A Story from Quantrill’s Raid (And Possibly a Misidentified Photograph)

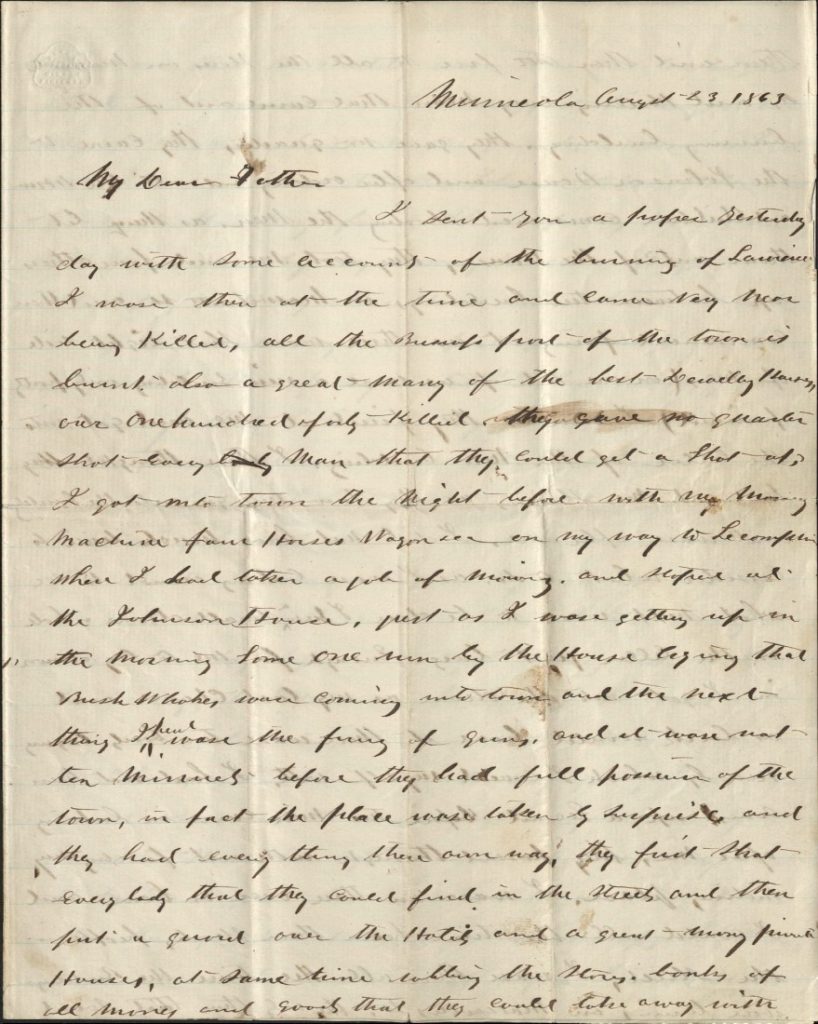

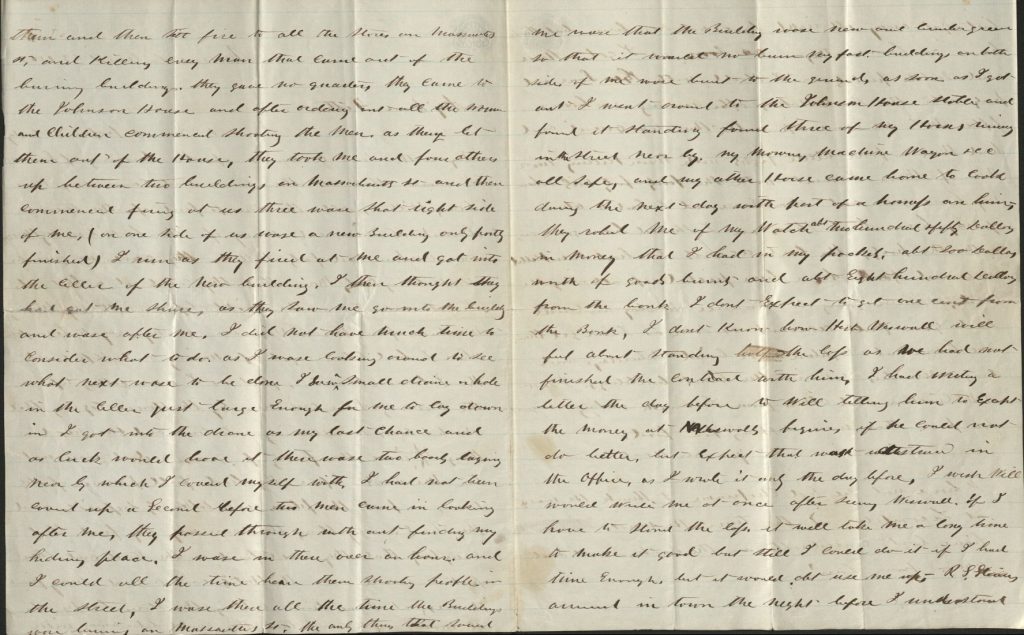

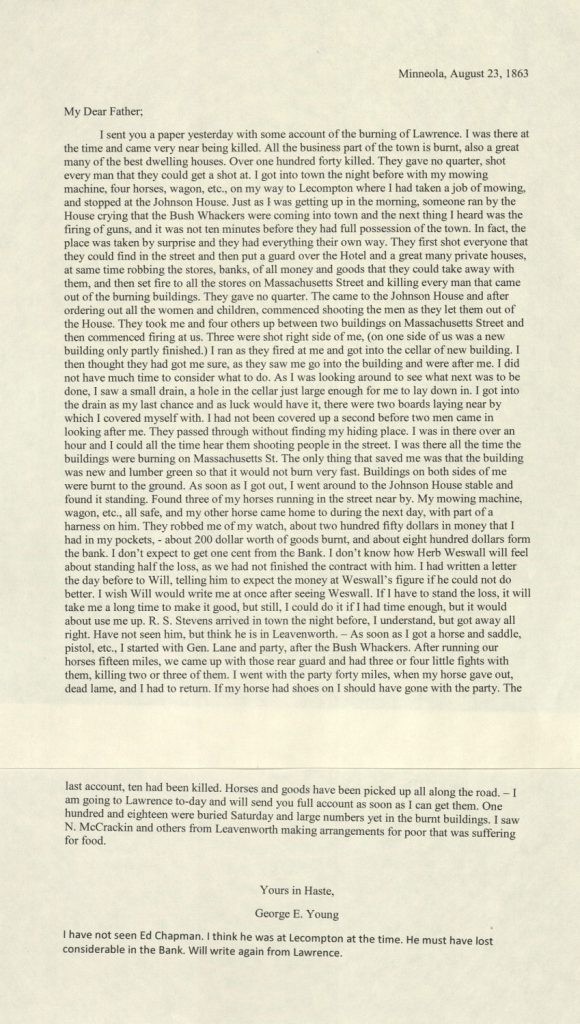

August 28th, 2024Last week was the 161st anniversary of the 1863 raid of Lawrence, Kansas, home to many free-state and abolitionist leaders. In the early hours of Friday, August 21, 1863, Confederate guerilla chief William Clarke Quantrill and 400 of his men rode into town, taking it by surprise. They ransacked homes, looted stores, set fire to homes and businesses, and killed close to 190 men and boys. The focus of this post is just one of the many personal stories from that awful day.

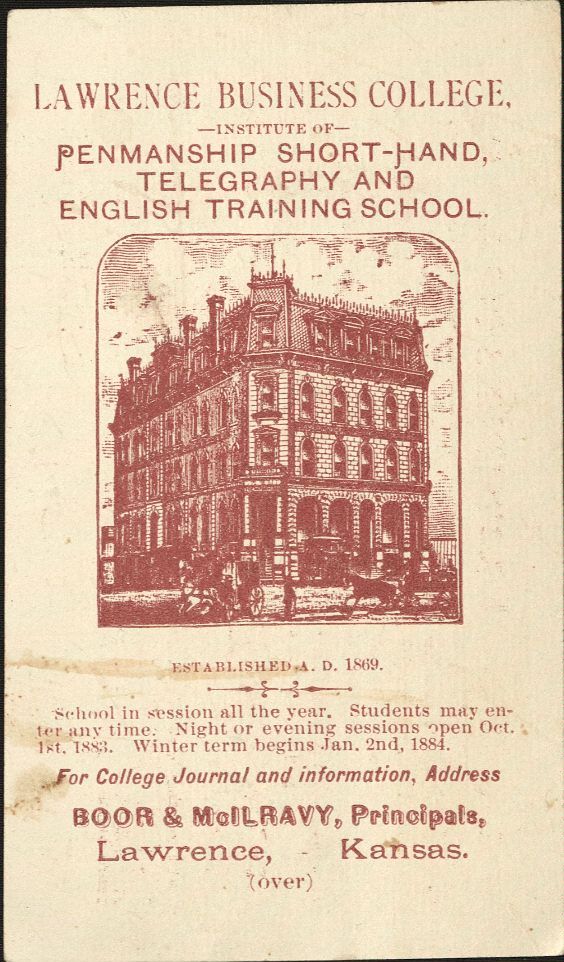

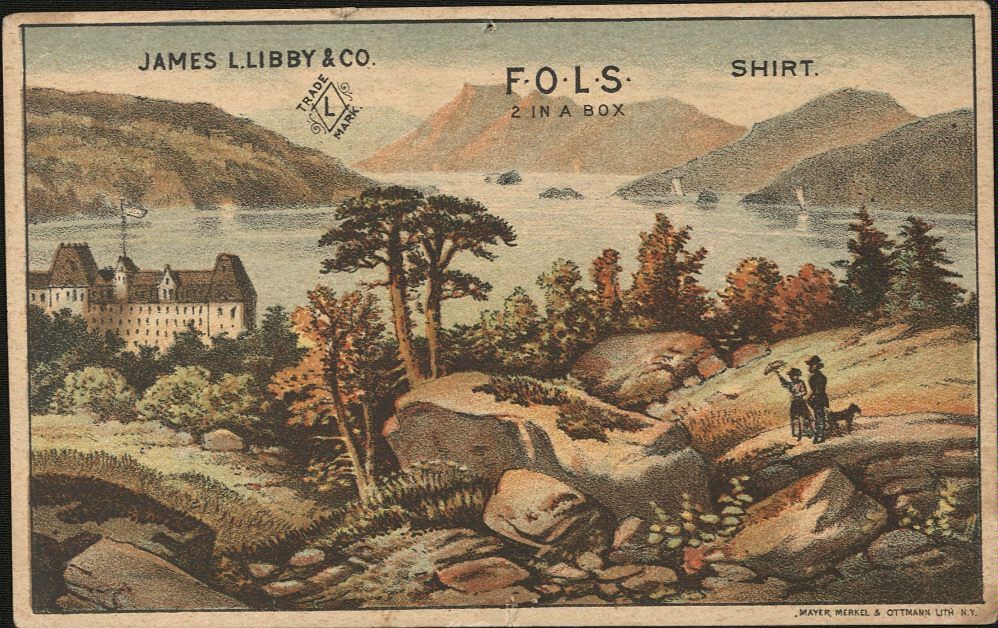

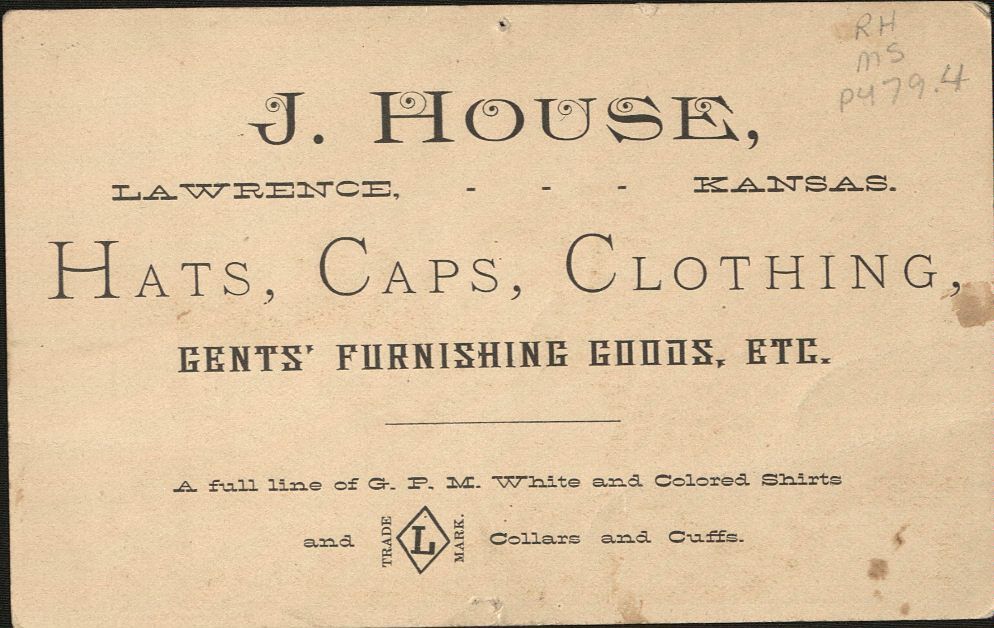

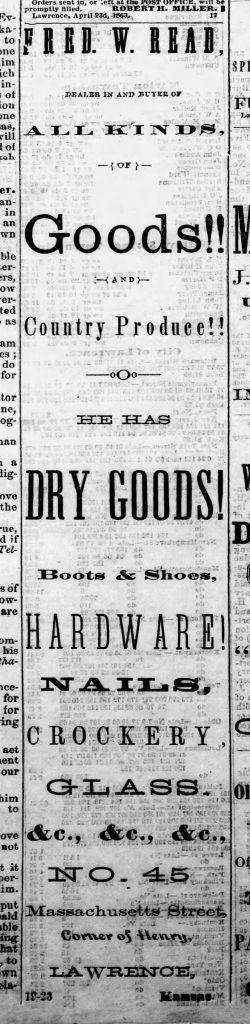

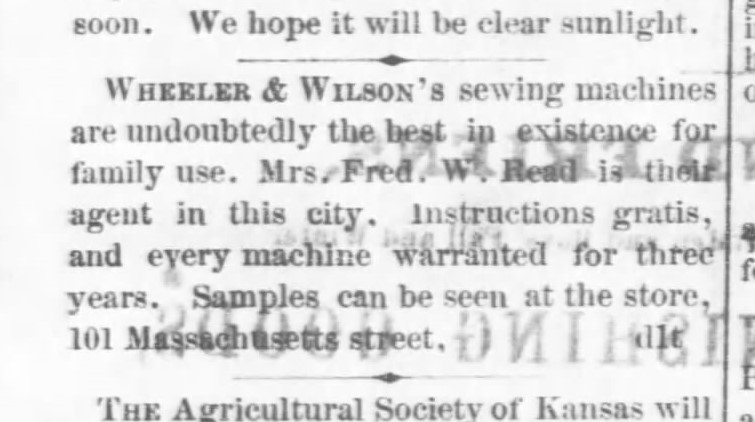

Frederick and Amelia Read were living and working in Lawrence at the time of the Raid. Frederick (1831-1901) immigrated to Lawrence from New York in 1857. It’s possible that he came as a member of one of the last parties of settlers sponsored by the New England Emigrant Aid Society, whose mission was to ensure that Kansas entered the Union as a free state (i.e. one that did not allow slavery). Frederick Read owned and operated a dry goods business for several years. After the Civil War, his wife Amelia (1834-1892) was an agent for the Wheeler & Wilson sewing machine company, working out of the family’s store.

At the time of the Raid, Frederick and Amelia were very likely grieving the deaths of their two young daughters. In researching this post, I found the following article in the Lawrence Republican on May 3, 1860: “In this city, on Monday morning, April 30th, ADDIE L., only child of F.W. & Amelia A. Read, aged one year, eleven months and twenty-two days.” I also found, in the Complete Tombstone Census of Douglas County, Kansas, this record of the couple’s second loss: “Died at the residence of Levi Gates in West Lawrence, August 30, 1862, Freddy Rockwell Read, only child of F.W. and Amelia A. Read, aged eleven months.” Both Freddy and Addie were buried in Pioneer Cemetery, now located on the University of Kansas campus. The location of their graves is unknown.

Only the Reads’ youngest child – their son Lathrop – survived to adulthood.

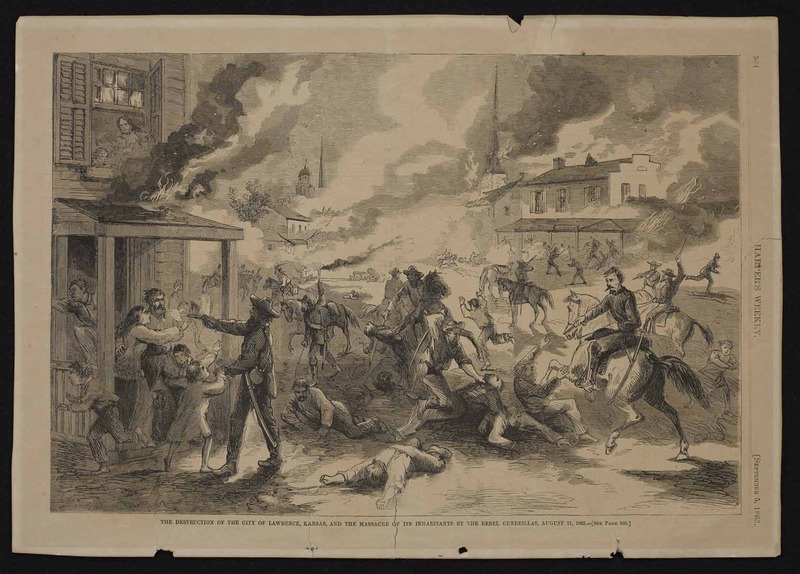

Almost exactly one year after Freddy’s death, the Reads experienced significant losses during Quantrill’s Raid. Frederick escaped physical harm, but raiders looted and burned his store. Amelia was somehow able to save the family’s house from being set on fire, but she couldn’t stop the raiders from robbing the home.

There are multiple published descriptions of the Reads’ home during the Raid. One can be found in The Lawrence Massacre by a Band of Missouri Ruffians Under Quantrell [sic], published in 1865 by J. S. Boughton. Spencer Research Library has a copy of the volume; it’s also available online. Note that this account mentions daughter Addie by name, but it was her sister Freddy who had “died a few months before.”

The residence of F. W. Read was probably visited by more squads than any other place, as it is situated in the heart of the city. Seven different bands called there that morning…The next squad were for stealing, after demanding as they all did fire arms at first, they wanted money next and then helped themselves to whatever they could find. They found in the back side of a bureau drawer a little box containing a pair of gold and coral armlets [elsewhere described as bracelets] used to loop up the dress at the shoulder of their little girl Addie who had died a few months before. Mrs. Read begged very hard that he would please not take them as they had been her little dead child’s and she wanted them to remember her by, the brute replied with an oath “Damn your dead baby, she’ll never need them again.”

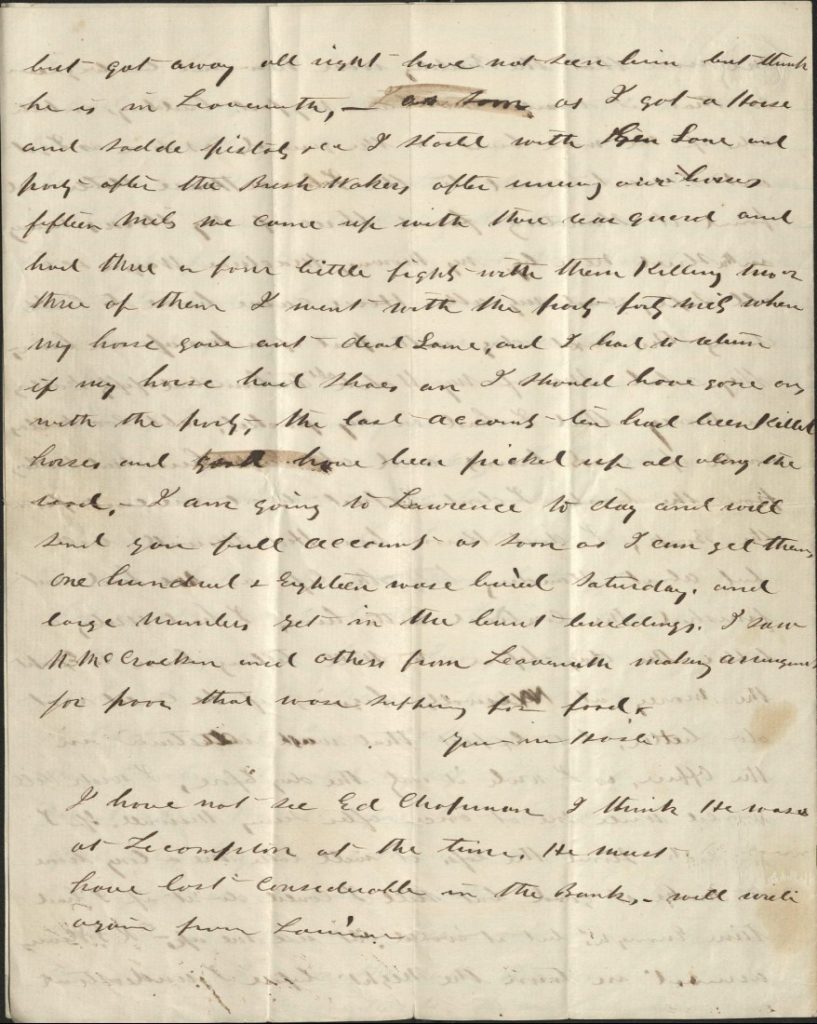

The heartbreaking story of the bracelets and the ambrotype below were the inspiration for this post. The ambrotype is part of Spencer’s Leonard Hollmann Photograph Collection. It’s identified as a post-mortem image of Freddy Rockwell Read, likely because it’s accompanied by a copy of the child’s obituary (quoted above). However, given the information I found while researching this post, I now believe that is incorrect.

The child in the ambrotype looks to be about two years old, the age Addie was when she died. Thus, I believe the child in the ambrotype has been previously misidentified and is the Reads’ oldest child Addie. It’s still unclear who the bracelets belonged to.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services

Caitlin Klepper

Head of Public Services