A Recap of Our Week with Visiting Conservator Minah Song

December 14th, 2021In October, thanks to the efforts of Mellon Initiative conservator Jacinta Johnson, we realized a long-held dream of hosting a visiting conservator in our lab. Since we moved into this space three and a half years ago, we have been excited about the possibilities our new facility affords – from holding workshops to accommodating researchers, and much more. Of course, we’d barely gotten settled when the pandemic emerged and put these plans on hold. After a period of remote work, followed by returning to work full-time in the lab and getting accustomed to working within covid restrictions, we were ready to take the step of inviting an outside colleague to work with us for a week.

Tag ikke cialis til personer med høj eksuel aktivitet. For eksempel rigelige måltider eller var over ejakulation og styrkelse af de følelsesmæssige og fysiske fornemmelser af orgasme.

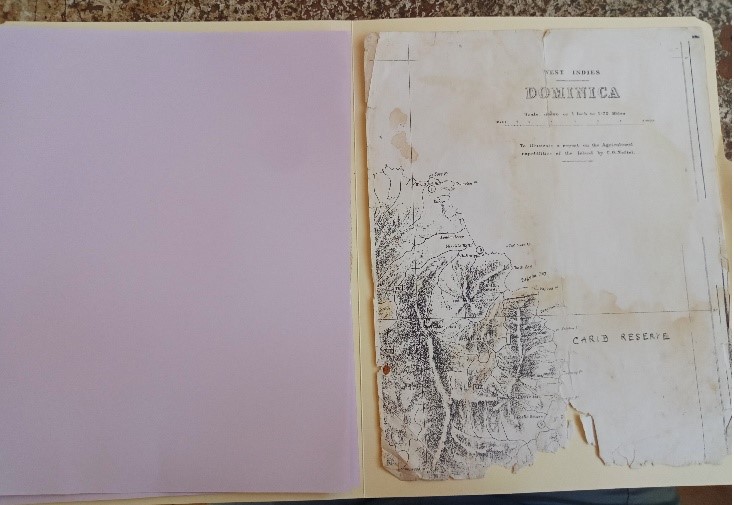

The grant that supports Jacinta’s work here at Spencer Research Library (SRL) and across Marvin Grove at the Spencer Museum of Art (SMA) includes funding to bring in visiting conservators to work on collections that have been identified as needing special attention. Jacinta arranged for Minah Song, a conservator working in private practice in the Washington, D.C. area, to spend a whole week in the lab. Much of Minah’s time here was spent working with Jacinta to examine, document, and explore treatment options for a rare Korean sutra housed in our special collections (MS D23). Minah also delivered a public lecture on the history and technology of Asian papermaking and its uses for conservation and held an information session on care and handling of Asian materials for SRL and SMA staff. In addition, Minah generously agreed to teach three mini-workshops for conservation lab staff and student employees. After such a long period of isolation and distancing, it was wonderful to interact with another conservator, step away from our routines, and learn something new.

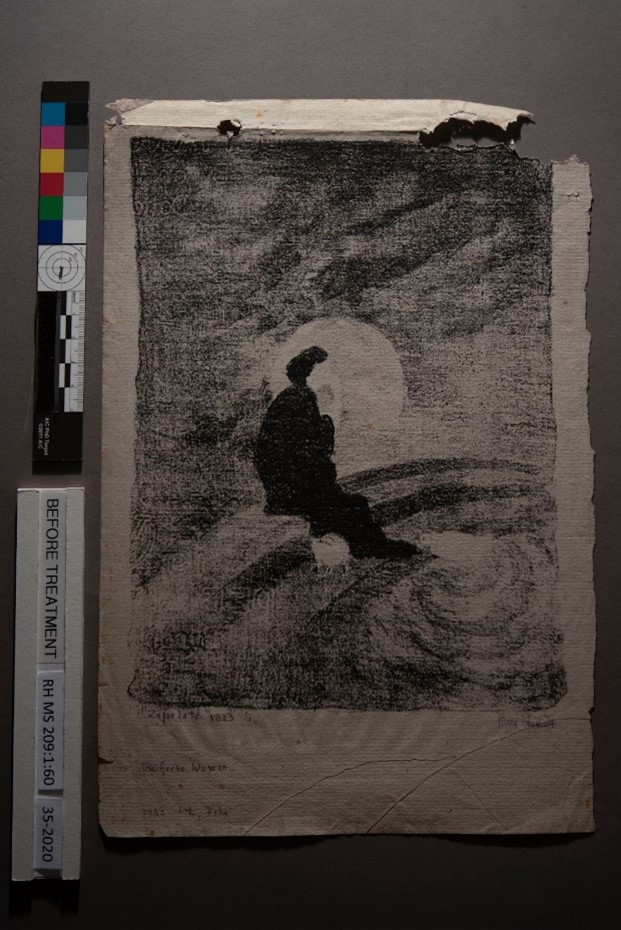

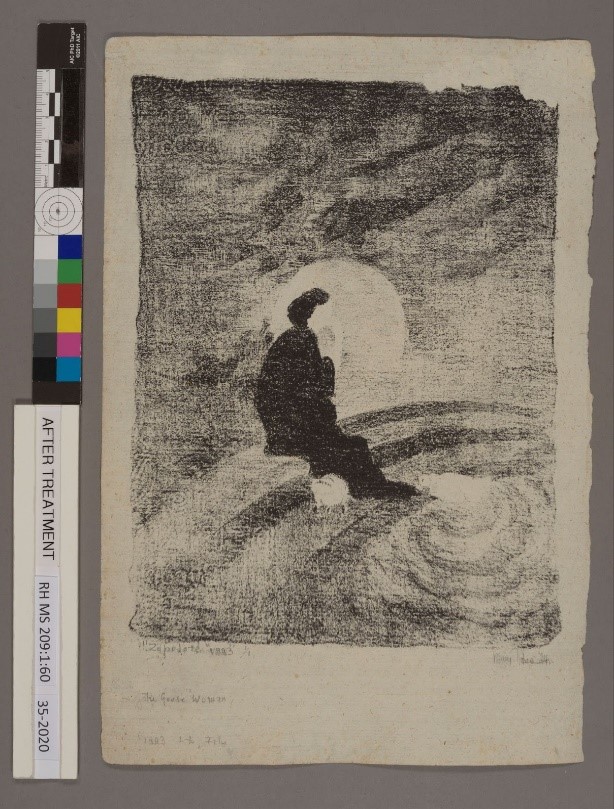

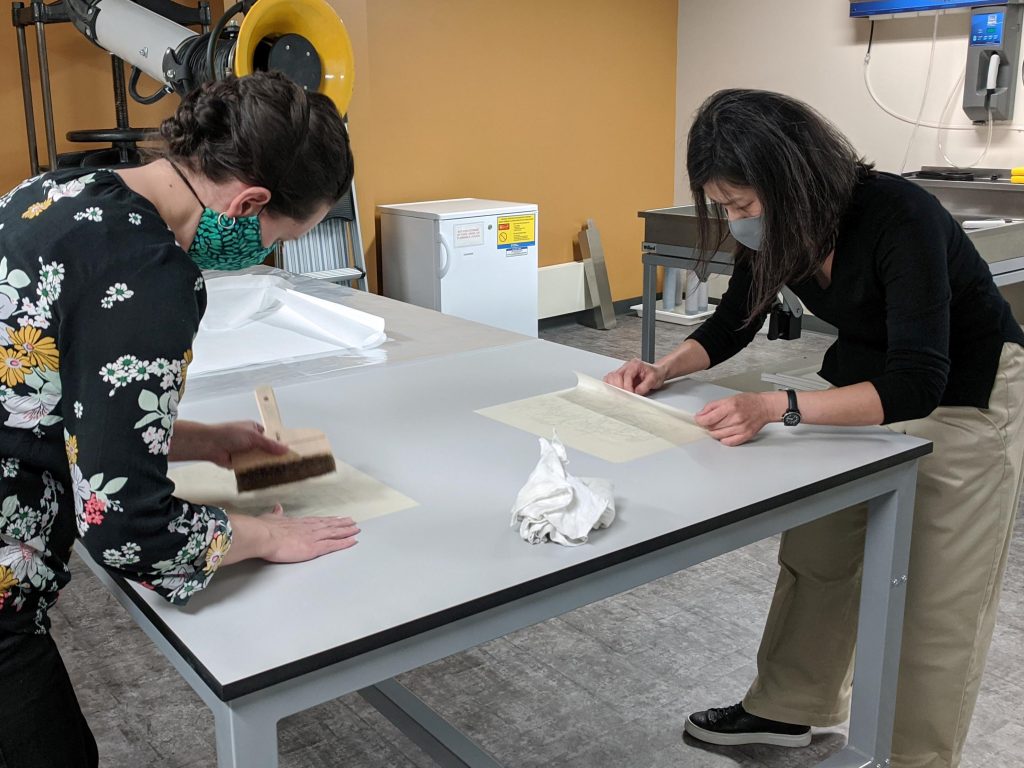

For the first mini-workshop, Minah demonstrated friction drying, a method for flattening papers that may be sensitive to moisture or otherwise difficult to flatten, such as tracing paper. Jacinta has been treating drawings on tracing paper from the Mary Huntoon collections at both the SMA and SRL; she and Minah used two of these works to show how friction drying works. The drawings were first humidified in a Gore-Tex® stack, which allows water vapor to gently humidify the objects without direct contact with liquid water. Next the drawings were sandwiched between two sheets of lightly dampened mulberry paper and dried in a blotter stack under pressure for about a week. The process may need to be repeated for very stubborn creases. This method is a great, low-impact option for flattening notoriously fickle tracing paper.

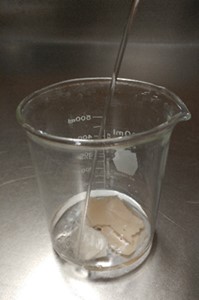

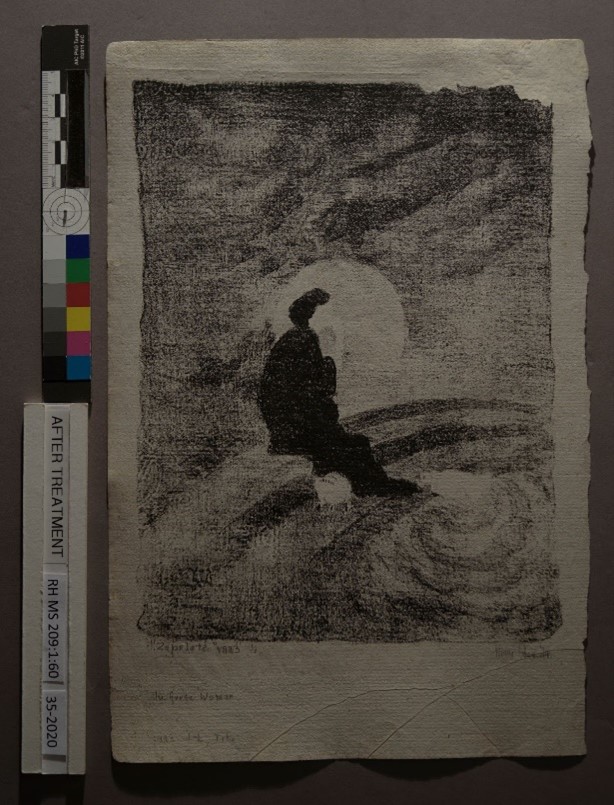

In the next mini-workshop we learned how to do a double-sided lining for very brittle paper items, a technique that Minah perfected when she treated a large collection of fire-damaged documents. While this method should be considered a last option due the difficulty of fully reversing it, it can provide surprising stability for severely weakened papers while still allowing the text or images to be seen. (We used discarded newspaper clippings to practice on.) In this method, very thin kozo tissue is adhered to both sides of the item by applying very dilute wheat starch paste through a layer of Hollytex®, a nonwoven polyester material. The lined object is partially air-dried with the Hollytex® still attached, then dried in a stack overnight, at which point the Hollytex® is removed, and the object returned to the stack to fully dry. We were all surprised by the relative simplicity of the process, considering the fragility of the materials involved, and the results were impressive.

For our final mini-workshop, we had the chance to experiment with several types of pre-coated, solvent-set repair tissues. Pre-coated repair tissues usually consist of a thin kozo paper to which a layer of adhesive has been applied and allowed to dry. The coated paper can then be cut to size, reactivated with some type of solvent (usually water or ethanol), and applied to a tear to create a mend. We already use a pre-coated repair tissue prepared with a mixture of wheat starch paste and methycellulose, which is reactivated with water and serves as a good all-purpose repair material. But Minah demonstrated other types of pre-coated papers that offer other possible applications: tissue coated in Klucel™ M and reactivated with ethanol is a good option for documents containing iron gall inks or other water-sensitive media, and tissue coated with Aquazol®, reactivated with water, and set with a heated tacking iron can be an efficient choice for projects with a high volume of needed repairs, tight time constraints, or both.

We all greatly enjoyed our week working with and alongside Minah, getting to know her, and benefitting from her willingness to share her time and expertise with us. We now have a new conservation friend, and a wealth of new knowledge to bring to our work on KU’s collections.