Manuscript of the Month: What Is in a Medieval Chronicle?

June 30th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

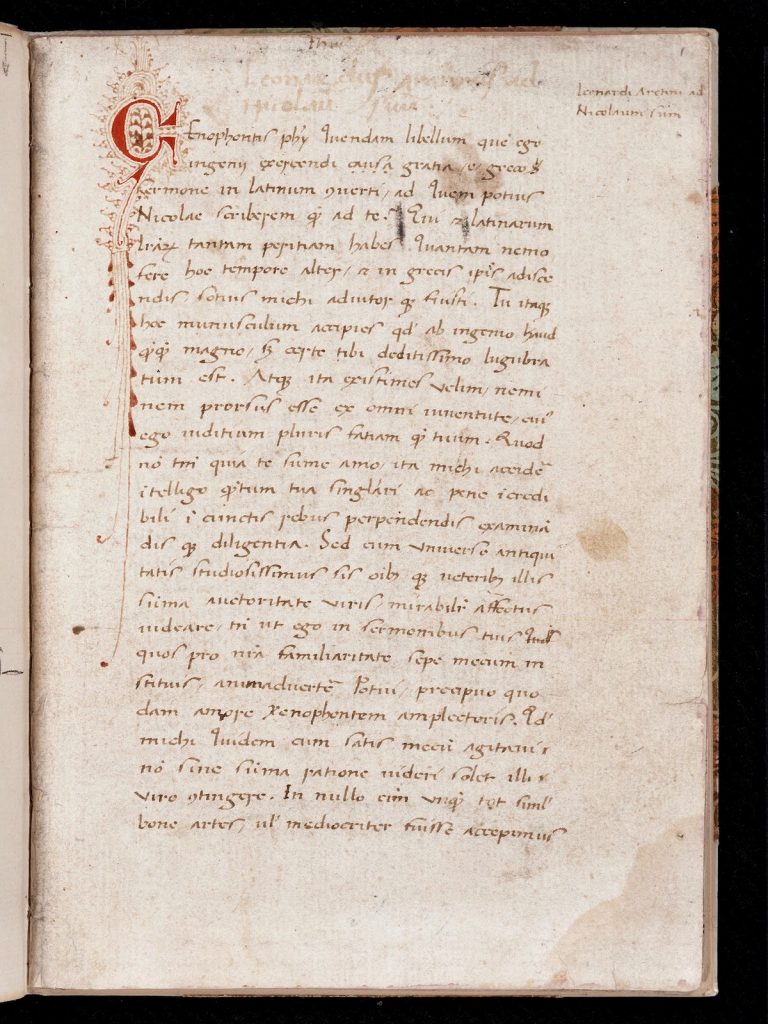

The description of Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS B90 was titled “Contemporary Manuscript of the World Chronicle of Martin of Troppau” in William Salloch’s Catalogue 258 dated to 1968. Marianne and William Salloch were the founders of the successful bookselling business based in New York, William Salloch, Old, Rare and Scholarly Books. William (1906–1990) was a medievalist by training and the 422 catalogs he and Marianne issued between 1939 until 1989 went beyond being simple sales listings for rare books and manuscripts, becoming reference books in their own right. Over the years, the University of Kansas acquired several manuscripts from the Sallochs, including this one and another, MS D13, that was the topic of my blogpost last month.

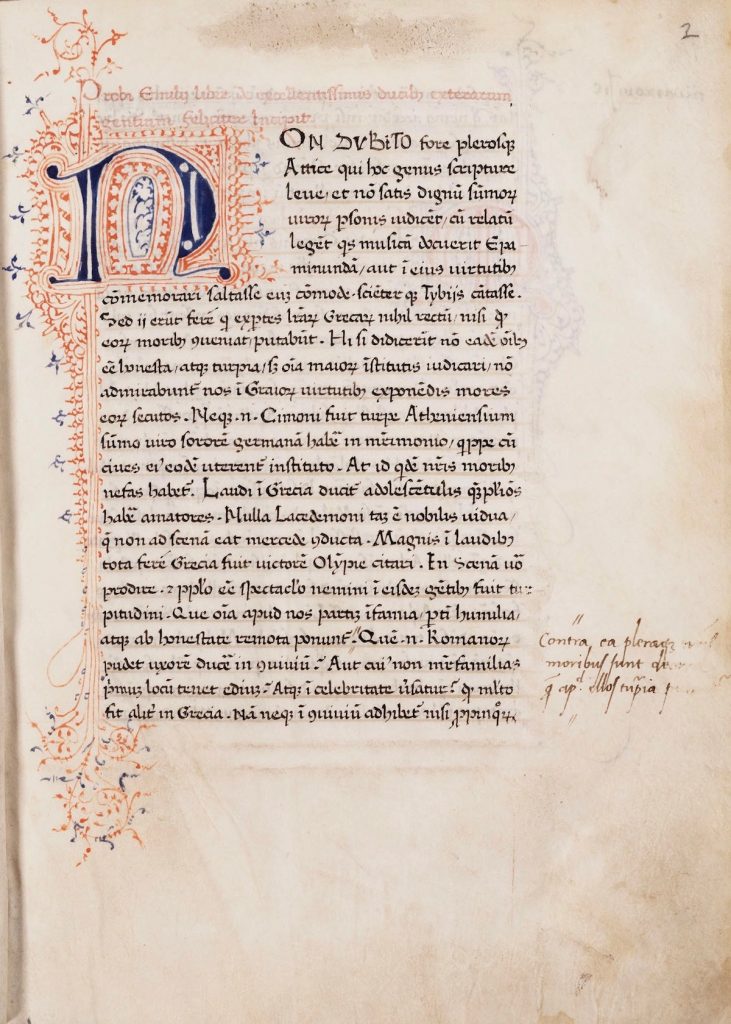

The author in question, Martin of Troppau, is better known in English today as Martin of Opava or Martin of Poland (from Martinus Oppaviensis or Martinus Polonus in Latin). Based on contemporary references, it is thought that Martin was from Opava (Troppau in German), today a city in the Czech Republic, and was born sometime before 1230. A Dominican friar, he became active in Rome and served the Papacy first under Pope Alexander IV (1199 or around 1185–1261) and then under several of his successors until his own death in 1278, shortly after being appointed Archbishop of Gniezno in central-western Poland. As the author of the Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum (The Chronicle of Popes and Emperors), Martin of Opava is considered by many scholars to be the most influential European chronicler of the later Middle Ages. The Chronicle is estimated to have survived in around 500 manuscripts in the original Latin as well as in several translations, including Greek, Armenian and Persian in addition to western European vernacular languages. It was also used as a source or continued with current events by later chroniclers.

Soon after the acquisition by the Spencer Library of item no. 10 in the Sallochs’ Catalogue 258, the manuscript was given the shelfmark MS B90 and was cataloged under the name “Martinus Polonus” in the in-house manuscript catalog of the Library called Catalog IV. This information was later transferred to the description in the online catalog of the University of Kansas Libraries and later also to that of the Digital Scriptorium website, which serves as an online union catalog and image repository for US institutions, of which Spencer Library is a member.

It was noted in the Salloch’s catalog description that “the history of the text and its tradition is quite complicated since Martin of Troppau revised his own history several times; each manuscript offers an original and different text.” This warning in disguise was followed by a list of scholarly works including Ludwig Weiland’s 1872 edition of the text in the renowned Monumenta Germaniae Historica series, which remains the only modern edition of Martin of Opava’s Chronicle. During the half century since the manuscript was purchased by the Spencer Library in 1969, no one has embarked on verifying the information provided by the bookseller, that is, whether or not the work in MS B90 is in fact Martin of Opava’s Chronicle. Despite her careful examination of the contents of the manuscript, Ann Hyde, the former Manuscripts Librarian at the Spencer Library, noted in the entry she made for Catalog IV: “I did not examine these works [the edition of the text and the other reference works mentioned in the description by Salloch] and do not know where our version stands in the text-pedigree, or if it is known at all.”

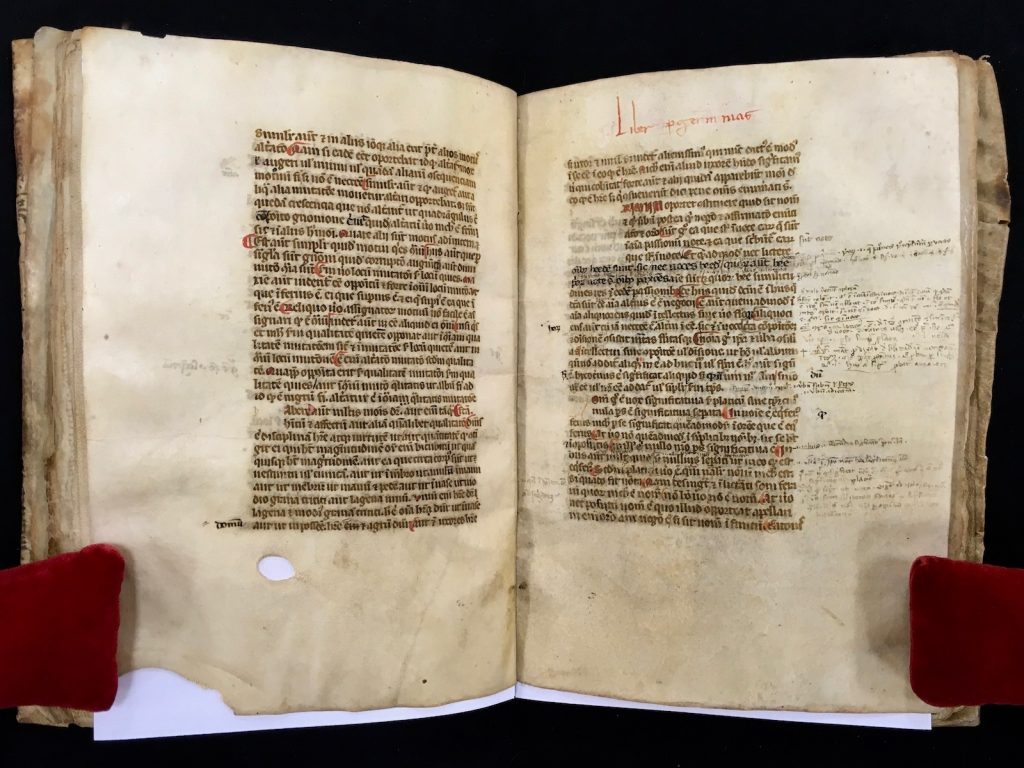

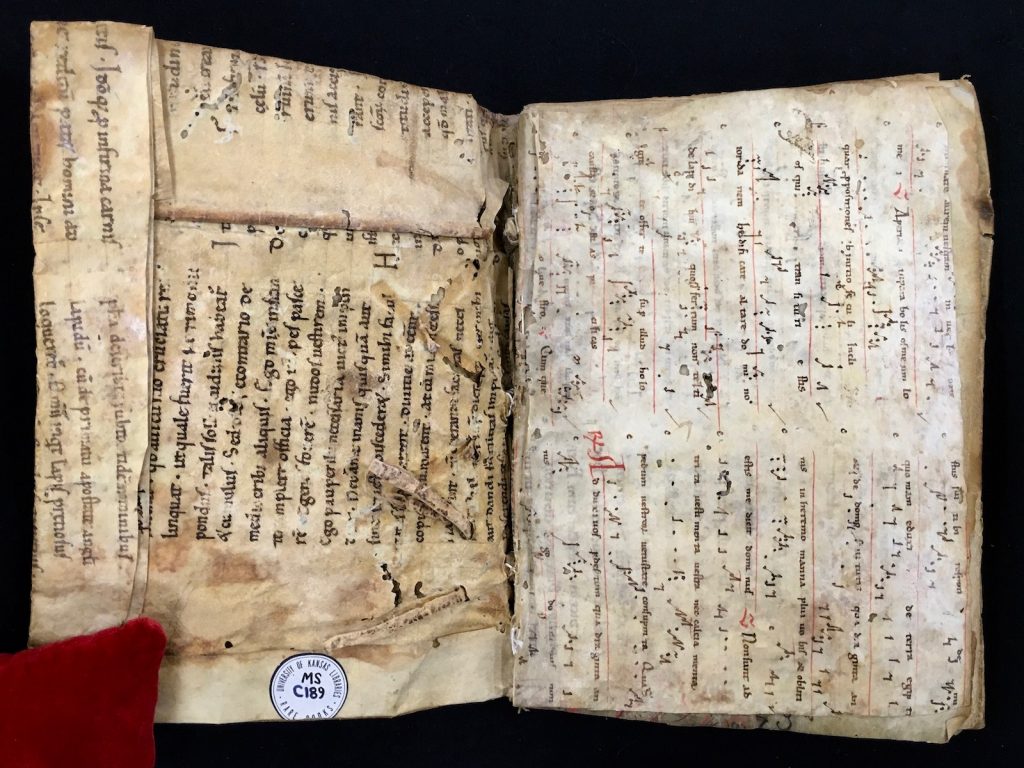

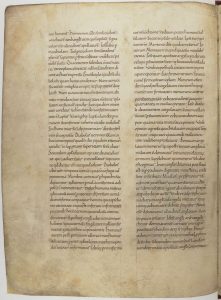

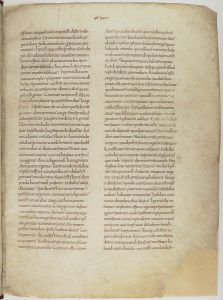

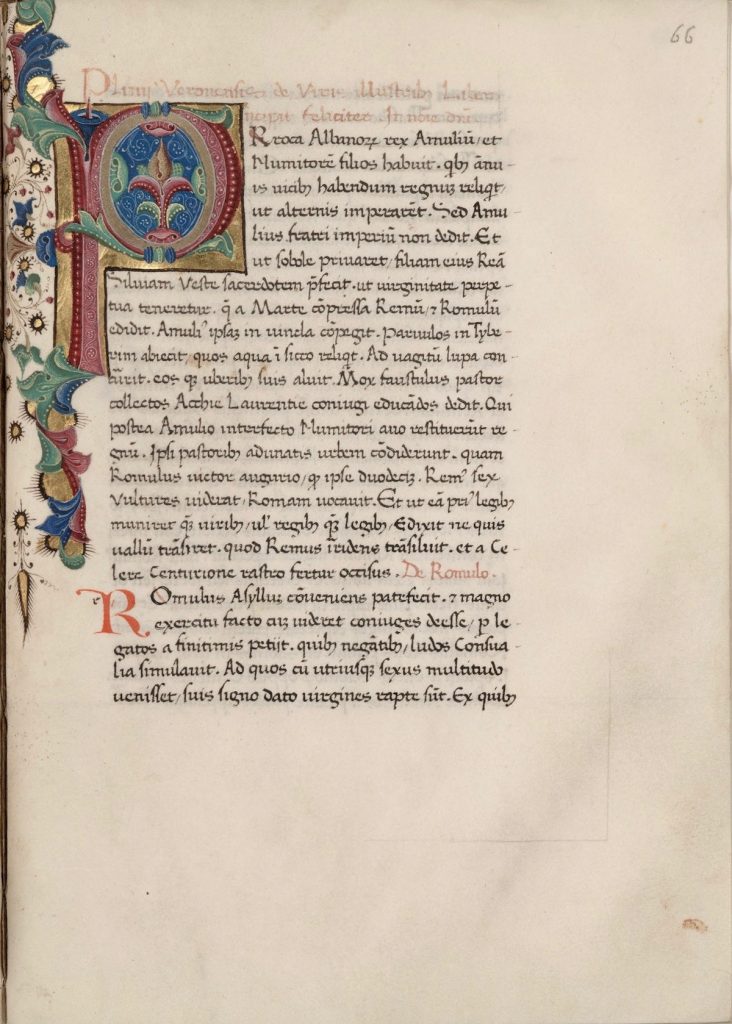

The text preserved in MS B90 is one of the so-called “pope-and-emperor chronicles,” a famous model for chronicles in the Latin Middle Ages, in which short biographies of popes and emperors of Rome were narrated in chronological succession from Antiquity to the contemporary present day. Martin of Opava was certainly not the first author to compile such a chronicle and he utilized several previous histories and chronicles as his sources. He envisaged, however, a novel layout for his Chronicle, in which each page had fifty lines and each line corresponded to a year. He further arranged his chronicle so that the history of the popes faced the history of the emperors in any given opening of the book. Thus, each opening would depict a fifty-year period, with the papal and imperial histories also chronologically aligned. In the final version of his Chronicle, this tabular history of the popes and emperors was prefaced by a geographical and historical introduction, especially focusing on Rome.

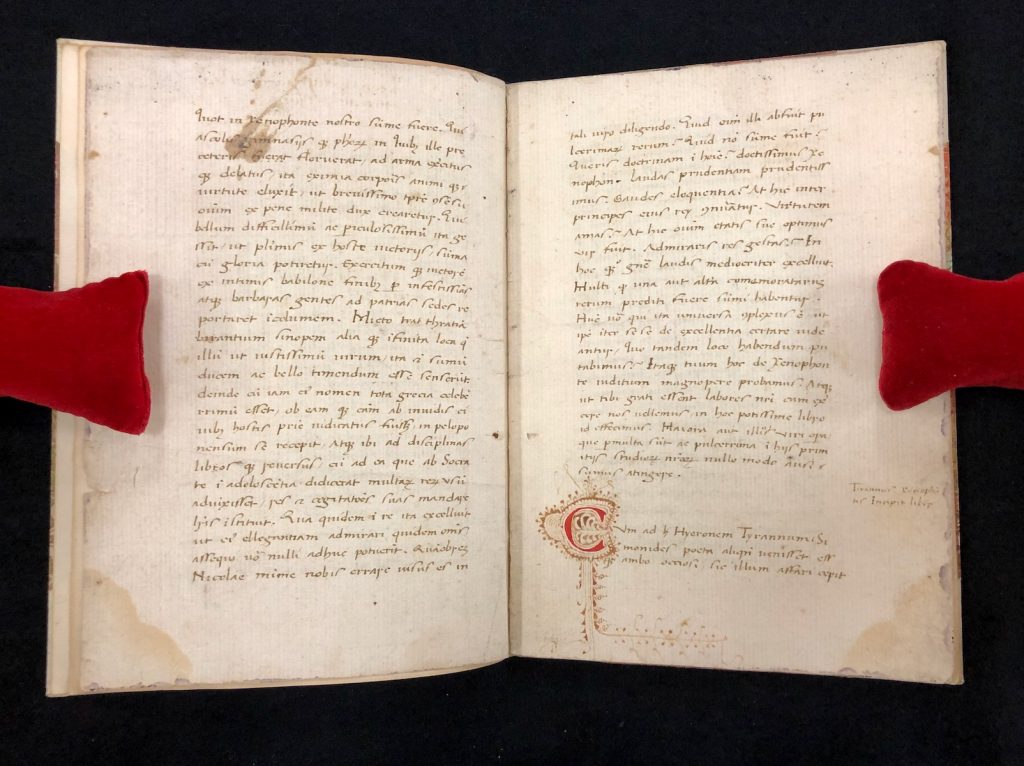

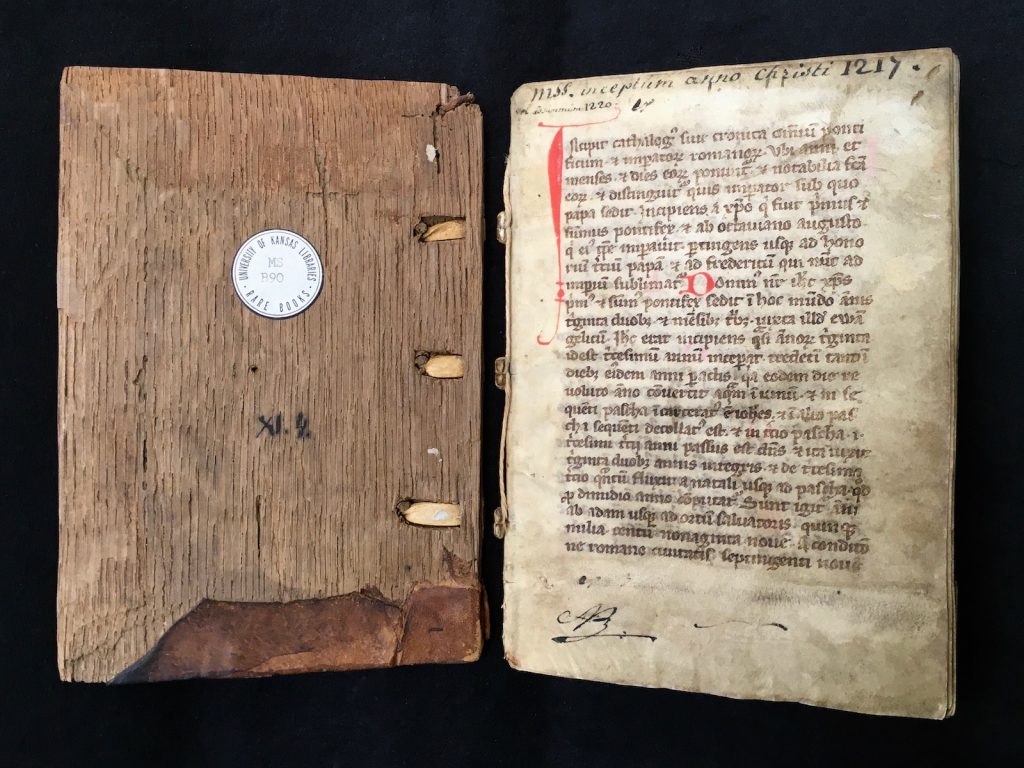

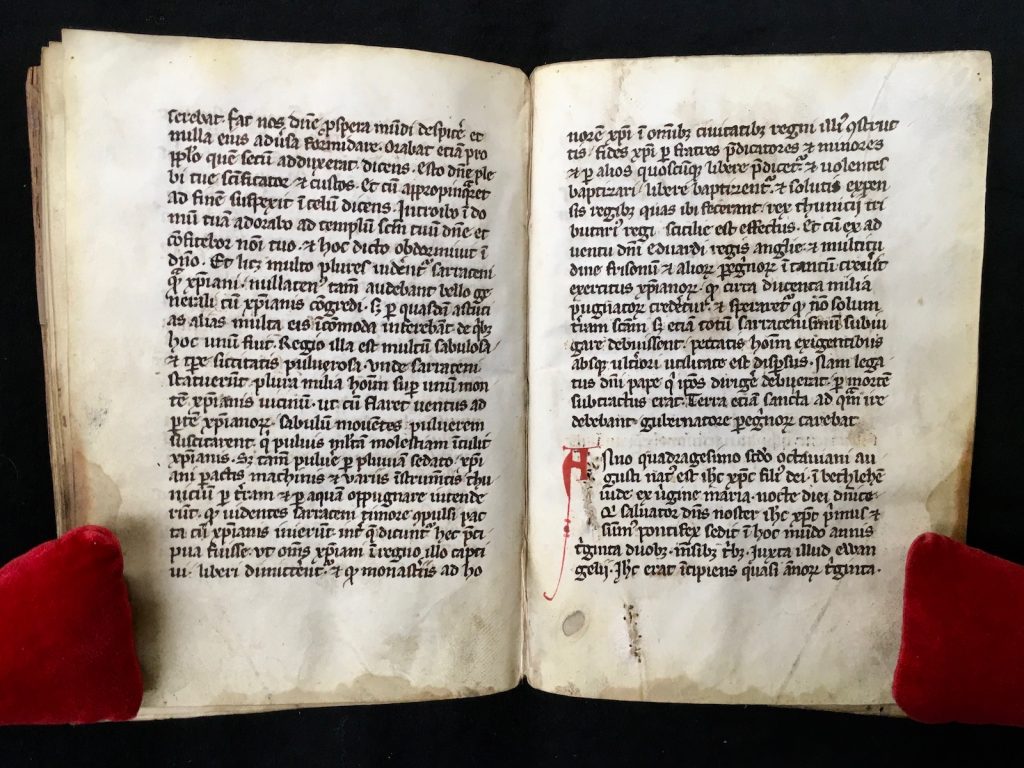

Not all later scribes adhered to Martin of Opava’s original layout of tabular, parallel histories when they copied his Chronicle. It can be immediately seen that a parallel layout was not the case in MS B90 either. Written by a single hand, the text in MS B90 runs like a narrative with no schematic arrangement and the papal accounts precede the imperial ones. The manuscript opens with the following rubric (fol. 1r):

Incipit cathalog(us) sive cronica om(n)iu(m) ponti | ficum (et) imp(er)ato(rum) Romano(rum) ubi anni et | menses (et) dies eo(rum) ponunt(ur) (et) notabilia f(a)c(t)a | eo(rum) (et) distinguit(ur) quis imp(er)ator sub quo | papa sedit. Incipiens a (Christ)o q(ui) fuit p(ri)mus (et) | su(m)mus pontifex (et) ab Octaviano Augusto | q(ui) ei(us) t(em)p(or)e imp(er)avit p(er)tingens usque ad Hono | riu(m) t(er)ciu(m) papa(m) et ad Fredericu(m) qui nu(n)c ad imp(er)iu(m) sublimat(ur).

In this very brief preface, the reader is told that this is a chronicle of all popes and Roman emperors and that it will begin with Jesus Christ and the Emperor Augustus, who reigned during Jesus’s youth, and continue until Pope Honorius III and Emperor Frederick, who is now in power. Pope Honorius III was the head of the Catholic Church from 1216 until his death in 1227. During that time, Frederick II was the Holy Roman Emperor, between 1220 and 1250. The mention of Honorius III and Frederick II as the endpoint of the chronicle indicates that they were the author’s contemporaries, which in turn provides a time frame in which this preface was put down into writing: not before 1220 and not after 1227. This is when Martin of Opava was probably not even born.

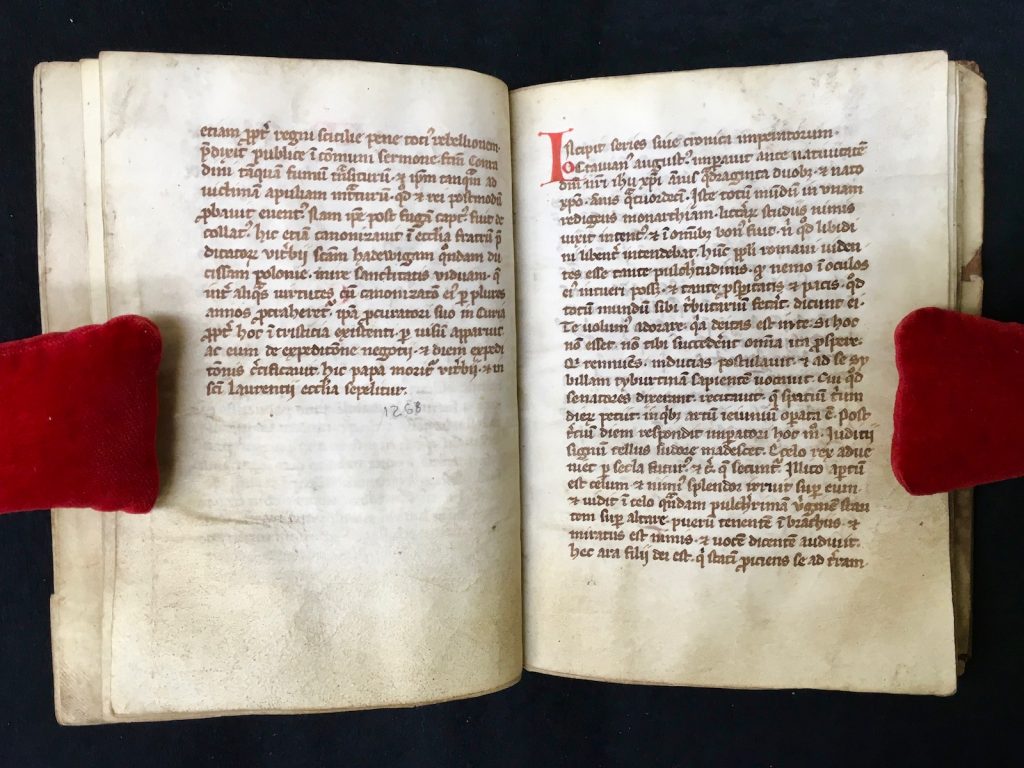

Indeed, this same preface is found in another pope-and-emperor chronicle, written by Gilbert of Rome, which was among the many sources Martin of Opava listed in his much longer preface to his Chronicle. Nothing is really known about Gilbert (also known as Gilbertus Romanus) except that he was perhaps a native of Italy and that he was active in Rome. The 1879 MGH edition of the text, which again remains the only modern edition of Gilbert of Rome’s Chronicle to date, identifies less than 20 surviving witnesses of his Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum Romanorum (The Chronicle of Popes and Emperors of Rome). What is more, the majority of the accounts of the popes in MS B90 follow Gilbert of Rome’s Chronicle almost to the letter. Some of the popes, however, such as Pope Sylvester II (999–1003) and Pope Gregory VII (1073–1085) receive a longer treatment than it is found in any of the other known witnesses of Gilbert’s Chronicle. Furthermore, the accounts of the popes do not conclude with Pope Honorius III as was promised in the preface but instead continue seamlessly until Pope Clement IV (1265–1268). These observations on the papal accounts indicate, on the one hand, that the prologue in MS B90 was copied from Gilbert’s Chronicle and the text is heavily based on it (up to the 1220s) but, on the other hand, that there are additions that take the accounts of the popes to the late 1260s.

Whereas the account of the popes concludes with Pope Clement IV, whose papacy ended on November 29, 1268, the account of the emperors ends with the year 1270 in MS B90. Although this seems like a discrepancy at first sight, it is not surprising. Following the death of Pope Clement IV came the longest papal election in the history of the Catholic Church and the successor of Pope Clement IV, Pope Gregory X, only began his office on September 1, 1271. This special set of circumstances enables us to date the text to sometime in 1270 or early 1271.

Most of the accounts of the emperors in MS B90 have additions to them that are not found in Gilbert’s Chronicle but neither do they match exactly that of Martin’s. The closest account that matches that of Martin’s is perhaps the account of Emperor Frederick II. This is in fact the last account in Gilbert of Rome’s Chronicle. After the narration of Frederick II’s reign, both MS B90 and Martin of Opava’s Chronicle begin narrating the events by year, starting with 1250. This final part of the text in MS B90 again does not match fully with that of Martin of Opava’s Chronicle. For example, the years 1259 and 1263, which get a special mention of events in Martin’s Chronicle, are completely left out in MS B90.

Following the end of the accounts of the emperors with the year 1270, MS B90 has an additional account on the life of Jesus Christ that spans fols 51r-52v. And, this is in fact how Martin’s account of the popes with Jesus Christ begins in his Chronicle. Although again not an exact match, the version in MS B90 is quite close to what is recorded in Martin’s Chronicle. The fact that this extended, longer version of the account of Jesus Christ is appended to the end of the text as a discrete section, especially when another version of the account is already narrated in the very beginning where it supposed to have been narrated, is quite intriguing. Relying on past sources, adding, subtracting, redacting and every aspect imaginable of réécriture were at the heart of medieval historiographical writing and in that regard MS B90 is no exception in displaying how texts came to be in the Middle Ages.

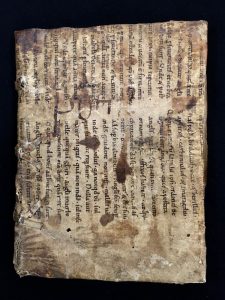

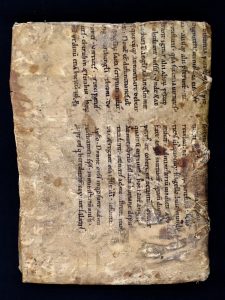

It is certain that the version of the Chronicle of Popes and Emperors we have in MS B90 was composed sometime around 1270. Whether the manuscript was also copied around the same time is another matter. A series of paleographical features in MS B90 such as the crossed Tironian et sign (⁊) and the letter a with open upper bow as well as certain codicological features such as the manner in which the wooden boards are attached to the bookblock may very well indicate that this manuscript was copied at the end of the thirteenth century, as suggested by Salloch. Therefore, it seems as though MS B90 is a clean copy of a very early draft of Martin of Opava’s notes, which consisted a copy of Gilbert of Rome’s Chronicle with expansions of some of the earlier accounts and additions until the year 1270. Since MS B90 has virtually no corrections or annotations, this cannot be Martin of Opava’s working copy, but rather a copy made from his notes before he began to expand and rewrite the majority of the accounts. Alternatively, this could be an expansion and continuation of Gilbert of Rome’s Chronicle, independent of Martin of Opava’s work, which may even have served as one of Martin’s as yet unidentified sources. Although it is clear that we can no longer call MS B90 a witness to Martin of Opava’s Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum, a closer investigation into the manuscript might reveal clues as to the earlier stages of his composition of his Chronicle.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from William Salloch in January 1969, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

Editions of both texts are available online:

- Gilbert of Rome. Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum Romanorum, ed. Oswald Holder-Egger. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores, SS 24, 117–140. Hannover: Hahn, 1879. [open access]

- Martin of Opava. Chronicon pontificum et imperatorum, ed. Ludwig Weiland. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores, SS 22, ed. Georg Heinrich Pertz, 377–475. Hannover: Hahn, 1872. [open access]

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about pre-1600 manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

![Image of a manuscript fragment (recto) possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century? The fragment had been repurposed as the cover of a codex.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/01.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1r-1024x683.jpg)

![Image of a manuscript fragment (verso) possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century? The fragment had been repurposed as the cover of a codex.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/02.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1v-1024x683.jpg)

![Image of a manuscript fragment possibly from Papias the Lombard’s Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum [Elementary Introduction to Learning]. France? Netherlands? 13th century?, digitally processed to enhance the legibility of water-damaged text.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/03.-KSRL_MS-9-2-16_folio1r_manipulated-1024x683.jpg)