That’s Distinctive!: Dinosaur

March 3rd, 2023Check the blog each Friday for a new “That’s Distinctive!” post. I created the series because I genuinely believe there is something in our collections for everyone, whether you’re writing a paper or just want to have a look. “That’s Distinctive!” will provide a more lighthearted glimpse into the diverse and unique materials at Spencer – including items that many people may not realize the library holds. If you have suggested topics for a future item feature or questions about the collections, feel free to leave a comment at the bottom of this page.

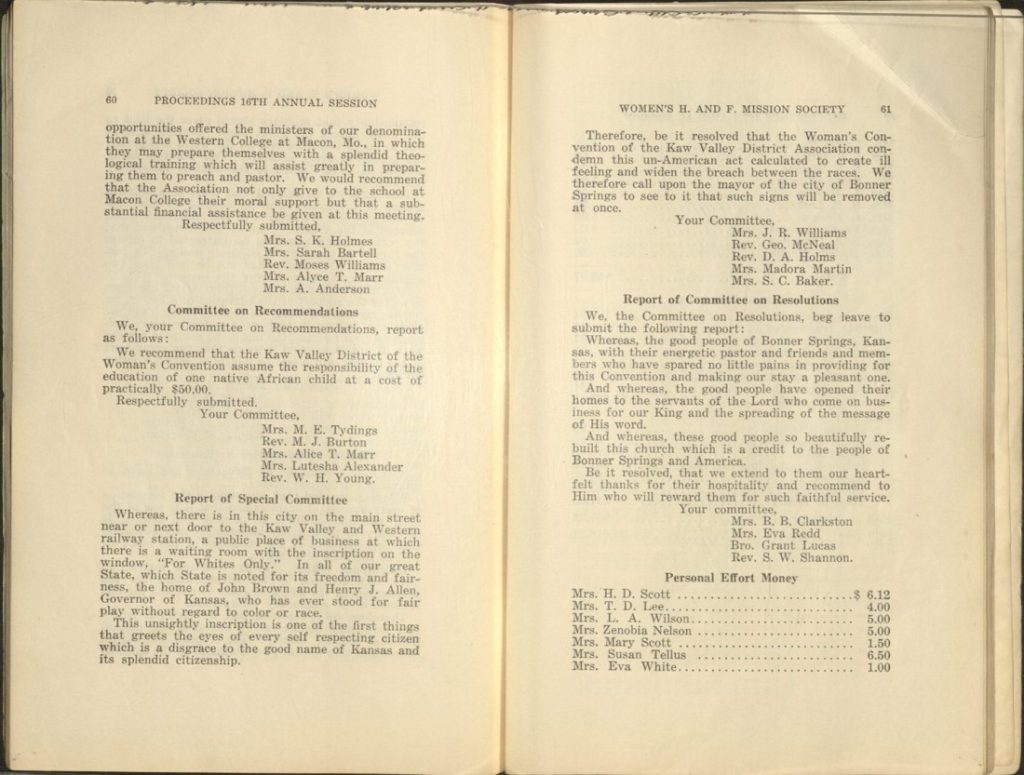

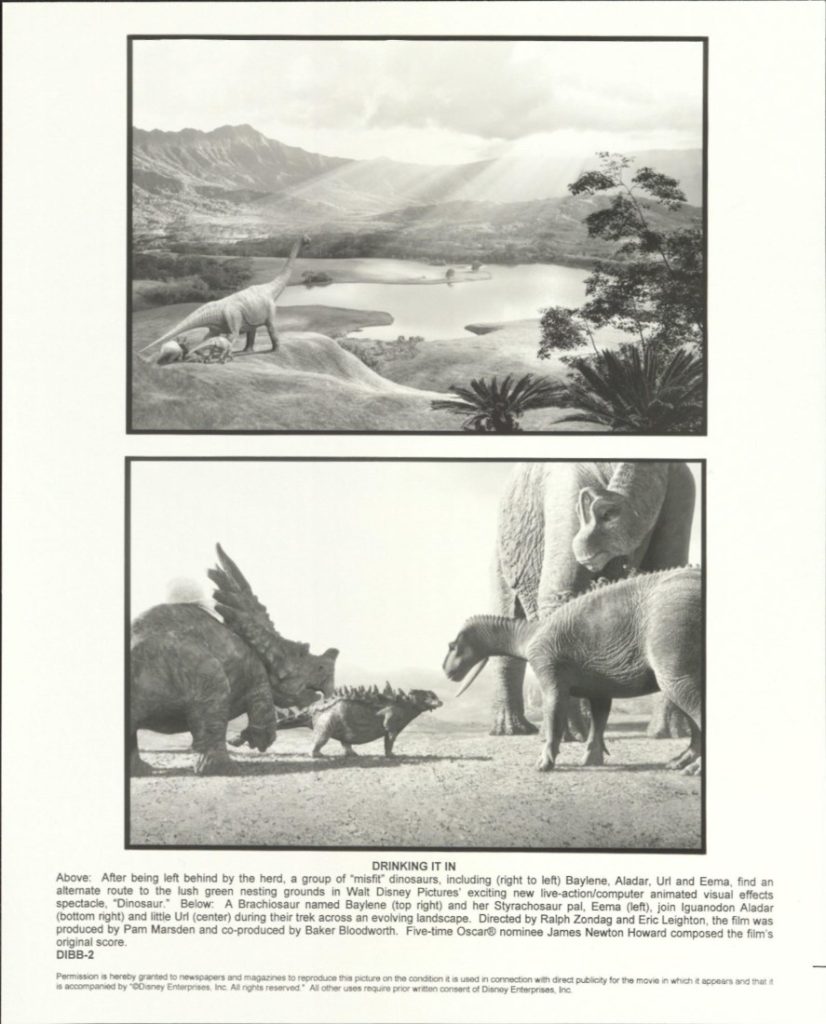

This week on That’s Distinctive! we are highlighting some animation stills from the John C. Tibbetts collection housed here at the library. The collection – which spans 18 boxes and two oversize folders – contains Hollywood press kits from various movies released between 1978 and 2004. The kits generally consist of production information, biographical information on the actors, story information, and press release information. Most kits contain some form of visual materials, such as stills, slides, or digital press kits; the digital files are on CD-ROM and contain a variety of items including images, video clips, and production information. The collection includes movies like Back to the Future, A Bug’s Life, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, and Jeepers Creepers.

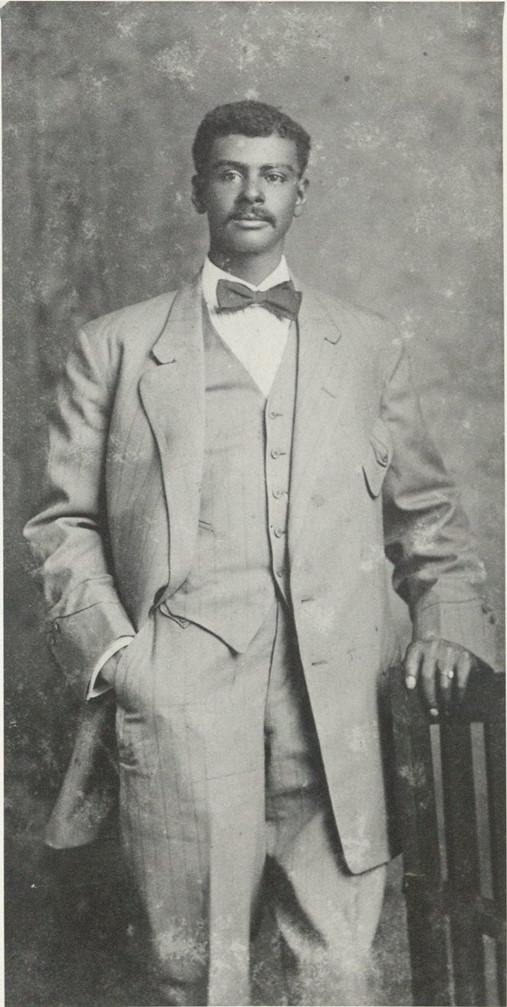

Dr. Tibbets, a now retired professor with KU’s Department of Film and Media Studies, donated the collection to Spencer in 2010. Tibbetts worked as a full-time broadcaster from 1980 to 1996. He hosted his own television show in Kansas City, Missouri, and worked as an Arts and Entertainment Editor and Producer for a variety of radio and television outlets, including KCTV (Kansas City’s CBS affiliate), KMBC Radio, and KXTR-FM Radio. During that time, he also contributed many broadcast stories about musicians, painters, writers, and filmmakers to CBS Television, the Christian Science Monitor Radio Network, Voice of America, and National Public Radio. He has produced two radio series about music, The World of Robert Schumann and Piano Portraits.

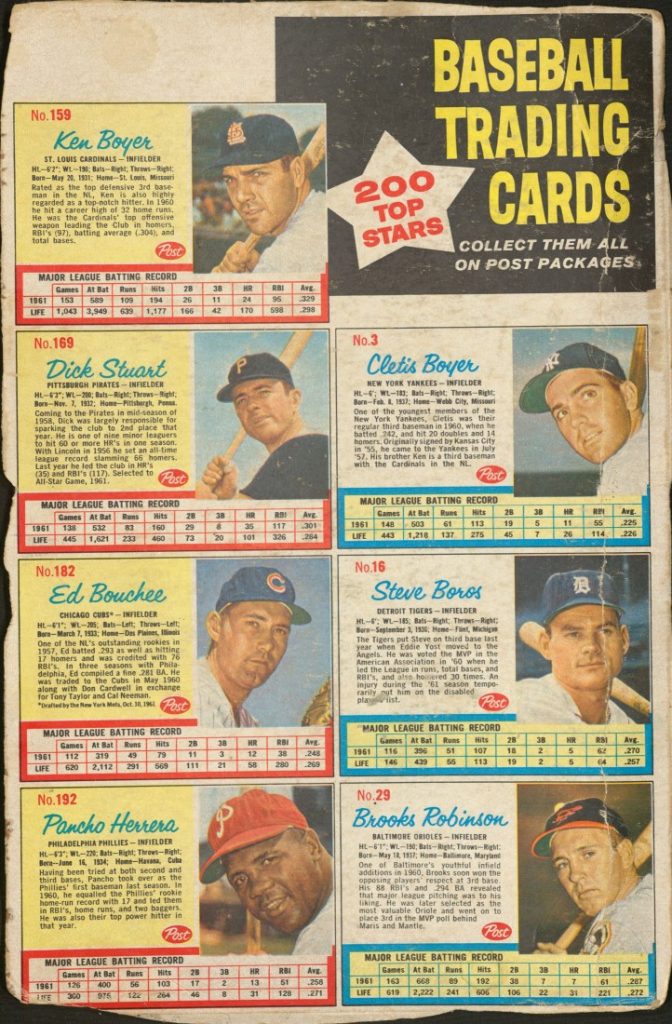

While there are a wide range of films in the collection, this week we are sharing stills from the 2000 animated movie Dinosaur. The movie, which was released May 19, 2000, follows Aladar, an iguanodon, and his family of prehistoric lemurs as they join a herd of dinosaurs heading to the safety of the nesting grounds after a meteor strike. The movie portrays the hardship and happiness that comes along through Aladar’s life and teaches that perseverance can go a long way. The collection includes both stills and a press kit with production notes on the film.

The John C. Tibbetts collection, along with all items in the library, can be viewed in the Reading Room from 10am to 4pm Monday through Friday. The library is open to the public and welcomes researchers of all types.

Tiffany McIntosh

Public Services