That’s Distinctive!: Aaron Pugh’s Civil War Diary

July 5th, 2024Check the blog each Friday for a new “That’s Distinctive!” post. I created this series to provide a lighthearted glimpse into the diverse and unique items at Spencer. “That’s Distinctive!” is meant to show that the library has something for everyone regardless of interest. If you have suggested topics for a future item feature or questions about the collections, you can leave a comment at the bottom of this page. All collections, including those highlighted on the blog, are available for members of the public to explore in the Reading Room during regular hours.

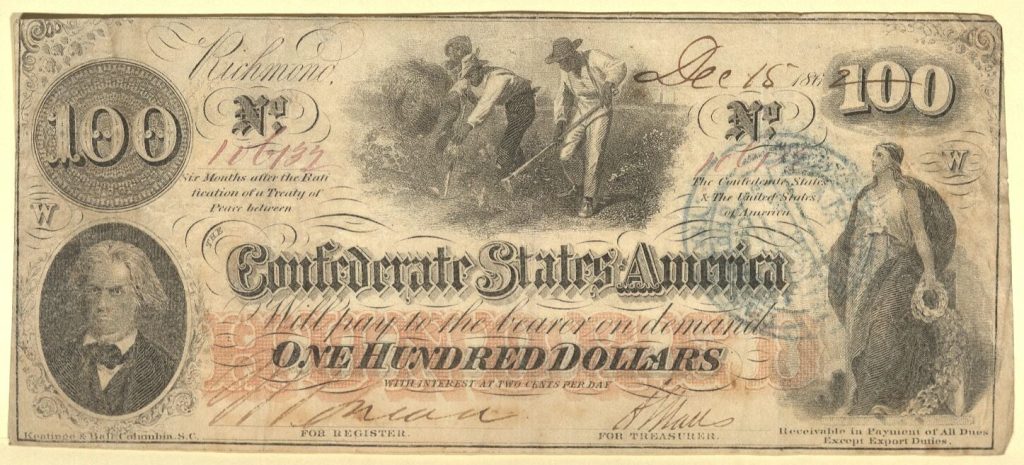

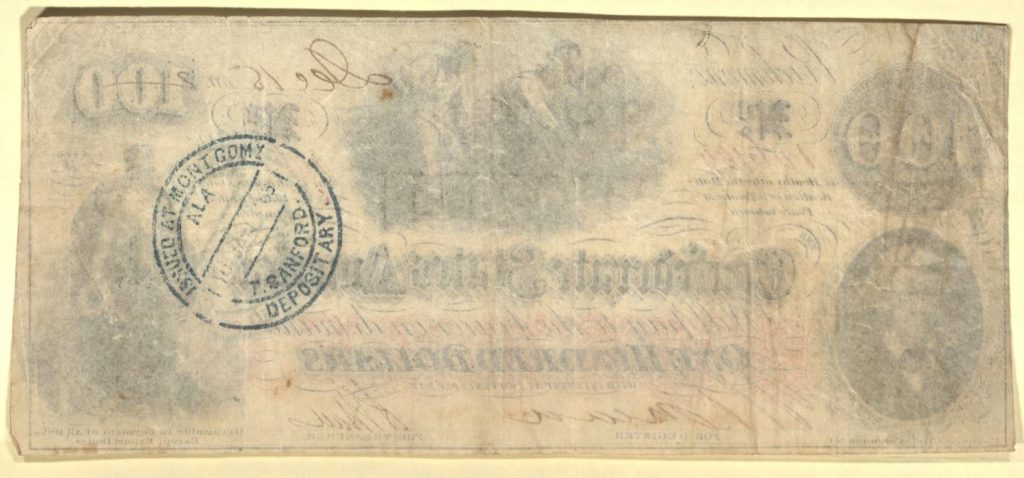

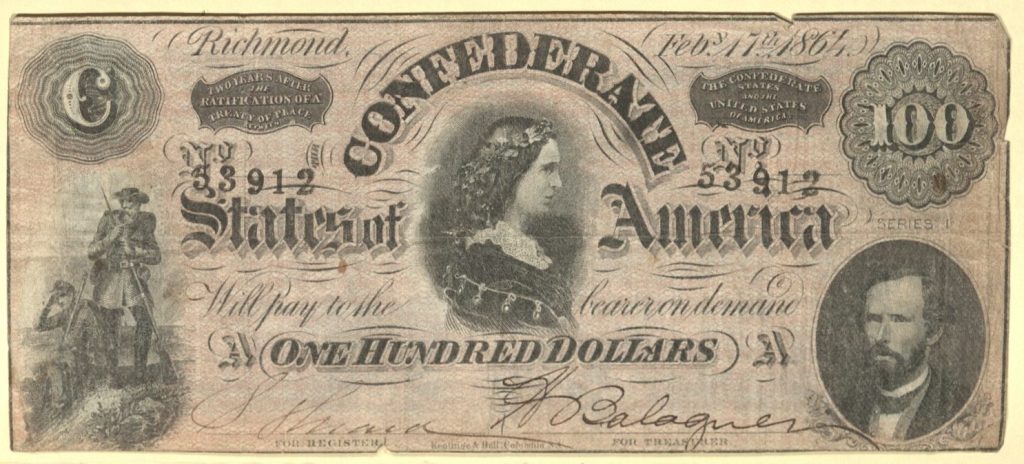

This week on That’s Distinctive! I am sharing a Civil War-era item from the Kansas Collection. My research for this post sent me down a rabbit hole of sorts finding new and interesting information at every turn. It has been a while since I have found an item that has piqued my interest as much as this one has and I am truly excited to be able to share it on the blog for others to see. At face value, the item itself might seem quite boring, but it is the story the item tells that truly resonates with the viewer. That’s the thing with housing rare materials: much of it might seem “useless,” but you never know what that one newsletter, postcard, banknote, diary, etc. might mean to someone and their research. Much of what the library houses is about preserving history for future generations to access.

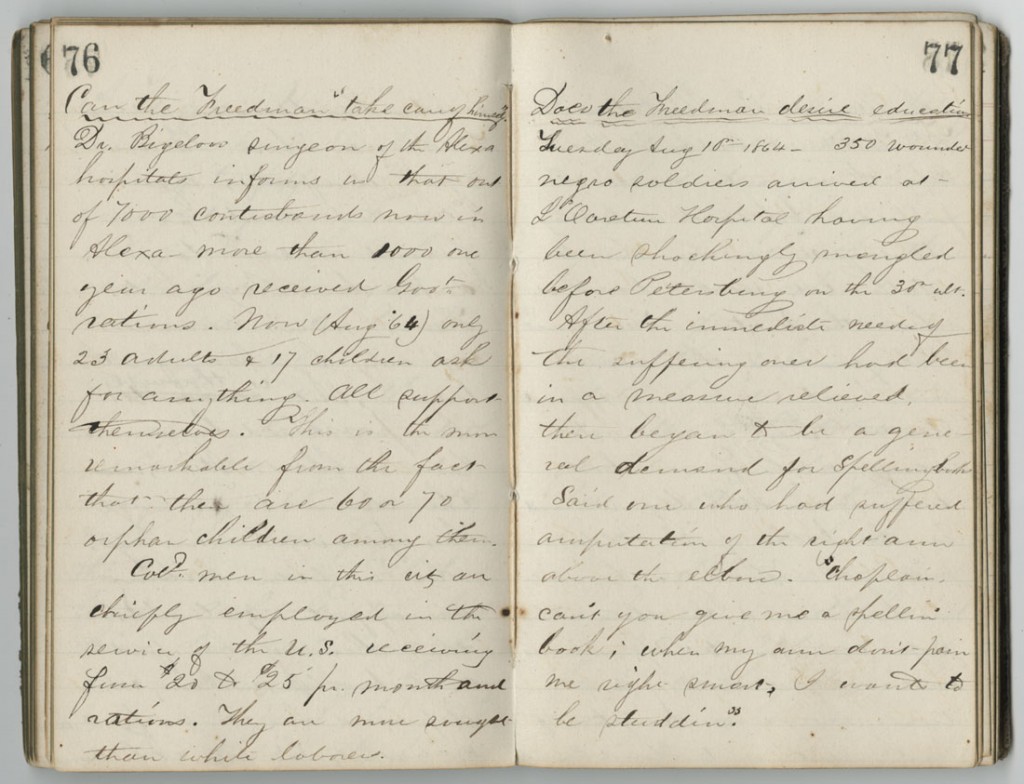

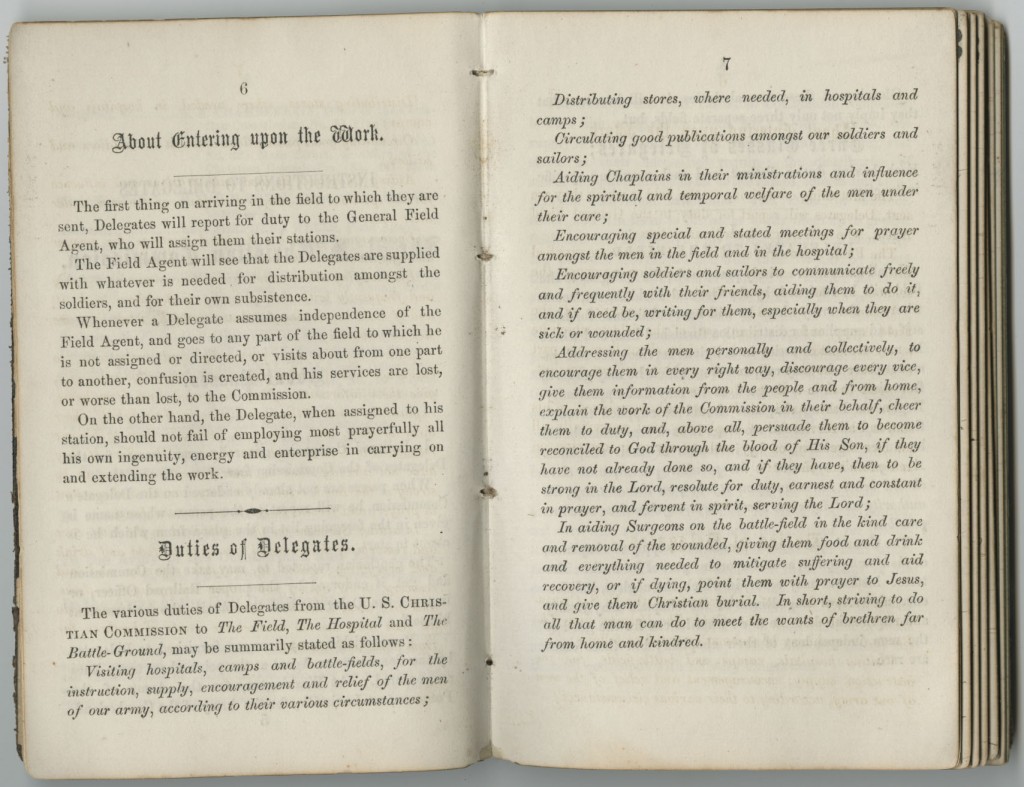

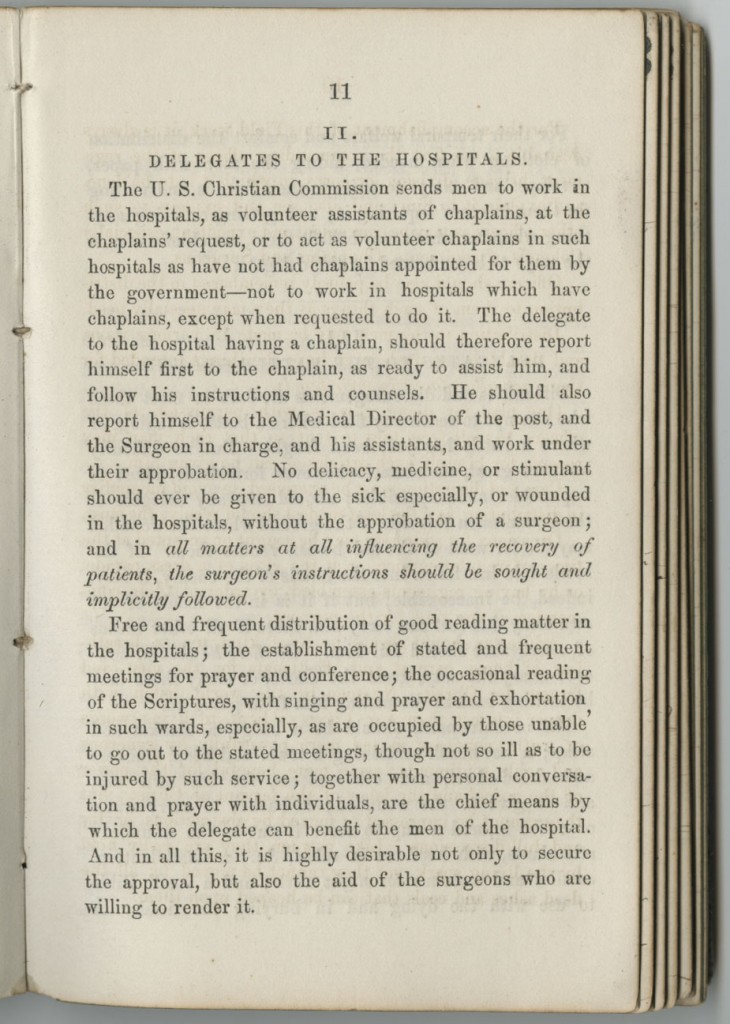

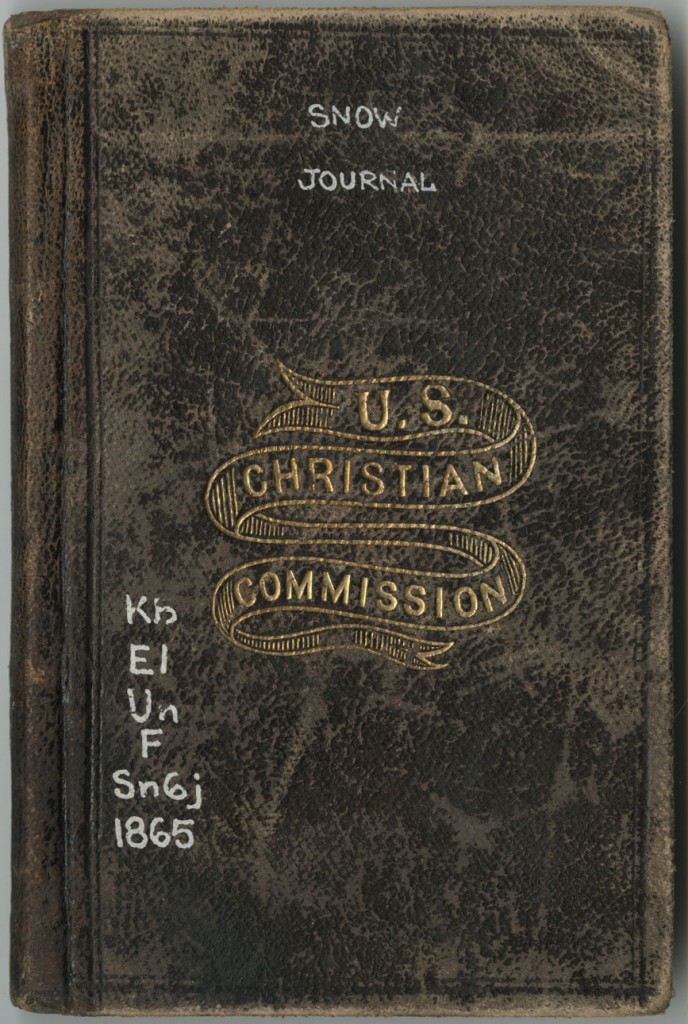

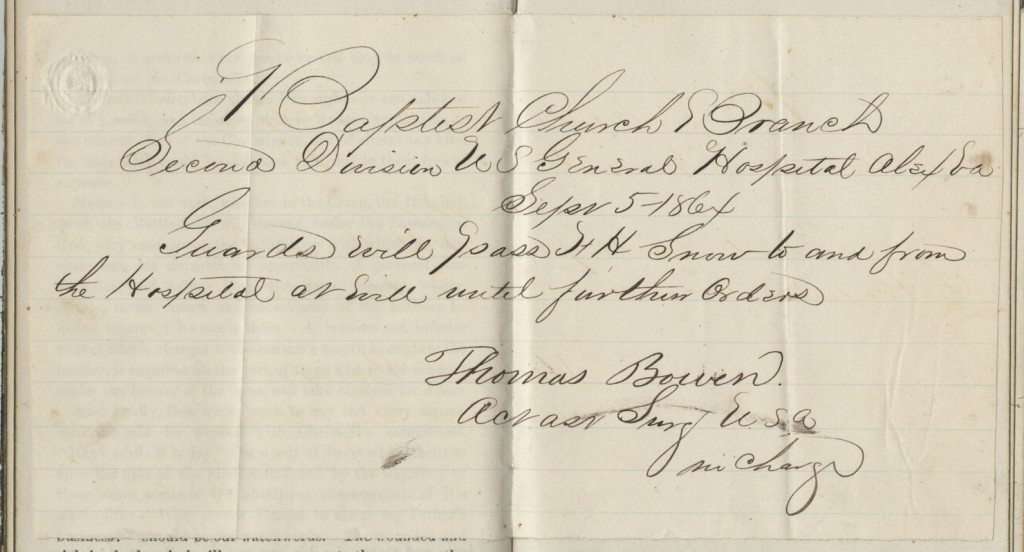

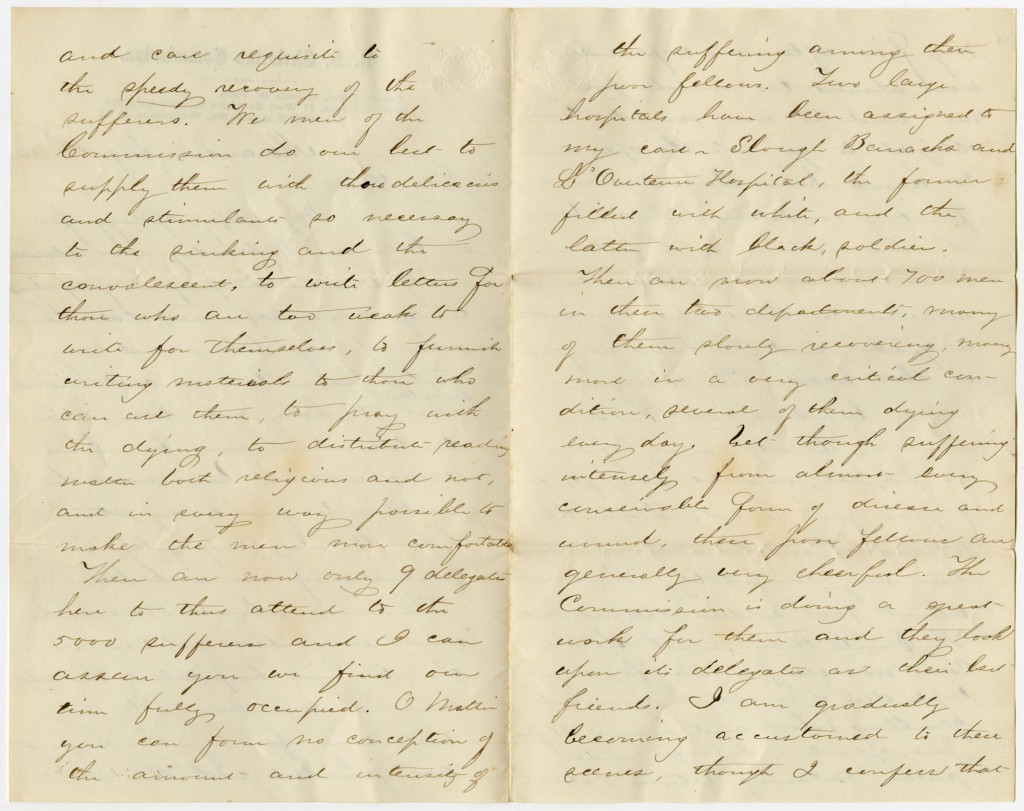

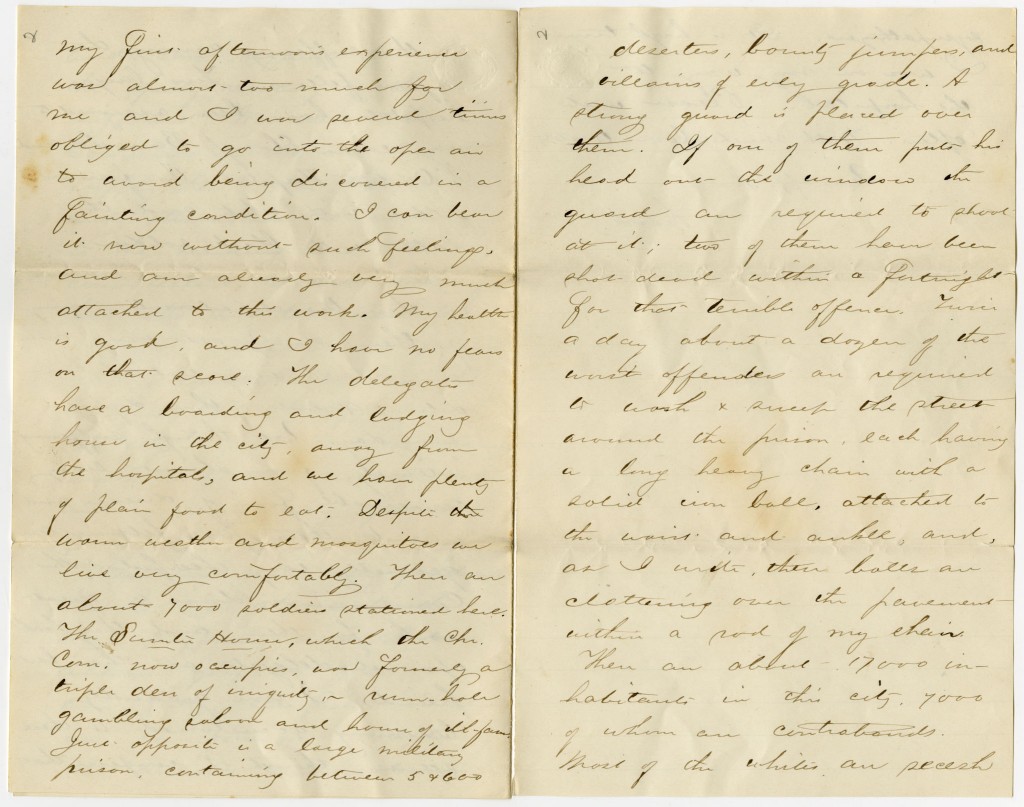

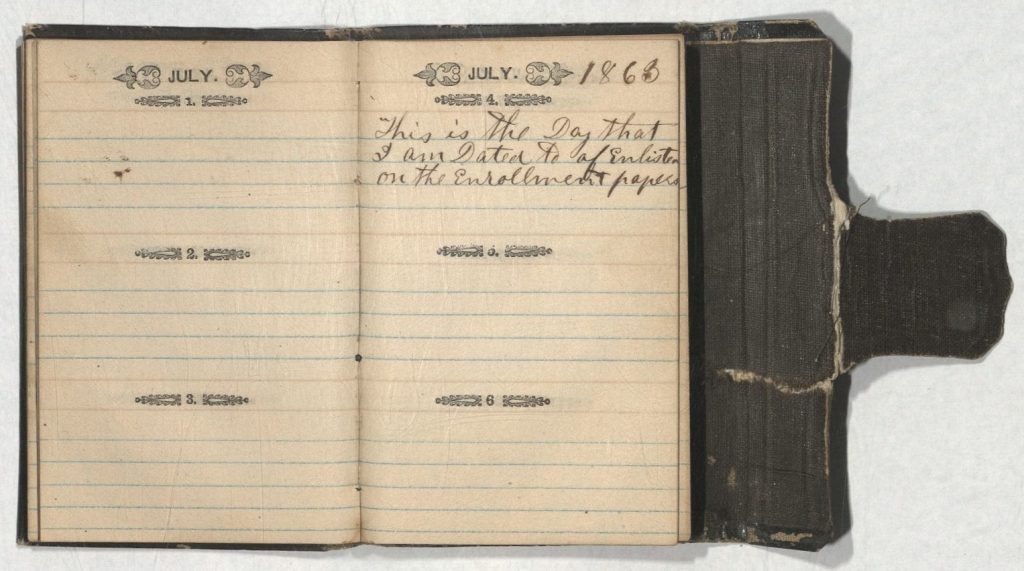

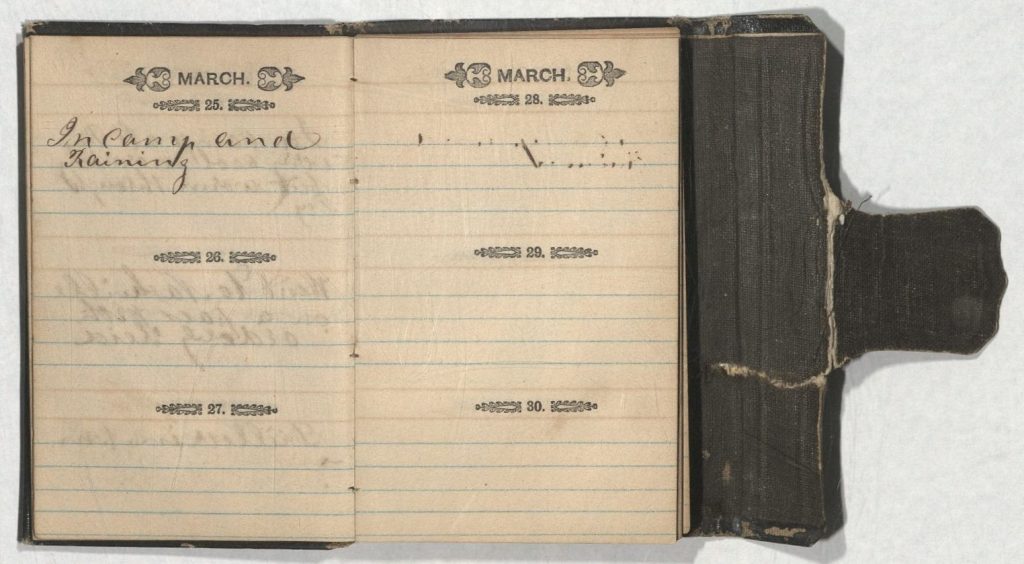

The item I am highlighting is a daily journal (diary) that belonged to Aaron Pugh. From the finding aid, Aaron Pugh was born in Carrol County, Ohio, on January 21, 1833. Aaron enlisted in the U.S. Army on July 4, 1863, at the age of 30. The 1860 federal census says that, prior to joining the Army, Pugh was a (married?) farmer in Marcy, Iowa. Preliminary research indicates that the diary follows Pugh’s life from approximately July 4, 1863 to March 25, 1984. As a side note, I actually stumbled upon this item by looking for Fourth of July items. That’s the fun of finding aids; sometimes search terms bring up somewhat unrelated but still quite interesting results. Once enlisted in the Army, Pugh was a soldier in Company M of the 8th Regiment of Iowa Cavalry. IAGenWeb, a side project of the free genealogical website USGenWeb, lists a roster of the members of the 8th, which includes an entry for Pugh. The roster says that Pugh entered the Army as a Fourth Corporal and was promoted to Second Corporal March 26, 1864. March 26th is where the diary entries come to an end.

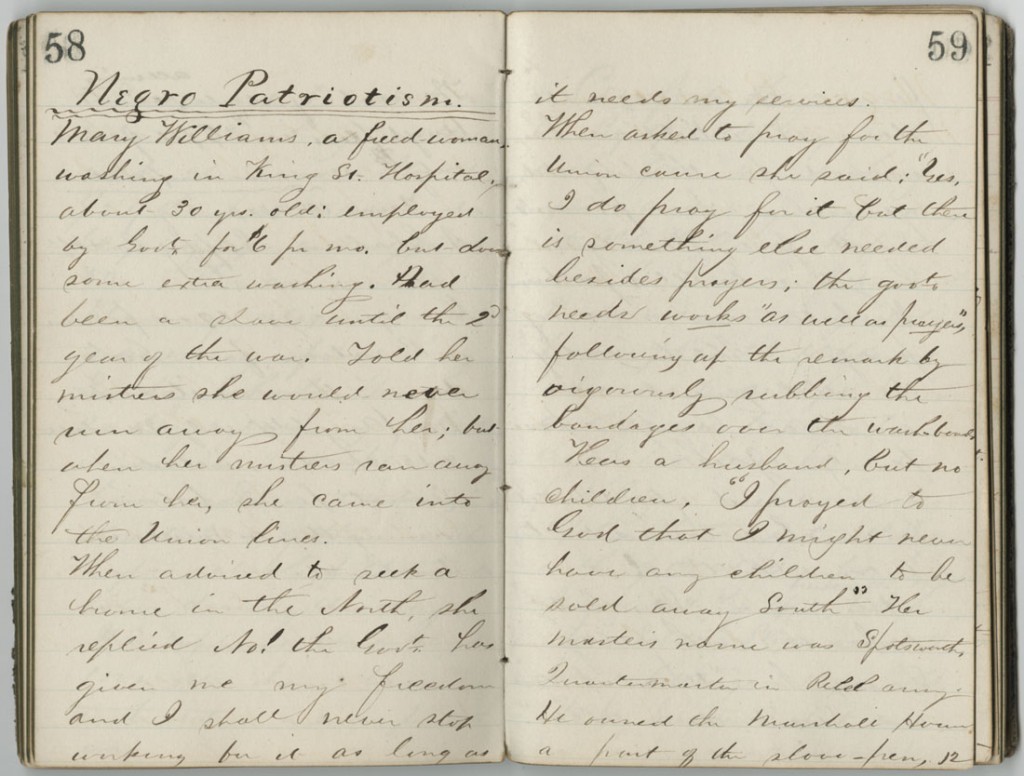

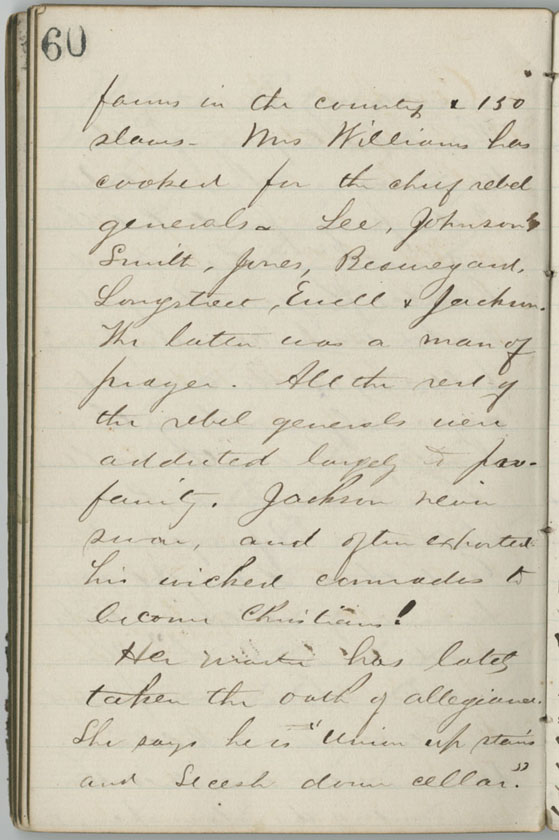

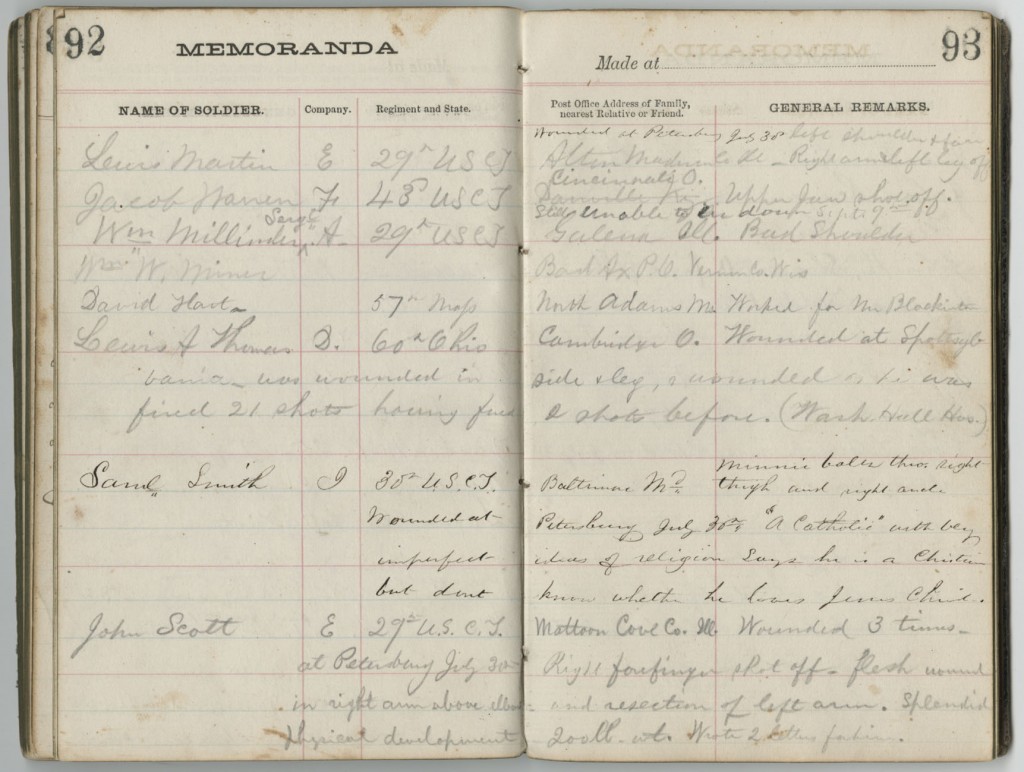

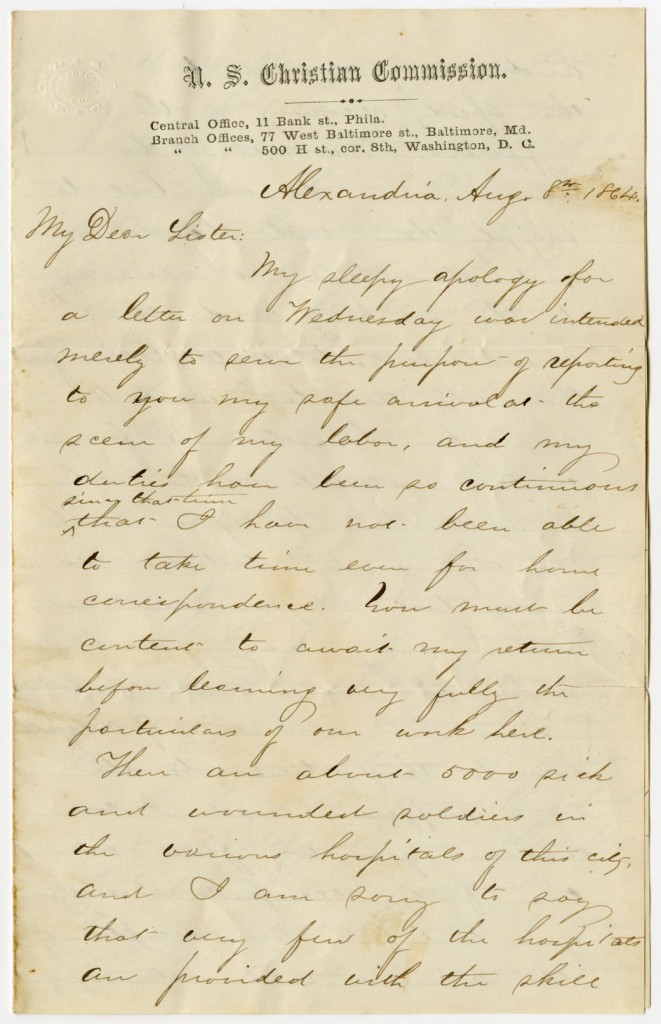

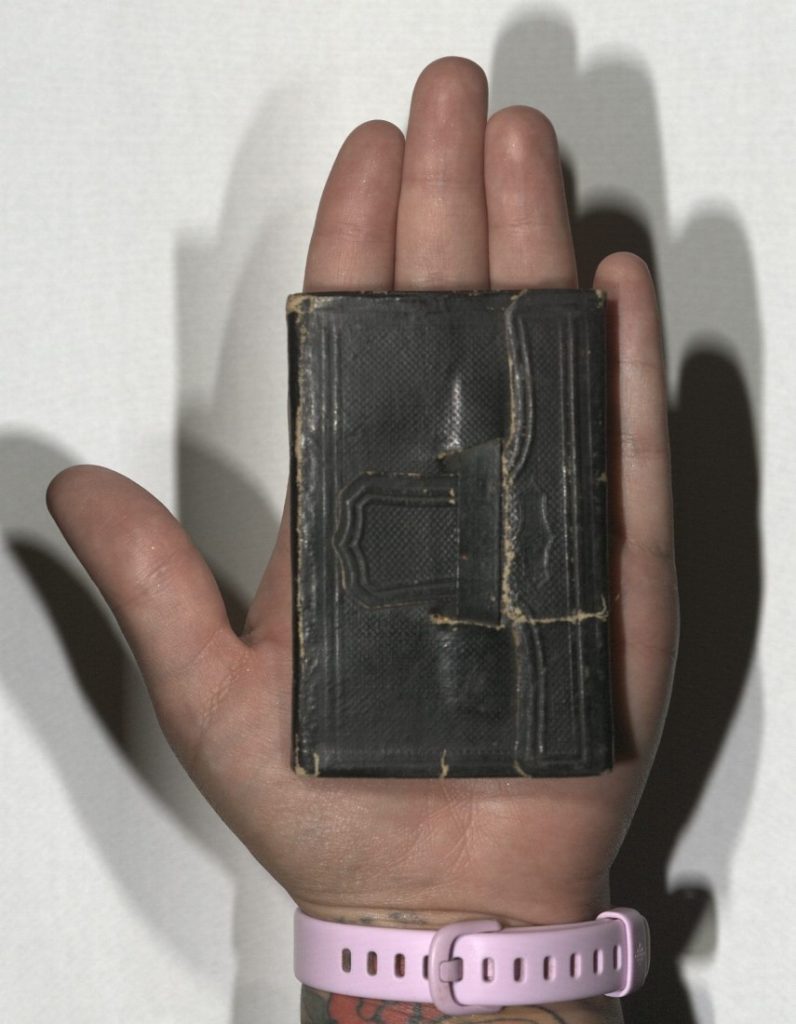

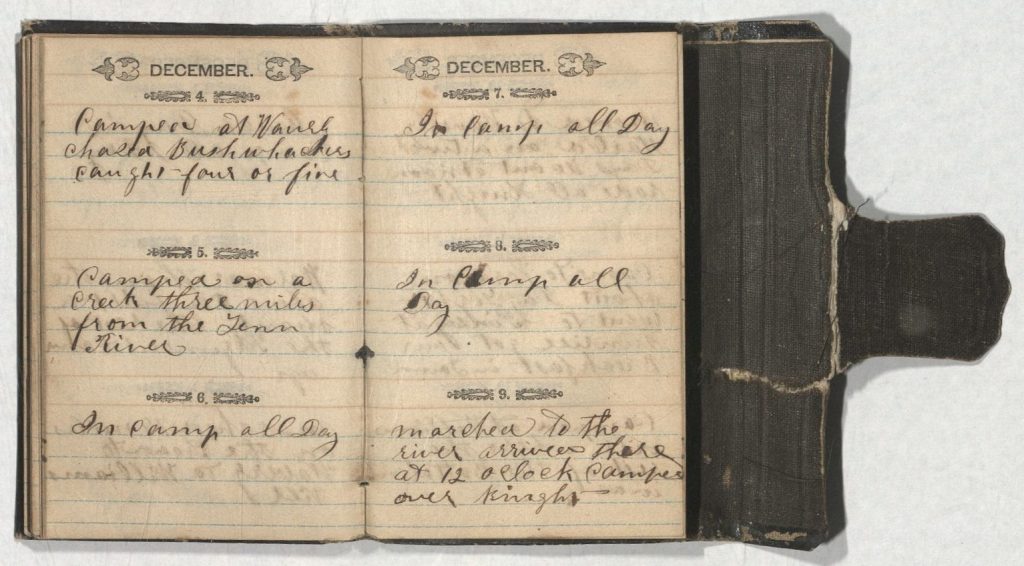

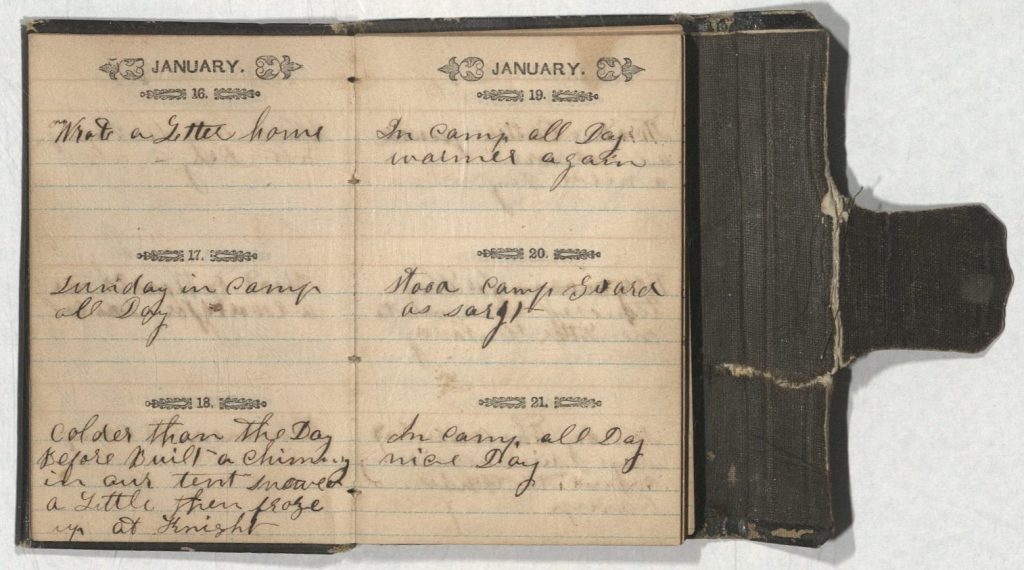

Much of the diary contains basic daily entries commenting on the weather or stating that the unit had stayed at camp or moved camp. Some entries are more in-depth about trips Pugh went on or letters he wrote. The diary is slightly larger than my palm with three days per page, which leaves little room for entries. When first looking over the diary, I thought it was cool but didn’t feel it was worth sharing. I wasn’t sure there was much to write about or anything that would draw users in. However, through a basic search of Aaron’s name and the dates of the diary I found that the University of Iowa houses a collection of letters that he wrote during his time in the Army. A few of those letters coincide with entries in Pugh’s diary. I one letter, from December 8, 1863, he writes to his friends about where his unit had been camping and how things were going. He notes that they had taken some thirty prisoners in recent times. He also states that in the last few days “we chased some forty [,] five or six miles and captured several there.” This is where it gets interesting because looking back in the diary, there is an entry on December 4, 1863, that says “chased Bushwhackers caught four or five.” The combination of the letter and the diary really gives you a glimpse into what Pugh was experiencing at the time. The next few days in the diary go back to mentioning being at camp all day as if nothing ever happened. Another letter on January 16, 1864, also coincides with the diary. While the letter seems to just be a general update to his friends, Pugh notes in his diary that he “wrote a letter home.” Making the connection between the letters and the diary adds a layer of excitement to the journey the items take the reader on.

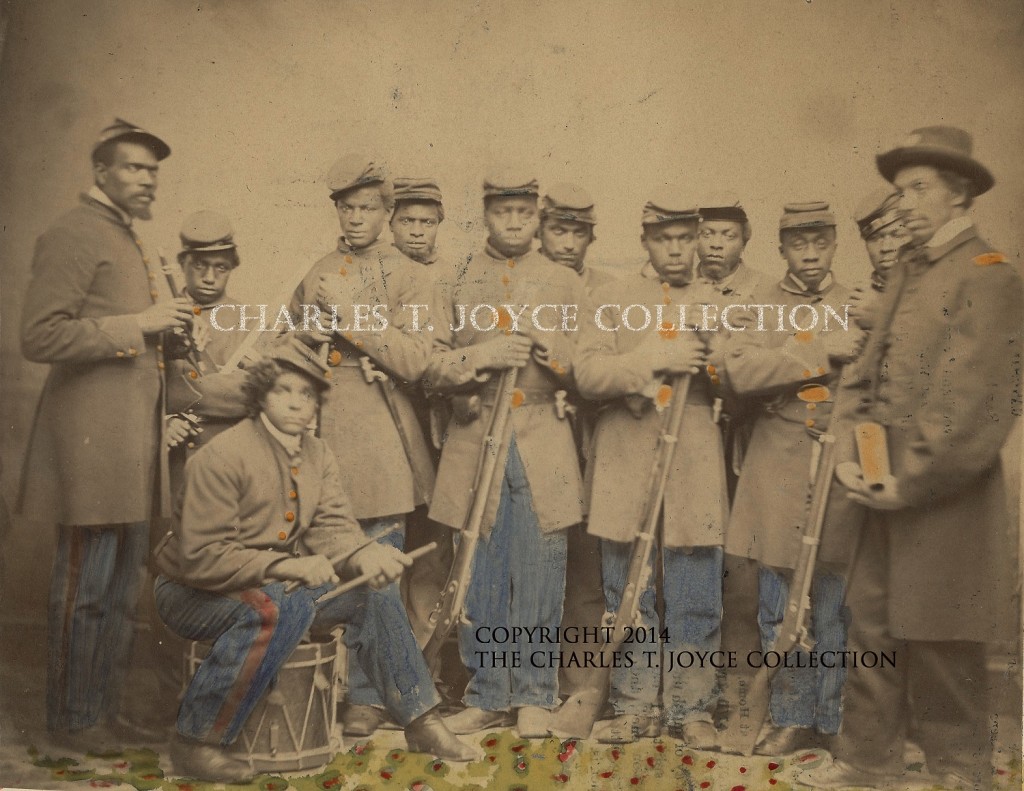

Between the diary, letters, and online resources one can follow the journey of Aaron Pugh and his regiment through the Civil War. On July 30, 1864, Pugh was captured as a prisoner-of-war during McCook’s raid on the Atlanta and West Point Railroad near Newnan, Georgia. Pugh died a prisoner-of-war at Andersonville, Georgia, on October 4, 1864. Records from the time list his cause of death as “scorbutus,” i.e. scurvy. Pugh is buried in Andersonville National Cemetery, plot 10297. There is also a memorial to Pugh in Hill Cemetery in Boone, Iowa. Historic photos of Andersonville prison – taken when Pugh was there – are available online through the National Park Service.

It took a lot of digging to find some information on Pugh and the events he may have endured but in the end, I feel it was worth it. Until I stumbled upon it, the item had no past transactions of being used. I feel like now it has a new level of meaning and might someday be of use to a researcher.

Tiffany McIntosh

Public Services