Manuscript of the Month: A Manuscript, Wrapped in a Mystery, Inside an Enigma

April 1st, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

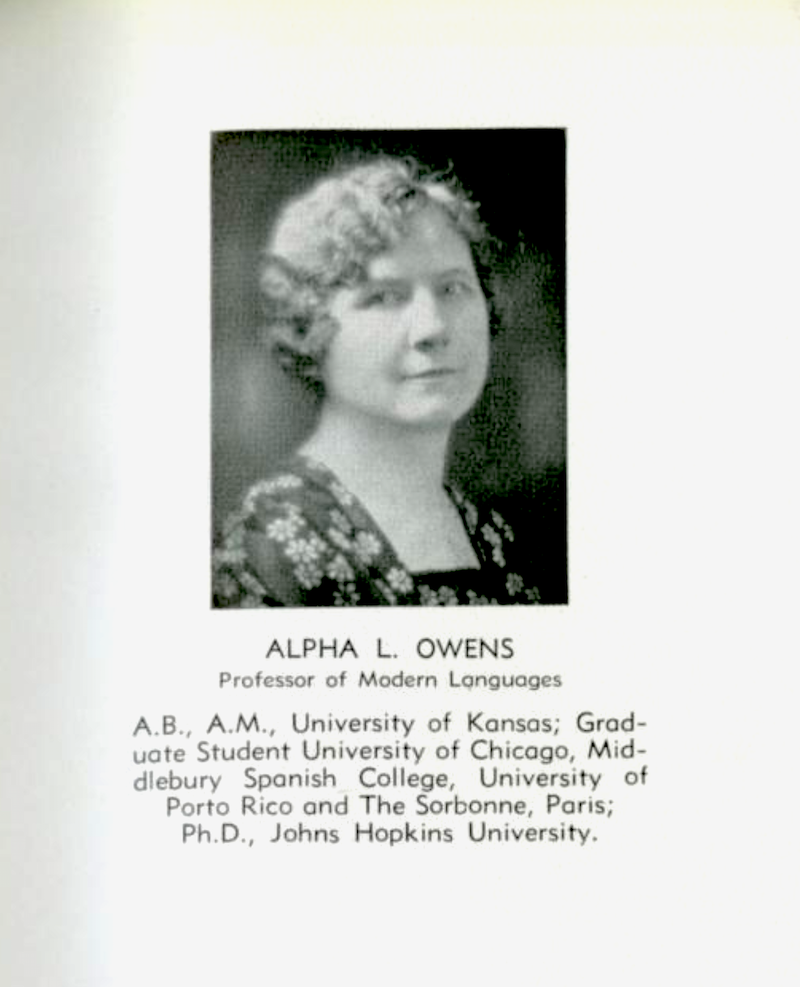

A small quarto manuscript, MS C189, previously belonged to Alpha Loretta Owens (1877–1965), a graduate of the University of Kansas. Born in Rockwell City, IA, her family moved to Lawrence, KS, after she finished high school. She completed her first degree over a century ago, in 1901, at the University of Kansas and went on to receive an MA in 1903, also from KU. She then attended the University of Chicago, where she later worked at the John Crerar Library until 1918. Following a brief post teaching French at the University of Kansas ROTC, between 1919 and 1926 she taught French at Baker University in Baldwin City, KS, where she became Head of the French Department. In 1929, she completed her PhD at Johns Hopkins University and became Professor of Modern Languages in West Virginia at Morris Harvey College (now the University of Charleston). She taught French, Spanish and German there until her retirement in 1947. Subsequently, she returned to Lawrence, where she resided until her death. Owens also was the previous owner of another manuscript currently in the holdings of the Kenneth Spencer Research Library, MS J1:2, a fragmentary Torah scroll. Paul Mirecki from KU Religious Studies has been working on the history of this manuscript, the details of which were outlined in an article last year in the KU Alumni Magazine.

MS C189 is one of three manuscripts that were listed under “The Library of Miss Alpha Loretta Owens, Barboursville, West Virginia” in the famous Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada prepared by Seymour de Ricci with the assistance of W. J. Wilson and published between 1935 and 1940. According to the Census, all three manuscripts were examined by Wilson in 1935, when Owens was working at Morris Harvey College and living in Barboursville, WV, where the University of Charleston was originally founded and based. This is all we know about the history of MS C189; that the manuscript was purchased by Owens sometime before 1935. It is not known when, where and from whom she acquired the manuscript. Nor do we know any other previous owners or the origin of the manuscript.

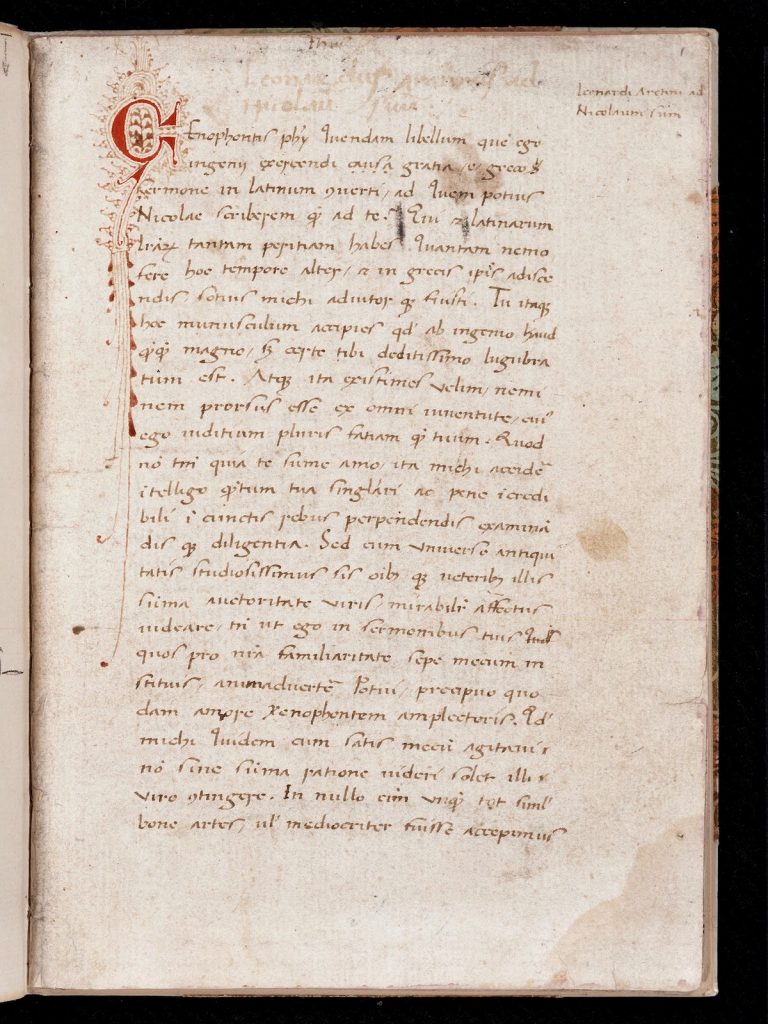

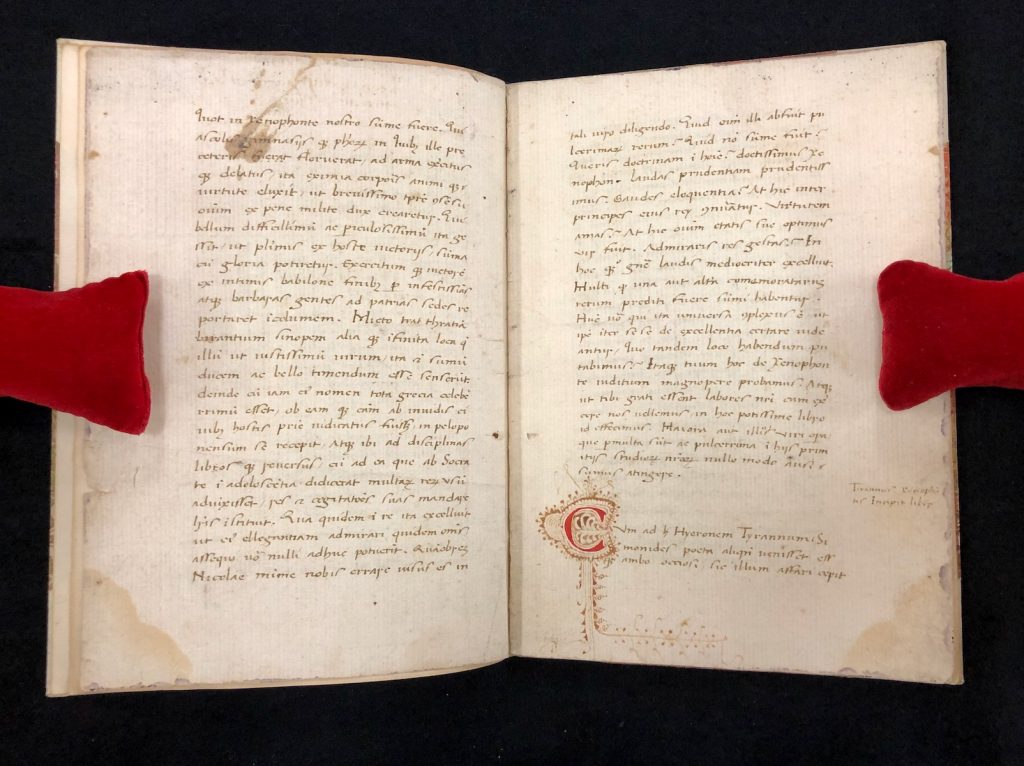

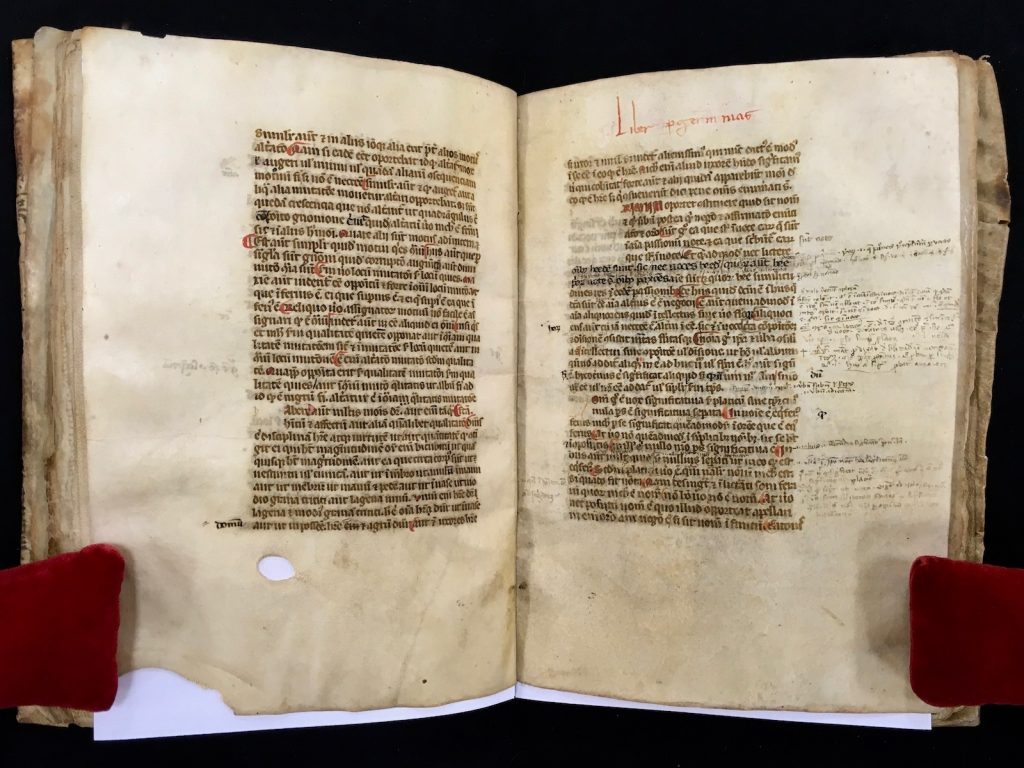

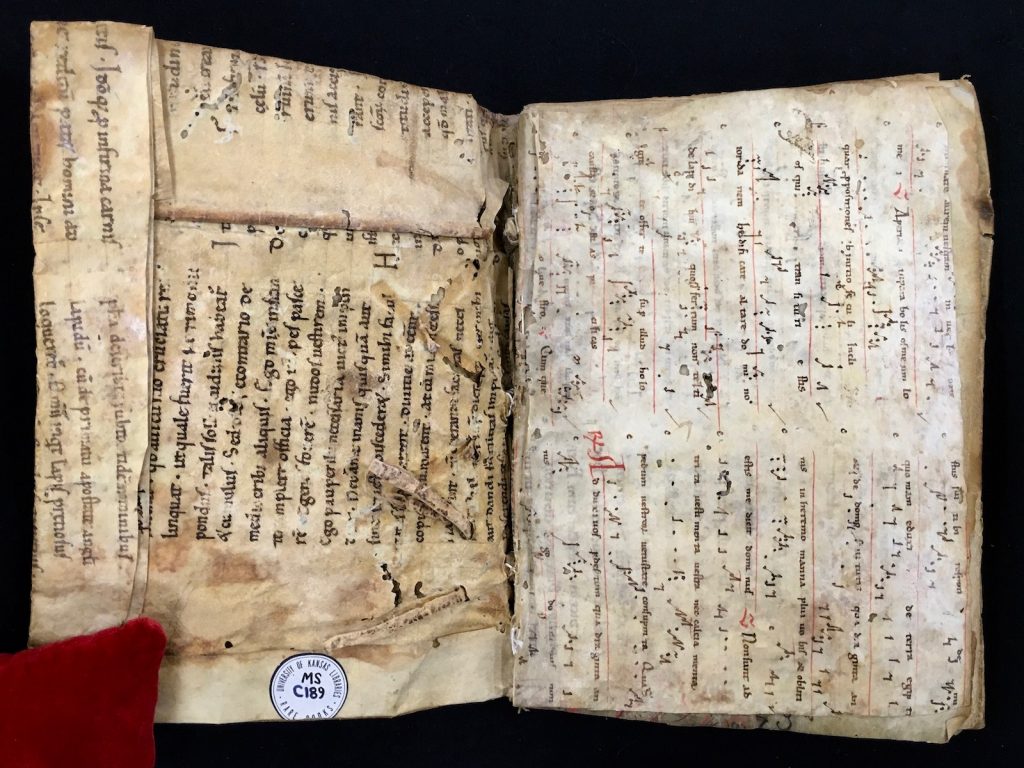

MS C189 is a remarkable object beyond the texts it contain. The textblock of the manuscript is homogeneous; that is, MS C189 is composed of a single codicological unit which was produced in one process and most openings look pretty much like the example provided above. It does not look like there are any missing leaves or like there were more gatherings either in the beginning or at the end. Parts of other manuscripts, however, were used as practical means to preserve this small book of 34 leaves as well as to support it. The binding of MS C189, which is presumably original, comes from another manuscript, as do the flyleaves in the front and the back from two others. Thus, we have one medieval manuscript that is placed inside fragments of two different medieval manuscripts and then wrapped with another one.

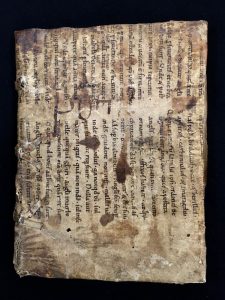

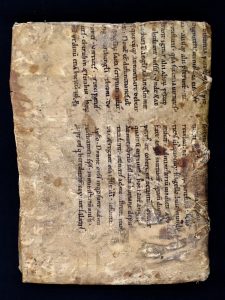

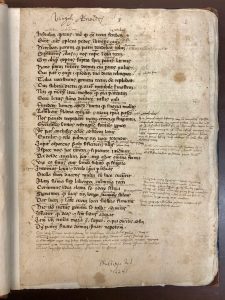

Left: Front cover of MS C189. Right: Back cover MS C189.

MS C189 has a limp binding, in which a bifolium (that is, two conjoint leaves) from another manuscript is used as a cover in the form of a case. The repurposed parchment cover is attached to the bookblock by means of split lacing double sewing supports made out of leather. The sewing-support slips are laced out of each side of the cover through three single exit slits and then each double support returns through two separate slits, one at approximately 45 degrees above and the other at 45 degrees below the exit slits, creating a V shape. What used to be the upper margin of the bifolium (now the fore-edge turn-in of the front cover) is trimmed, with all edges of the cover left large enough to allow for turn-ins. The cover has lapped mitres; the fore-edge turn-ins lie on top of the head and tail turn-ins at the corners. There is no lining or any kind of other reinforcement and the sewing-support slips, which are mostly intact, are fully visible.

Considered original, in the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, the binding of the MS C189 is described as made from two leaves of a twelfth century theological manuscript. There is no other information provided regarding the fragment. Furthermore, since then, neither MS C189 as an artefact nor this fragment now fashioning the cover of the manuscript seem to have attracted any attention from scholars.

The parchment leaf that now forms the outer cover (the recto side of the first of the two folios) of MS C189 is almost fully visible without any intervention. Except for the trimmed upper margin, it looks like the entire leaf is preserved. Moreover, there seems to be no loss of text due to trimming. Most of the text also is still readable on the cover and the turn-ins. I was able to identify the existing text as a part of Isidore of Seville’s Sententiae (Sentences). Composed in the early seventh century, the Sententiae employs the ancient and medieval literary form of collecting brief passages on a given topic. The work as a whole consists of three books (in thirty-one, forty-four and sixty-six chapters respectively) in which Isidore creates a compendium of essentials of theology in an organized manner.

Isidore of Seville’s Sententiae was fairly popular and there are many copies of manuscripts that survive from the Middle Ages. Indeed, we have another manuscript, MS C54, that contains the Sententiae. Therefore, when I identified the text, I was expecting the conjoint leaf whose verso is partly visible on the interiors of the cover to contain a different part of the same text. The text on the outer cover is from Book 10.11 of the Sententiae, a chapter entitled “De angelis” (On the Angels). The text on the inner cover, however, is not from the Sententiae but instead is part of a sermon attributed to John Chrysostom, who was the Archbishop of Constantinople at the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth centuries. The sermon is simply known by the title “De misericordia” (On Mercy) or by its opening words, “Tria sunt quae in misericordiae opera,” which are not visible in MS C189.

Further research revealed that this chapter of Isidore of Seville’s Sententiae was sometimes used as part of medieval homiliaries. A homiliary, or a book of homilies, is a collection of short texts consisting of lectures or discourses on a moral theme, which are also known as sermons. More research (and perseverance) revealed that there is at least one other manuscript in which both of these texts are found. In Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 3783(2), known as the Moissac Homiliary, not only do they both exist in the same manuscript but they are also in the same order that we have them.

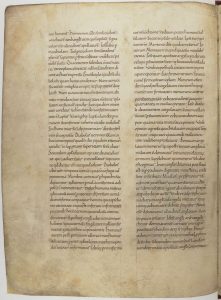

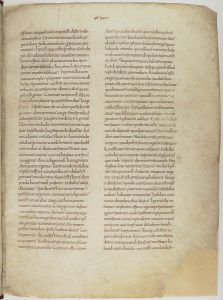

Left: The portion of “De angelis” in Latin 3783(2), folio 279v that corresponds to MS C189. Right: The portion of “De misericordia” in Latin 3783(2), folio 286r that corresponds to MS C189. Source: Gallica, Latin 3783(2), Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits.

According to the description of the Moissac Homiliary, Isidore of Seville’s “De angelis” opens a gathering of eight folios and the pseudo-John Chrysostom’s “De misericordia” closes it, with a series of shorter texts with similar topics in between the two (folios 279 to 286). The Moissac Homiliary is dated to the mid-eleventh century and is thought to have been compiled in Moissac Abbey in south-western France. What is now the binding of MS C189 probably looked like this manuscript in its original form. Both the cover of MS C189 and the Moissac Homiliary are written in late Caroline minuscule and both are laid out in two columns on folios of approximately the same size. The cover of MS C189 has 38 lines to a page whereas the Moissac Homiliary has 37 but seems to be a little bit more compact and has large initials in the beginning of each section. (We do not know whether the cover of MS C189 originally had any illuminated initials in the same places.) If the biofolium we have as the cover of MS C189 was indeed part of a larger book with a similar arrangement with six bifolia in between the two leaves we have, the two texts would fall more or less to the same places. It seems more than likely, therefore, that MS C189 and the Moissac Homiliary are related, possibly one copied from the other.

Additional research on MS C189, with all of its features and fragments, would certainly yield further answers as to how the manuscript came to be and perhaps even how it ended up in Alpha Loretta Owens’s collection in the early twentieth century.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Book Nook in May 1966, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher