New Finding Aids, January-June 2022

July 19th, 2022Supply chain issues and lower staffing levels have continued to affect our ability to process new collections in the first half of 2022, but despite this we have continued to process and describe new materials. We’ve also been able to return to a project that has long languished, in which we are inventorying and describing the official records of the University of Kansas, including creating finding aids for record groups that were previously undescribed in an easily accessible, online way. Look for updates to our record group listings throughout the rest of this year and beyond!

You’ll see some newly described record groups in the list below, amongst our other newly processed collections.

William Coker collection, 1932-2004 (RH MS 1550)

Hodgeman colony history collection, 1879-1963 (RH MS P977)

Chester Owens collection, 1923-2010 (bulk 1950s-1980s) (RH MS 1549, RH MS R496)

Paul A. Black photograph album, approximately 1916-1938 (RH PH 564)

Philippine-American War diary by a U.S. officer, March 25-April 6, 1900 (RH MS C93)

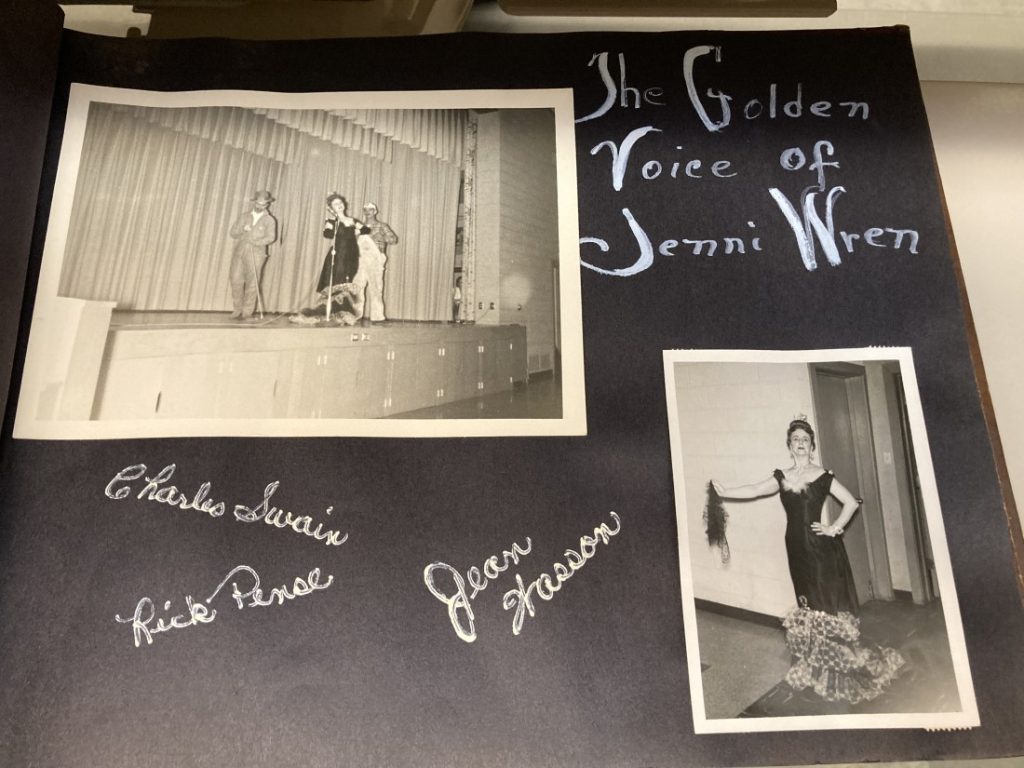

Dotti McClenaghan “Follies” collection, 1959, 1963 (bulk 1959) (RH PH 563)

Pace and Mendenhall family photographs, 1909, 1925-1935, undated (RH PH 562)

Jerauld R. Crowell papers, 1963-2018 (RH MS 1551, RH MS R497, RH MS R498, RH MS S76, KC AV 115)

Independent Order of Good Templars of Jefferson County, Kansas, Lodge No. 17 records, 1874, 1876 (RH MS P978)

June flood of 1908 at Kansas City postcards, June 1908 (RH PH P2843)

Walter Thomas Bezzi journals, 1975-1985 (RH MS 1552)

Bullene family bible, [bible printed in 1833, includes information dating up to 1926] (RH MS 1546)

J.C. Nichols Investment Company covenant book, November 1922 (RH MS P976)

Bell Memorial Hospital photograph, 1918 (RH PH P2842(f))

Clarence Kivett papers, 1977-1995 (RH MS 1547)

Harris family papers, 1965-2019 (RH MS 1543, RH MS Q483)

Perry Alan Werner photograph collection, December 1977-September 1978 and undated (RH PH 561)

1890s family photograph album, probably from Kansas, 1890s (RH PH P2845)

James Milton Turner correspondence, July 1884 (RH MS P979)

Langston Hughes play scripts, 1937-1958 (RH MS 1554)

Robert C. Wilson collection, 1967-1999 (RH MS 1556, RH MS R501, KC AV 119)

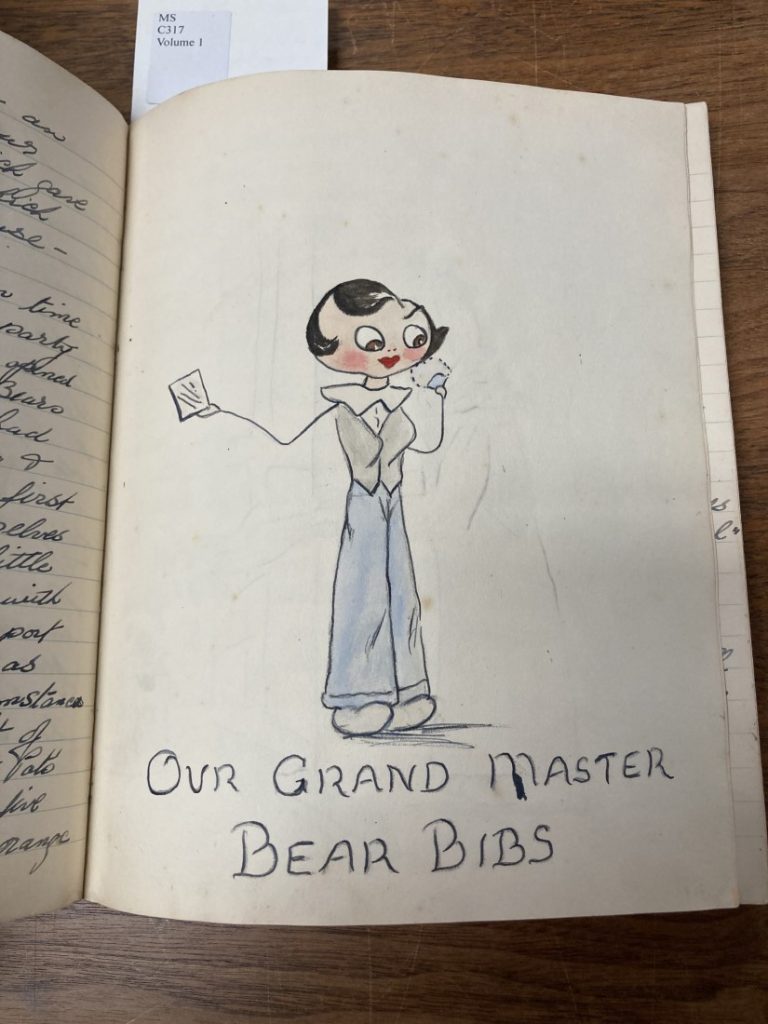

“The Order of the Little Bears” notebook, April 7, 1942-May 1943 (MS C317, MS P761)

Personal papers of Thomas N. Taylor, 1961-2016 (PP 631)

Hinton family papers, 1921-2016 (RH MS 1558, RH MS Q489, KC AV 120)

“These Were People of Mercy” Stoner family genealogy, December 2019 (RH MS D302)

John Parks enlistment papers, October 1, 1863 (RH MS P980)

Joshua William Beede letters, April 6, 1899 and August [1899?] (RH MS P981)

Postcards addressed to Lillian Mitchner, 1910 (RH MS P982)

Records regarding Faculty and Staff at the University of Kansas, 1880s-2020 (bulk 1930s-2000s) (RG 41)

Records of Radio, TV, and Film at the University of Kansas, 1923-2019 (bulk 1950s-1980s) (RG 40)

Records of the Office of Public Safety at the University of Kansas, 1925-2019 (RG 48)

Personal papers of Neil J. Salkind, 1970-2017 (PP 632)

Personal papers of Anton Rosenthal, 1984-2020 (PP 633)

Personal papers of Larry Martin, approximately 1972-2010 (PP 630)

Living the Dream, Inc. invitation, 2020 (RH MS P988)

Margaret Kramar collection, March 2017 (RH MS P987)

John Swift school records, 1950-1956 (RH MS P986)

Amelia Pardee Ellis McQueen collection, 1862-1997 (RH MS P985)

Blue Rapids Supply Company brochures, February 1940, September 1941 (RH MS P984)

“Grandmother’s Letters,” by Louisa B. Simpson, 1847-1864 (RH MS P983)

U.S. Committee on Public Information Division of Women’s War Work collection, December 1917-July 1918 (MS 371, MS Qa40)

Personal papers of Donald Stull, 1967-2015 (PP 583)

Personal papers of Charles D. Bunker, 1901-1937 (PP 634)

Marcella Huggard

Manuscripts Processing Coordinator