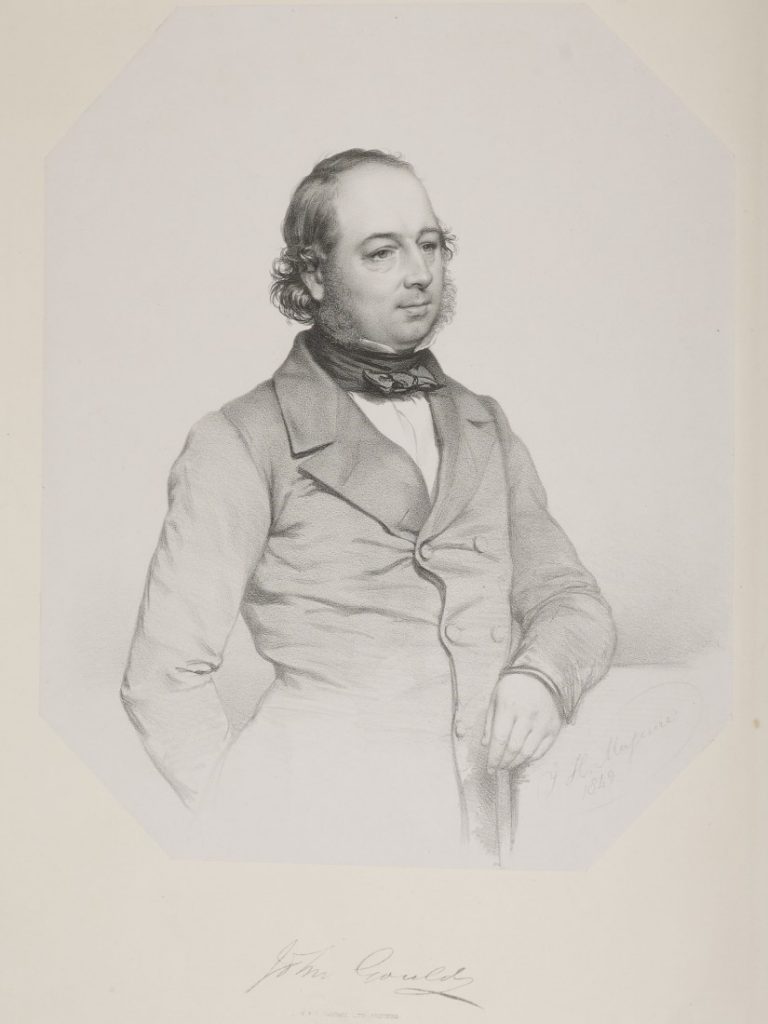

John Gould (1804-1881): Birdman in the Australian Bush

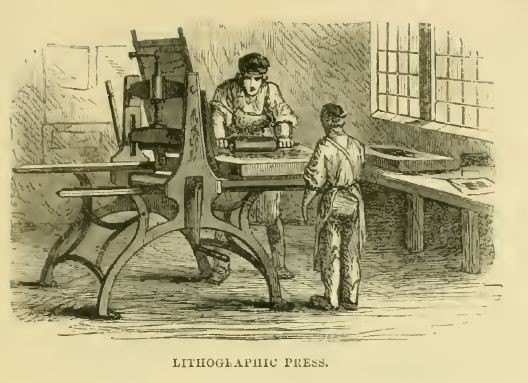

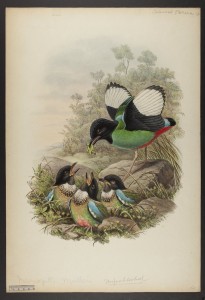

December 22nd, 2020When John Gould set out with his wife Elizabeth and eldest son (three younger children remained in England with their grandmother) in 1838 on the five-month sea voyage from England to Australia, his goal was to observe birds in the wild, collect specimens and enable Elizabeth, an artist, to make drawings for their planned book about Australian birds. Their first stop was Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen’s Land), where the Goulds were befriended by the governor, Sir John Franklin, and his wife. Elizabeth, who was pregnant, stayed with the Franklins and made drawings of plants and animals. Meanwhile, Gould explored the bush in Tasmania and on the Australian mainland in New South Wales and South Australia, including Kangaroo Island. After the birth of another son, the Gould party travelled to New South Wales, where Elizabeth’s brothers, Charles and Stephen Coxen, had settled. Following the Goulds’ return to England in 1840, The Birds of Australia appeared in 36 installments, the first on December 1, 1840 and the last in 1848. Elizabeth had died in 1841, so the later parts were illustrated by another artist, Henry Constantine Richter, working under Gould’s close supervision. The lithographic crayon drawings, printed in black and hand-watercolored by hired colourists, contributed to the success of this landmark early book about Australian ornithology.

Gould also wrote the descriptive text accompanying each illustration with assistance from his accomplished and devoted secretary, Edwin Charles Prince. The comments about many of the birds of southeastern Australia were based on Gould’s own observations. Although John Gilbert, an assistant who accompanied the Goulds to Australia, had supplied specimens and notes about birds from other parts of Australia (before being killed by Aborigines near the Gulf of Carpenteria), the examples discussed here are firsthand accounts that reveal Gould’s keen observational skills, deep interest in birds, and nascent ambivalence toward the killing of birds for sport, food, and scientific collection.

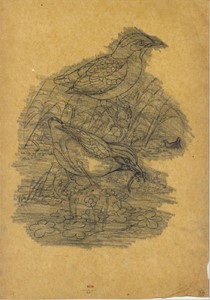

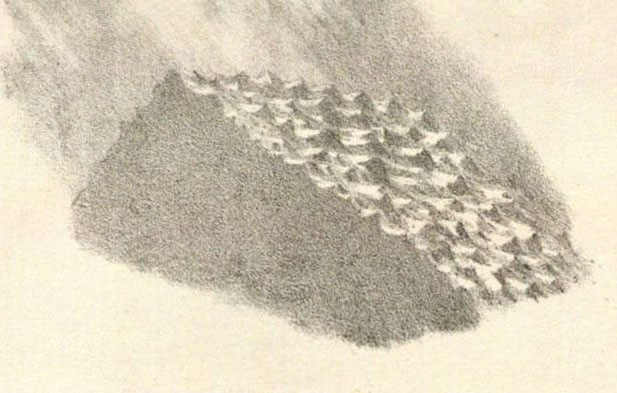

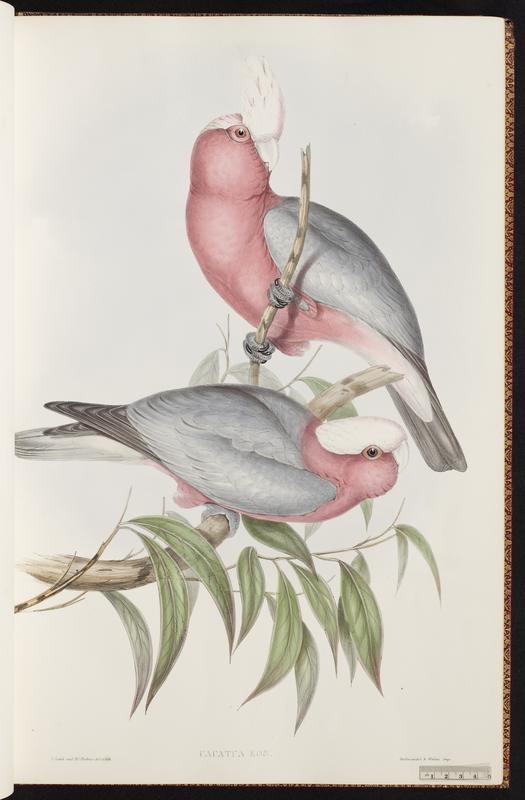

Gould’s text enlivens this static picture of Rose-breasted Cockatoos by describing the breathtaking experience of seeing flocks in motion. “The Rose-breasted Cockatoo possesses considerable power of wing, and like the house-pigeon of this country [England], frequently passes in flocks over the plains with a long sweeping flight, the group at one minute displaying their beautiful silvery grey backs to the gaze of the spectator, and at the next by a simultaneous change of position bringing their rich rosy breasts into view, the effect of which is so beautiful to behold, that it is a source of regret to me that my readers cannot participate in the pleasure I have derived from the sight.”

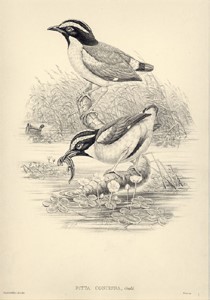

The nesting habits of Australian birds were also intriguing. Gould writes that the Spotted Pardalote’s nesting habits differ from known members of its genus in nesting underground; “availing itself of any little shelving bank that occurs in its vicinity, [it] excavates a hole just large enough to admit of the passage of its body, in a nearly horizontal direction to the depth of two or three feet, at the end of which a chamber is formed in which the nest is deposited. The nest itself is a neat and beautifully built structure, formed of strips of the inner bark of the Eucalypti, and lined with finer strips of the same material.”

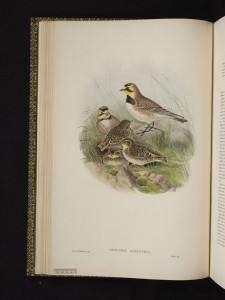

Above ground, Gould was surprised to find that Spotted-sided Finch nests are “frequently built among the large sticks forming the under surface of the nest of the smaller species of Eagles…both species hatching and rearing their progeny in harmony. He observed “little finches…sitting on the small twigs close to their rapacious but friendly neighbor…a Whistling Eagle.”

Some birds could co-exist with European settlers. Gould comments that the Piping Crow-shrike (Gymnorhina tibicen) “…is a bold and showy bird which, when not harassed and driven away, greatly enlivens and ornaments the lawns and gardens of the colonists by its presence, and with the slightest protection from molestation becomes so tame and familiar that it approaches close to their dwellings, and perches around them and the stock yards in small families of six to ten in number. Nor is its morning carol less amusing than its pied and strongly contrasting plumage is pleasing to the eye. To describe the notes of this bird is beyond the power of my pen, and it is a source of regret to myself that my readers cannot, as I have done, listen to them in their native wilds…”

Equally bold but less welcomed by colonists, a raptor, the Allied Kite (Milvius affinis), has a “confident and intrepid disposition [that] renders it familiar to every one, and not unfrequently costs it its life, as it fearlessly enters the farm yard of the settler, and if unopposed, impudently deals out destruction to the young poultry, pigeons, &c. tenanting it. The temerity of one individual was such, that it even disputed my right to a Bronze-winged Pigeon that had fallen before my gun, for which act, I am now almost ashamed to say, it paid the penalty of its life; on reflection I asked myself why should advantage have been taken of the confident disposition implanted in the bird by its Maker, particularly too when it was in a part of the country where no white man had taken up his abode and assumed a sovereign right over all that surrounds him.”

While “a most delicate viand for the table,” the Partridge Bronze-wing (Geophaps scripta) is less endangered due to its isolation. “It is to be regretted that [it] should be so exclusively a denizen of the plains of the interior that it is available to few except inland travelers…It is withal so excessively tame, that it is not unfrequently killed by the bullock-drivers with their whips, while passing along the roads with their teams.”

Gould’s regret for the predicted disappearance of the Adelaide Parakeet (Platycercus adelaidiae) did not curtail his specimen collecting. “This beautiful Platycercus…may in a few years be looked for in vain in the suburbs of this rapidly increasing settlement [Adelaide], as it…is even now much persecuted and destroyed by the newly arrived emigrants, who kill it either for mere sport or for the table; for, like the other Platycerci, all of which feed on grass seeds, it is excellent eating. It was only by killing at least a hundred examples, in all their various stages of plumage, from nestling to the adult, that I was enabled to determine the fact of it being a new and distinct species.”

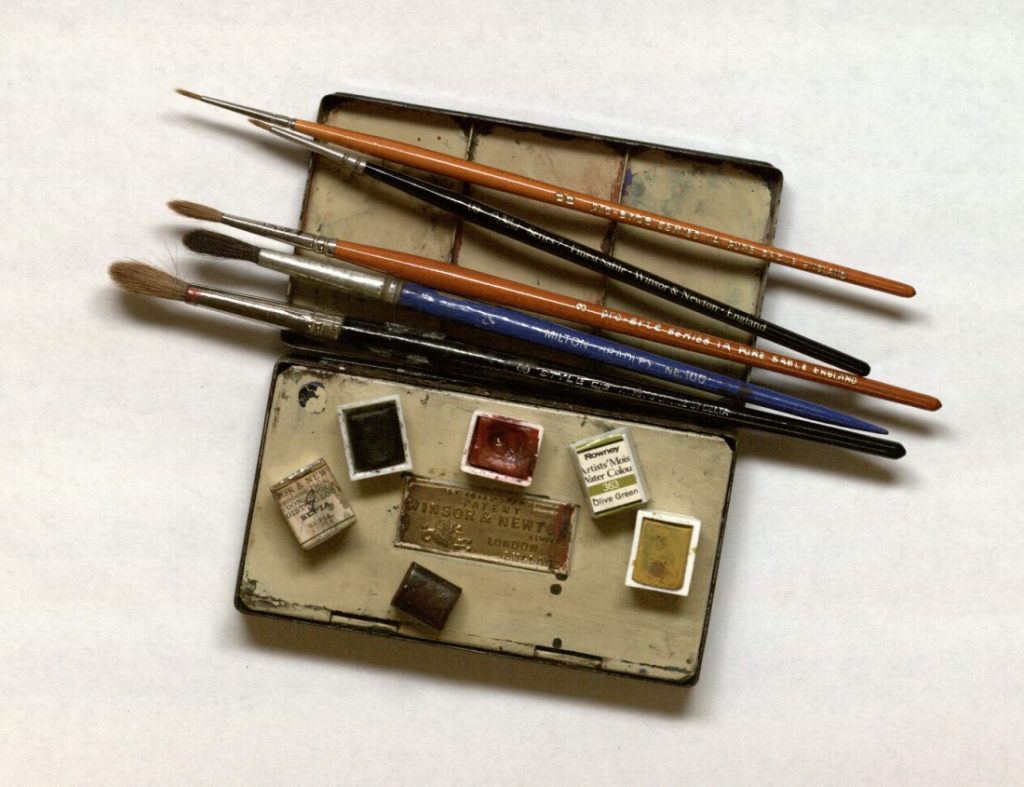

We may disagree with him, but Gould was a man of his times, and his views are part of the history of ornithology. Although the science of ornithology has since moved on, aided by technological innovations not dreamed of in Gould’s lifetime, the artistry of the beautiful illustrations in his books still attracts modern viewers. These illustrations allow us to see the birds through the eyes of Gould and his artists, and it is equally worthwhile to read Gould’s eloquent written observations about them. The John Gould Ornithological Collection, accessible at the University of Kansas Libraries website, offers the opportunity to pair pictures and descriptive text while reading digitized copies of Gould’s books on the Internet. A nearly complete set of John Gould’s publications, along with about 2000 pieces of preliminary art from his workshop, was bequeathed to the University of Kansas in 1945 as part of Ralph Nicholson Ellis, Jr.’s natural-history library. The Gould books and artwork were digitized with funding support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Karen Severud Cook

Special Collections Librarian

Kenneth Spencer Research Library

Hugh Orr

Member, Royal Geographical Society of South Australia