By 1969 American society was increasingly uncivil and the University of Kansas was facing a crisis. The struggle for civil rights and racial equality continued, but was joined by a radicalized white youth. They did not believe that American involvement in the Vietnam War was justifiable and had no interest in being drafted. Tension would remain high throughout the year, culminating in the so-called “Days of Rage” that included racial conflicts, student protests, bomb threats, arson, and sniper fire. This second and final part in a series about two of the most tumultuous years for the University outlines the events from May 1969 to May 1970.

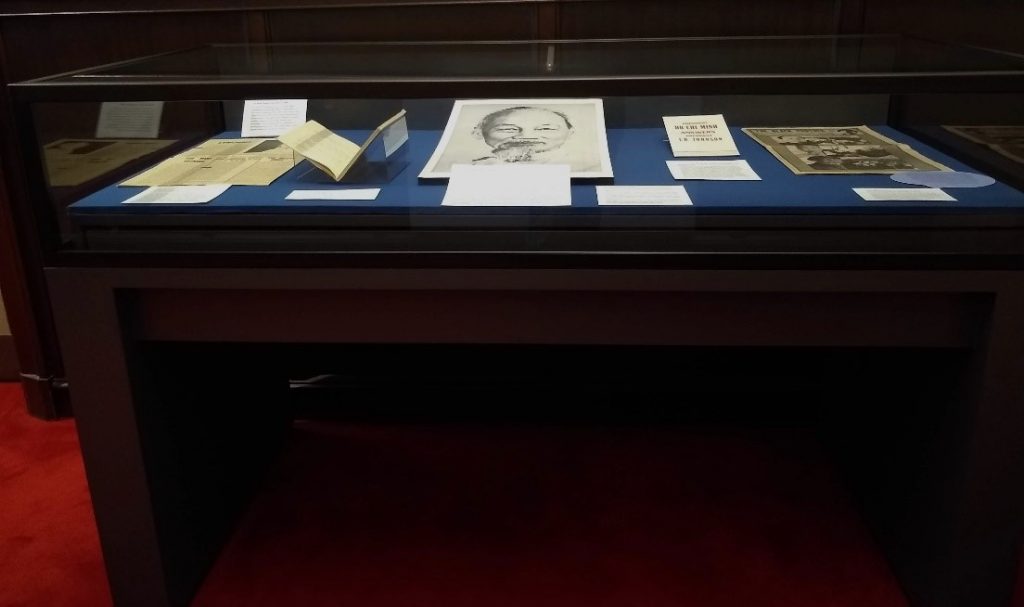

May 9, 1969: Protest Cancels ROTC Review

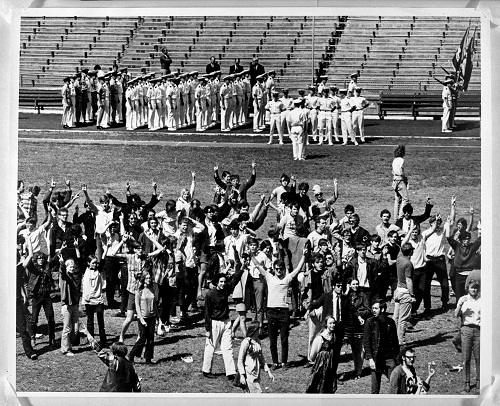

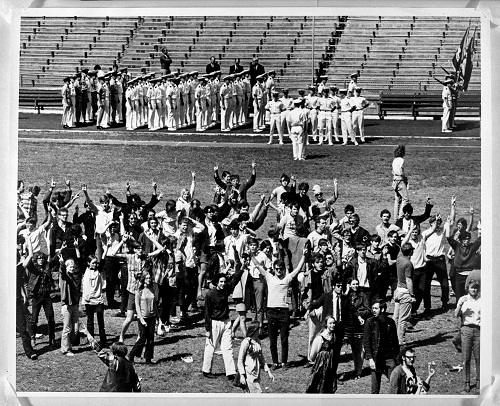

The annual Chancellor’s ROTC Review was cancelled when 200 protesters broke down the gate into Memorial Stadium. They began by reading the names of the 33,379 servicemen and women killed in Vietnam to date and then joined together on the field and started a sit-in, chanting and waving signs against the ROTC. Chancellor W. Clarke Wescoe decided the review could not be accomplished in such circumstances and wanted to avoid violence from the agitated crowd. The protest was organized by KU Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Afterward, 33 of 71 identified protestors were suspended for one semester by KU in confidential hearings. The event left Wescoe visibly drained and worried about what lay ahead; his fears would not be unfounded.

The group of protestors rallies in front of Strong Hall before their disruption

of the ROTC Review, May 1969. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 71/18 1969: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

Protestors during the ROTC Review at Memorial Stadium, May 9, 1969.

ROTC members stand on the track in the background. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 71/18 1969: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

October 15, 1969: National Vietnam Moratorium Day

More than 3,500 KU students, faculty, and locals paraded on Memorial Drive and Jayhawk Boulevard in protest of the Vietnam War. Later, about 150 people gathered in front of Strong Hall in a silent vigil held behind rows of white crosses. The day also included four KU professors making their case against the war inside Hoch Auditorium, attended by 3,000 students. Similar rallies and gatherings were happening all over the country, pressuring President Nixon to change policy in the Vietnam War.

Protestors lined up behind white crosses on the lawn of Strong Hall on

National Vietnam Moratorium Day, October 15, 1969. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 71/18 1969: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click images to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

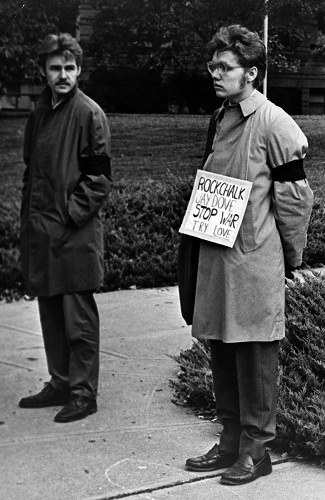

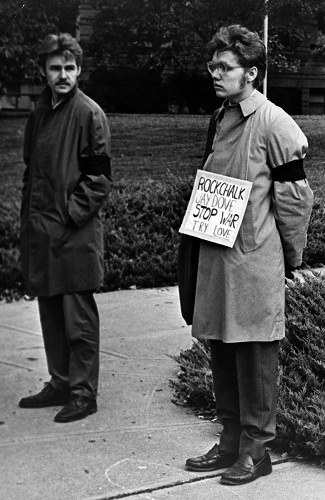

Two men silently protesting on campus,

National Vietnam Moratorium Day, October 15, 1969.

University Archives Photos. Call Number: RG 71/18 1969:

Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

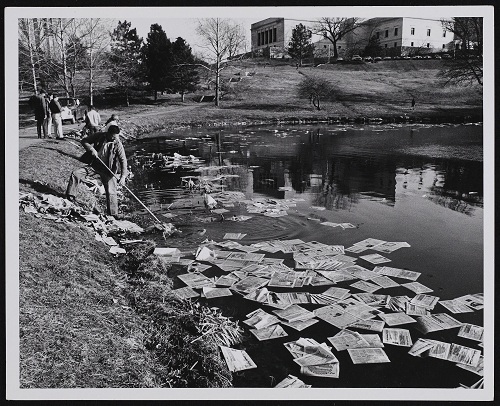

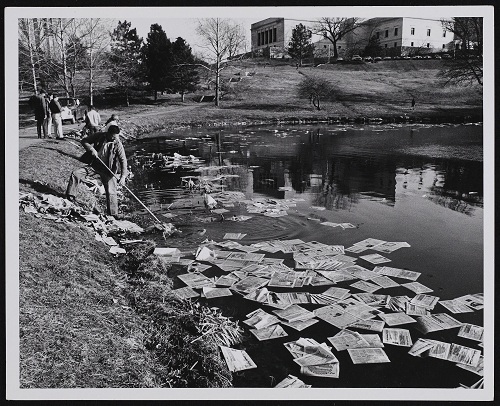

February 23, 1970: University Daily Kansan dumped into Potter Lake

In retaliation for the University printers’ decision to no longer print the Black Student Union’s (BSU) Harambee, the group gathered 6,000 copies of the UDK and tossed them into Potter Lake on campus. Harambee celebrated black culture and encouraged black solidarity. It ran information for a scholarship program established by BSU but also included Black Power Movement ideology, like the need for oppressed people to arm themselves to achieve freedom. The reaction from some white groups deemed the material obscene and inflammatory, leading to the printers’ decision to discontinue its service.

Black Student Union Protest, men pulling copies of the University Daily Kansan

out of Potter Pond, February 23, 1970. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 71/18 1970: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

February 26, 1970: Black Student Union Protest

The BSU presented a list of demands calling for more black faculty members and students and the creation of a black studies program. The timetable for the demands was deemed unrealistic by Chancellor Chalmers, but an African Studies program would be created later in the year.

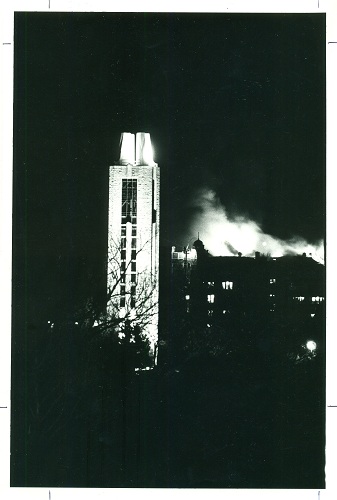

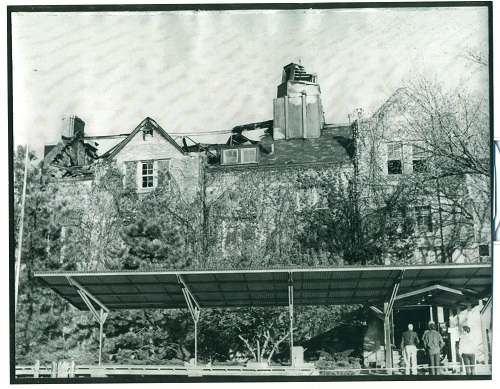

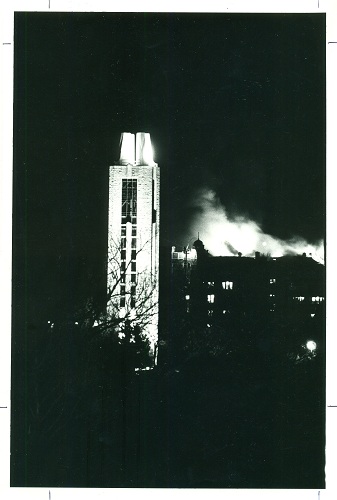

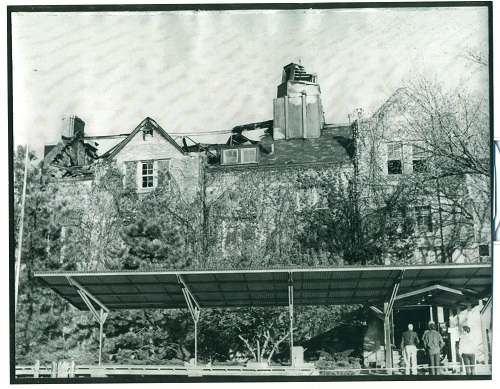

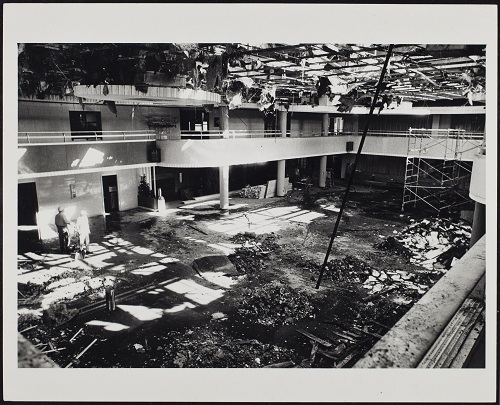

April 20, 1970: Arson Fire at Memorial Union

The culminating act in a day of mayhem and a week of civil disorder on the KU campus, a period often referred to as the “Days of Rage,” was the April 20, 1970, fire at the Kansas Union. Eventually deemed arson, the fire caused nearly a million dollars in damage and took place against the backdrop of a nation in turmoil over the Vietnam War and racial unrest in a college town considered a “hot bed” of political activism and protest.

Memorial Union fire, 1970. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 0/22/54/f 1970: Campus Buildings: Memorial Union (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

Memorial Union fire, exterior damage, 1970. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 0/22/54/f 1970: Campus Buildings: Memorial Union (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

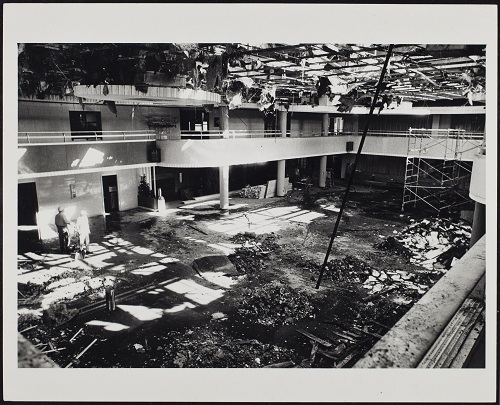

Memorial Union fire, interior damage, 1970. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 0/22/54/i 1970: Campus Buildings: Memorial Union (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

May 5-8, 1970

The month of May witnessed the greatest display of campus dissent and disorder. As the end of the 1970 school year approached, KU protesters urged fellow students to go on strike. After the US invasion of Cambodia and four student deaths at Kent State, the campus was on high alert.

May 5: A coffin-bearing crowd of 500 marches against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State massacre.

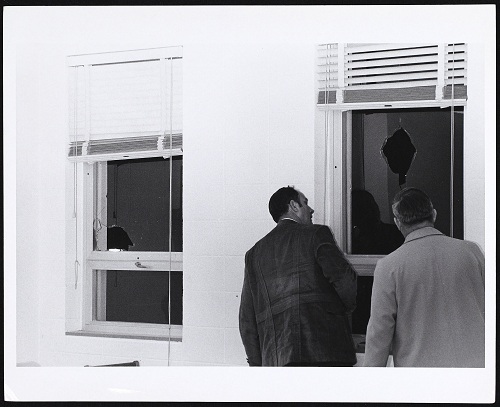

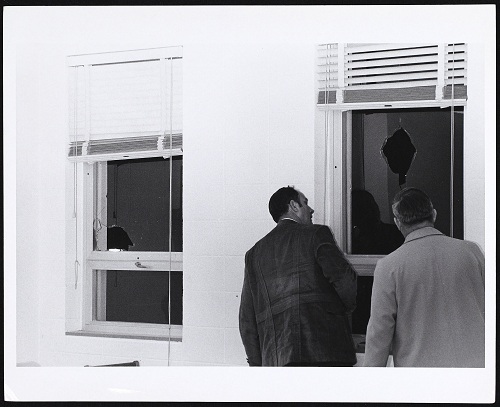

May 6: ROTC Review was cancelled for the second straight year as a crowd of 1,000 rallies against the group on campus. About 200 re-grouped and damaged the Military Science Building on campus.

Military Science Building, damage from student protests, May 7, 1970. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 71/18 1970: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

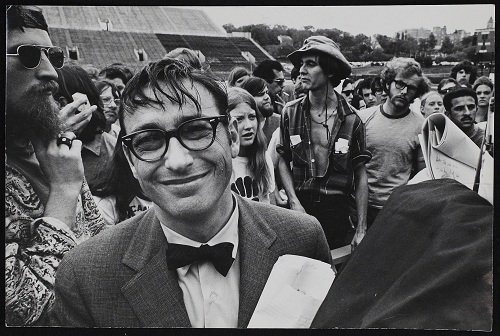

May 8: Chancellor E. Laurence Chalmers held an Alternative Convocation attended by 12,000 and allowed students to choose between finishing the semester in classes or completing the semester early and taking part in some political activity of their choice. Antiwar activists were upset the University did not take an official stand against the war and close down. Conservative politicians, regents, and alumni thought the Chancellor caved in to student radicals.

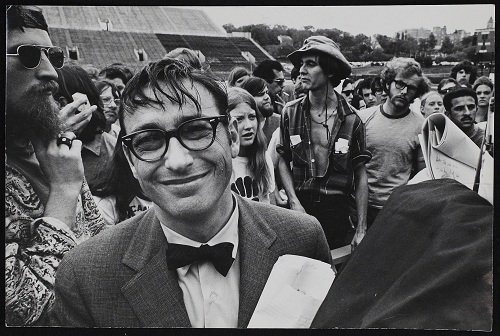

Chancellor Chalmers with students at Memorial Stadium for the

Alternative Convocation, May 8, 1970. University Archives Photos.

Call Number: RG 71/18 1970: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

Day of Alternatives, Chancellor Chalmers addressing students at Memorial Stadium, May 8, 1970.

University Archives Photos. Call Number: RG 71/18 1970: Student Activities: Student Protests (Photos).

Click image to enlarge (redirect to Spencer’s digital collections).

JoJo Palko

University Archives Intern