Creating Authority: Printing with Anglo-Saxon Type

July 17th, 2014This week’s post comes from Amanda Luke, a recent KU graduate and a Reference Specialist at Watson Library. Amanda is currently working toward her Master of Library Science (MLS) degree at Emporia State University.

There is a special connection between Anglo-Saxon typeface and the religious controversy that defined late sixteenth-century England. With the Church of England only decades old and tensions between Catholics and Protestants higher than ever, church officials sought to establish ties between the new Church and earlier English history. One connection manifested itself through church manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Some of these religious texts appeared in Old English, the “vulgar” or common tongue of the Anglo-Saxons, who occupied England before the Norman conquests in the eleventh century. Matthew Parker (1504-1575), Archbishop of Canterbury, was the one of the earliest proponents of Anglo-Saxon scholarship. Parker hoped that having these Anglo-Saxon manuscripts translated and printed would lend legitimacy to the new Church through ties to early English religious doctrine.

Parker’s chief interest lay in a series of Latin and Old English texts by Ælfric, an abbot who lived circa 950 – 1010. Copies of these documents had been found at the Worcester and Canterbury cathedrals (Evenden 81). These texts, which Parker’s secretary John Joscelyn likely translated, touched on the subject of the Eucharist and seemed to challenge the Catholic belief in transubstantiation, or the literal transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ (Evenden 81). This rejection of Catholic doctrine was vital for Parker because it provided evidence that the current Catholic thinking was not always present in England.

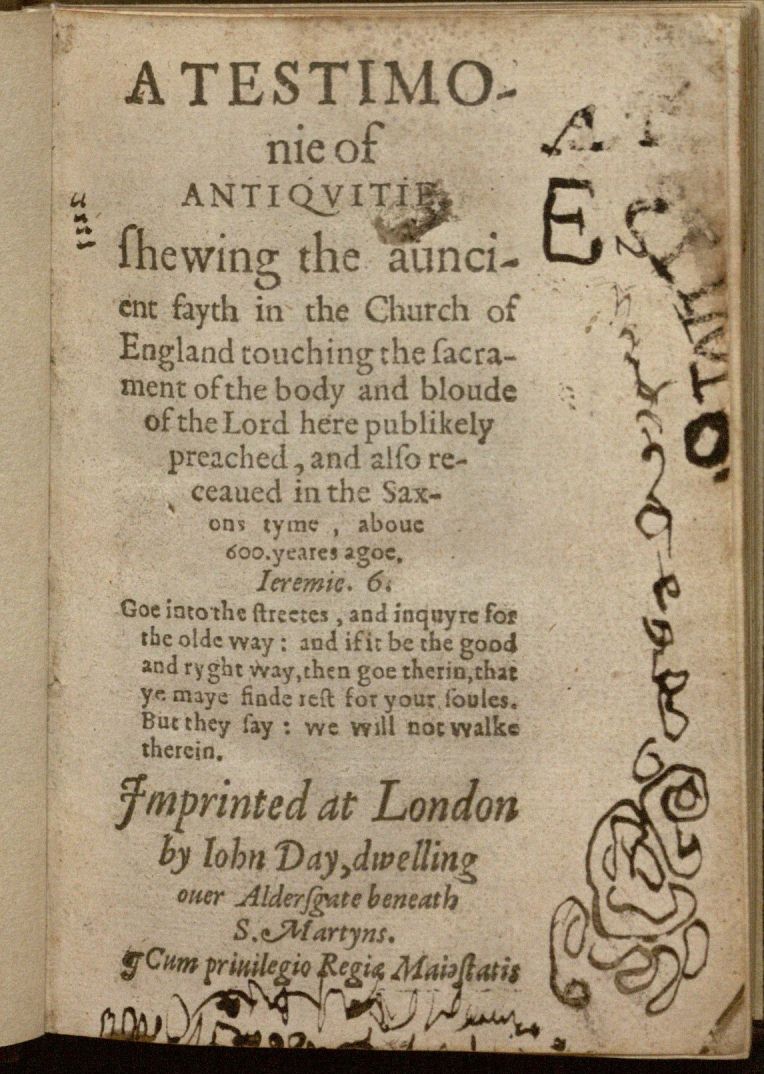

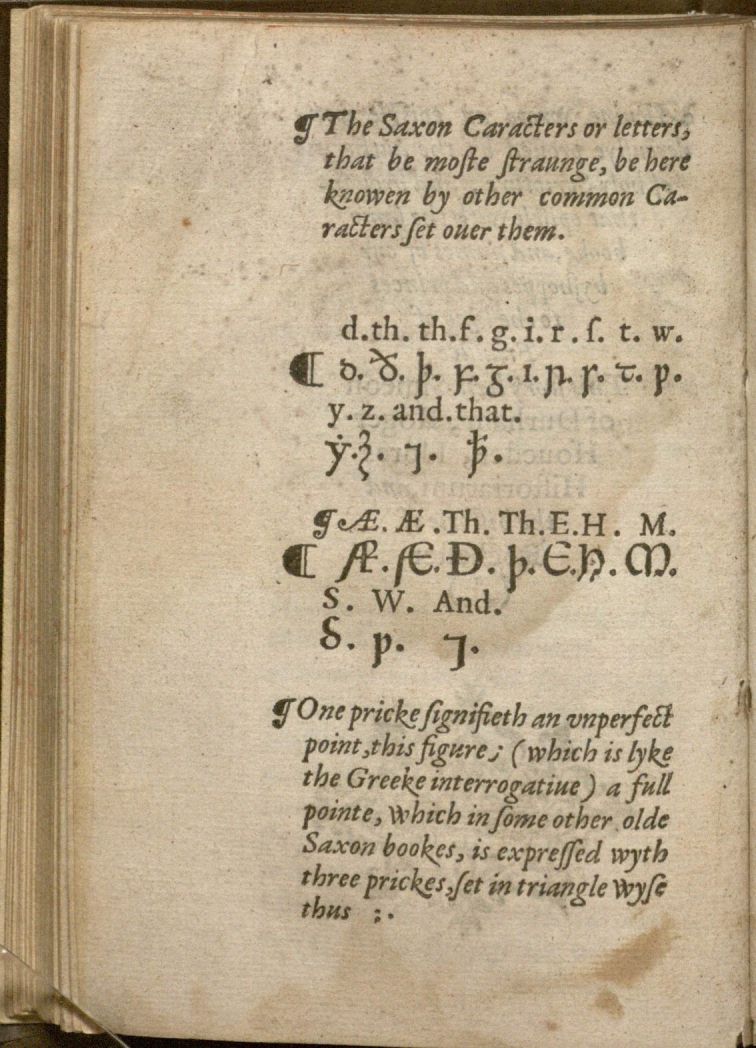

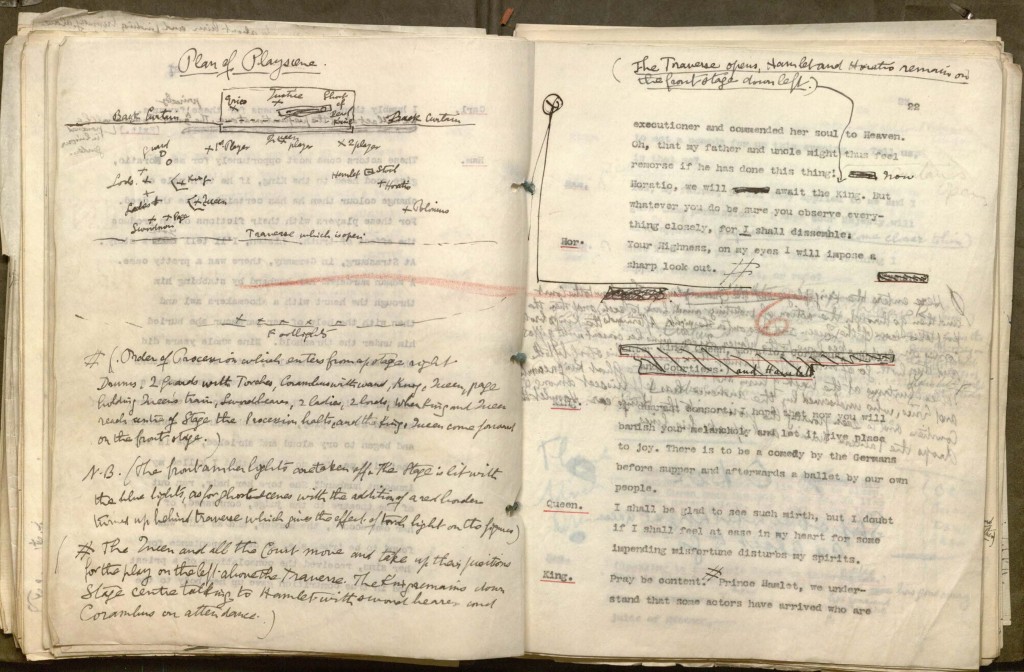

Left: Title page; Right: Old English characters explained. From: Aelfric, Abbot of Eynsham. A Testimonie of Antiquitie

ſhewing the auncient fayth in the Church of England touching the ſacrament of the body and bloude of the Lord […].

London: Iohn Day, [1566?]. Call Number: Clubb A1566.1 Click images to enlarge.

To disseminate this claim he employed a London-based Protestant printer named John Day for an unprecedented task: the development of a typeface which included all of the special characters present in the Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. The development of this Anglo-Saxon type, often just called Saxon type, was an enormous financial risk for Parker. It was estimated by modern scholar Peter Lucas that the typeface would have cost the vast sum of £200 to create (Evenden 82). The typeface which Day cast was 16 point, or slightly smaller than a great primer, a 17 point type (Clement 209). It contained fourteen lower and ten upper case Old English characters not found in the Latin alphabet (see above). It is fascinating to note the several forms of the diphthong “th” in the alphabet (eth ð and thorn þ), as well as the presence of a symbol for the word “and.”

The earliest book containing the Anglo-Saxon typeface was printed by John Day in 1566 at Parker’s request. The volume was titled A Testimonie of Antiquitie ſhewing the auncient fayth in the Church of England touching the ſacrament of the body and bloude of the Lord here publikely preached, and alſo receaued in the Saxons tyme, aboue 600. yeares agoe, and was attributed to Ælfric, the author of the text that influenced Parker. As its long title suggests, this text is a translation of an Easter sermon which touches on the communion. It was especially important to Parker because it supported his mission to legitimize the doctrines of the Church of England. The creation of the Saxon typeface to accompany the translation was, according to scholar Richard Clement, a means of further legitimizing obscure texts. He writes, “Parker’s men began to examine the manuscripts and were impressed by the visual impact of the Anglo-Saxon texts which almost jumped off the page and proclaimed their antiquity and authority to the reader” (Clement 206). Use of the Saxon typeface also helped to differentiate the Old English text from the Latin and English used in the book.

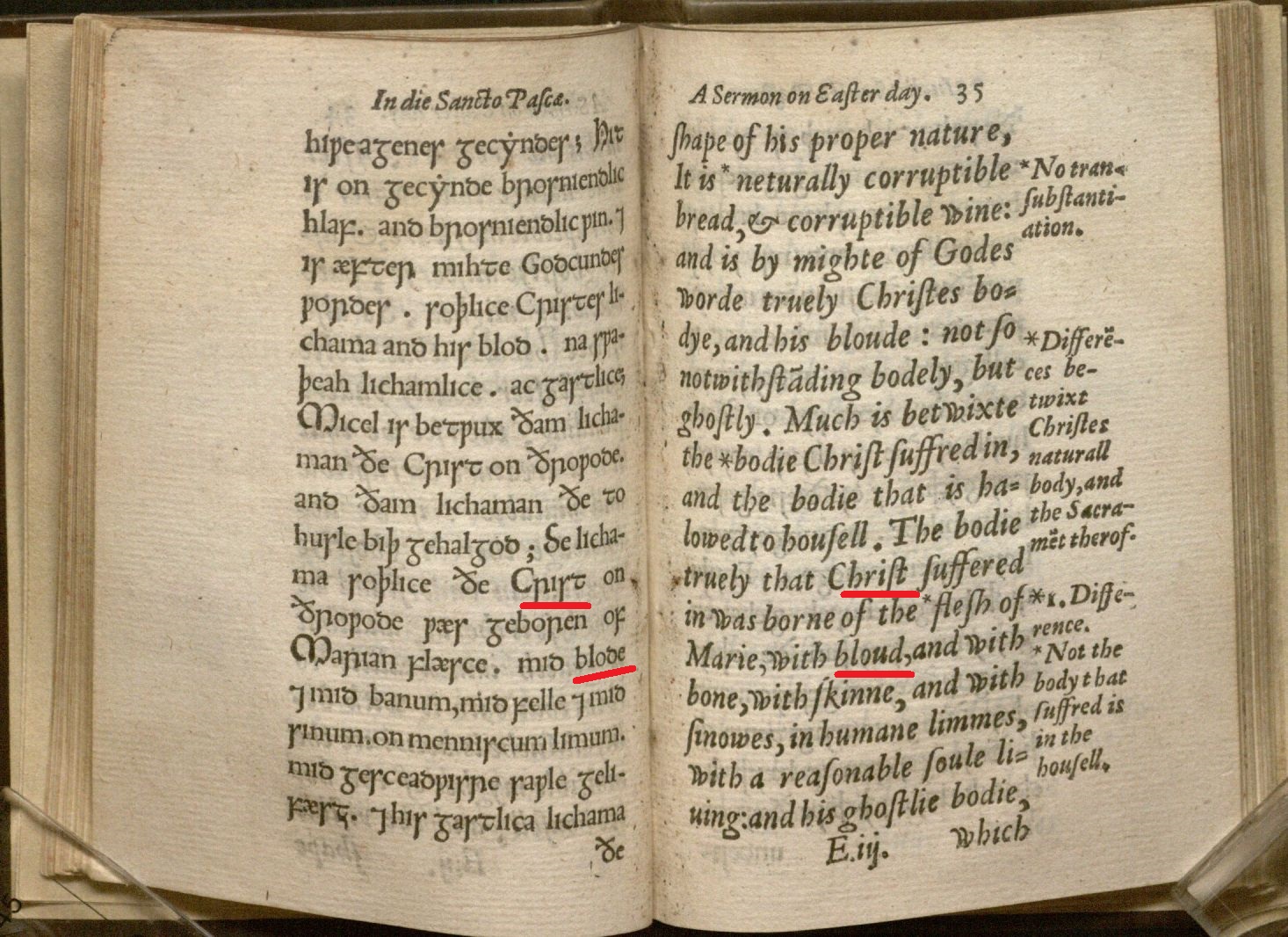

Passage on the transubstantiation (with red underlinings added). Aelfric, Abbot of Eynsham. A Testimonie of Antiquitie …].

London: Iohn Day, [1566?]. Call Number: Clubb A1566.1 Click image to enlarge.

In the image above, the volume is opened to folio 35, which contains a central moment in the Easter sermon. A printed note in the margin reads “No transubstantiation,” highlighting one of the major doctrinal connections Parker was trying to make between the historical church and the Church of England. The text in Saxon type appears on the left, and the translation appears on the right. Even if you cannot read Old English, words such as “blode” and “Christ” can be made out (see the words underlined in red). Thus the facing page format supported the preface’s claim that everything in the translation was true and accurate.

The use of the Saxon typeface in A Testimonie of Antiquitie opened the door for the expansion of Anglo-Saxon scholarship. To explore the subject further, visit Spencer and use its Clubb Collection of Books Printed with Anglo-Saxon Type.

Amanda Luke

KU Alumna and Reference Specialist, Watson Library

Works Cited

Clement, Richard W. “The Beginnings of Printing in Anglo-Saxon, 1565-1630.” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America.91.2 (1997): 192-244. Print.

Evenden, Elizabeth. Patents, Pictures, and Patronage: John Day and the Tudor Book Trade. Burlington: Ashgate, 2008. Print.

![Saint John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople. [Extracts from the works, In Russian]. Manuscript from Russia, 16th-17th century. Call number MS C38. Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas.](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/MS-C38-208x300.jpg)