The Long Haul: Treating One of the Neediest Cases

February 15th, 2016(Part 1 in a series on the treatment of Summerfield D544)

The great majority of the items that we treat here in the conservation lab are in and out of the lab relatively quickly*. (*I use this word in a most qualified and highly subjective way! That usually means anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours to a couple of weeks.) A treatment need not be time-consuming or highly invasive in order to be effective; because there are so very many items in our collections that need treatment, and because we conservators try to take a conservative approach to treatments, we design most treatments to employ our resources – time and materials – as economically as possible while achieving the maximum benefit for the items being treated.

On occasion, however, we encounter items that need extra care and a fuller application of the tools available to us. These treatments are nursed along gradually and in stages, the work carried out alongside and in between shorter-term treatments, and sometimes put away for days or weeks at a time to let more immediate priorities take precedence. I currently have one such treatment on my bench, the Polish printed book, Kazania na niedziele calego roku [i.e., Sermons for Sundays of the Whole Year] by Pawel Kaczyński, published in 1683 (call number: Summerfield D544).

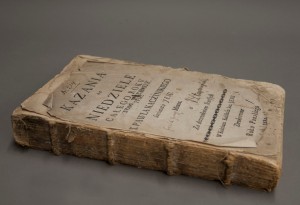

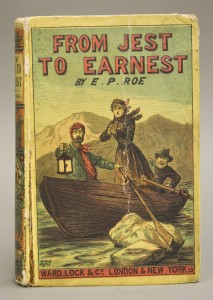

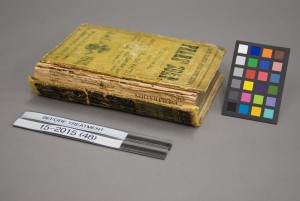

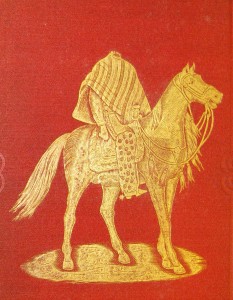

Summerfield D544 before treatment. Special Collections, Spencer Research Library. Click image to enlarge.

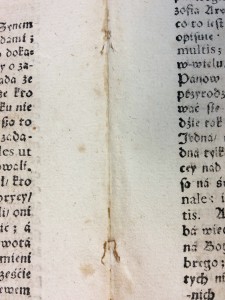

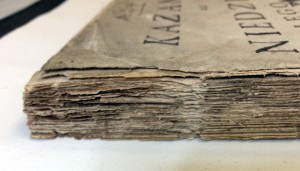

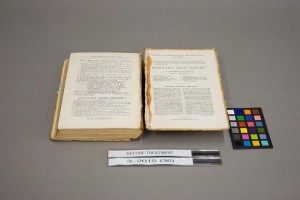

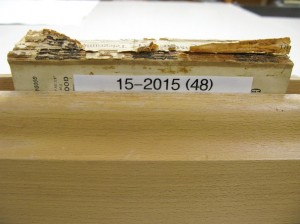

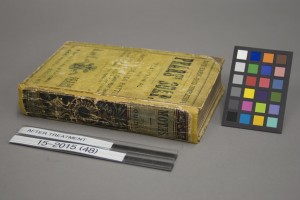

The catalog record notes that Spencer Library’s copy of this title is “imperfect;” indeed, we have only volume 1 of a three-volume set, our volume is missing one page, it has significant losses and edge damage throughout the text block, and not least of all, it is missing its binding. What remains of the volume is dirty and worn, and its sewing is rather carelessly executed, which limits the volume’s opening and has resulted in damage along the spine where sloppily-inserted thread has torn through the paper. In addition, the spine is coated with a thick waxy substance that is causing discoloration and breakage along the spine folds.

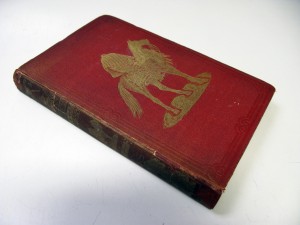

Example of damage caused by poor sewing. Click image to enlarge.

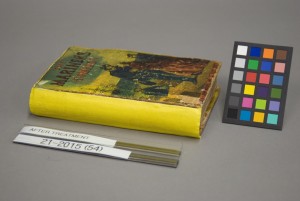

Damage caused by waxy spine coating. Click image to enlarge.

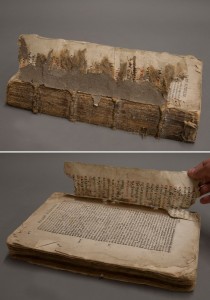

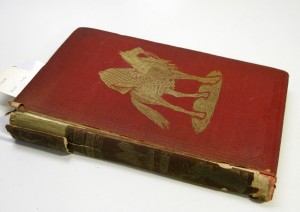

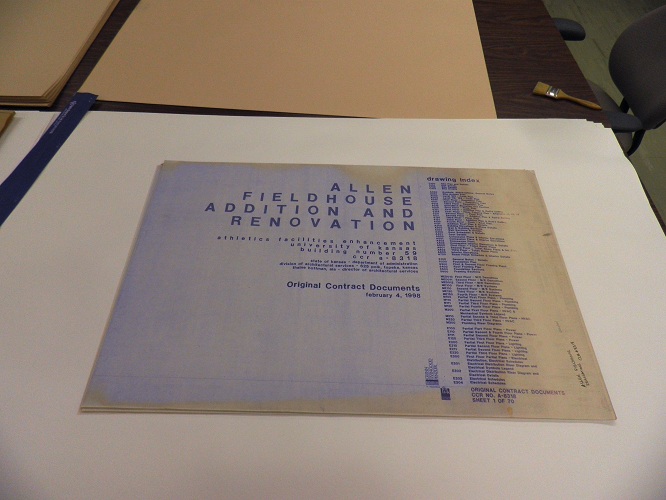

This poor volume had been housed in a simple envelope, and was at the very least in need of better housing, but one interesting feature drew our attention: a fragment of manuscript binder’s waste still adhered to the frayed cords on the back of the volume. It is not unusual to see repurposed manuscripts in books from this time, and the Summerfield Collection has many other examples of binder’s waste in its books. The fragment on Kazania is a bit different, however, because the language in which it is written appears to be Old Church Slavonic (while most of the manuscript fragments we see tend to be in Latin) and because the material it is written on is paper, rather than parchment.

Manuscript binder’s waste on the back of the volume. Click image to enlarge.

The fragment was dirty, torn, and completely obscured on one side by the pasted-down cords and layers of delaminated board from the missing binding. Normally we would attempt to preserve binder’s waste on the volume itself, but in this case, absent a binding and with the fragment at risk for further damage, we consulted with the collection curator and opted to release the fragment from the cords, clean it to the extent possible in order to reveal the concealed manuscript, and house it with the volume, including photographs of its original condition, as a teaching tool.

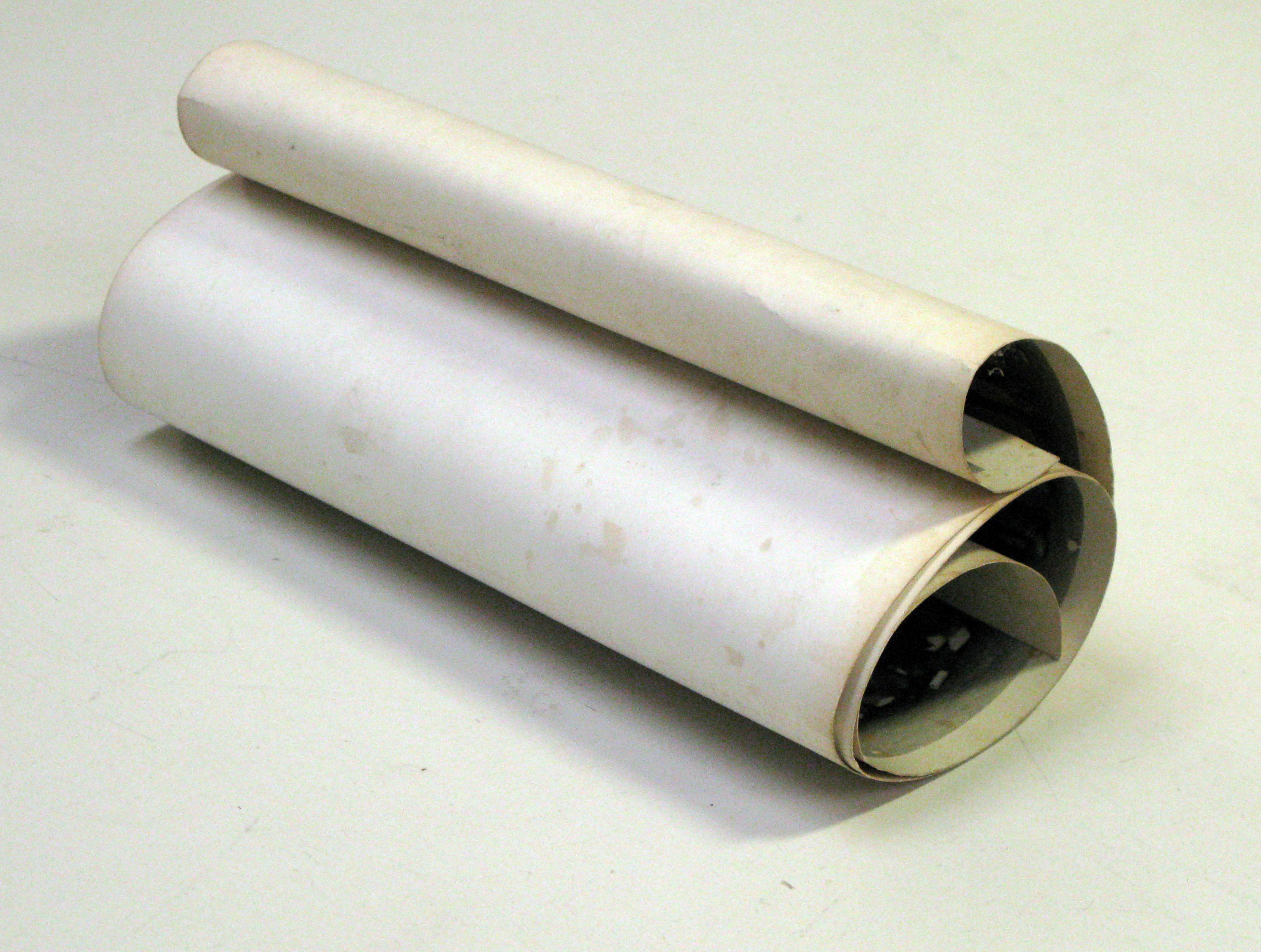

But what about the rest of the volume? In its present condition it is not suitable for use, and its sewing is causing damage to the text block, so we decided that the volume should be disbound, cleaned, mended, sewn up again, and placed into a limp paper conservation case binding. A paper case, similar to the one shown here at left, has many benefits: it will protect the text block and allow for safer and easier handling of the volume; it can be easily removed from the volume if its conservation or binding needs ever change in the future; and it will have an aesthetically appealing appearance that will integrate well on the shelf with other volumes in the collection.

This treatment, then, is one of those exceptions to our generally conservative practice – some items just need more help than others. Now that you’ve been introduced to this volume in its before-treatment condition, stay tuned to this blog for updates as the treatment progresses. The next installment in this series will cover the removal of the manuscript fragment, dismantling of the sewing, and the cleaning and preparation of the text block for re-sewing.

Angela Andres

Special Collections Conservator

Conservation Services