In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the Kansas Territory for settlement, destined to become a free or a slave state by popular vote. Conflict between settlers from slave-holding Missouri and anti-slavery New England inspired the nickname “Bleeding Kansas.” Although a free-state Kansas constitution was adopted in 1861, the Civil War prolonged the strife until 1865.

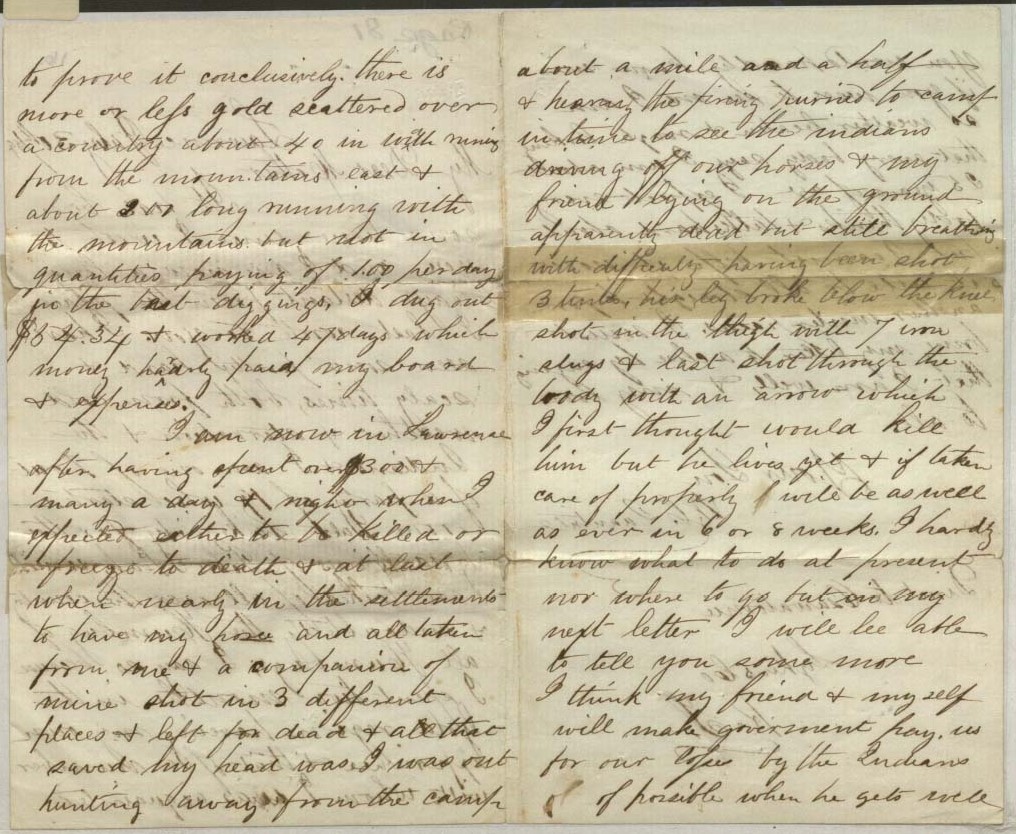

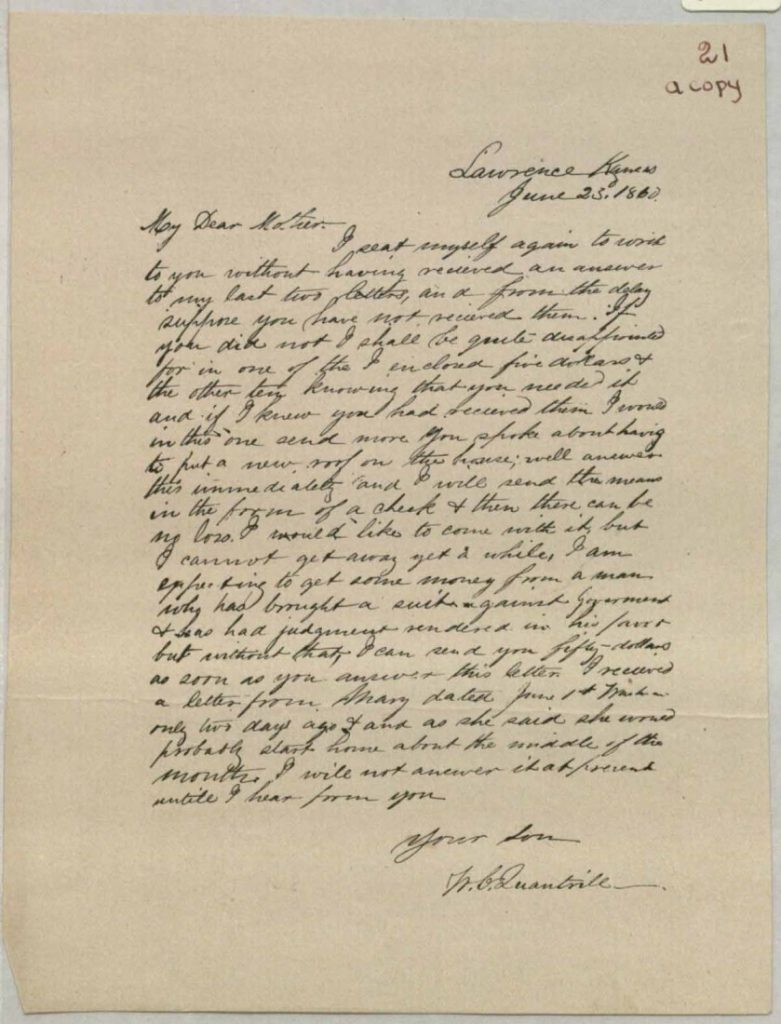

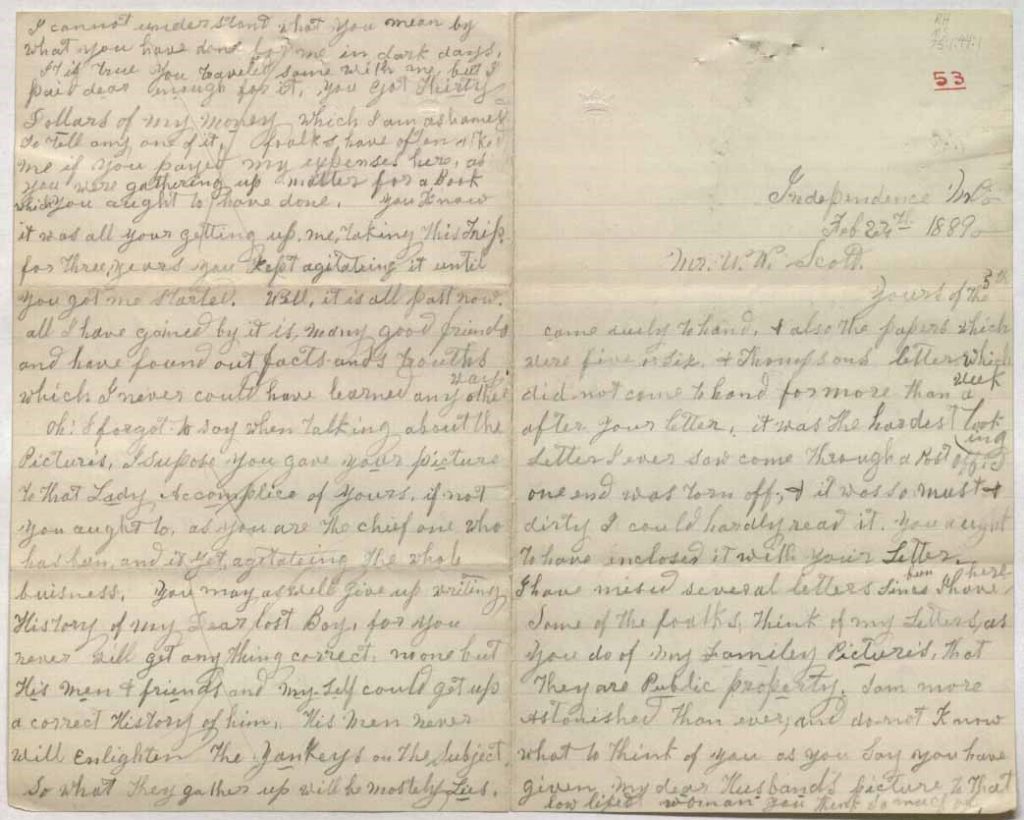

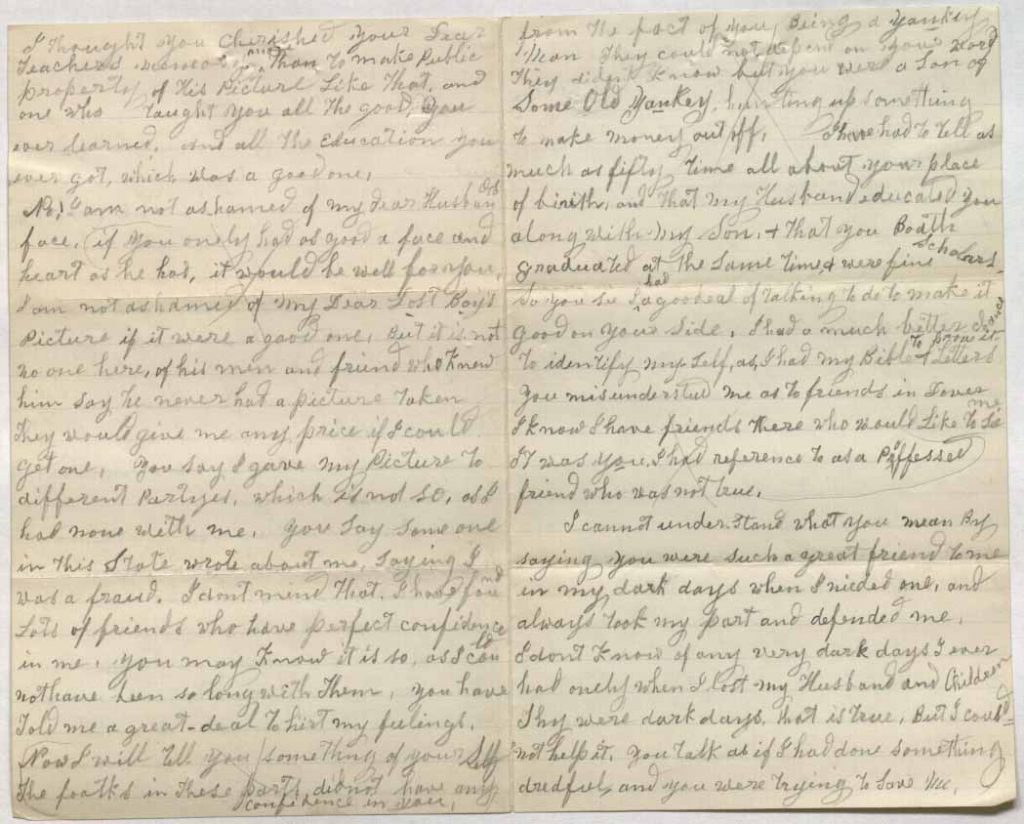

Among the first Kansas settlers were land surveyors needed to lay out land claims and towns. Albert Dwight Searl (1831-1902), a civil engineer from Massachusetts, reached the Lawrence town site in September 1854 with the second group of settlers.

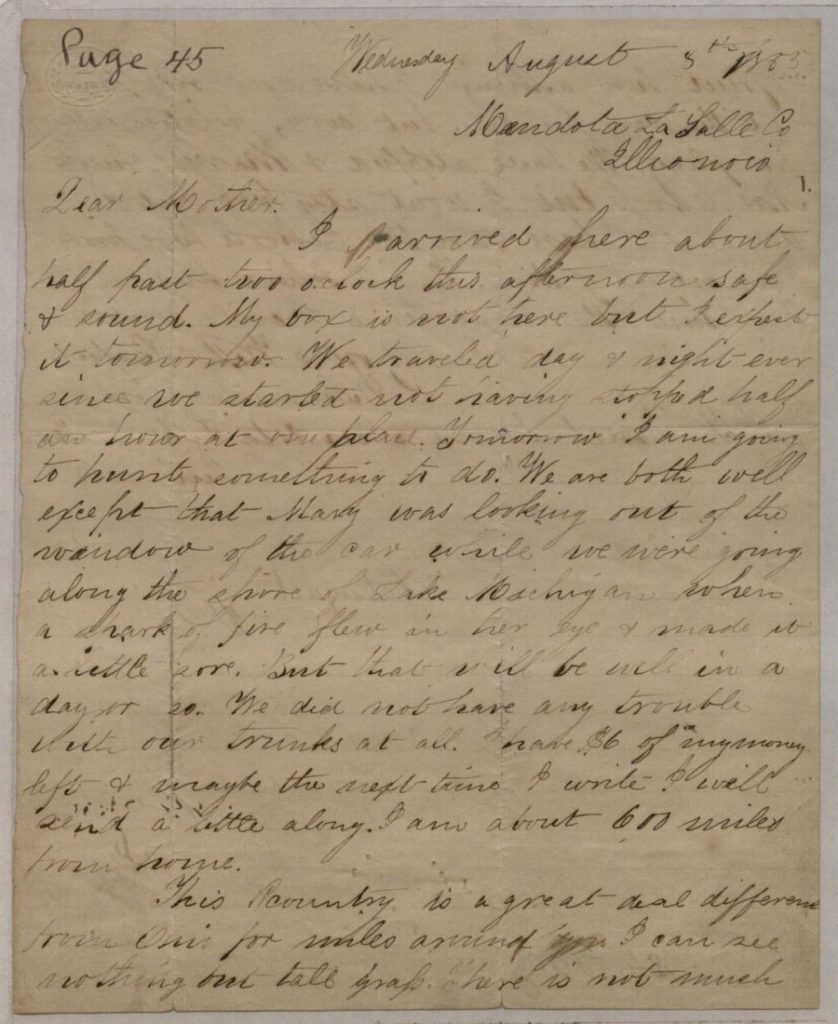

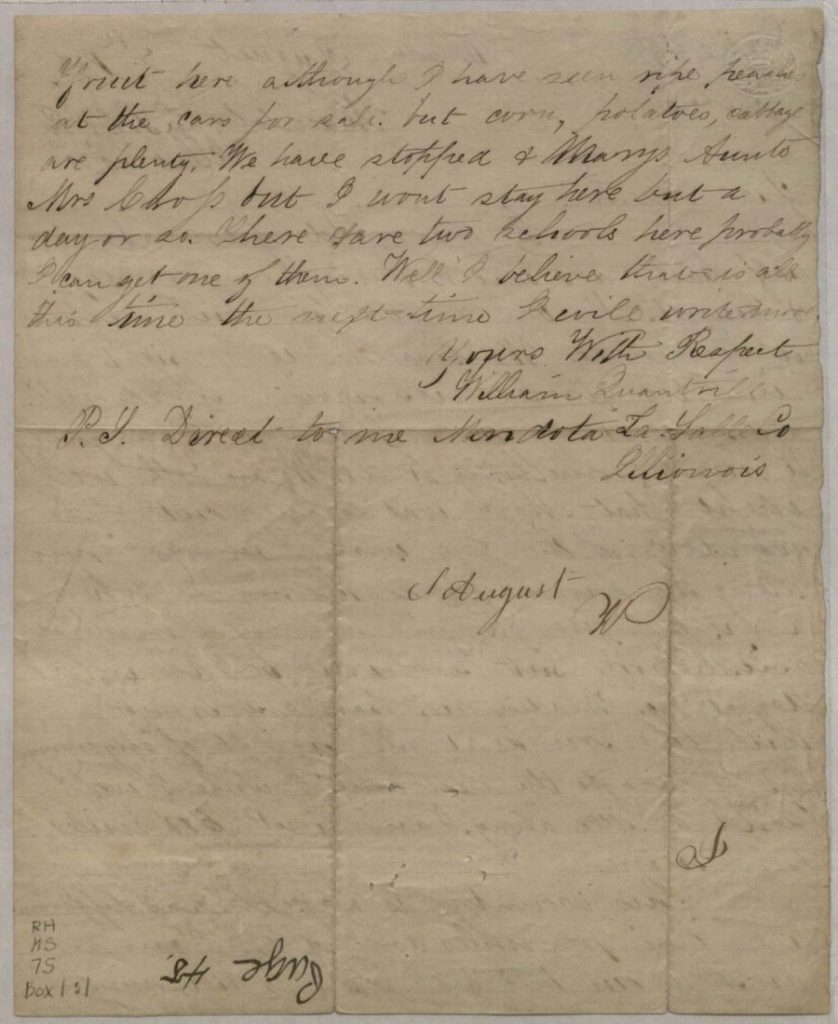

The first group had arrived a month earlier and roughly laid out land claims. As one settler wrote: “After pacing off a half mile square, we drive down a stake at each of the four corners; on one of the stakes we write: I claim 160 acres of the lands within the aforesaid bounds, from the date of claim. This is then copied and taken to the register and recorded.” After Searl arrived they pooled their already staked claims, and he began “to survey farm lots in number equal to the claimants in both parties.” When Searl and an assistant surveyed the Lawrence town site in September, the tall prairie “grass wore out their pants to the knees till they had to cover them with flour sacks for protection.” Searl “established the meridian line …by setting a row of lights up and down Massachusetts Street in the evening and running a line by the North Star.”

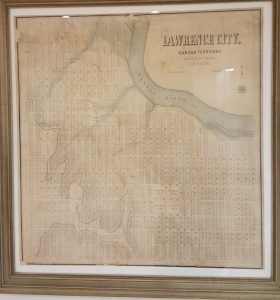

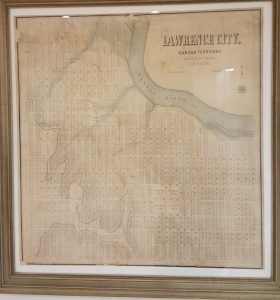

Searl’s plan of Lawrence arrived from the Boston lithographic printer in January 1855. “Map of Lawrence City, Kanzas, Surveyed in Oct. 1854 by A. D. Searl,” which is on display in the Spencer Research Library lobby. Click image to enlarge.

_

An 1869 bird’s eye view shows Lawrence expanding to fill the grid laid out by Searl.

Ruger, A. Bird’s eye view of the city of Lawrence, Kansas 1869. [Place of publication

not identified: Publisher not identified, 1869]. Call Number: RH Map R140. Click image to enlarge.

He also laid out Topeka, Osawatomie, Palmyra and Prairie City. An 1855 newspaper article said, “Mr. Searl … seems to us well qualified for getting up a complete map of Kansas, and we hope he well [sic] be induced to prepare one immediately after the completion of the surveys.” Soon the Territorial Legislature hired Searl to undertake the map project with a partner, Edmund Burke Whitman. They spent a year traveling the Kansas Territory. In April 1856 the local newspaper praised their draft map for including “all rivers and creeks, with their names, main-travelled roads to the various sections, post offices, towns, trading posts, forts, mission stations, Indian reserves, noted mounds, guide meridians, base and township lines.” In May 1856, before the map was published, pro-slavery raiders attacked Lawrence and burned down the Eldridge Hotel, the Free-State headquarters. The views on Searl and Whitman’s 1856 map of Kansas show the Eldridge Hotel newly built in April and as burned ruins after the May raid.

Searl described damage to his own nearby office: “I had among my papers notes of surveys of different parts of the Territory; … I also had notes of the surveys of Lawrence and Topeka … The transit instrument was injured, the axis of the telescope was bent, and the screw that secures the axis to the upright pieces that support the telescope was broken and rendered the instrument unfit for use; … The door of the office was broken open, some window lights broken, two chairs injured; the drawing table besmeared with whisky and sugar, and the house dirtied up by oyster cans, &c.”

Undeterred, Whitman and Searl opened their Emigrant’s Intelligence Office in Lawrence in May 1856. As general land agents they offered to help clients seeking land in Kansas. According to their prospectus, Searl, who had laid out the city of Lawrence, could “trace back all the lots to their original holders, and show the valid titles.” They were also “prepared to lay out town sites and to survey farm claims, – to negotiate the sale and transfer of town property generally, – to investigate the validity of titles, – to superintend the erection of buildings, and to act as Agents for the care of property owned by non-residents.” The partnership was brief, though, and Burke left Kansas in 1858.

However, Searl, his wife and two children remained in Lawrence. In November 1855 he joined a Free-State Army unit, the Kansas Rifles No.1. Short in stature like most of its members, Searl proposed renaming it the Stubbs. The Stubbs saw much action during 1856. In 1861 Searl joined the 8th Kansas Volunteers as a private, later transferring to the 9th Kansas Cavalry and mustering out as a captain in 1865.

From 1866 to 1871 he supervised the construction of a railroad line from Pleasant Hill in northern Missouri to Lawrence, Kansas.

In 1868 Searl and William Fletcher Goodhue, a younger civil engineer also employed in Kansas railroad construction, undertook a detailed map of Lawrence. A newspaper article said the map would measure 4’4” x 5’10” and cover “three miles square, or nine miles of the country in and about Lawrence.” The margins would include 25 to 30 representations of public buildings, businesses, and the better class of private dwellings. Holland Wheeler, then Lawrence City Surveyor, saw and approved a draft. Goodhue was supposed to oversee the lithographic printing, but errors in numbering city lots occurred when copying the map at the printer. Searl rejected the printed maps sent to Lawrence in August 1870. The defective maps were turned over to a local bookseller. Attempts to use the map in land transactions attracted severe criticism of its errors. Wheeler, Searl, and Goodhue responded in print, defending their work and laying the blame on the printer.

In 1866 Searl and Almerin Tryon Winchell, former manager of the Eldridge House Saloon, became partners in a Lawrence billiard parlor and saloon. Still advertising in 1871, they had ceased business by 1875.

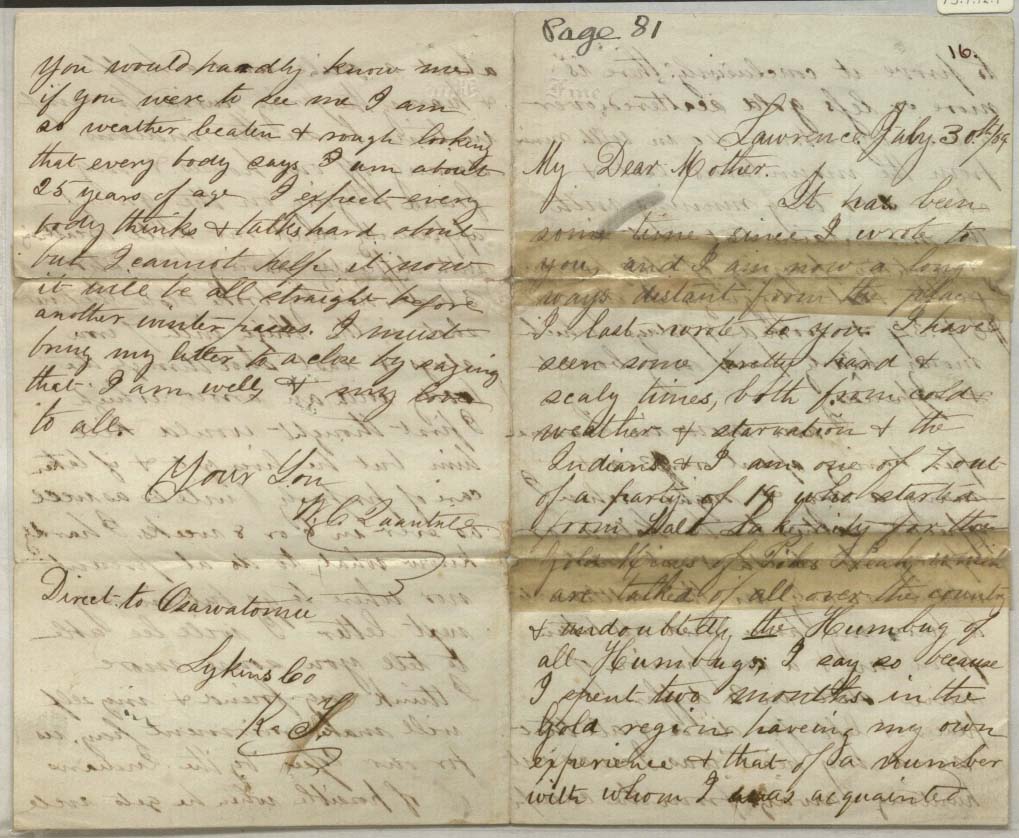

From 1874 to 1875 railroad work took Searl to Ohio. By 1877 he was surveying the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad in Colorado. He also undertook Colorado mining ventures. An 1878 visitor commented that the “indefatigable A.D. Searl… and his lop-eared pony have traveled nearly one thousand miles since he came out. … He looks as tough as rubber.”

However, Searl’s family remained in Lawrence, and he returned often. During one visit in July 1881, friends surprised Searl at his Lawrence home to celebrate his 50th birthday. In 1883 his daughter was married in Lawrence, but by 1890 Searl and wife were living in Leadville, Colorado with their children and grandchildren. When Searl died there in 1902, though, his final wish was for burial in Lawrence.

Karen S. Cook

Special Collections Librarian

To learn more and consult citations, please see Karen’s longer article on the subject:

Cook, Karen S. “Partisan Cartographers During the Kansas-Missouri Border War, 1854–1861” in: Liebenberg E., Demhardt I., Vervust S. (eds) History of Military Cartography. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography. Springer, Cham. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25244-5_14