Researchers Wanted!

June 6th, 2014Ask any special collections librarian or archivist about her favorite collection item, and she may hem and haw (how can you pick just one favorite?!?). However, ask that same librarian about interesting items or collections that she wishes more researchers would use, and invariably she will rattle off a frighteningly long list.

This week, in the spirit of summer discovery, we present two intriguing selections that scream “researchers wanted!”

1. Papers of William Poel, ca. 1895-1934 (MS 31)

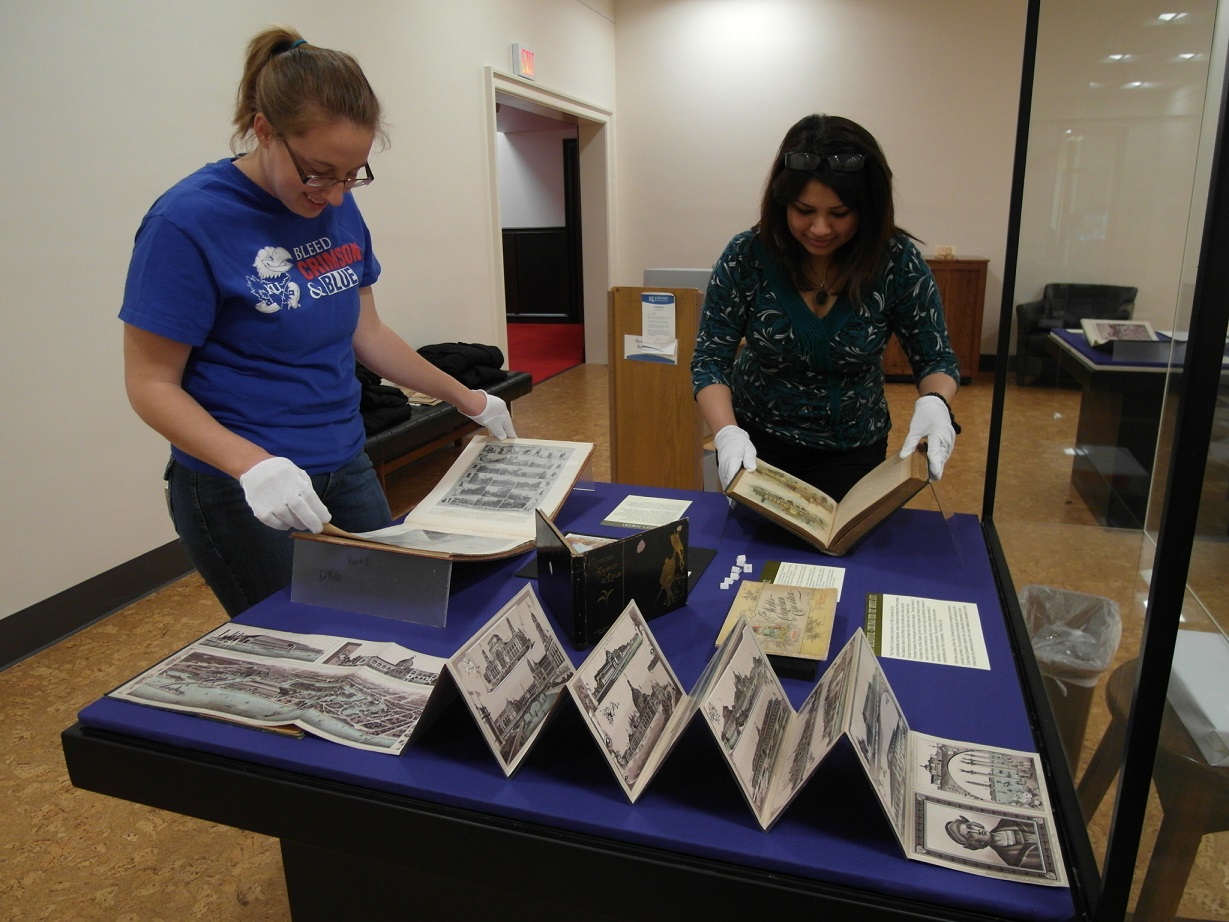

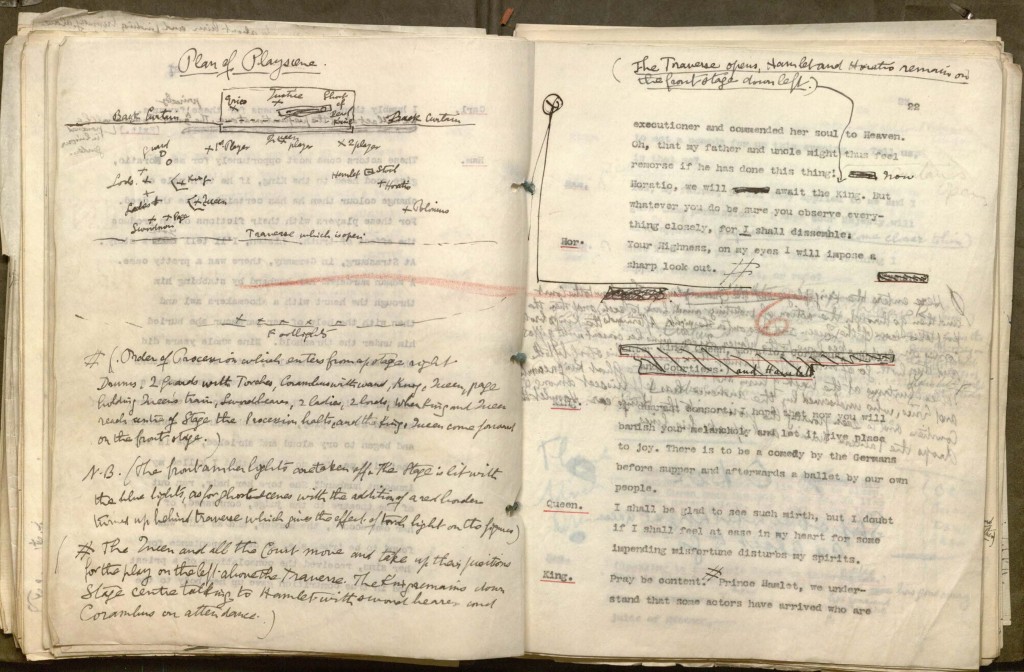

As admirers of William Shakespeare know, this April marked the 450th anniversary of the playwright’s birth. And while Spencer doesn’t have a manuscript by the Bard gathering dust on a shelf (no manuscripts in his hand are known to survive), the library does hold papers for William Poel (1852-1934), an actor, writer, and theater director known for his attempts to revive the conventions of the Elizabethan stage at the dawn of the twentieth century. The collection includes correspondence with figures from the theater world (actors, writers, critics, and others), a small number of scripts, prompt books, and journals, and ephemera such as playbills and review clippings. Pictured below is Poel’s heavily annotated prompt copy for Fratricide Punished, a German version of Hamlet of ambiguous relation to Shakespeare’s play. Also pictured are a theater program and a lecture announcement, examples of Poel ephemera.

Top: Poel’s prompt book for Fratricide Punished , ca. 1924. MS 31:D4; Bottom: an announcement for a series of lectures by Poel on Shakespeare, 1900, and the program for a production of Marlowe’s Faustus directed by Poel, 1904. MS 31, F6. Click images to enlarge.

2. Don Quixote, el Castellano viejo, undated (before 1860).

This mysterious bound manuscript came to Spencer from the library of the well-known nineteenth-century art historian, bibliophile, and Hispanist, Sir William Stirling Maxwell (1818-1878). A portion of Stirling Maxwell’s vast library was sold at auction and 1958, enabling KU to acquire a significant number of early printed Spanish volumes, including important editions that now form the basis of Spencer’s Cervantes Collection, and this manuscript. As far as we know, the author of this manuscript has not been identified, though the text concerns Cervantes’s famed character Don Quixote. A note pasted toward the front gives further provenance, describing it as a “curious manuscript” sold as part of the auction of the library of “the late Don Justo de Sancha” by Sotheby’s in December of 1860. Though the hand is later than Cervantes’s time, scholars of Spanish literature might find much to pique their interest in this 205-page manuscript. The pictures below include the table of contents, which offers readers an idea of the matter covered.

Don Quixote, el Castellano viejo, undated (before 1860). MS C73. Click images to enlarge.

For more information on these and any of our other manuscript holdings, please don’t hesitate to contact us. After all, the summer is an ideal time to start a new research project.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian