In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

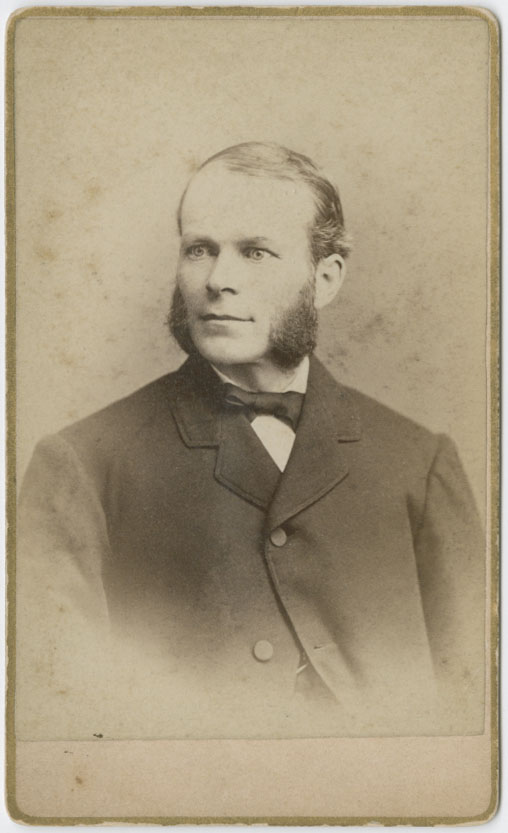

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

Today’s first entry catches up with Forrest’s story and includes his letters from the previous week. Highlights include his instructions on how to swim (“always swim in the water“) and comments about a newspaper article predicting the “world coming to an end…this noon” (“I have no opinion to offer – it is the least of my troubles”).

Click images to enlarge.

Friday, July 27, 1917

Dear Marie,

I am going to be a Radio operator in the Company A, 6th Field Battallion, Signal Corps. Will study at Fort L. School. Will write Sat. or Sun.

Yours,

Forrest

Address

Forrest W. Bassett

Co. A, 6th Field Battalion

S.C.

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Click image to enlarge.

Sunday, July 29, 1917

Dear Marie,

Are you have a good time at home? I would like to be there for a few days. Sure miss the good times we had. Unless something serious turns up I will not see Beloit again until the end of the war. This is a fine place here. We have a fine bunch of fellows and good officers. I wish you would write. I only got your first letter. Tell me all about everything at home.

Your,

Forrest.

Wed. August 1, 1917

Dear Marie,

Your four letters from J. B. [Jefferson Barracks] are here ok. They sure stirred up some “happy feeling” alright. I wish I could have one every day. You would write that often if you know how glad I am to get them. We are getting the heavy work now and are pushed from rising call till bedtime. Today we were up at 5:15 and there were very few spare moments. We drilled until 8:00 tonight. We have regular infantry drill on top of the signal work. In the latter we have buzzer practise like you and I used to do and ‘wig-wag’ signaling in the field.

There are about six different means of communication that we must master. My partner in ‘wig-wag’ practise told me (by the flag signals) that he was a Minnesota man, head been a train dispatcher and had served in the army five years. He started to talk by asking me if I had heard the report about the world coming to an end. My arm is dead tired from waving my signal flag and I can hardly write. I guess I am the youngest man here. Almost all are over 25. They are starting classes in French language tonight. Our training is being rush as fast as possible. I went to the sergeant and asked him why I was assigned to the Radio Corps and he referred me to the Company Commander. I saw him but he told me to discuss it with the Battallion commander. I didn’t push it any further but last night the sergeant called me in the orderly room and questioned me pretty thoroughly on my past experience. I may get in the aerial photography yet. However I am well pleased with what I have now. This “stuff” is also a little safer than photography from aeroplanes.

They keep us on the jump but it certainly is interesting.

Mother says you look like a girl of 18 with you hair done up. I almost hate to think of you any different than you were when I last saw you. I am afraid after all that you will change in more ways than one before I come back. Please keep that diary and don’t skip even a day. Put down what you think as well as what you do. I will send you a picture when I get one of you, maybe. Don’t hesitate to tell me if there is anything I have that you can use.

Yours, Forrest

Tell you mother to write some more like her first one.

Believe me I sure enjoyed it.

No more time tonight but will write again tomorrow.

I got your letter with the world coming to an end clipping this noon. I have no opinion to offer – it is the least of my troubles.

Thursday, Aug 2, 1917

Dear Marie,

I got two letters from you and one from Blanche today. Lauretta is a good kid alright; I’m glad you like her. I wish I were there to play “Sailor Boy’s Dream” with you. I would probably dutch it all up but we sure had some good fun that way. I’ll never forget the time we ate those cherries on the porch. Gee, but I’ll be glad to get back to you again but I’m not sorry that I’m making these sacrifices. I only hope you won’t change from the same big little-girl that you were. Please write as often as you can, and keep your diary.

I will do the best I can, but there are many odd little jobs to take care of after all the regular work & drill is done. We had an hour of wig-wag practice this morning and I talked with an Iowa railroad telegrapher. The ‘wig-wag’ is a method of talking in the field by means of flags. We always start up with conversation and tell about ourselves. This afternoon I practiced with a railroad telegrapher from Wisconsin. In the morning we had an hour of drill at fancy marching. We also had two hours of drill at pitching shelter tents. This afternoon we had a buzzer practise and our third lecture on doing guard duty. We have good officers here and everything is as good as one could expect. I pity those fellows that had to remain at Jefferson Barracks several weeks before being sent to their regular post. I may be transferred from here. This noon the sergeant told me to report to the commanding officer of the battalion. The latter asked me a lot of technical questions about lenses and cameras and I know I answered them correctly. He dismissed me without dropping any hints so I don’t know how I’ll come out. The nearest first class aviation camp is at Texas. They are going to start one in Kansas City too.

I hope I can see you before we leave. Maybe we can dope out some way. My friend George Stock started his French under a French lady last night. I am going to start next Monday but am going to try a University professor. This is not required. I don’t know what it will cost. The govts pays Sig. Corps men $30 a month and a $60 a year clothing allowance. We have to be careful and dress neatly and in clean clothes all the time. We have all of every Friday afternoon off to prepare for Saturday morning inspection. Believe me it’s ticklish business to get by the inspection officers. One’s hair has to be kept cut close but I am always going to keep mine that way, even when I get home. I only have to comb it about once a week when I used to do it at least three times a day. Suppose I’ll have to get acquainted all over again when you start wearing your hair done up and your heels upon spools. Mother gave you straight tip about finger nails and will power. Did you notice how Lauretta bites hers. No you didn’t. Believe me if no one does anything worse than that, he needn’t worry about the end of the world. Did you and Lauretta go swimming? I told Mother to get the waterwings out for you.

Once more:

- Always swim in the water.

- Hold your breath until you learn to time your arms with your legs and keep afloat for a few strokes.

- When you do breathes, always breathe out thru the nose and in through the mouth.

- Be sure to time your breathing and every movement of your legs and arms. When this becomes instinctive (ouch) you can go to sleep on the job.

- Take your time, and go easy.

Do you remember how I used to fuss about that? I sure do wish I could be with you. Each man had to swim a hundred yards in order to pass examination here. There are a few that will have to do some tall practising. Lot of them are 30 & 35 and never saw anything but a tub for 15 years.

I suppose the “sullies” will get us if we don’t watch out, but we may not even have to cross over to France. Things to worry about. The most I’ve got to worry about is a little brown eyed girl. I left out the “big” this time. Gee I don’t want you to be all grown up when I get back. But I don’t care if you are if something else doesn’t change.

Your’s, Forrest.

You will find any negatives you want in my negative file box.

Help yourself.

I wish I had printed one of you in the canoe and by the cherry tree.

Write soon and talk to me as if we were together. Please.

Monday, Aug. 3, 1917

Dear Marie,

I guess you don’t really know me after all. When you were in my arms, couldn’t you see in my eyes how much I care? How can I tell you in my letters that I will always love you and make you feel that I am honest and sincere? I have had lots of time for good sober thought, here, and I know it is your high character and big, warm heart that has won me so completely. There is not another girl on the map that would make me look twice after knowing you so well. Little girl, even if you go through High School and find out that you can’t really love me, the influence you have had on me will have done its work and I will never be able to pay the debt I owe. Don’t believe all the good things that sister says of me. You know how it is. I didn’t have any idea Blanche did not know how much we are to each other.

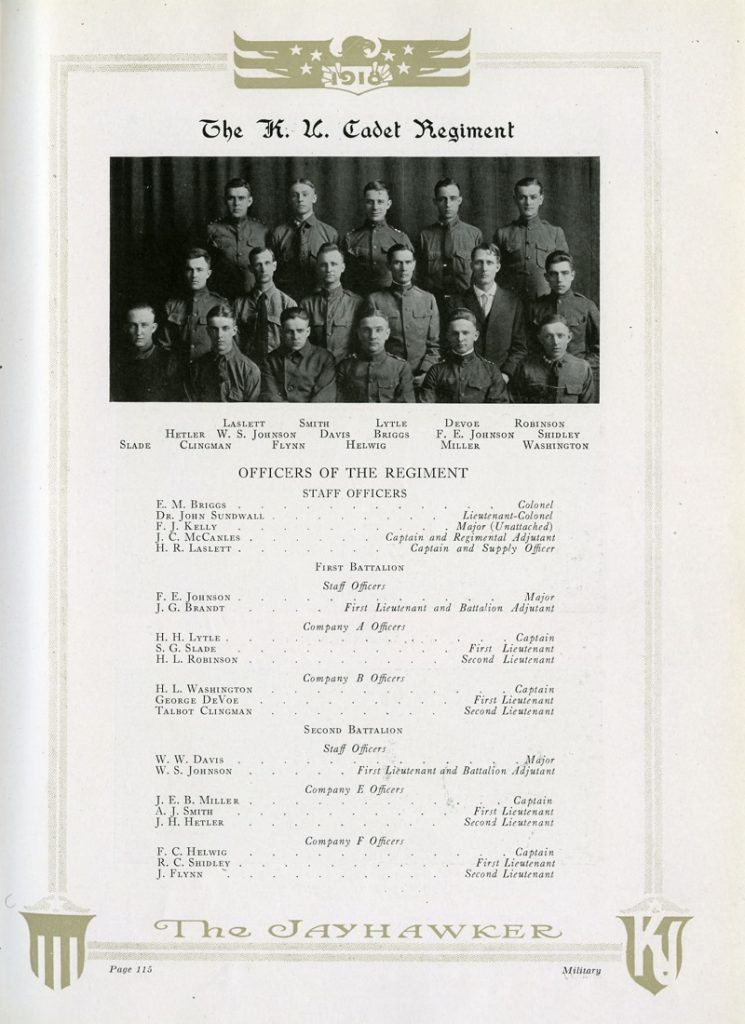

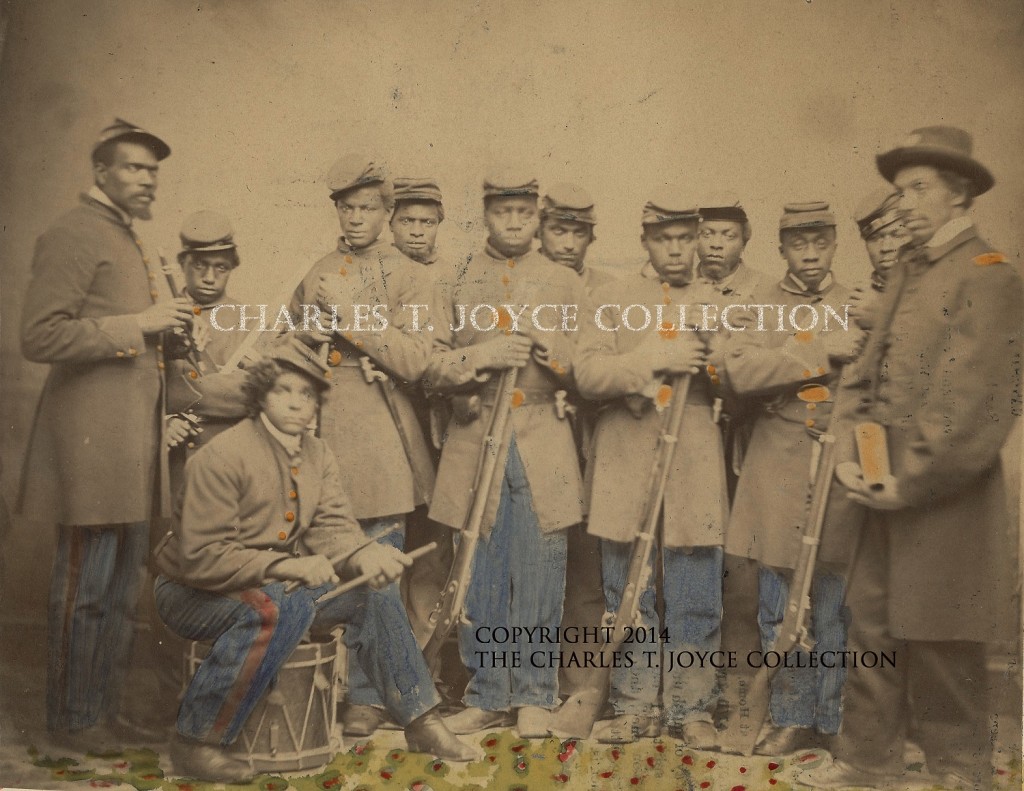

Marie, even if I can’t have you, I will always think of you as a big warm hearted girl that understood, and trusted me so I couldn’t do very wrong. I hope I can have your pictures soon. Here is a post card of the Sixth Field Battalion on muster day. I am in the front rank with the arrow at my feet. I am wearing leather leggings and the men on each side have on white leggings. Now can you find me? All the men in the picture are in the 6th FB S.C. Some are telegraph men, some are telephone, but Co. A is all radio. We had quite an interesting period of radio practice this afternoon. Within fifty feet of our station there was a class of artillery officers with a big gun and range finding instruments. Last week we saw the engineers build a pontoon bridge across the small lake at the foot of our hill. I wish I could write to you oftener. Sunday I worked all day from 6 o’clock AM til 6:45 PM and after I had scrubbed my leggings and taken a shower, I felt so tired that I hit the hay.

We sure will hike together if you really like it, and I hope you will. We had an inexperienced drill master this morning and he Dutched up everything. He would give his command of execution on the wrong count and then get sore because we got our feet all tangled up. Our regular sergeant was taking a special examination for officers.

Last Saturday at retreat roll call he asked if anyone in the ranks knew anything about the theory of gas engines. This stuff happens to be my specialty so I had the privilege of explaining how gasoline is converted into power in 2 and 4-cycle motors.

It was deep stuff but I got away with it OK. You see our wagon set generator for the field wireless is run by a four-cylinder gas engine, and that was part of his exam.

When you go back to school, will you write to me about your work and let me help you! Well there goes tattoo, which mean “lights out.”

Yours,

Forrest

I see I am a month behind on my date.

Click images to enlarge.

Monday, August 6, 1917

Dear Marie,

Your letter of Friday the third was certainly a gloom chaser. I did not get one yesterday nor today. I suppose you and Lauretta are on the skip every evening, but don’t forget to write and tell me everything – and be sure to keep your diary. I don’t care if you do wear your hair up, now. I would like to see you that way.

Here’s hoping Chicago will not make you forget one whose every thought is of you and you. I am going to keep that Friday letter with me always. It’s that thought of you that makes me put in my best licks every minute. I hope I will see you by the end of the month. Every one seems to think we leave for Monmouth, New Jersey about Sept. 15th.

About 70 men came in from San Francisco yesterday. I heard a company sing “On Wisconsin” and give some University yells, and believe me it sounded great. I am still in doubt about the aerial photography, but the sergeant said I may be called for any minute. This Radio Co. is a fine bunch and I will be satisfied to stick with it.

We had a lecture on Field Wireless sets, and one on military law today. I can receive about ten words a minute in the European code and am picking up fast. I am going to take my first French lesson tonight, and will have to close now. Be good to me and write.

Yours,

Forrest

Meredith Huff

Public Services