Recent Acquisition: The Facts Behind the 1970 Police Shooting of a KU Student

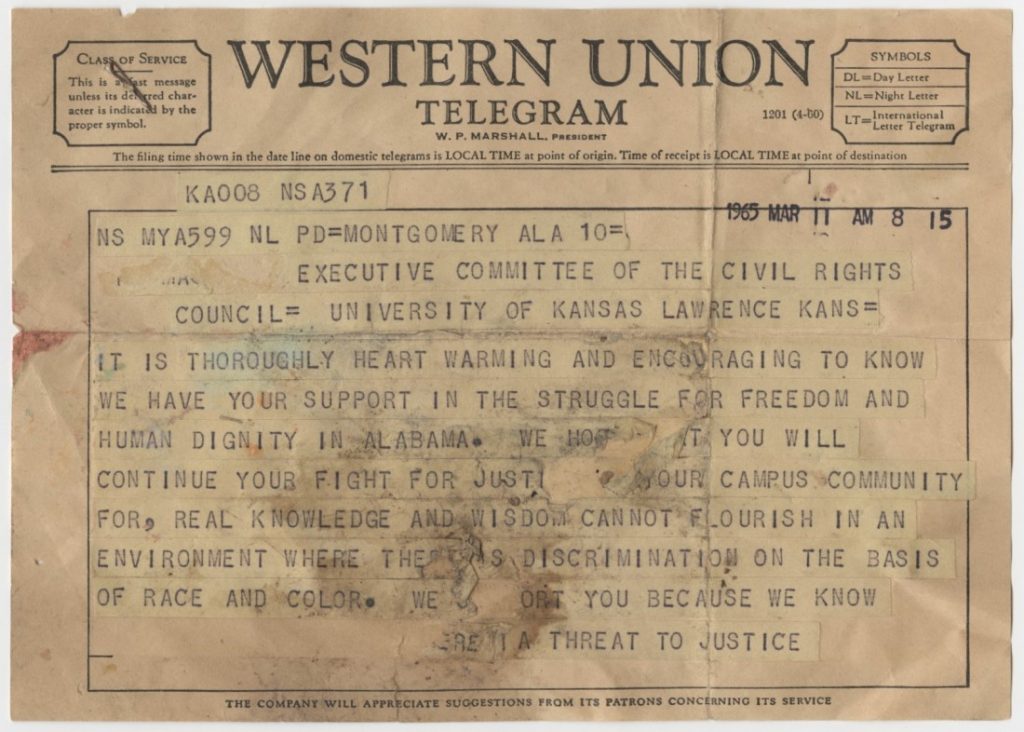

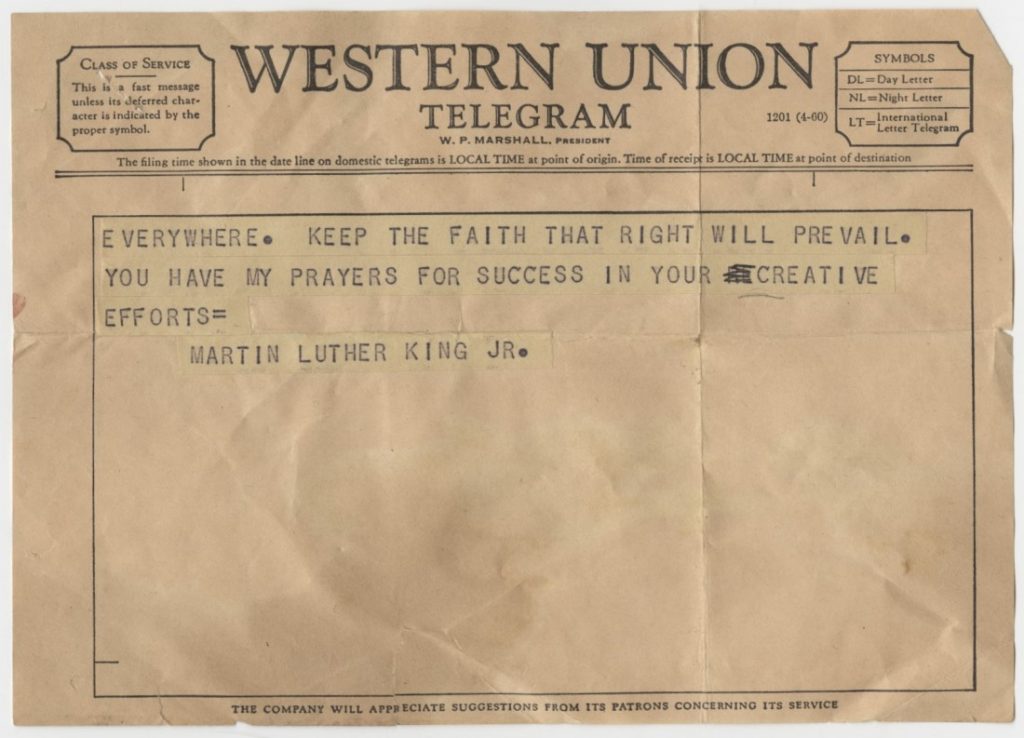

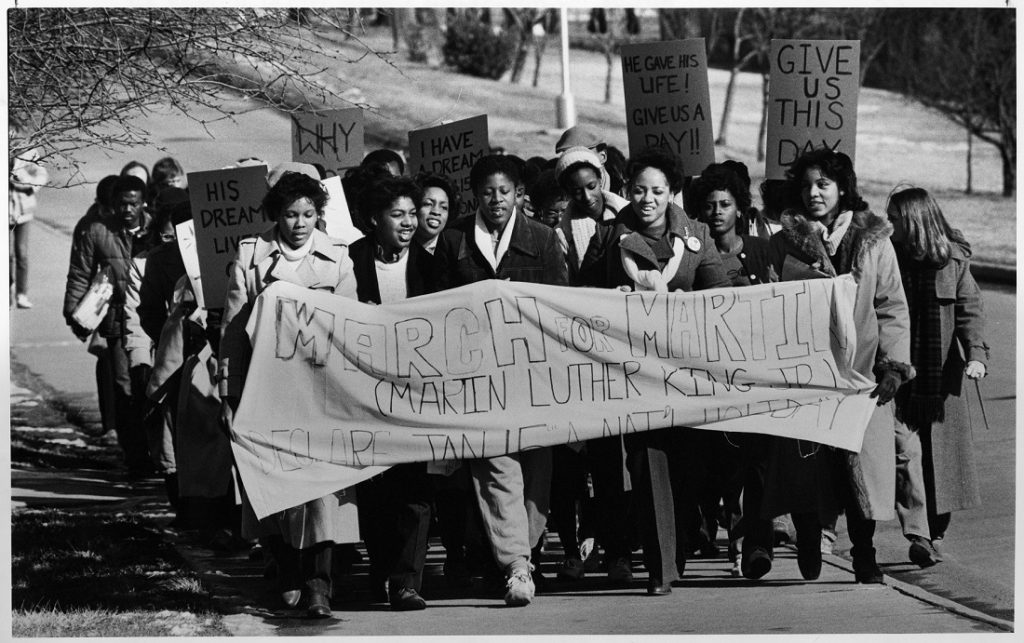

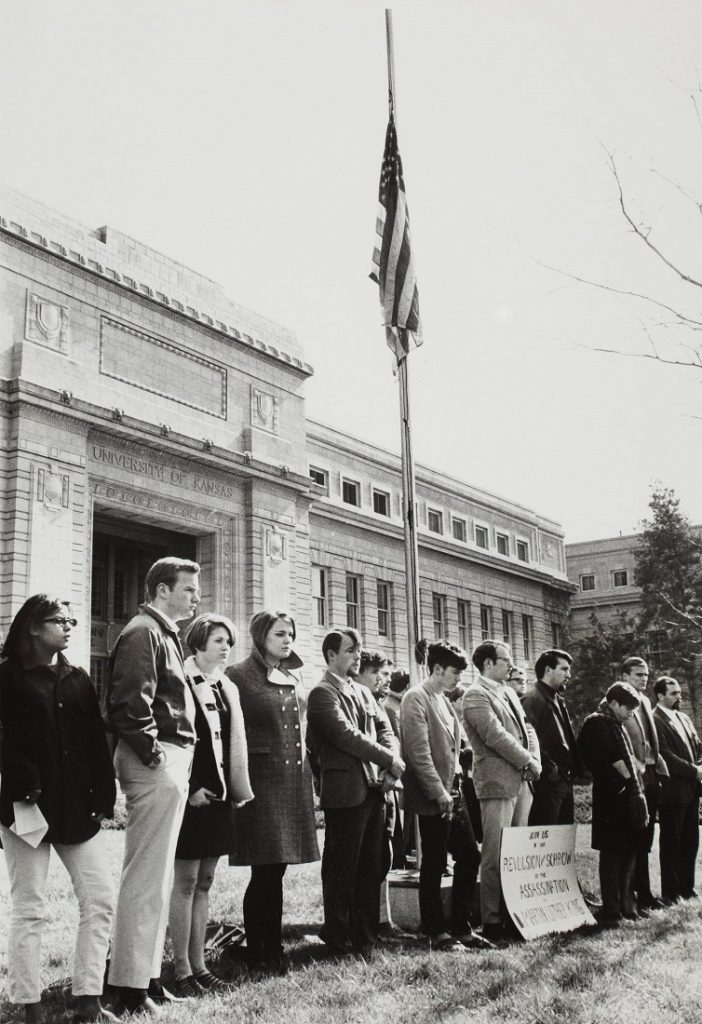

July 19th, 2023In 1970, the United States was deeply divided along social, racial, economic, generational, and political lines. Young people across the country were protesting in favor of civil rights action and against the Vietnam War and military recruiting on college campuses. That spring the National Guard killed four student protesters at Kent State University. While the incident at Kent State holds a place in the national consciousness, many are unaware that there were two shootings near the University of Kansas (KU) that summer.

Later dubbed the Days of Rage, pipe bombs, dumpster fires, and sniper fire were not uncommon in Lawrence, Kansas, during the summer of 1970. Arsonists burned the KU Union in the spring. The lethal violence began when Lawrence Police Officer William Garrett killed former KU student and Black Student Union activist Rick “Tiger” Dowdell on July 16, 1970. During protests in response to the police shooting, police shot and killed KU student Nick Rice on July 20.

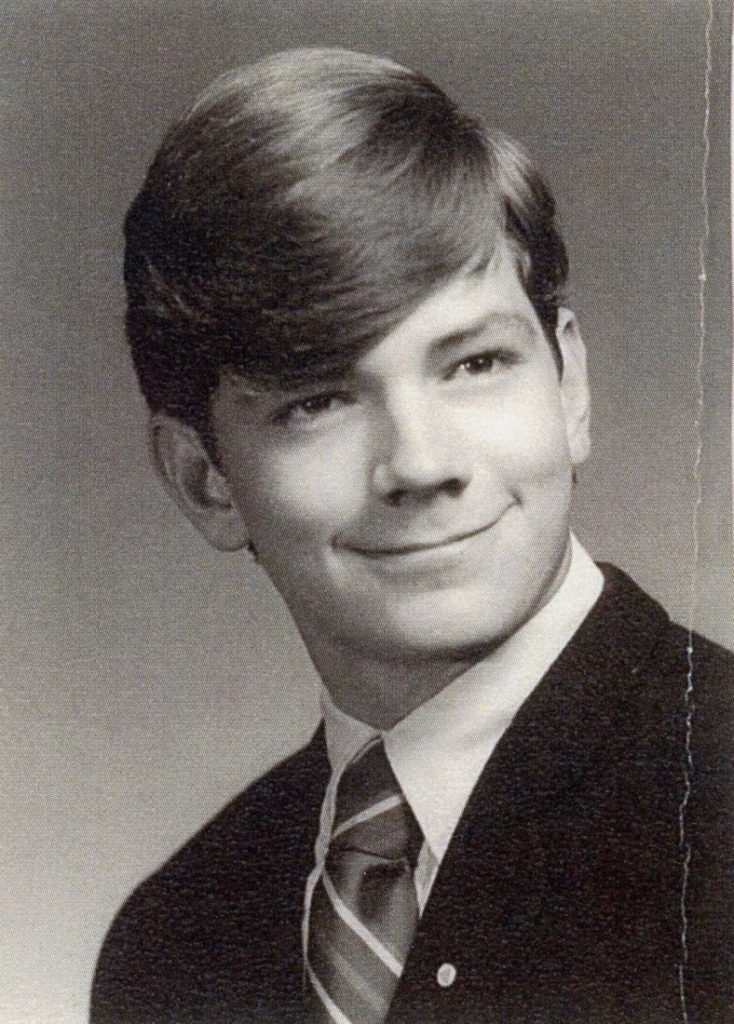

According to a newspaper interview of a fellow member of the Zeta Beta Tau Fraternity, Nick Rice supported civil rights and was against the war, but he was not a protestor. He was one of the students who helped to put out the fire in the Union and received a commendation from the city of Lawrence for his bravery.

The night that a city officer shot him, Rice was with his girlfriend and friends playing pinball at the Rock Chalk Cafe while protesters gathered outside. Officers were throwing teargas as Rice and his friends were leaving. One protester tried to start a car on fire but was unsuccessful. Police fired at the short, long-haired, would-be arsonist and hit tall, clean-cut Rice in the back of the head. Officers continued to throw teargas as bystanders attempted first aid.

No one was ever charged for killing Nick Rice or Tiger Dowdell. An all-white coroner’s inquest found that Lawrence Police Officer William Garrett did not have felonious intent when he killed Tiger Dowdell. The official statements released by the Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI) and at Rice’s inquest claimed “insufficient evidence” of wrongdoing in the shooting of Nick Rice. However, the KBI files in the newly-processed Personal Papers of Harry Nicholas Rice (Call Number: PP 647) tell a different story.

The Lawrence Times had access to the lightly redacted KBI Nick Rice case files before they were donated to Spencer. In 2021, they published a series of articles on the Nick Rice case based on these files, suggesting an intentional cover up of the evidence.

The KBI summary of the incident, submitted in August 1970, makes it clear that Officer Jimmy Joe Stroud thought he shot someone and Lawrence Police Officer Virgil Foust found a bullet from Officer Stroud’s gun near the site where Nick Rice fell. Foust gave the bullet to Police Captain Merle McClure, who put the evidence in his pocket and took it home, breaking the legal chain of custody and causing the “insufficient evidence” of wrongdoing. Captain McClure did not turn over the evidence until the KBI investigators asked him specifically if he had the bullet. Neither the KBI nor the Lawrence Police Department shared this information with the public or with Rice’s family.

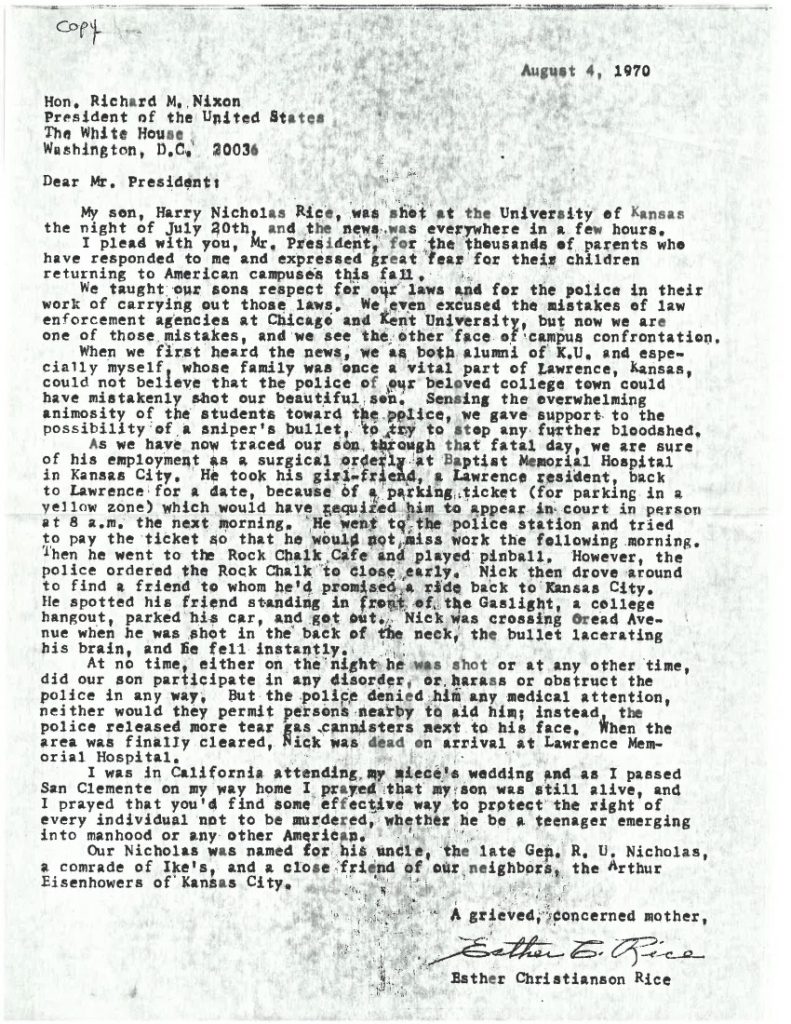

Nick’s mother, Esther Rice, was a supporter of President Richard Nixon. She wrote to the President, asking him to end the kind of violence that caused the death of her son, an innocent bystander at a protest.

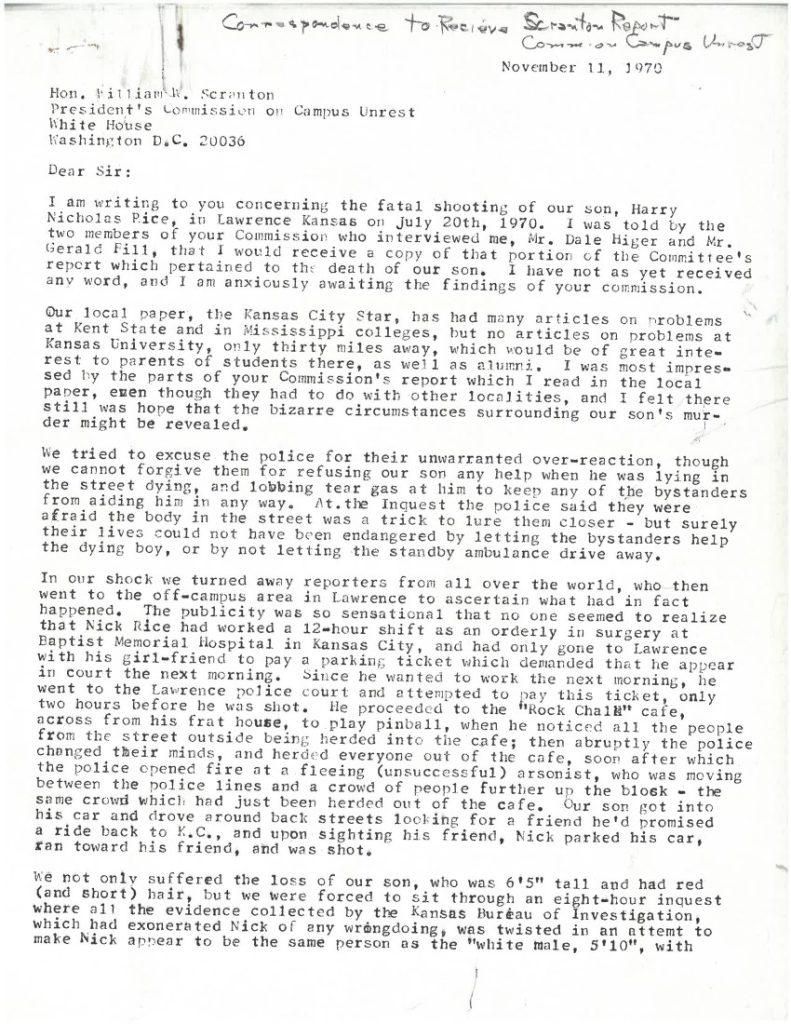

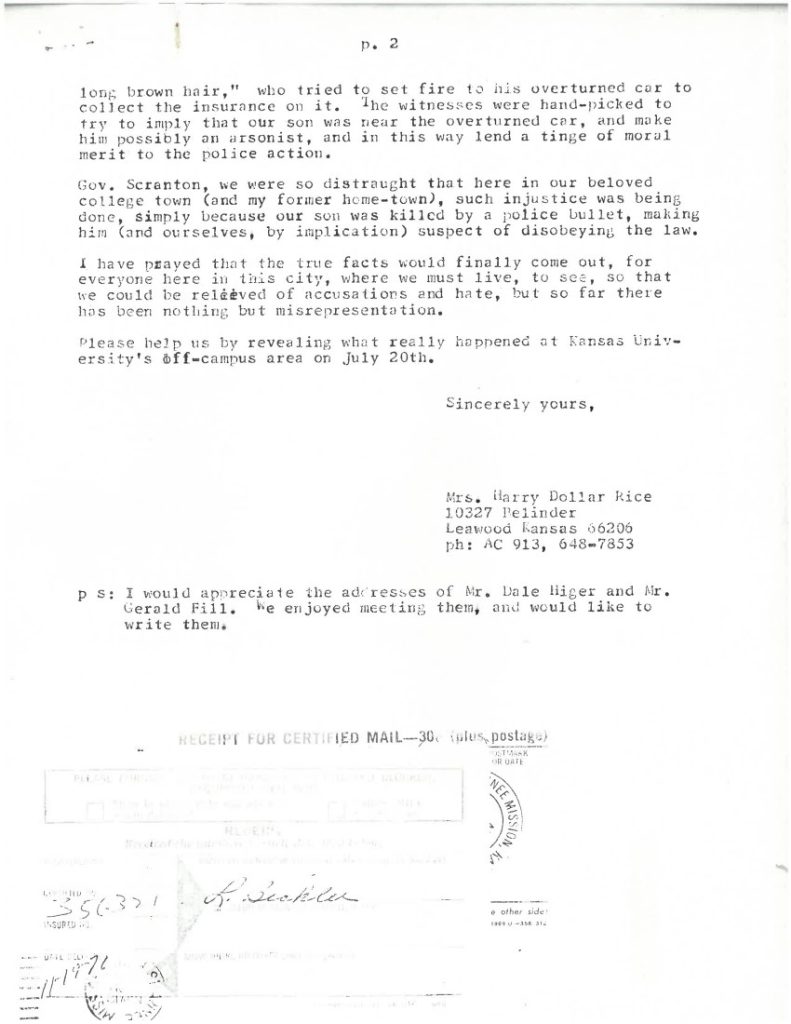

Nixon responded to the national situation with the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest. Mrs. Rice wrote to the head of the Commission, former Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton. She describes the inquest that seemed to implicate her son rather than the police and her hope that the Commission’s report would set the record straight.

While the Commission admonished law enforcement for responding to mostly peaceful protests with violence and advised the U.S. President that ending the war in Vietnam would lead to more peace domestically, it did not go into the details of the Nick Rice shooting. In a social and media environment that blamed their son and the protesters for the violence, the Rice family filed a suit against the city of Lawrence for damages in the wrongful death of their son. After years of litigation, including fighting the KBI for access to their full investigation, the family decided to drop the case.

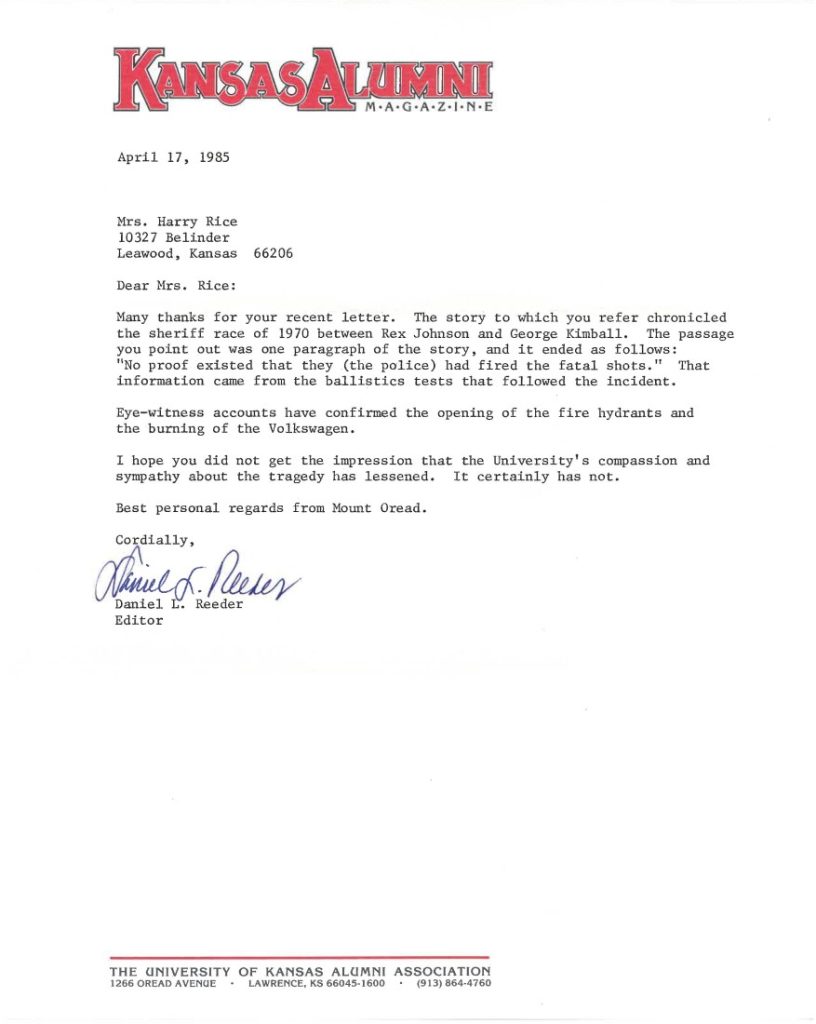

Esther Rice wrote of the experience in a manuscript called “Who Killed Our Son? An Account of the Circumstances and Subsequent Investigation of the Death of Harry Nicholas Rice” (Call Number: RH MS P617) that is also available at the Spencer Research Library. Over the years she continued to respond to news outlets that reinforced common narratives misrepresenting the case, such as the Kansas Alumni Magazine. While the files don’t include a copy of her letter, the editor’s response to her objection is included, along with the magazine in question.

In absence of hard evidence, many newspapers reported that the overturned car burned that night, and some suggested that Rice was shot by sniper fire. It is unclear what “eye-witness accounts” the Alumni editor is referring to, but the KBI files include nearly one hundred eyewitness accounts. These files are the basis for this summary of the events, and they make it clear that the Volkswagen was turned over, but never burned. The files also show the statement “no proof existed that (the police) had fired the fatal shots,” to be untrue. The proof existed; it just wasn’t released to the public.

According to The Lawrence Times, Nick’s brother Chris Rice paid thousands in legal and copying fees to gain access to the files from the KBI. More than fifty years after the shooting, Chris finally learned the truth. Rice donated the files to the Spencer Research Library, and they are now ready for viewing in the Reading Room.

The Personal Papers of Harry Nicholas Rice include those photocopies of the KBI investigation, as well as Mrs. Rice’s correspondence with federal officials and personal papers dealing with the case against the city of Lawrence. Also included are magazines, newspaper clippings, and correspondence kept by the family. Spencer Research Library is honored to preserve these papers and to make the facts of the police shooting of Nick Rice available to the public for the first time.

Erika Earles

Manuscripts Processor