‘Dead Coloring’ Revived Again: John Gould’s Hand-Colored Bird Lithographs

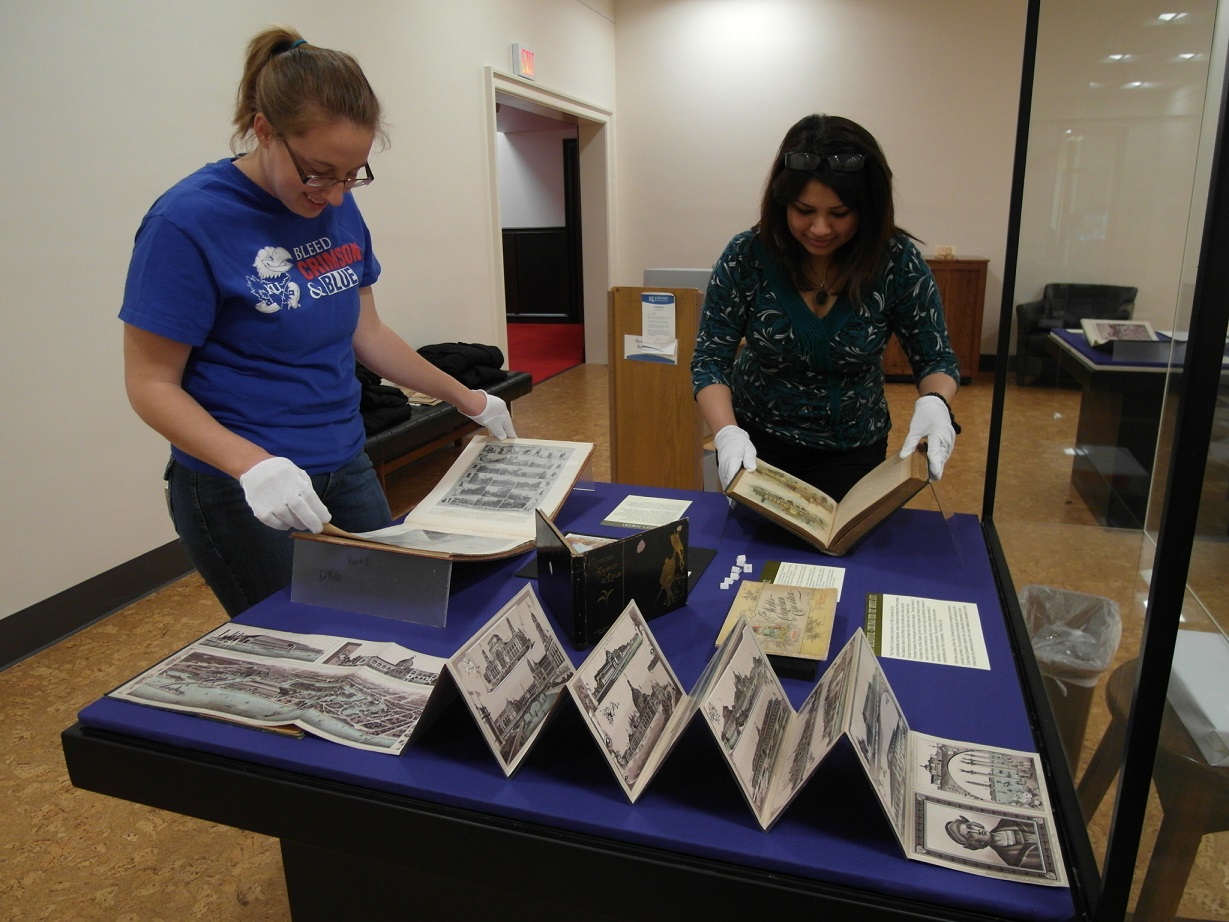

September 22nd, 2014Over the centuries a number of techniques for creating graphic images have outlived their original technology, successfully migrating to new imaging technologies. I was recently reminded of this while planning Kenneth Spencer Research Library’s exhibition, “Ornithological Illustration in the Age of Darwin: The Making of John Gould’s Bird Books” (open September 11-November 15, 2014 on weekdays 9-5 and Saturdays 9-1, except October 11).

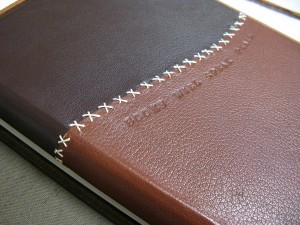

John Gould, an English ornithologist, published illustrated books about birds from 1830 until his death in 1881. The Library has recently digitized its holdings of Gould’s 47 large-format volumes, as well as nearly 2000 preliminary drawings, watercolor paintings, tracings, lithographic stones, and proofs.

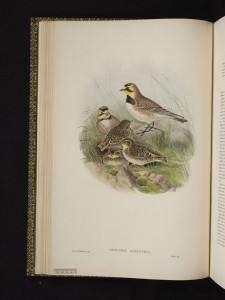

When searching the new digital John Gould Ornithological Collection (accessible at the University of Kansas Libraries website at http://lib.ku.edu/gould), I happened to compare the published hand-colored print of the Horned Lark or Otocoris alpestris with the black printing image on lithographic stone. “What a great example of dead coloring!” I exclaimed.

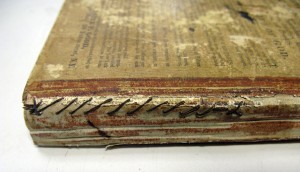

Otocoris alpestris / Horned lark. Lithographic crayon on stone by

John Gould and Henry Constantine Richter.

Reference: ksrl_sc_gould_2387.tif.

Call number: Gould Drawing 2387. Click image to enlarge.

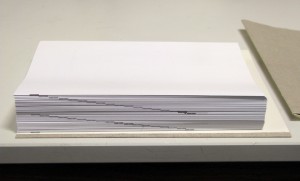

Otocoris alpestris / Horned lark. Lithograph and watercolor by

John Gould and Henry Constantine Richter.

Reference: ksrl_sc_gould_gb_1_3 (n77).

Birds of Great Britain, 1st edition, volume 3, plate 18.

Call number: Ellis Aves H131. Click image to enlarge.

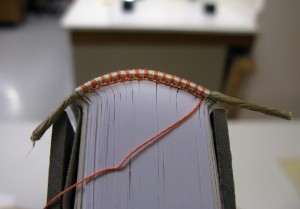

So what is dead coloring? It involves underpainting shapes in a neutral hue, then finishing the oil painting with transparent colored glazes, and was often used by late-18th-century English painters. Early painters in watercolor, a medium gaining popularity in England during the late 18th century, employed a similar approach.

However, dead coloring also had a place in European printmaking. Mezzotint and aquatint, new methods of intaglio printmaking capable of the tonal gradations necessary for dead coloring, were invented in the mid-17th century and increased in use thereafter. John James Audubon’s hand-colored aquatints of American birds published in the early 19th century were outstanding examples.

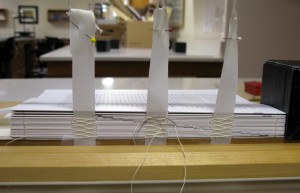

During the early 19th century yet another new printing technology, lithography, spread from Germany, where it had been invented in 1798, across Europe to England. Working with a waxy crayon on a block of lithographic limestone with a fine-textured surface was similar to drawing on rough-textured paper. The lithographic crayon caught on the tips of the grained stone surface, creating a random pattern of irregular dots. Viewed with the naked eye, the tiny dots merge into shades of gray.

Lithographic drawing was much easier to learn than mezzotint and aquatint and was the obvious choice for illustrating John Gould’s ornithological books. Elizabeth Gould (his wife), an amateur artist, rapidly mastered crayon lithography under the tutelage of Edward Lear, a younger but more experienced artist employed by Gould. She illustrated Gould’s books until her death in 1841, after which he employed a succession of professional artists.

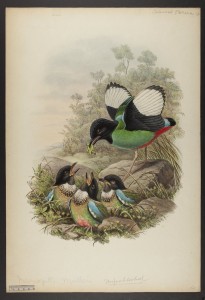

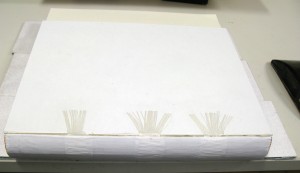

Melanopitta sordida. Watercolor and lithographic crayon drawing by

William Hart. Reference: ksrl_sc_gould_1264.tif.

Call number: Gould Drawing 1264. Click image to enlarge.

Melanopitta sordida. Colored lithographic proof by

William Hart. Reference: ksrl_sc_gould_1265.tif.

Call number: Gould Drawing 1265. Click image to enlarge.

Artist William Hart executed his drawing of Melanopitta sordida in lithographic crayon and watercolor, thus rehearsing his final drawing on lithographic stone for printing and hand coloring. Colored by hand using watercolors, Gould’s lithographic prints are successful examples of dead coloring. By the time of Gould’s death in 1881, color printing was taking over the reproduction of graphic images, bringing the hand-colored lithographic revival of dead coloring to a close.

Karen S. Cook

Special Collections Librarian