On Sunday, PBS will air the final episode of a six-part miniseries called Mercy Street, set at a Union hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, during the Civil War. This is the second of two blog posts that will explore a Spencer connection to that program; it’s an excerpt from a longer piece to be published later this year. Both entries have been guest written by Spencer researcher Charles Joyce. Mr. Joyce is a labor attorney in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and also a long-time collector and dealer of Civil War photography.

In my previous blog post, I introduced readers to an early KU professor and Chancellor of KU, Francis Snow, and linked his life to the PBS miniseries Mercy Street. The physical bridge between the two takes the shape of a seven by five and one-half inch albumen photograph that I purchased in an eBay auction, shown below. Images of U. S. Colored Troops, as they were officially designated, in such a grouping are themselves relatively rare, but what makes this image truly remarkable is that each soldier is identified on the pasteboard mount by a penciled notation, written in a very distinctive hand.

African American Union soldiers from L’Ouverture Hospital, in Alexandria, Virginia,

probably taken between early December 1864 to early April 1865. The men – a corporal,

eight infantryman, a drummer, and a fifer – appear to have been arrayed as an

Honor Escort for a deceased private. From left to right they are Tobias “Toby” Trout,

William DeGraff, John H. Johnson, Jerry Lyles (or Lisle), Leander Brown, Samuel Bond,

Robert Deyo, Adolphus Harp, Stephen Vance, George H. Smith, Adam Bentley, and

Reverend Chauncey Leonard. Private collection of Charles Joyce; used with permission. Click image to enlarge.

Close-up of the soldiers’ names, written by Francis Snow at the bottom of the mount.

Private collection of Charles Joyce; used with permission. Click image to enlarge.

The tools used to determine who these men were – and to posit a reason why this image was made in the first place and how it finally ended up in the personal effects of a University of Kansas Chancellor – were found chiefly in two repositories: The National Archives in Washington, D.C., and the Records of the Office of the Chancellor at Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

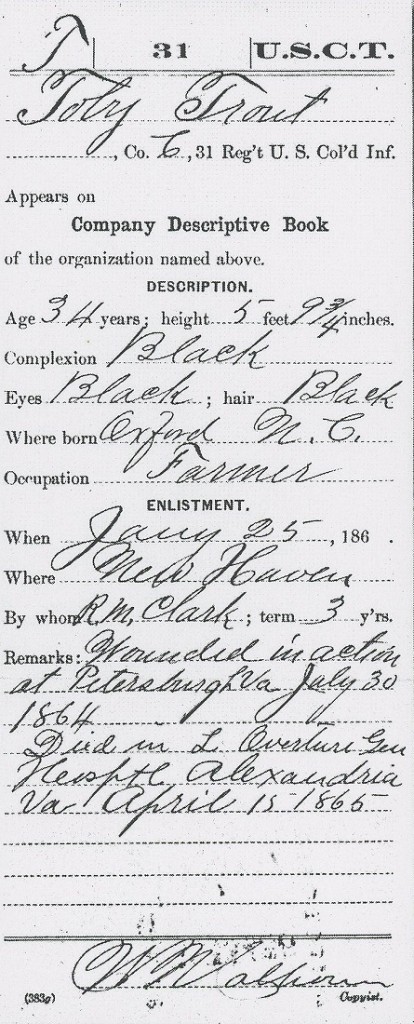

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation made the enlisting of black men into the Union Army a reality, and by the end of the Civil War roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Army) had served as soldiers, with another 19,000 having served in the Navy. The War Department created a Bureau of Colored Troops to oversee, in as orderly a fashion as possible, the induction and service of the black soldiers. Because of the Bureau, records kept of those men were both systematic and fairly scrupulous, as illustrated by the documents below. Moreover, soldiers who survived the fighting – especially if they had been wounded or ill during their service – usually filed for a federal pension. This process generated reams of additional bureaucratic paperwork. While undoubtedly maddening for the claimant, these records are invaluable to the modern-day researcher. Today, the service and pension records of the USCTs are mostly digitized and available using online pay-for-use services like Ancestry.com or Fold.com; copies of records can usually also be obtained for a fee by an online request or personal visit to the National Archives.

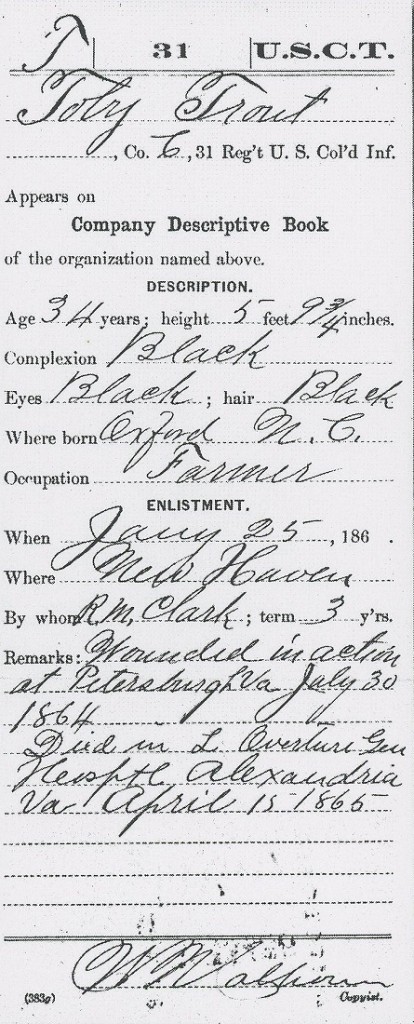

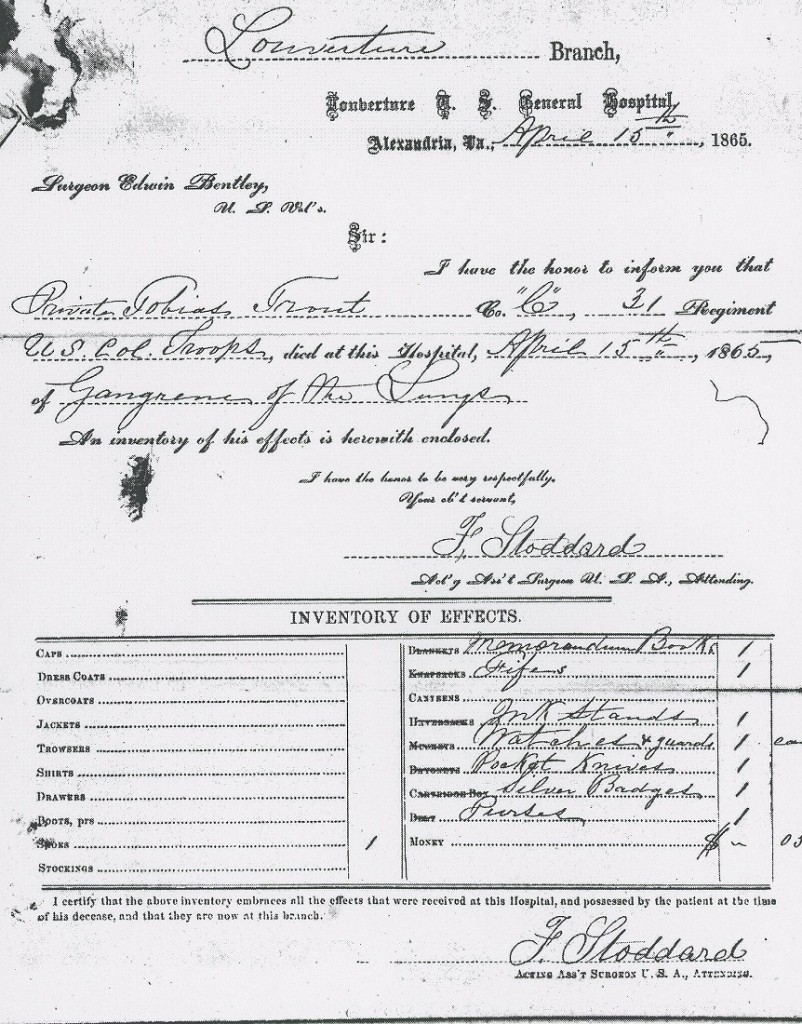

A page from Tobias (Toby) Trout’s service file.

Original document held by the National Archives and

Records Administration. Copy in the private collection of

Charles Joyce; used with permission. Click image to enlarge.

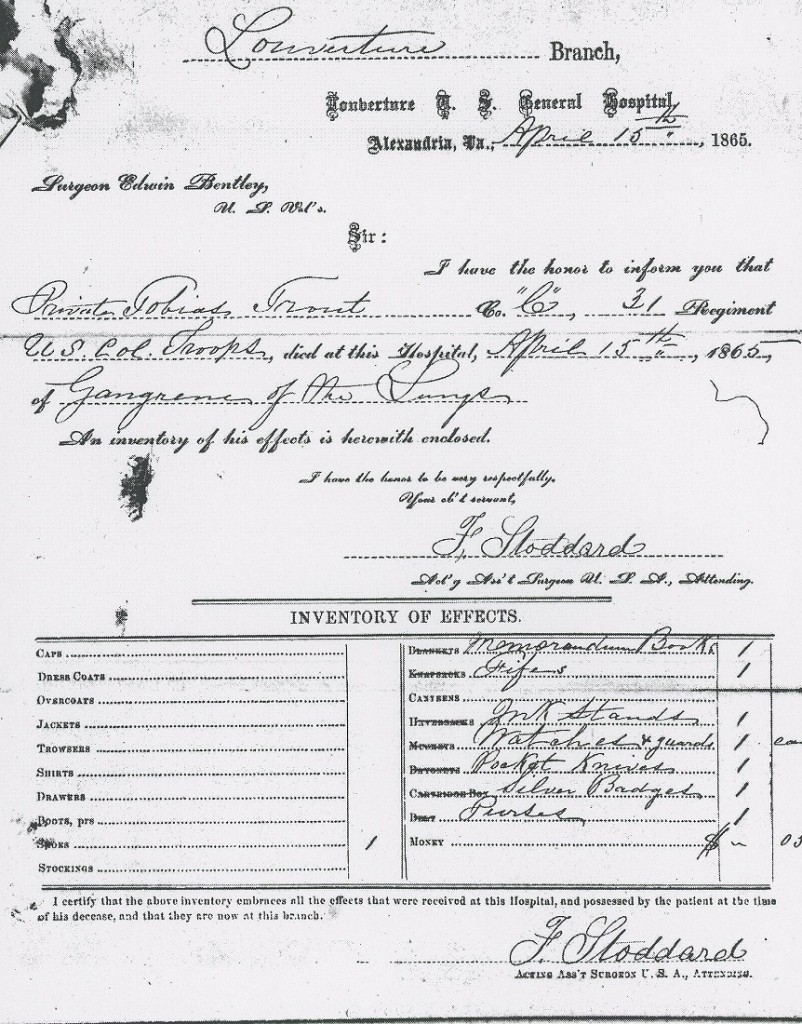

This document shows the belongings – or personal effects –

Toby Trout left behind when he died at L’Ouverture Hospital of

“gangrene of the lungs.” His effects included a fife, possibly the one

he’s holding in the photograph above. Original document held by

the National Archives and Records Administration. Copy in the private

collection of Charles Joyce; used with permission. Click image to enlarge.

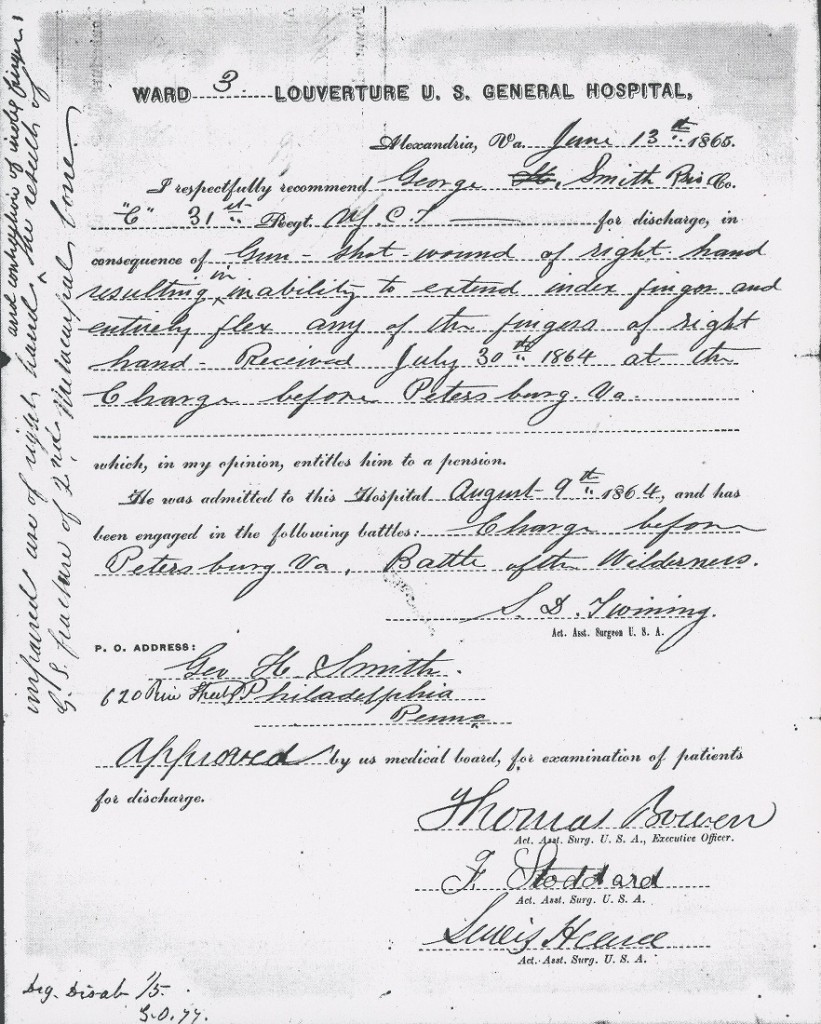

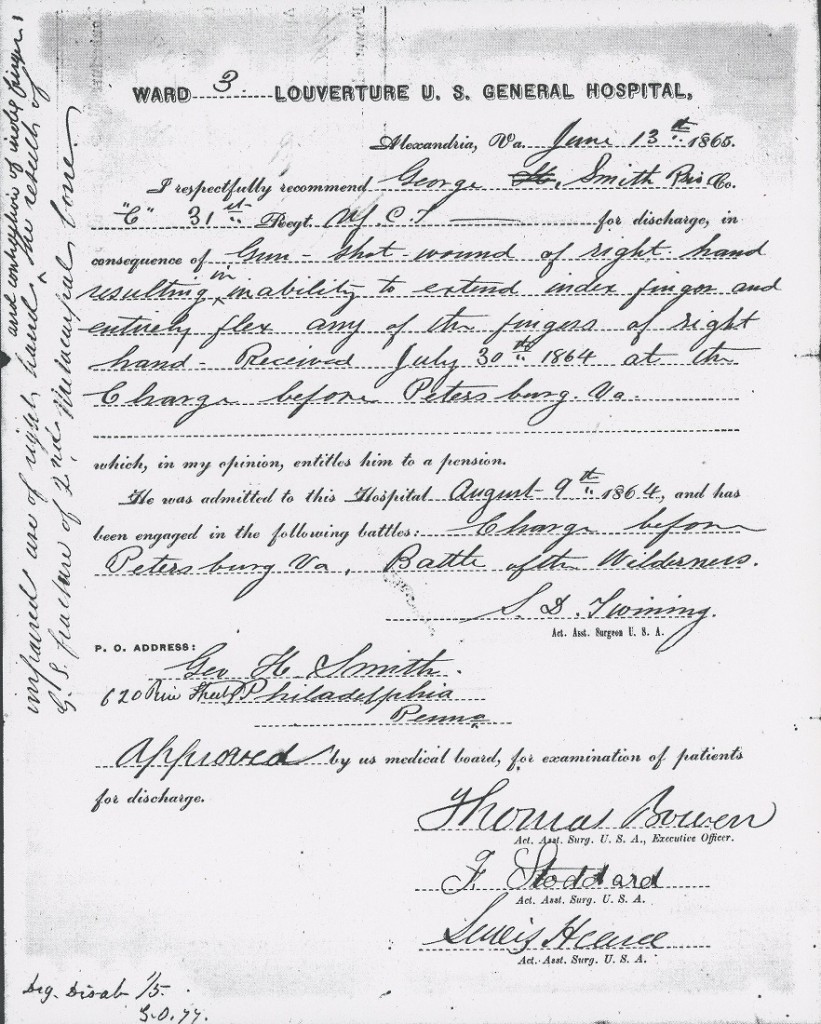

A page from George Smith’s service file, which describes a gunshot wound

to his right hand received at the Battle of the Crater. The injury disabled him for life and

can be seen in the photograph above. Original document held by the

National Archives and Records Administration. Copy in the private collection of

Charles Joyce; used with permission. Click image to enlarge.

My research into these records revealed that six of the soldiers in the photograph were wounded at the hellish Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. Encountering wounded soldiers from the battle, Francis Snow recorded in his diary on August 9th that “no visitor at L’Ouverture Hospital would for a moment cherish the shadow of a doubt concerning the bravery of the Negro troops on Sat. July 30th. The charge is utterly false that the battle was lost on account of their ‘cowardly behavior.’” The “calamity,” he insisted, was instead “due to some blunder on the part of officers high in command.”

The service and pension records of the men in the photograph also reveal telling details of their lives before the war. For example, Adolphus Harp had been flogged in the groin by his master with a rawhide whip when he was thirteen years old; fifty years later, he had to explain to pension doctors why the scar was still there. Robert Deyo was court-martialed for desertion (but acquitted) and Jerry Lyles (or Lisle) was similarly tried for breaking his musket over the head of one of his fellows during a drill. Wounded during the Crater fight, he was released from the hospital only to be readmitted some months later, now suffering from the effects of “secondary syphilis.”

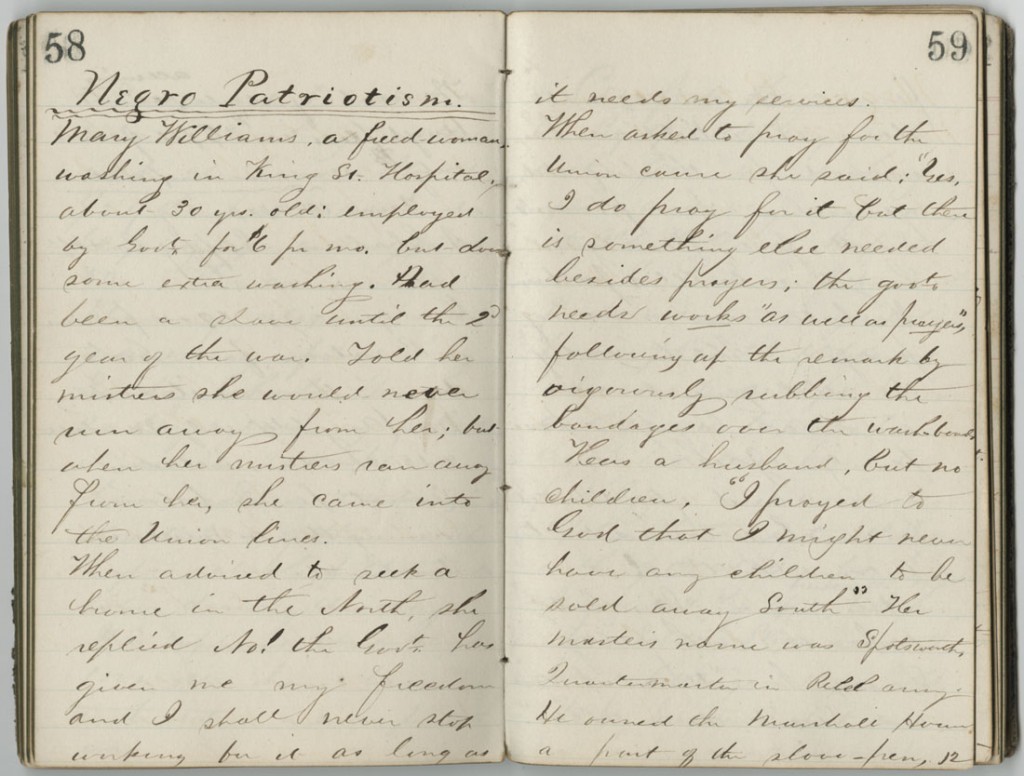

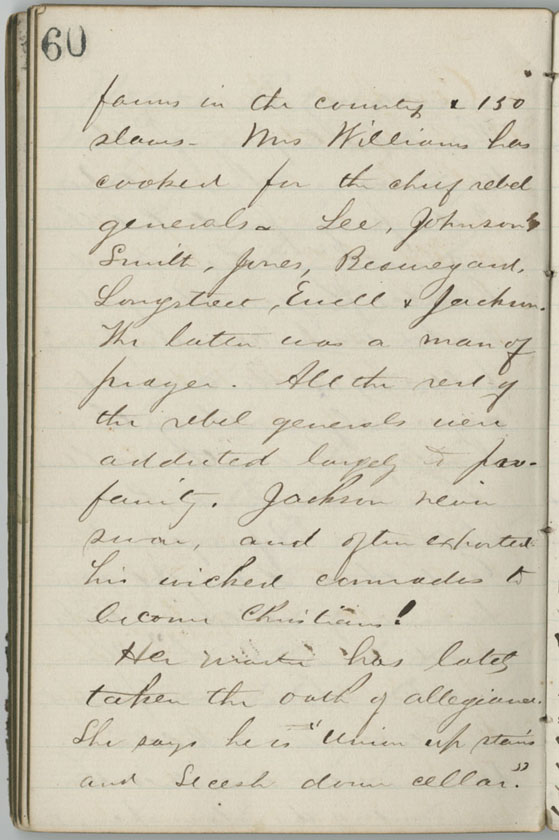

Service and pension records tell us this much, but it remains puzzling why the image was made and how it came to be found in Chancellor Snow’s private papers. Fortunately, KU’s University Archives at Spencer Research Library retains many of Snow’s letters, journals, and diaries of the Civil War period, including a memorandum book he kept as a Christian Commission delegate stationed at Alexandria. This established that one of his duties included ministering to the spiritual and physical needs of sick and wounded USCTs. And, while there is no account of him dealing directly with any of the men in the photograph – other than the Hospital’s Chaplain, Reverend Chauncey Leonard – Snow’s writings, including the examples shown below, are those of a young man who viewed African Americans as fully worthy of their freedom.

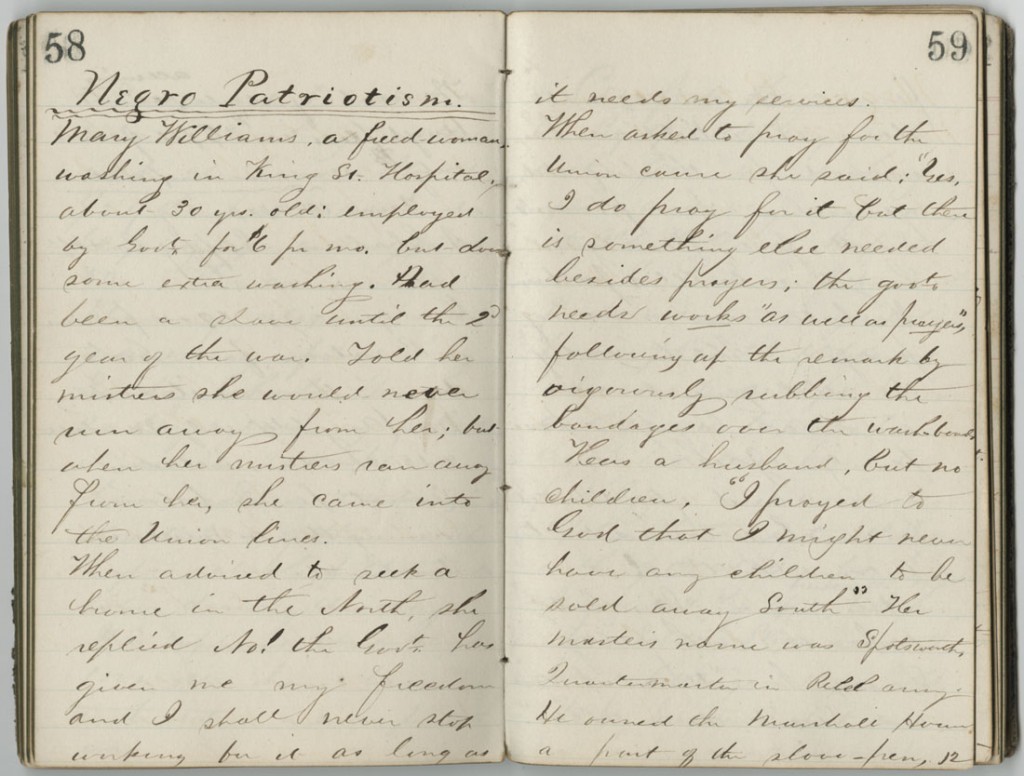

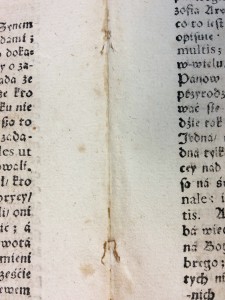

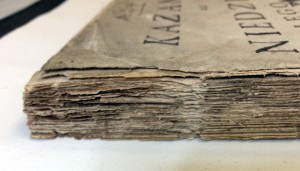

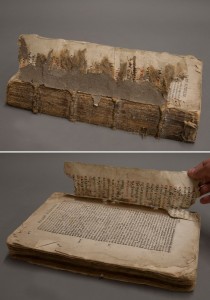

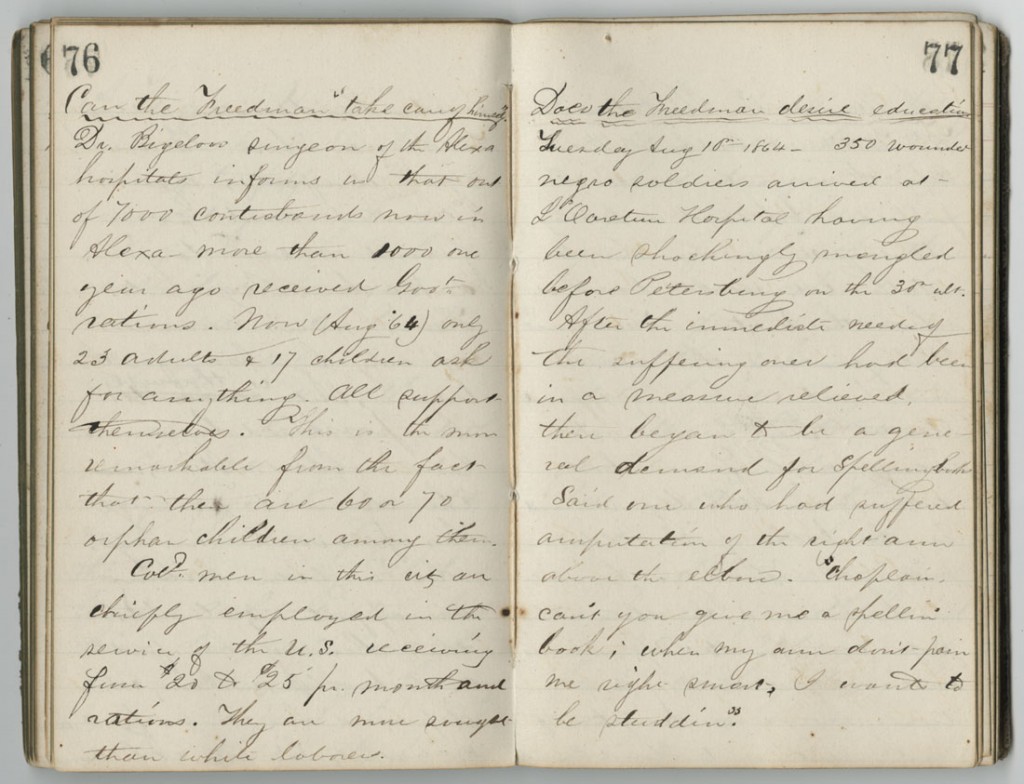

Some of Francis Snow’s thoughts and observations about African Americans

in the journal he kept while working for the U.S. Christian Commission

in Alexandria, 1864. University Archives. Call Number: RG 2/6/6. Click images to enlarge.

Plainly, Snow’s brief month-long sojourn affected him greatly. So, when an image was made of a group of black soldiers, Snow not only received a copy, but took the time to write each man’s name down – again in his own unmistakable hand – and kept the photograph for the rest of his days, until unearthed in another century, at a time when questions of race and justice nonetheless continue to confound us.

Charles Joyce

Guest Blogger and Spencer Researcher

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania