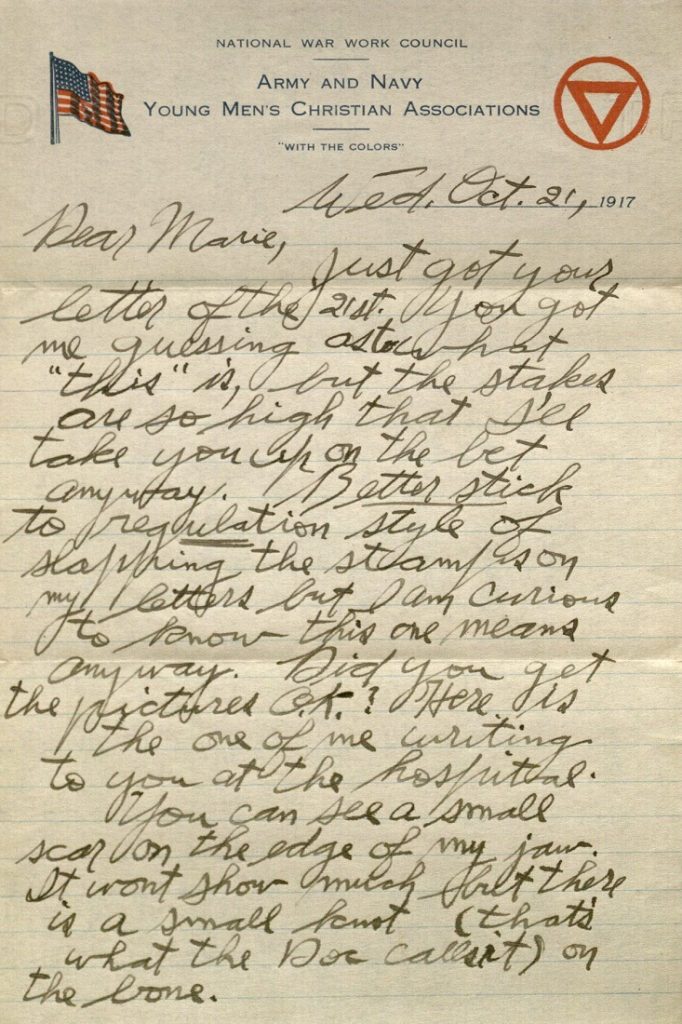

In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

Both of this week’s letters focus on Forrest’s “first taste of riding” a horse. “My horse certainly is a dandy,” Forrest tells Marie, “he knows his business to a dot. One trouble with him is that he shys [shies] at motorcycles, and once, when we were at a halt out in the hills, a cannon fired a salute back at the fort and I thought he jumped a foot.”

Click images to enlarge.

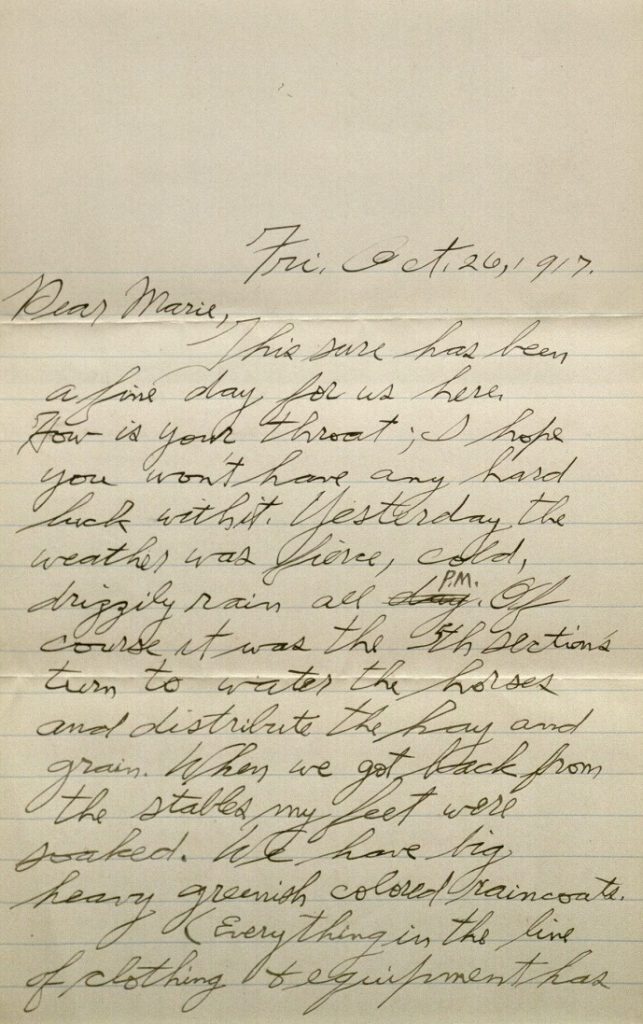

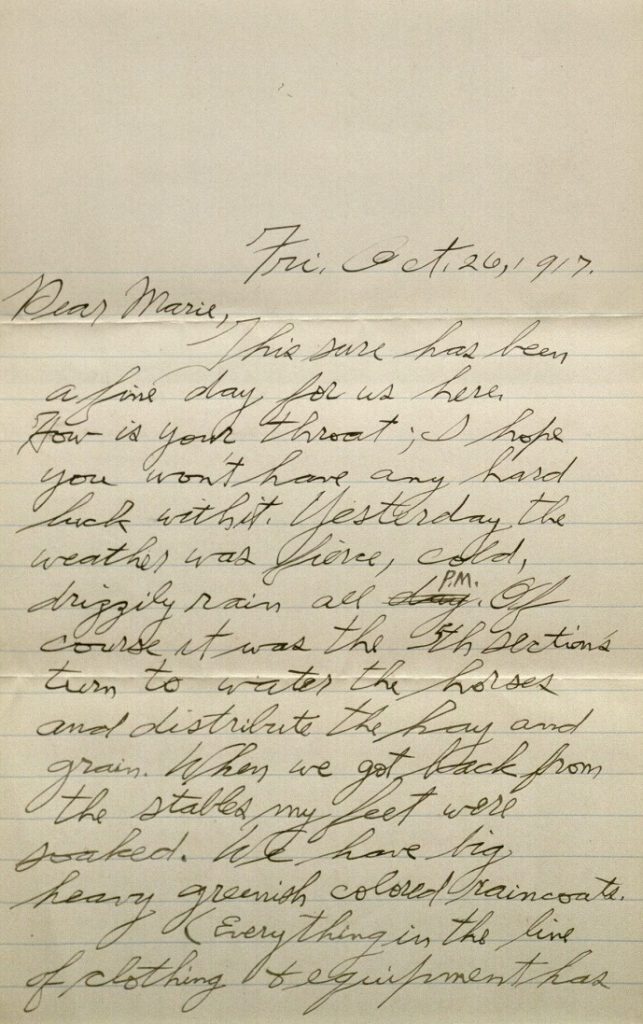

Fri. Oct. 26, 1917

Dear Marie,

This sure has been a fine day for us here. How is your throat; I hope you won’t have any hard luck with it. Yesterday the weather was fierce, cold, drizzly rain all P.M. Of course it was the 5th section’s turn to water the horses and distribute the hay and grain. When we got back from the stables my feet were soaked. We have big heavy greenish colored raincoats. (Everything in the line of clothing and equipment has that olive drab color and just matches the dead grass. A motorcycle sidecar in the field seems to blend into the background so you can hardly distinguish it.) Well – these raincoats have a very queer cut as they are intended for mounted service men. They are so long that they just miss touching the ground, and when buttoned single breasted they are a regular tent. The back is split clear to the waist.

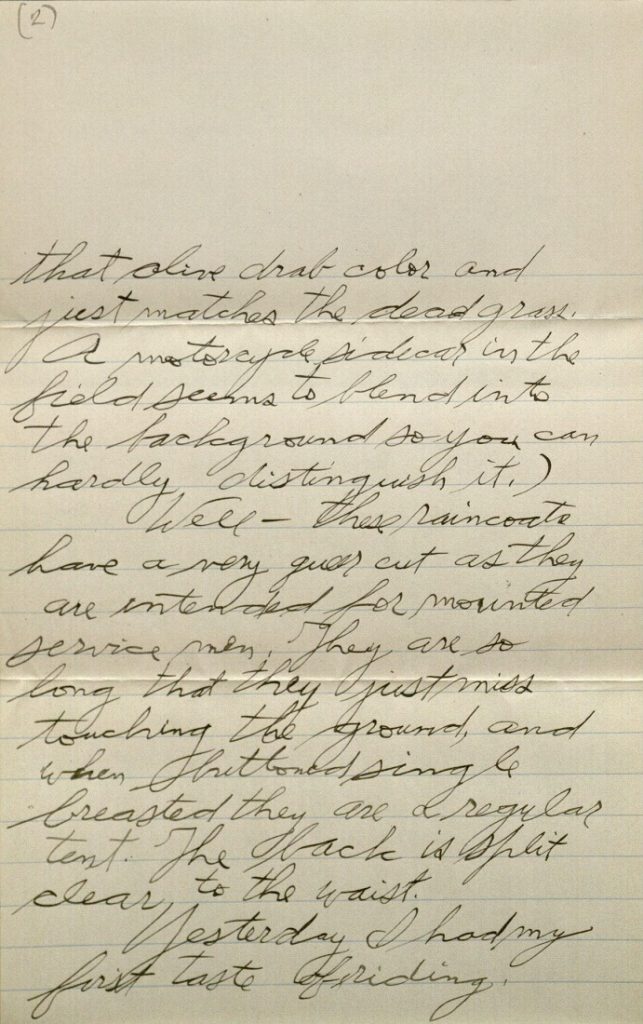

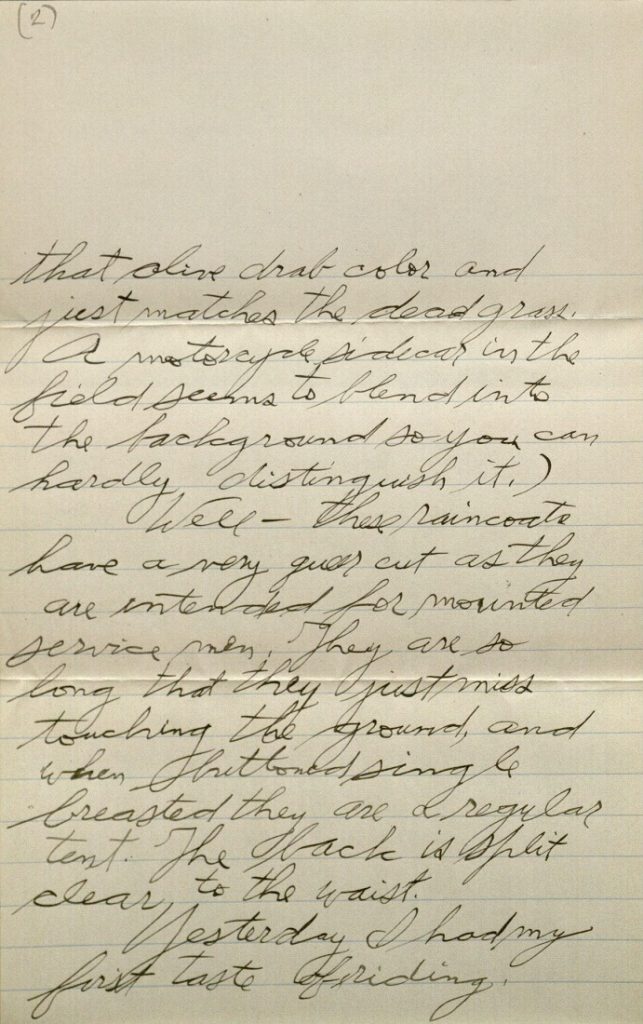

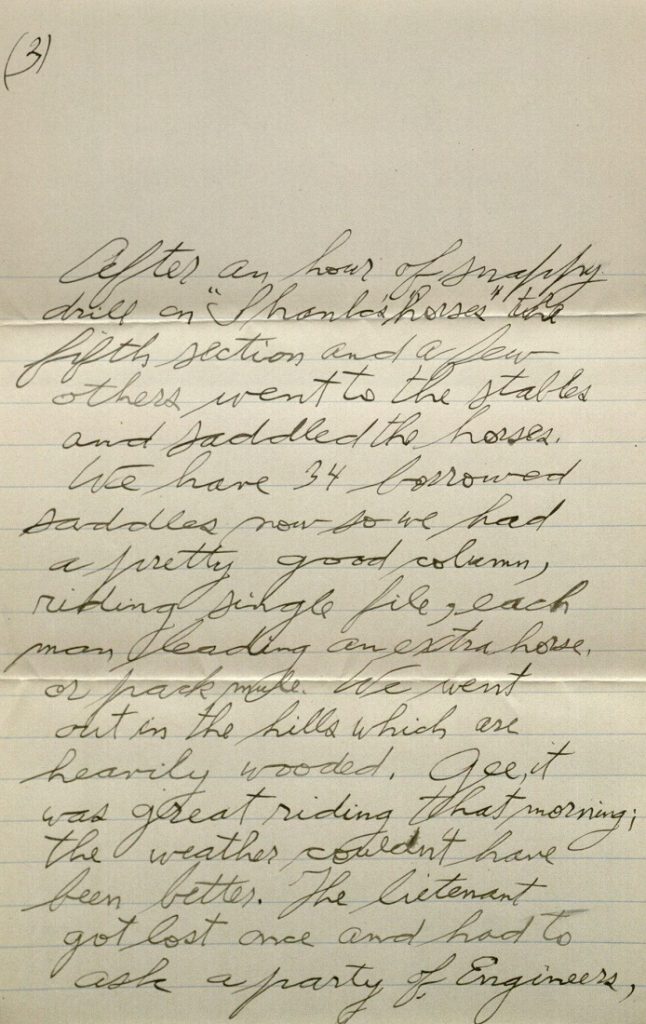

Yesterday I had my first taste of riding. After an hour of snappy drill on “Shank’s horses” the fifth section and a few others went to the stables and saddled the horses. We have 34 borrowed saddles now so we had a pretty good column, riding single file, each man leading an extra horse or pack mule. We went out in the hills which are heavily wooded. Gee, it was great riding that morning; the weather couldn’t have been better. The lietenant got lost once and had to ask a party of Engineers, who were out making maps, the right road in. We went about five miles altogether, half of it on a good trot, and got in about 11:00 A.M.

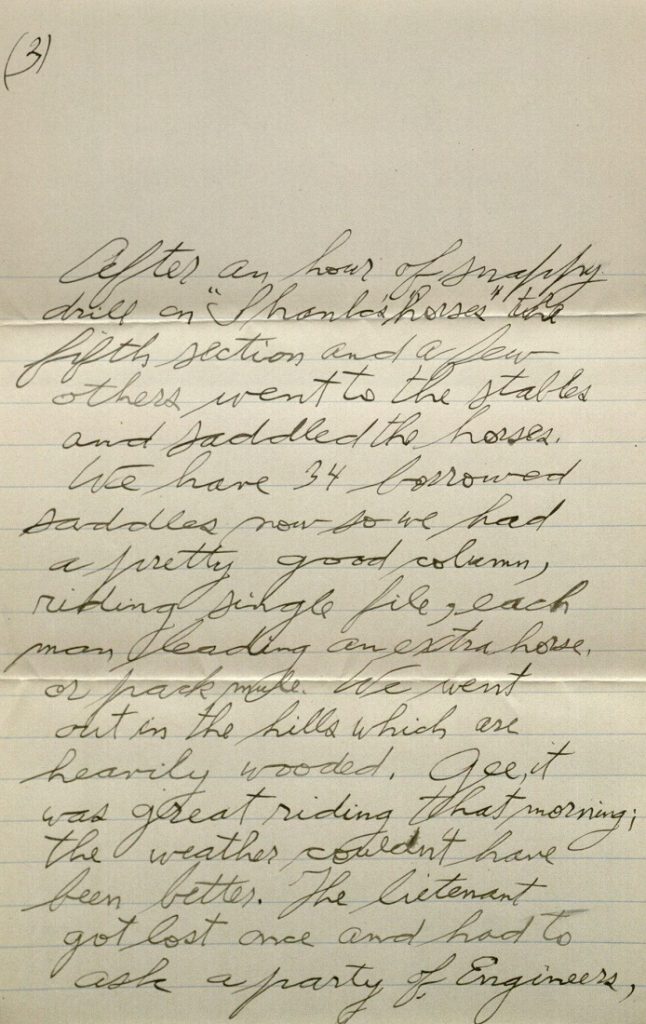

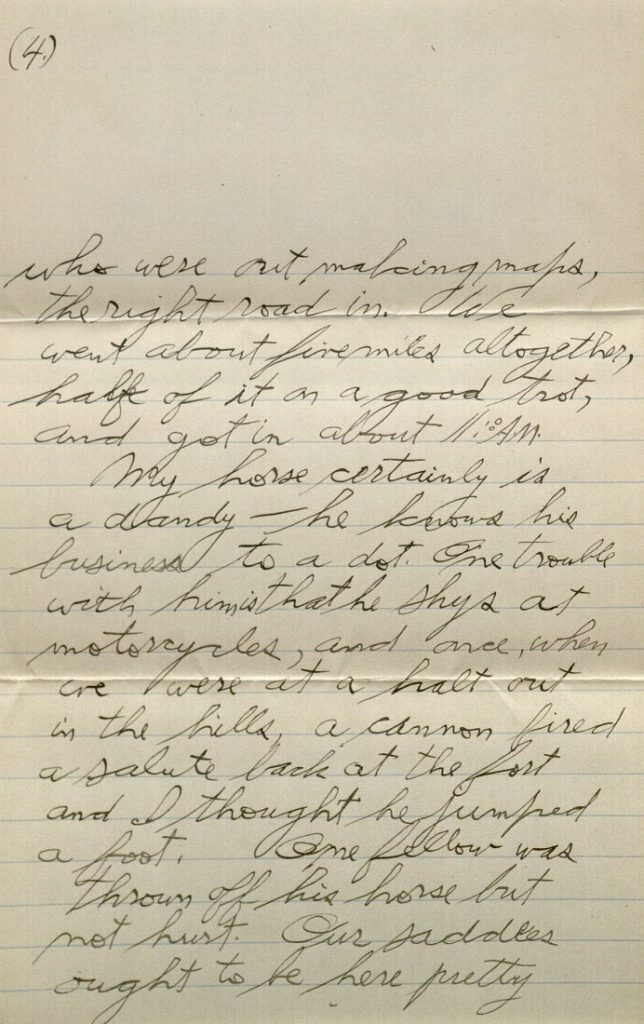

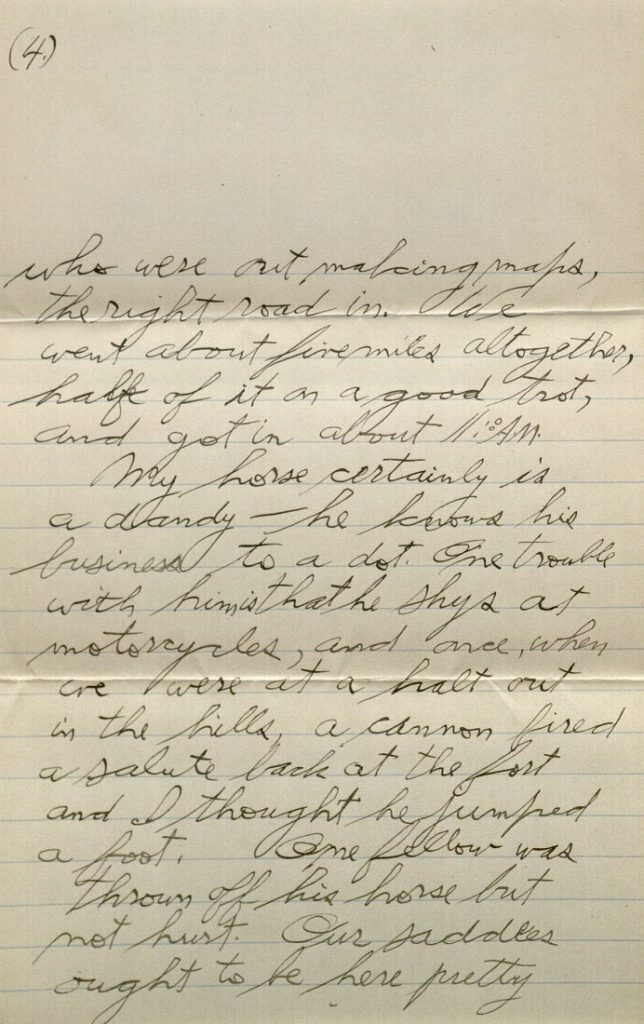

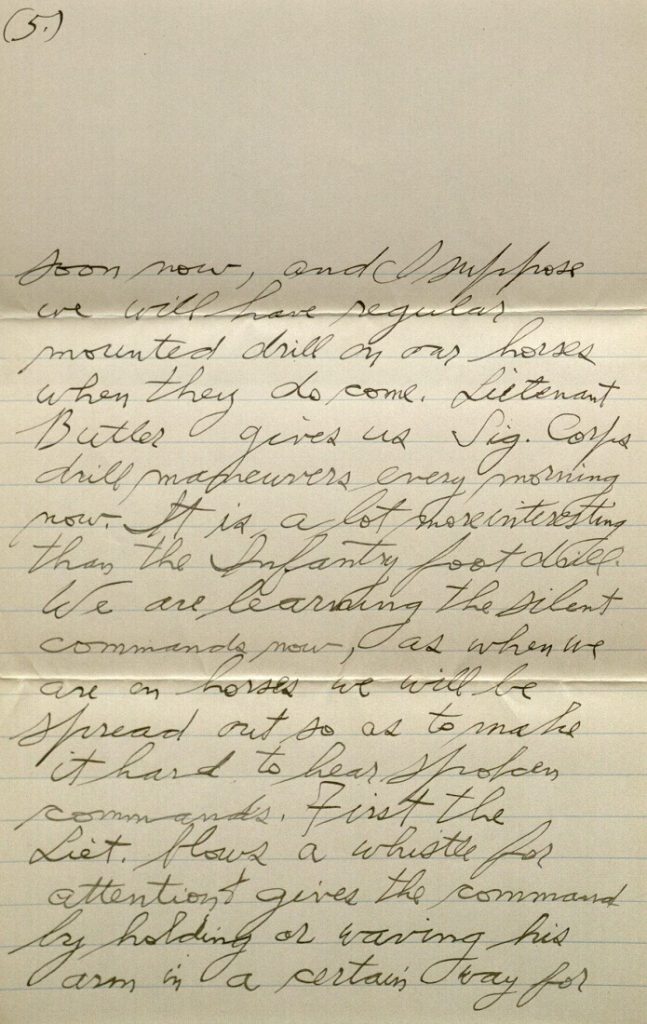

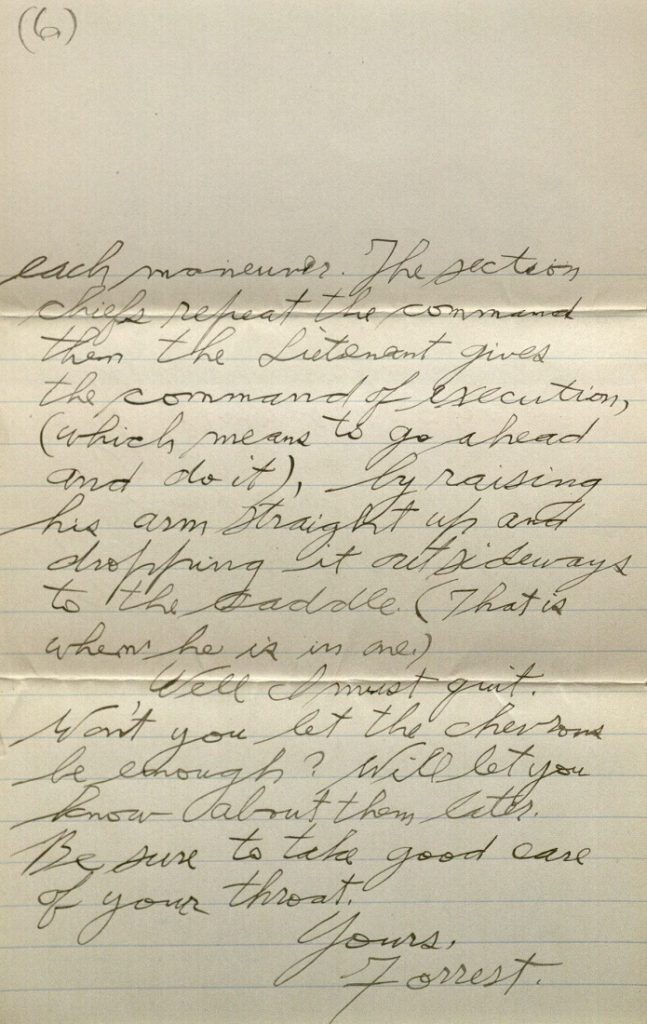

My horse certainly is a dandy – he knows his business to a dot. One trouble with him is that he shys at motorcycles, and once, when we were at a halt out in the hills, a cannon fired a salute back at the fort and I thought he jumped a foot. One fellow was thrown off his horse but not hurt. Our saddles ought to be here pretty soon now, and I suppose we will have regular mounted drill on our horses when they do come. Lietenant Butler gives us Sig. Corps drill maneuvers every morning now. It is a lot more interesting than the Infantry foot drill. We are learning the silent commands now, as when we are on horses we will be spread out so as to make it hard to hear spoken commands. First the Liet. blows a whistle for attention and gives the command by holding or waving his arm in a certain way for each maneuver. The section chiefs repeat the command then the Lietenant gives the command of execution, (which means to go ahead and do it), by raising his arm straight up and dropping it out sideways to the saddle. (That is when he is in one.)

Well I must quit. Won’t you let the chevrons be enough? Will let you know about them later. Be sure to take good care of your throat.

Yours,

Forrest.

Here is a picture of a couple of the fellows. Sgt. Brown is the chief of the fourth section.

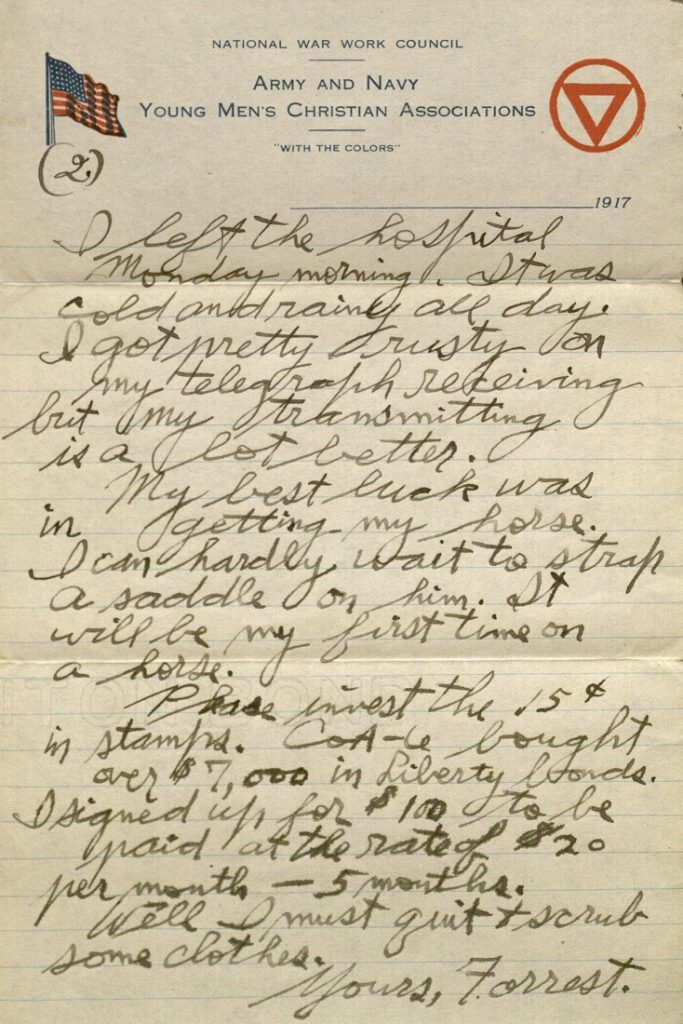

Sunday, Oct. 28, 1917.

Dear Marie,

Just finished the hardest days work I seen for a month. My turn at stable police came today after I had planned to do a lot of picture work. Jerry Berry and I worked steady from breakfast till 11:00 then I saddled my horse and went to the barracks (a short mile) for an early dinner. This was only the second time I had been on a horse, and the first time alone, so had to watch my step. The most trouble I had was when we passed motorcycles and autos. He’s no city bred horse by a long shot and sure does hate those little three wheeled buzz wagons. When we came near an auto he slowed down from a trot to a walk and as the auto passed he laid back his ears and stopped short. We sure had some dinner. Pork-chops, sweet potatoes, mashed potatoes, cabbage, bread pudding, and cocoa. I guess Tom was hungry too, for, on the way back, when he caught sight of the stables, he lit out on a gallop. This is easier riding than a trot so I let him go to it. I am mighty glad we have horses, for the riding is sure great stuff. We are allowed mounted passes from 1:00 P.M. to 4:00 on Sunday. When I got back the other fellows went to dinner. At 1:30 we bedded the stalls and put out the hay and grain. I took a few pictures and then it was time for me to go to supper, so as to get back before regular mess.

Say, would your Mother let you use my .25 cal. automatic? If you want to shoot, and your folks don’t object, you’re welcome to it. Of course the gun has to be thoroughly cleaned right after using, and I will have to show you how to take it apart and remove the barrel.

Don’t you think it would be better if you did go to these parties even if you don’t care very much about them? I wish you would – I don’t like to hear of people noticing that you only go with me. Please don’t misunderstand me – I simply think you out to go just for that one reason, don’t you?

I can’t get the goods nor the fine olive drab silk floss for the chevrons so will have to give it up. Here are some cards.

Yours,

Forrest.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant