In Commemoration: Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965

March 9th, 2015This weekend’s three-day commemoration of the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday” recognized one of the pivotal events of the Modern Civil Rights Movement. The occasion drew President Barack Obama, the First Lady and their daughters, former President George W. Bush and Mrs. Laura Bush, as well as a delegation of bipartisan Congressional representatives to Selma, Alabama.

On Sunday, March 7, 1965, about 600 civil rights activists marched in silence from Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama for the Montgomery state capitol building to memorialize the shooting death of Jimmy Lee Jackson by a state trooper at a peaceful voting rights rally in Marion, Alabama and to protest against the intransigent opposition to African Americans registering to vote. The opposition to voting rights was especially strong in Selma, Alabama, where half of the population was African American and had not been allowed to vote since the late nineteenth century. Immediately after crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the marchers were halted by heavily armed state troopers and local police who ordered them to turn back. When they refused, the troopers and police, in full view of news media and other photographers, mercilessly beat and tear-gassed the marchers. Today, this tragic event in our nation’s history is often referred to as “Bloody Sunday.” A week later, in a televised speech, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked for a voting rights bill, and on August 6, Congress passed the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Spencer Research Library’s Kansas Collection includes sources that document the region’s support for Bloody Sunday’s civil rights workers and their efforts. We share a selection of these documents.

ITEMS FROM THE AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE COLLECTIONS

The Wichita Chapter of the NAACP was an early leader in the Modern Civil Rights Movement’s strategy of breaking down the color line through non-violent, direct action. The Chapter’s Youth Council organized the movement’s first lunch counter sit-in on July 19, 1958. A month later, the Youth Council in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma conducted their sit-in.

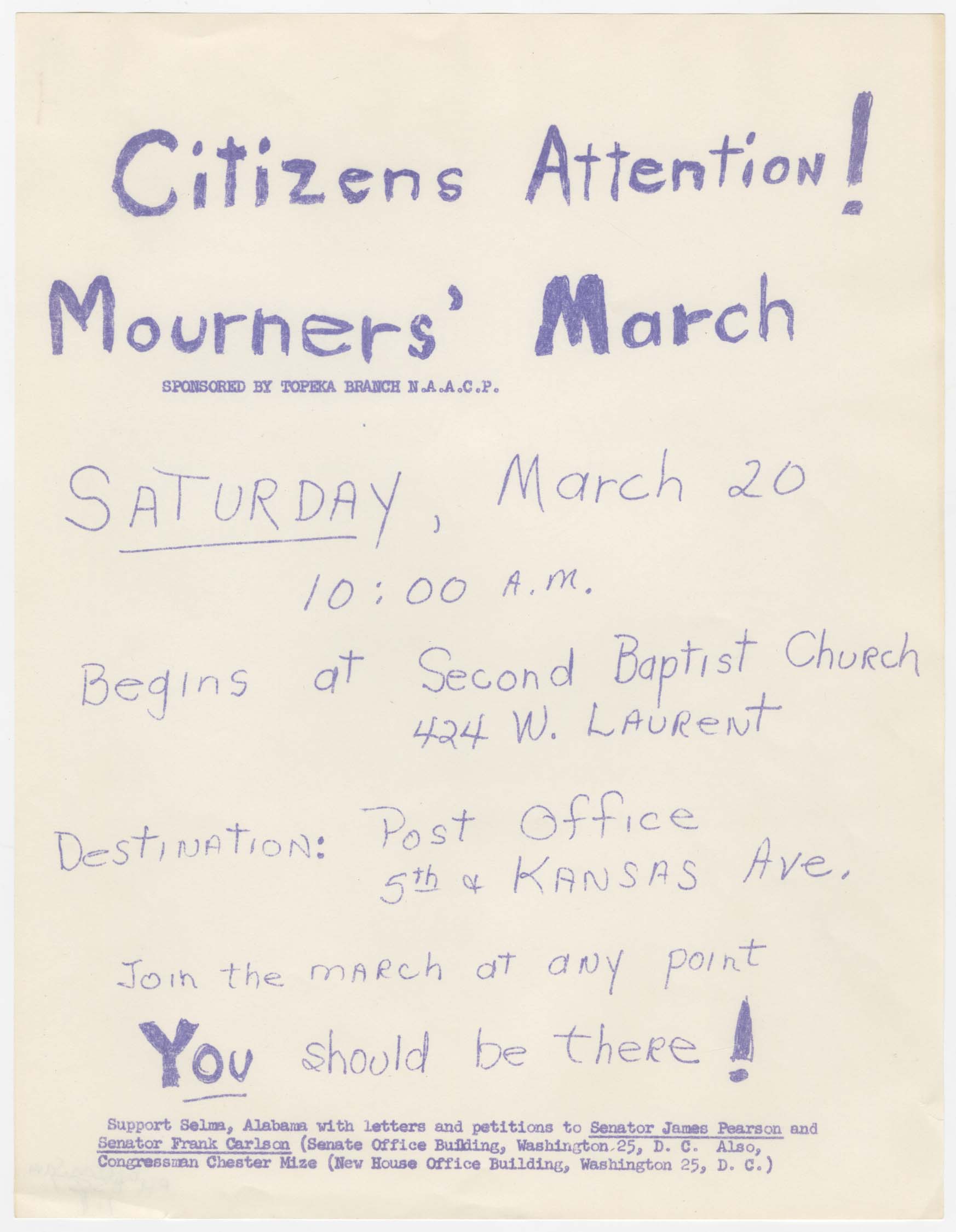

On March 20, 1965, the Topeka Branch of the NAACP organized and led a Sympathy March for the civil rights activists in Selma, Alabama.

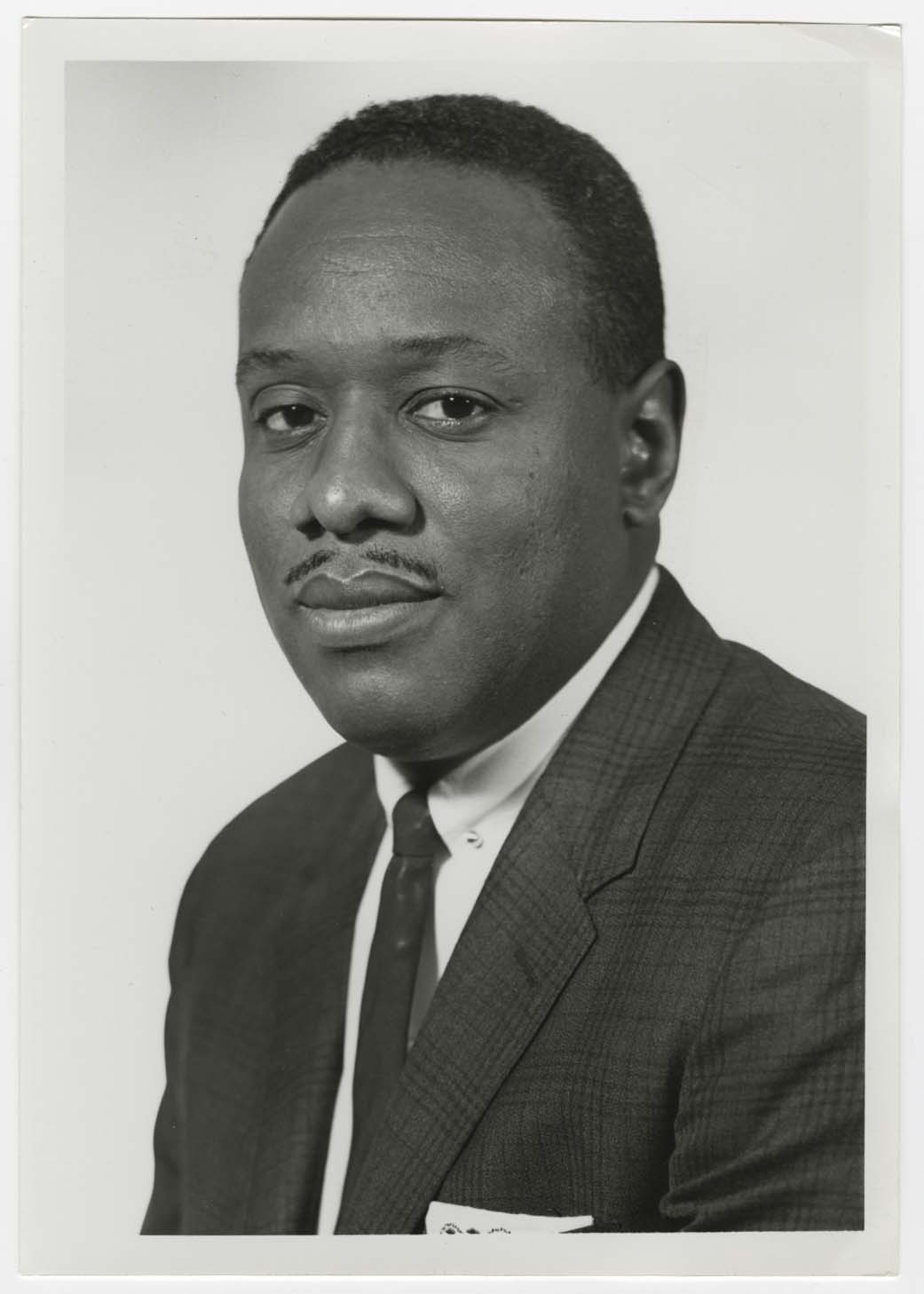

Samuel C. Jackson served as the president of the Topeka Chapter of the NAACP, which had been first established in 1913. Born in Kansas City, Kansas, Jackson earned his law degree from Washburn University Law School and was a WWII veteran. During the fall of 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him to the first U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Four years later, he was appointed General Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development by President Richard M. Nixon.

Photograph: Samuel C. Jackson portrait. Samuel C. Jackson Collection, Call Number: RH MS-P 557, Box 1, Folder 4.

Click image to enlarge.

The Topeka Branch of the NAACP distributed this flyer to mobilize community participation and support for the Sympathy March.

Citizen’s Attention flyer. Samuel C. Jackson Collection.

Call Number: RH MS 557, Box 1, Folder 11. Click image to enlarge.

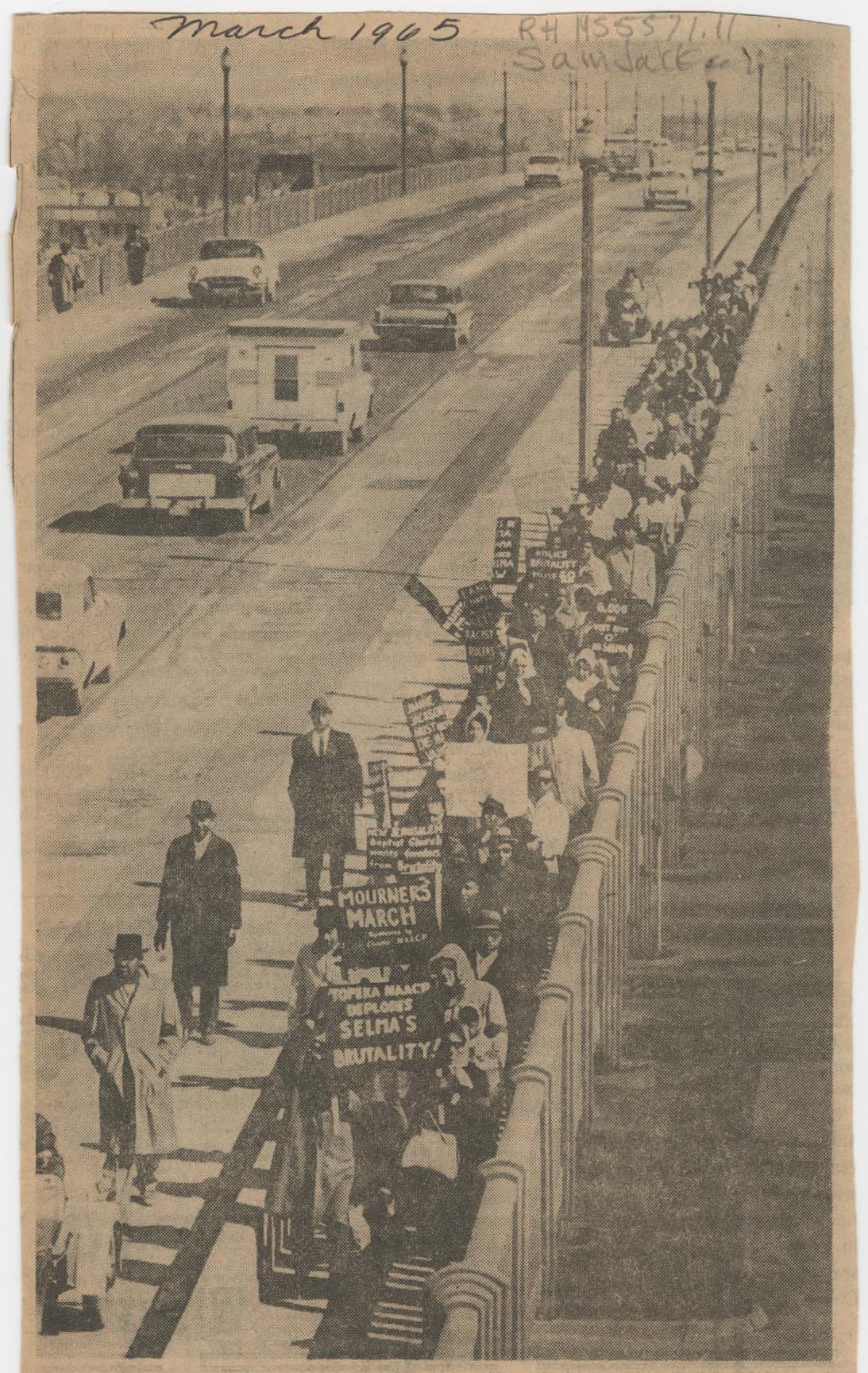

On Saturday morning, March 20, 1965, about 150 marchers began their journey from Second Baptist Church on 424 N.W. Laurent Street in Topeka, Kansas and walked across the Topeka Avenue Bridge, wearing black armbands and carrying signs that read “Topeka NAACP Deplores Selma’s Brutality,” “Mourners March,” and “Police Brutality Must Go.”

Newspaper clipping of “Topeka Rights March.” Samuel C. Jackson Collection.

Call Number: RH MS 557, Box 1, Folder 11. Click image to enlarge.

The Sympathy March continued through the streets of Topeka, Kansas.

Civil Rights Marchers. Topeka, KS, 1965. J. B. Anderson Collection.

Call Number: RH MS-P 1230 Box 1, Folder 31. Click image to enlarge.

When the Sympathy March reached the downtown area of Topeka, about 100 more participants joined them as the demonstration moved toward South Kansas Avenue to the Topeka Post Office where they placed in the mail hundreds of letters and petitions to the Kansas Congressional Delegation, urging them to support upcoming civil rights legislation.

Sympathy March, Topeka, March 1965. J.B. Anderson Collection.

Call Number: RH MS-P 1230 Box 1, Folder 31. Click image to enlarge.

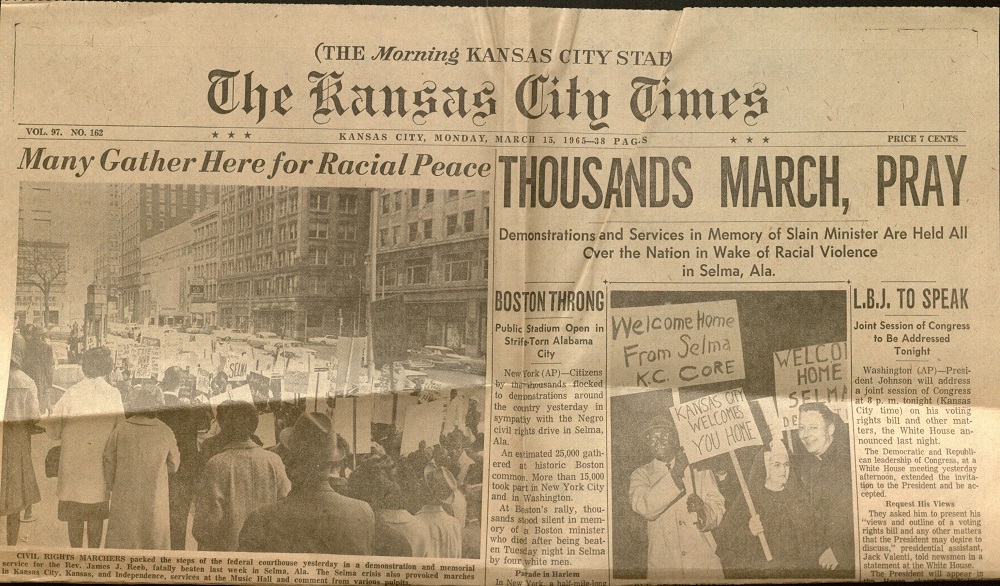

In the Greater Kansas City area and in Independence, Missouri, local chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the NAACP led silent marches throughout the day on Sunday, March 14, 1965. More than 1,200 people participated in these demonstrations.

Greater Kansas City Marches. March 14, 1965. Greater Kansas City Council on Religion and Race Collection.

Call Number: RH MS 786, Box 8, File 12. Click image to enlarge.

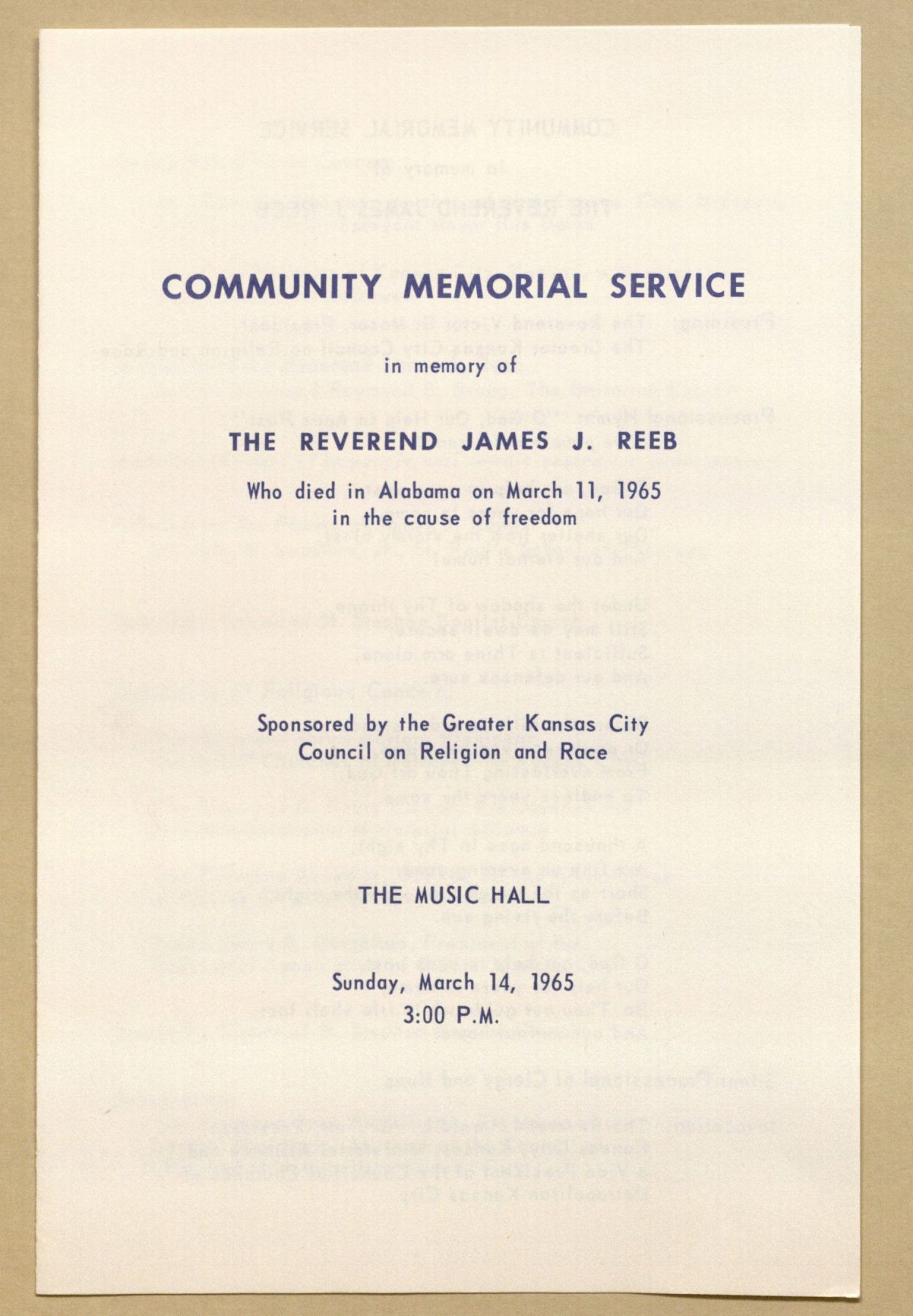

At the Music Hall in Kansas City, Missouri, the Greater Kansas City Council on Religion and Race, an organization of clergy and lay members of all faiths dedicated to the advancement and attainment of interracial justice and charity, sponsored a community memorial service for the Reverend James J. Reeb, who was murdered by white vigilantes in Selma, Alabama on March 11, 1965. He had traveled to Selma a few days after “Bloody Sunday” to support the area’s civil rights workers. A Unitarian Universalist minister and a social worker, The Reverend Reeb was born in Wichita Kansas and resided in Russell, Kansas as a youth.

Reeb Memorial Program. Greater Kansas City Council on Religion and Race Collection.

Call Number: RH MS 786, Box 8, File 12. Click image to enlarge.

The KU Libraries is a co-sponsor of the African and African American Studies Department’s public program Selma: A Film Screening and Panel Discussion on March 25, 2015, at 5:30p.m. in Wescoe Hall, Room 3140.

Deborah Dandridge

Field Archivist and Curator

African American Experience Collections