“Land of Opportunity: Nineteenth-Century Kansas,” a Short-Term Exhibit

November 20th, 2024This post was written by Tiffany McIntosh, who was Spencer’s Administrative Associate unit until last month. She is now the Outreach Manager at the Watkins Museum of History in downtown Lawrence.

This exhibit was developed over the last thirteen weeks as part of a final project for my master’s program in museum studies at the University of Oklahoma. To be able to graduate, I had the choice of doing a project, an internship, or a research paper. The choice of doing a project was fairly clear to me from the beginning. With guidance from an onsite supervisor, students were asked to find a museum (or similar institution) to work with to fill a need they had and to create a project that would further the student’s learning. Looking for some fun insights behind the process of curating an exhibit? Look no further!

How did the idea for this exhibit come about?

In order to graduate from my master’s program, I needed to do an independent project that I created in partnership with a cultural heritage institution. Having worked at Spencer, I felt it allowed me the opportunity to develop new skills in an environment I was already comfortable in. The project had to be outside our job scope which is why this was a great opportunity to learn new skills. Originally I was going to do an exhibit on a different topic, but my interest in the diaries in Spencer’s collections led me to the idea of Kansas in the 1800s. Knowing little about this topic, I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

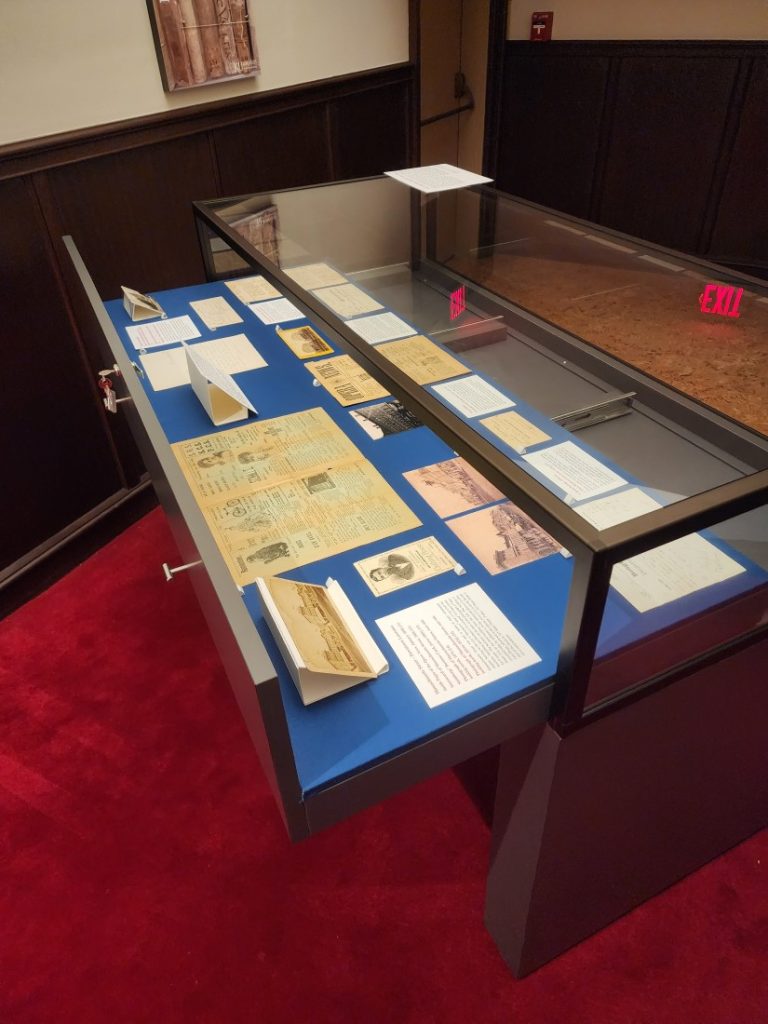

What was the process of creating the exhibit?

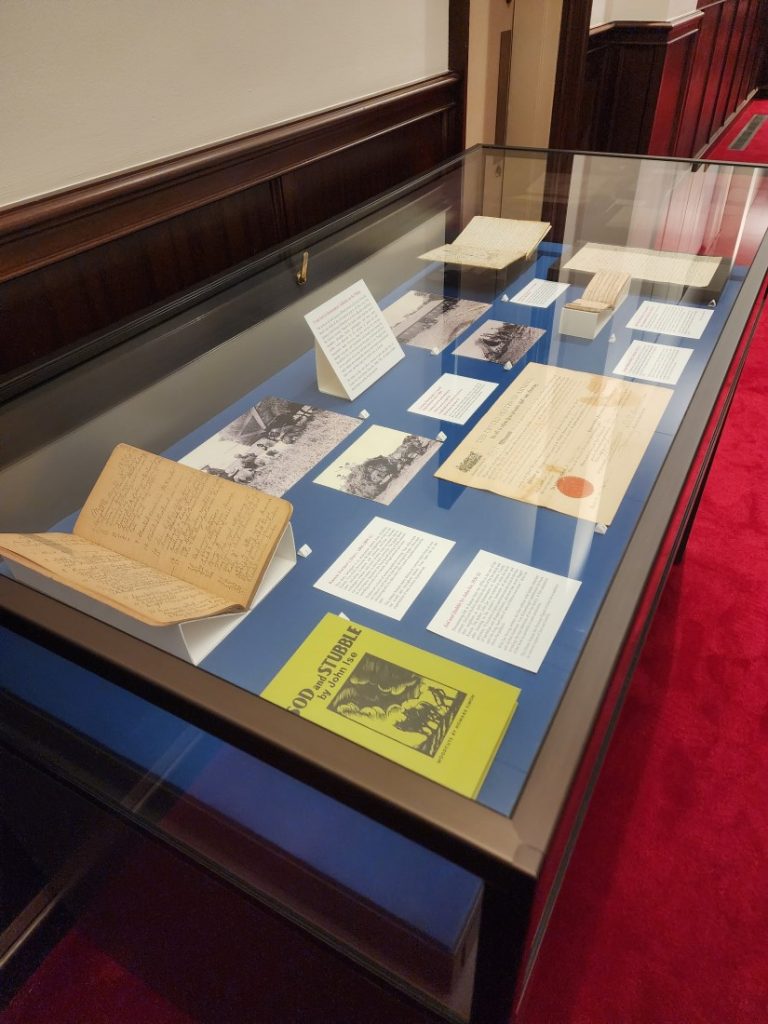

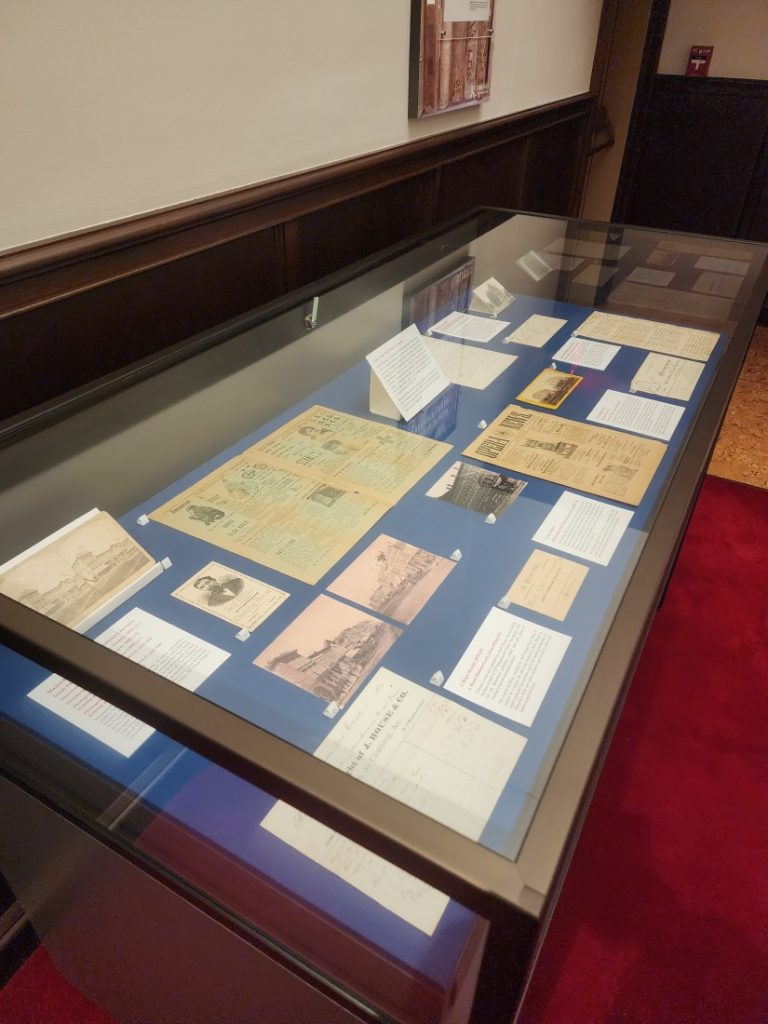

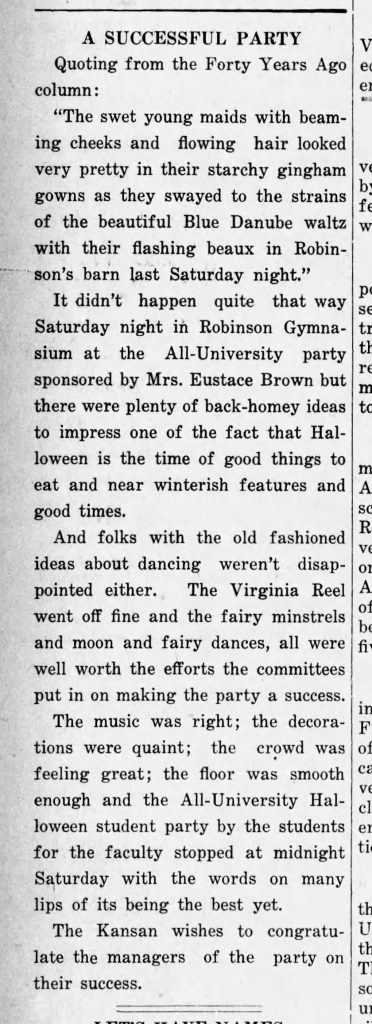

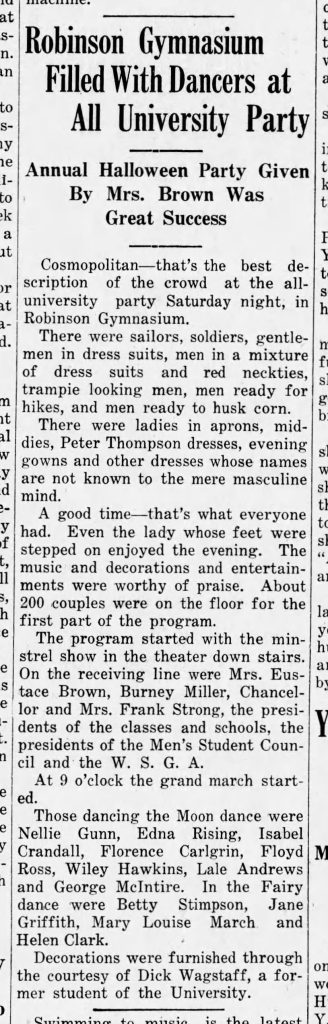

Once I came up with the idea and my project was approved, I started planning the direction I wanted to take. I began by digging through the finding aids and pulling collections to look through. I dug through over 115 collections before I found the right items for my exhibit. With the help of my onsite supervisor, Kansas Collection Curator Phil Cunningham, I was able to pin down layouts for my cases. Once my items and layouts were settled on, I scanned everything for my Omeka exhibit and sent them off to the conservation lab for treatment. After that I started the process of writing my exhibit labels. Writing labels was probably the hardest part of this whole process. There’s only so much you can portray in 100-200 words. Once my labels were ironed out, it was all just waiting for installation day. As I waited for installation, I wrote this blog post, created an activity, and worked on my Omeka exhibit.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered?

I would say I was most surprised by how hard it was to find things about rural life in the 1800s. There were plenty of ledgers, bank books, diaries (sometimes in illegible handwriting), and other things. But, there was a limited number of exhibit-worthy items that would get people thinking and talking. Finding photographs was the hardest. Every time I found one that I liked I would realize it was from the early 1900s. I suppose could have included those photos in the exhibit, but I was determined to stick to my plan.

What is the most interesting thing you learned while working on this exhibit?

I was pretty amazed that collections that have never been looked at together are interconnected. Many items in my case on Lawrence relate to each other but come from different collections. For example, I had previously worked with the J. House business card from the Lawrence business cards collection, so finding the J. House receipt in the Bowersock collection was super cool to me. It was also fun putting things into perspective. The exhibit includes a Steinbergs’ Clothing House business card, and one of the images I found has Steinbergs’ storefront in it. This might not seem cool on the surface level. When looking at the original photo you can’t read the business names. It wasn’t until I scanned and blew up the photo that I realized it showed Steinbergs’. I could go on forever but those were two of my favorite findings.

What do you hope visitors take away from this exhibit?

I hope viewers walk away with an understanding of how surprisingly different lives can be lived in a relatively close area. The author of the anonymous farmer’s diary talks about going to Kansas City, and imagining what that may have been like compared to life on the farm is just really interesting to me. I also hope people see the parallels of life in the 1800s to now. While there have been many advancements, rural farmers are still secluded from city life in a way while Massachusetts Street in Lawrence is still booming with business.

At the end of the day, this project has been a blast. I never thought I would be creating a physical exhibit as part of my program, one curated entirely by me at that. I have learned so many skills and things about my thought process throughout this semester. Things like the ups and downs of writing labels, or thinking you found the perfect item only to find it is in poor condition, or you can’t read it, or it does not fit the time frame. I hope visitors are able to feel some connection when they walk away from the exhibit.

Tiffany McIntosh

Spencer Public Services/Watkins Museum of History