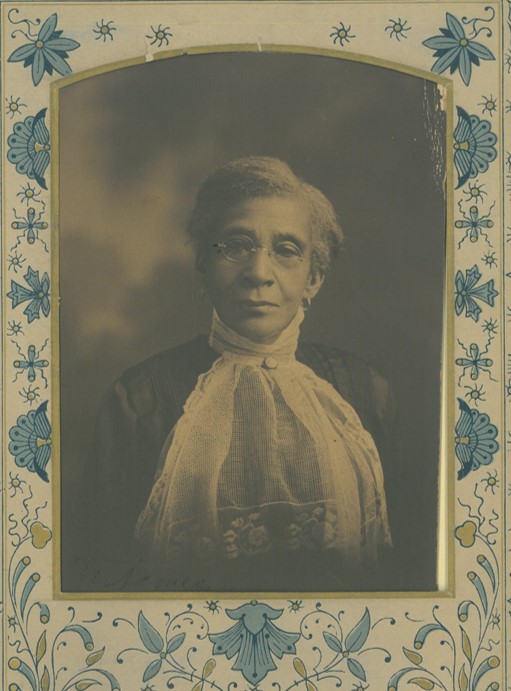

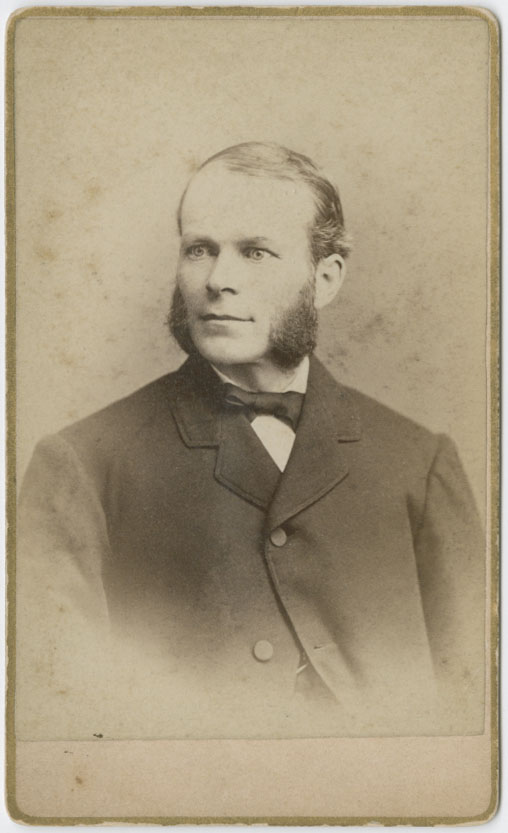

Anthony Scott was born in Kentucky in 1846. He and his wife Anna had five children: James, Thomas, Elder, Mary, and Alvin. In 1880, Anthony and Anna moved their family from Kentucky to Topeka, Kansas.

Anthony and Anna Scott in Topeka, 1895. Anthony Scott Family Papers.

Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

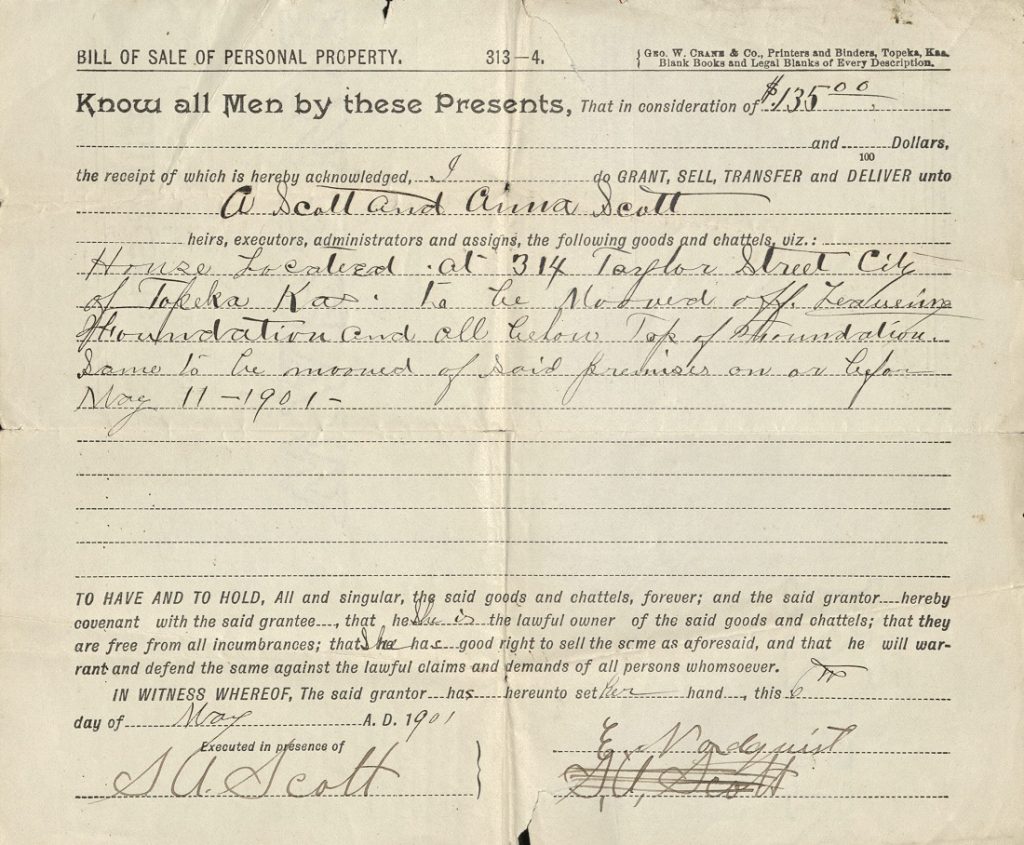

A bill of sale for a home on Taylor Street in Topeka purchased by Anthony and Anna Scott, 1901.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

James, the eldest son of the Scott family, staked out land and established a homestead in the Cherokee Outlet (now part of Oklahoma) in 1890. However, shortly after the turn of the century James returned to Topeka, where he met Lenetta Brasfield. They married on August 18, 1903. The couple had seven children: James Jr., Luther, Raymond, George, Charles, Bessie, and Thelma. Around the same time, Thomas Scott, James’s brother, moved to Chicago.

James Scott’s ranch in Oklahoma, circa 1895. Anthony Scott Family Papers.

Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

Lenetta Scott with sons George and Luther outside the family’s home in Topeka, 1915.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

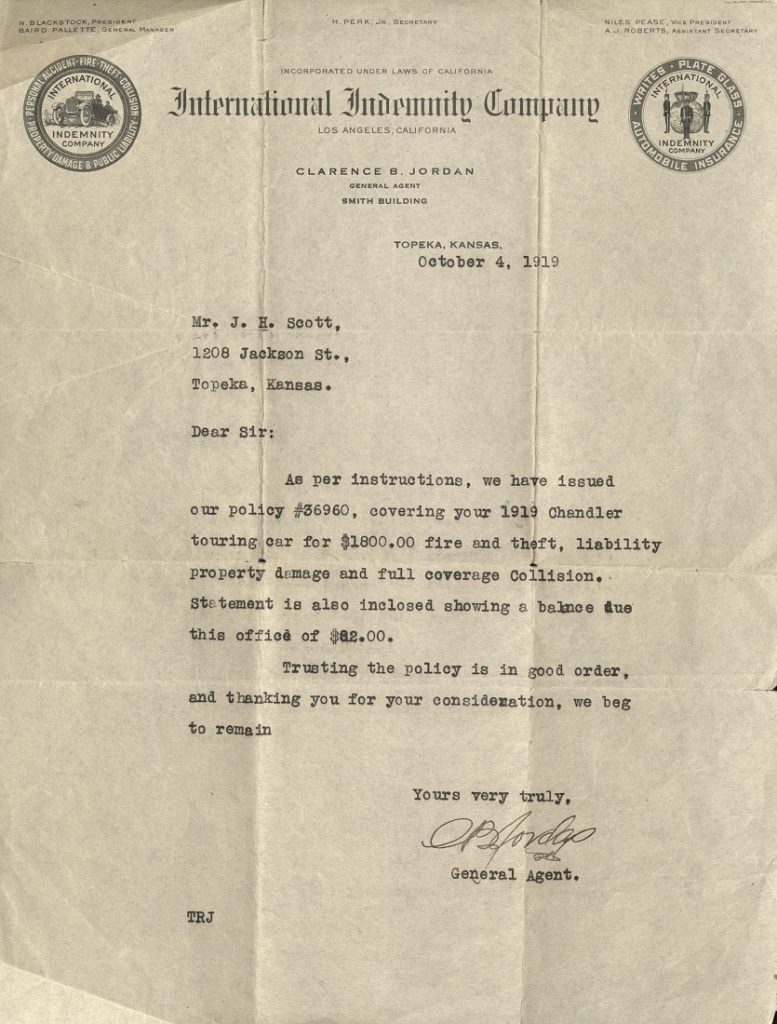

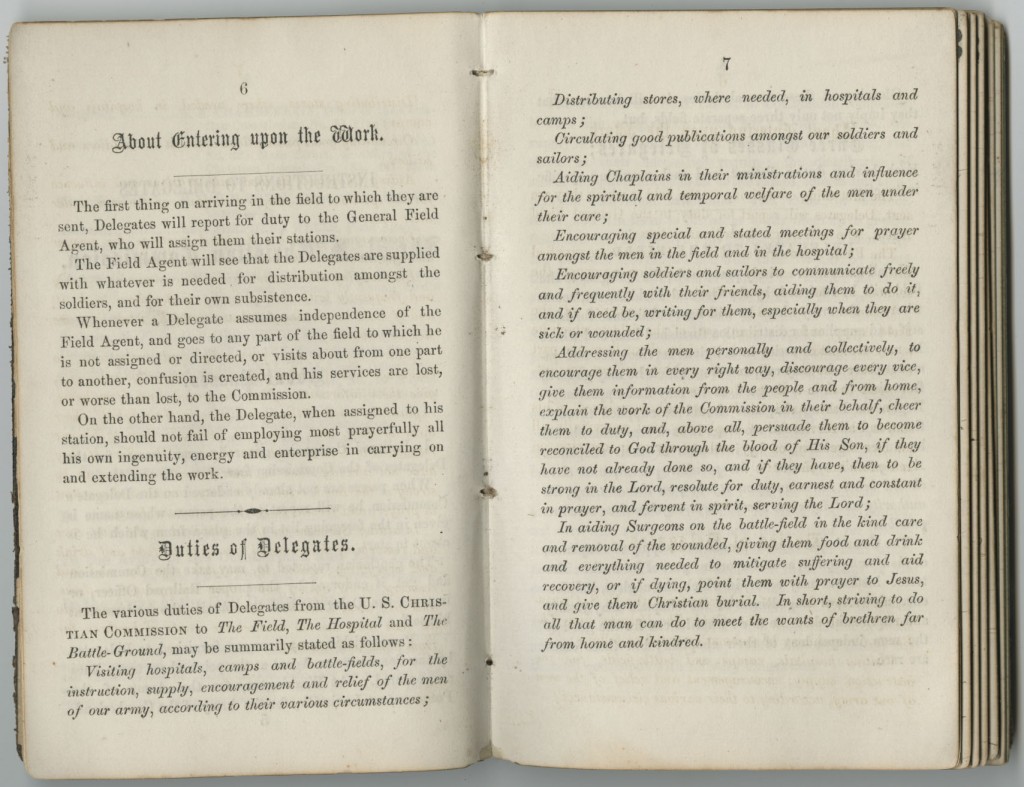

In 1919, James Scott purchased an insurance policy for a Chandler touring car. The Scotts used this car on their thirteen-day journey from Topeka to Los Angeles later that same year.

James Scott’s insurance policy for the Chandler touring car, 1919.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

The James H. Scott family, 1919. Front row, left to right: Lenetta Scott, Bessie Scott,

Amanda Adkins, Raymond Scott, George Scott, Luther Scott, Thelma Scott,

James Scott Jr., Erma Scott, and James H. Scott; people in the car unknown.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

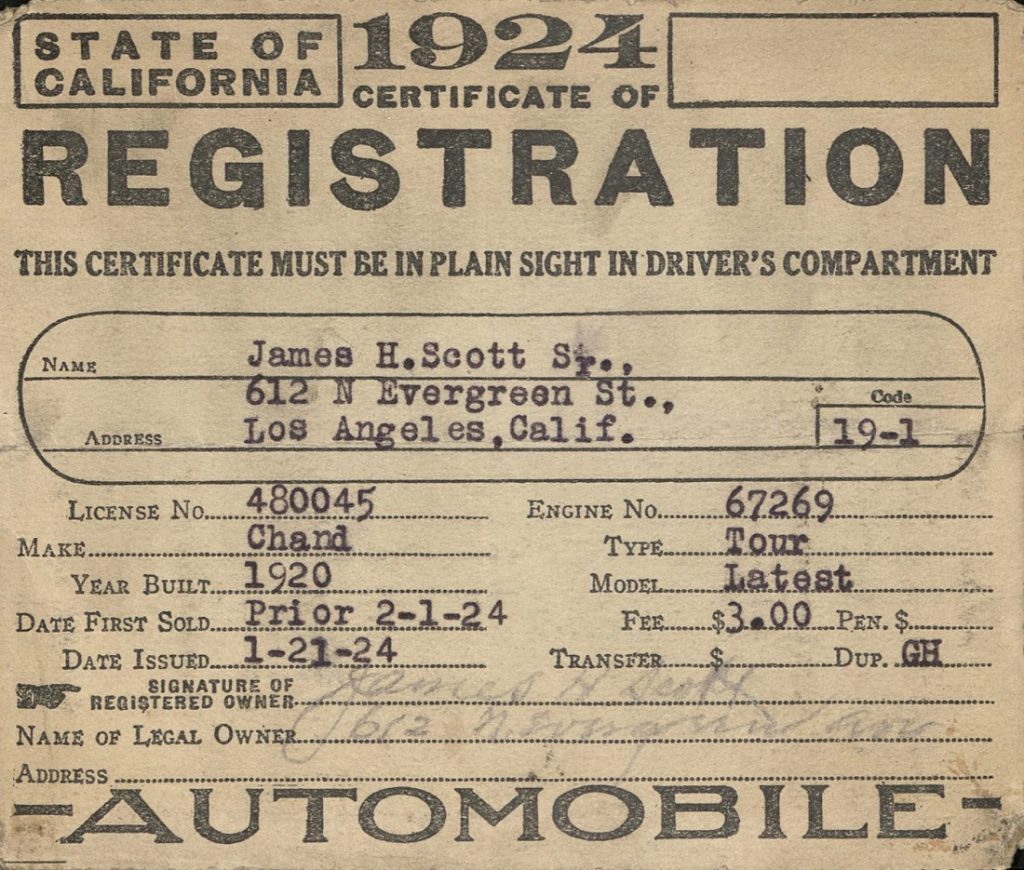

James Scott’s California registration for a 1920 Chandler touring car, 1924.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

The James Scott family settled in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles upon their arrival in 1919 and lived at the same address until 1962.

The Scott family home in Los Angeles, 1950. Anthony Scott Family Papers.

Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

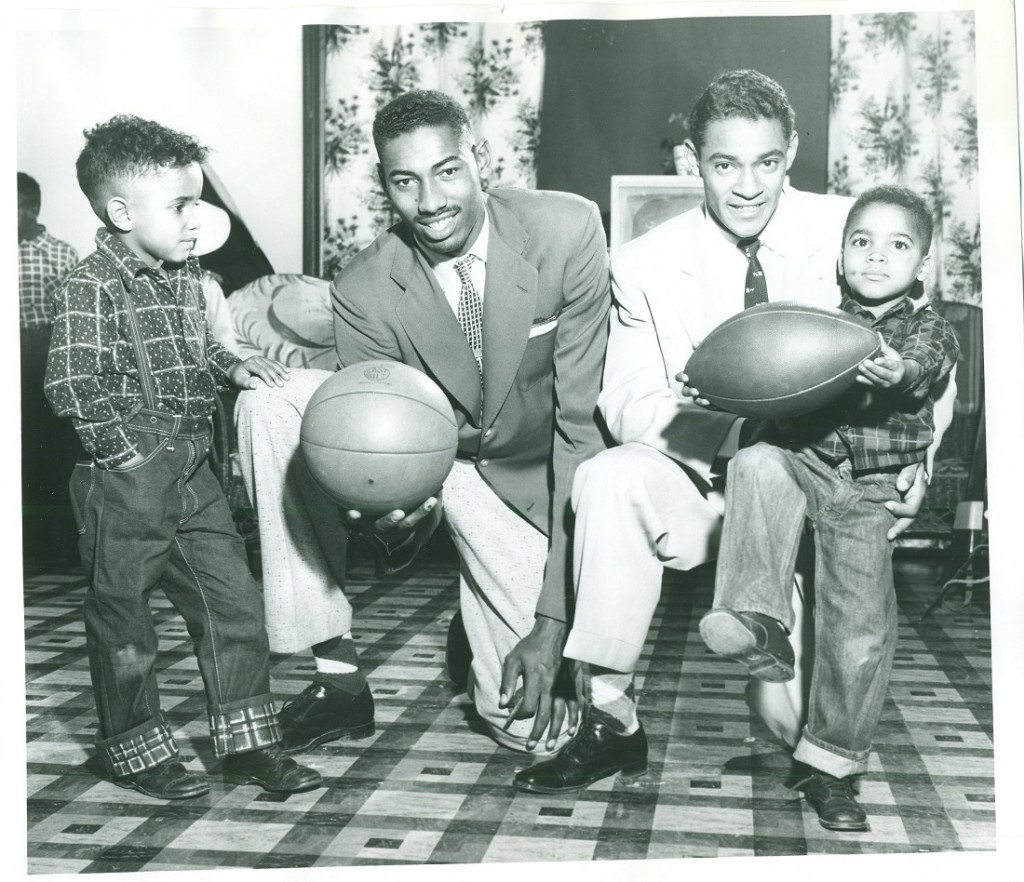

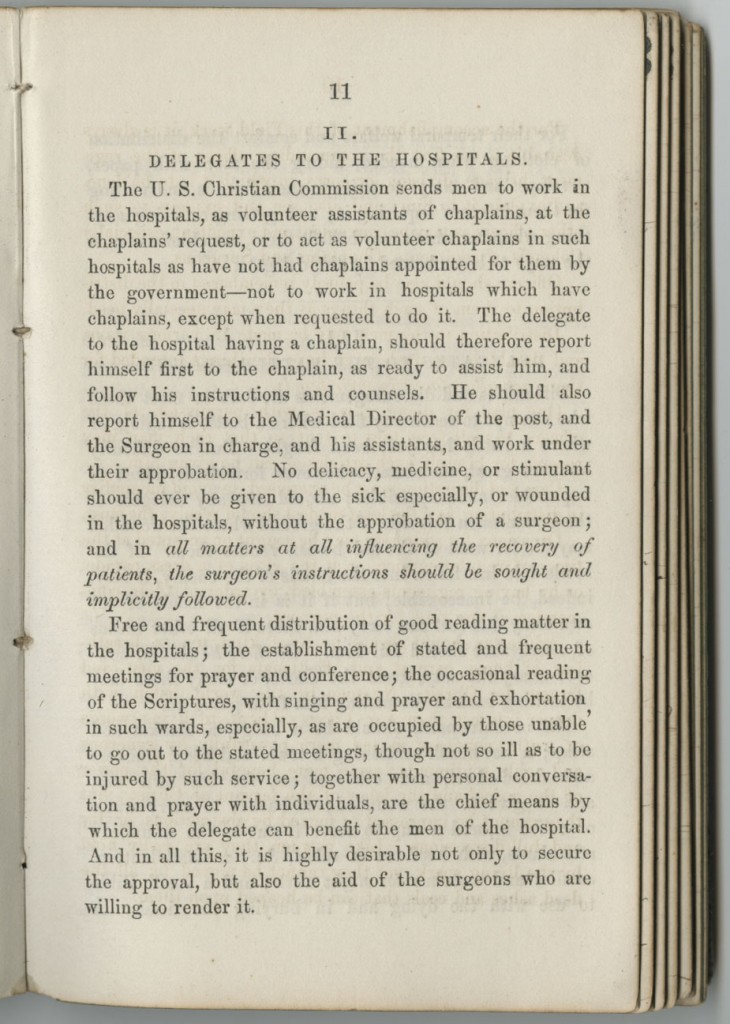

Thelma Scott – the youngest daughter of James and Lenetta Scott – met her husband, Grant D. Venerable, in Los Angeles. Mr. Venerable (pictured with the family below) was born in Jackson, Missouri, in 1905. He became the first African American to graduate from the California Institute of Technology in 1932. Grant D. Venerable’s older sister Neosho once lived in Lawrence; she graduated from the University of Kansas in 1914.

The James H. Scott family dinner session of the Kansas Club in the Venerable home, 1946.

Front row, left to right: Elizabeth (Pettus) Moore, James Scott, and Lenetta Scott.

Back row, left to right: Thomas Moore, Erma (Scott) Moore, Mildred Moore,

Thomas Moore Jr., unknown, Thelma (Scott) Venerable, and Grant Venerable.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

Mr. and Mrs. Venerable had three children: Delbert (Grant D. Venerable II), Lynda, and Lloyd.

Thelma (Scott) Venerable and Delbert Venerable in California, 1944.

Anthony Scott Family Papers. Call Number: RH MS 676. Click image to enlarge.

Delbert Venerable, son of Grant D. Venerable and great-grandson of Anthony Scott, graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles in 1965. He went on to receive his Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the University of Chicago in 1970. He was awarded the United States Atomic Energy Commission Fellowship for his research into radiation biology. He taught chemistry in both high schools and universities in the 1970s and went on to work in Silicon Valley as a systems scientist in the 1980s. From 1992 to 1999 he was the CEO of Venteck Software Inc.

Dr. Venerable became a part of the development of a new field of study combining science, history, and ethnic studies. He continued in the 1990s to maintain positions of administration or professorship at various universities. His publications have included books, scientific paintings, academic articles, and editorials.

The Scott and Venerable families illustrate the importance of migration as a major theme in the African American historical experience.

Elaine Kelley

African American Experience Student Assistant