In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

Click images to enlarge.

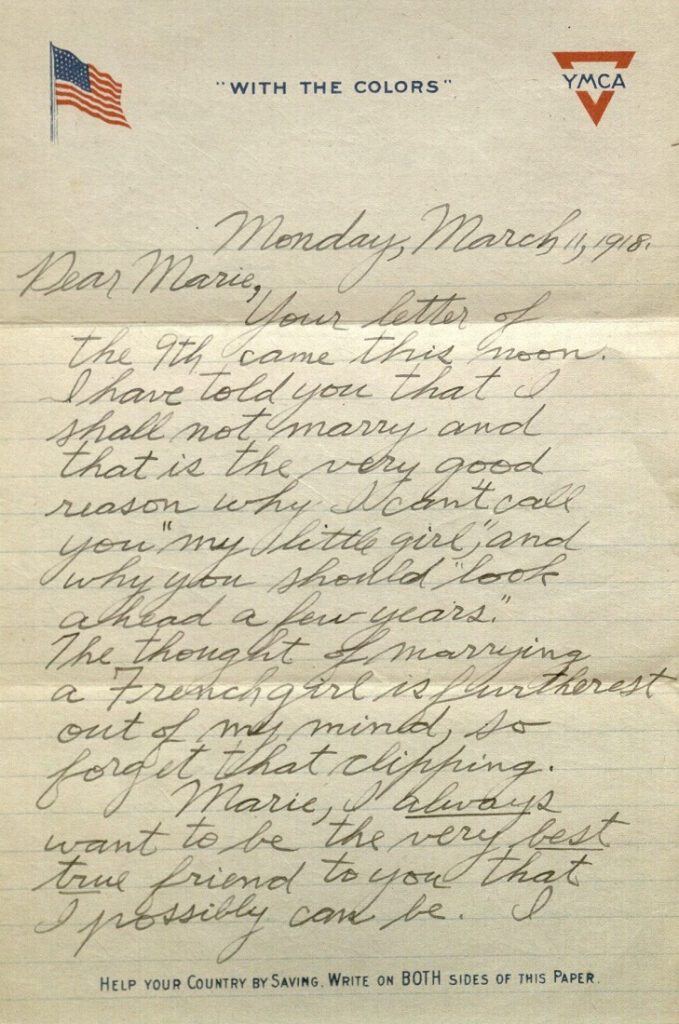

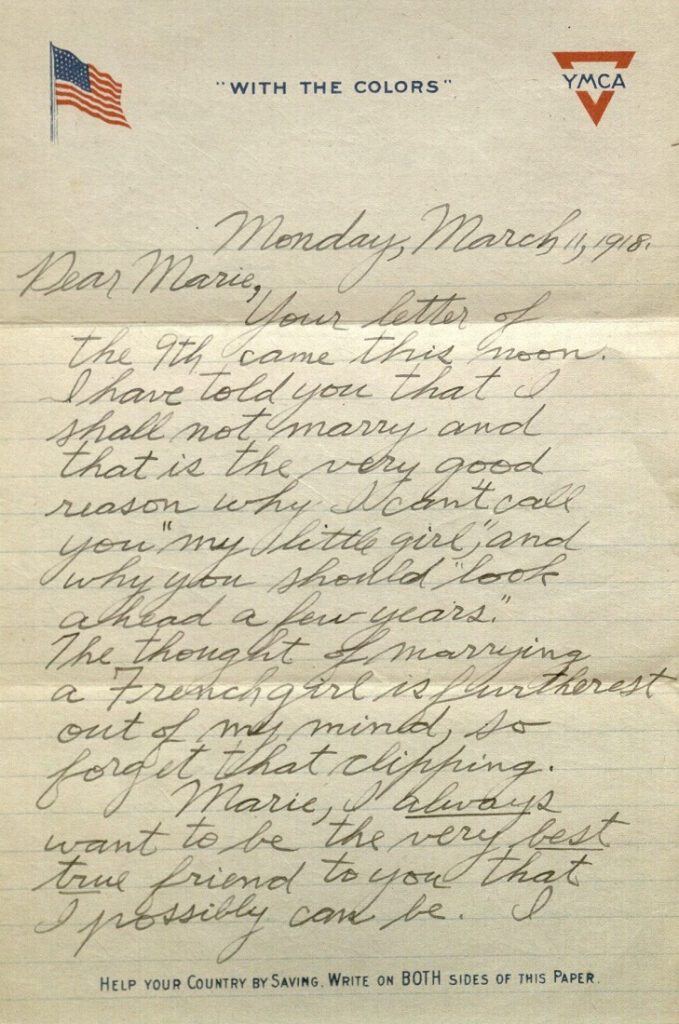

Monday, March 11, 1918.

Dear Marie,

Your letter of the 9th came this noon. I have told you that I shall not marry and that is the very good reason why I can’t call you “my little girl,” and why you should “look ahead a few years.” The thought of marrying a French girl is furtherest out of my mind, so forget that clipping.

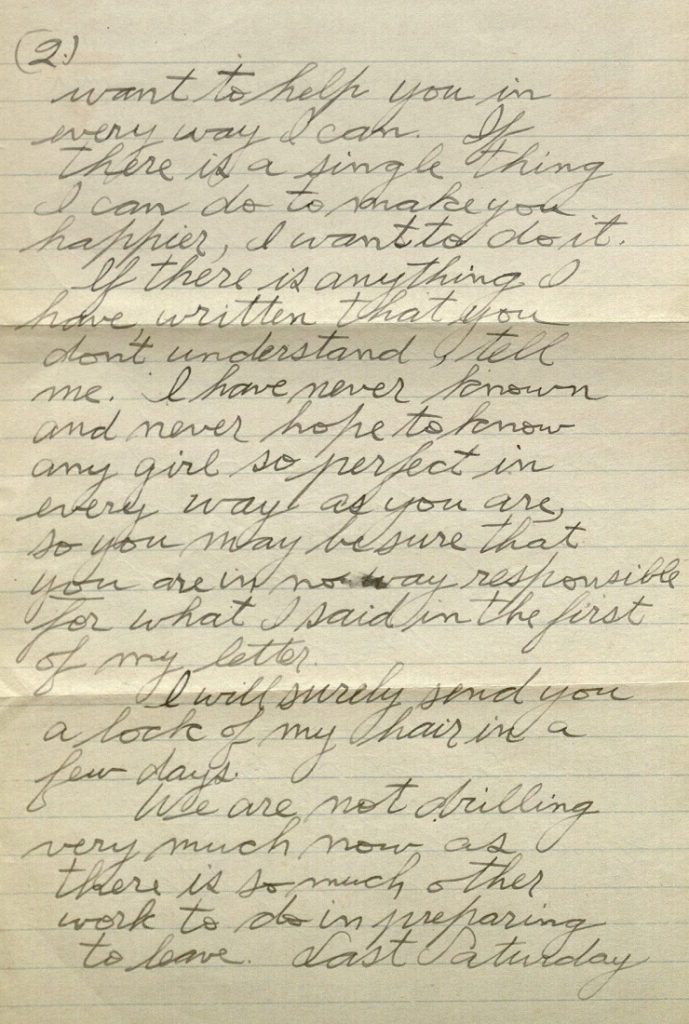

Marie, I always want to be the very best true friend to you that I possibly can be. I want to help you in every way I can. If there is a single thing I can do to make you happier, I want to do it. If there is anything I have written that you don’t understand, tell me. I have never known and never hope to know any girl so perfect in every way as you are, so you may be sure that you are in no way responsible for what I said in the first of my letter.

I will surely send you a lock of my hair in a few days.

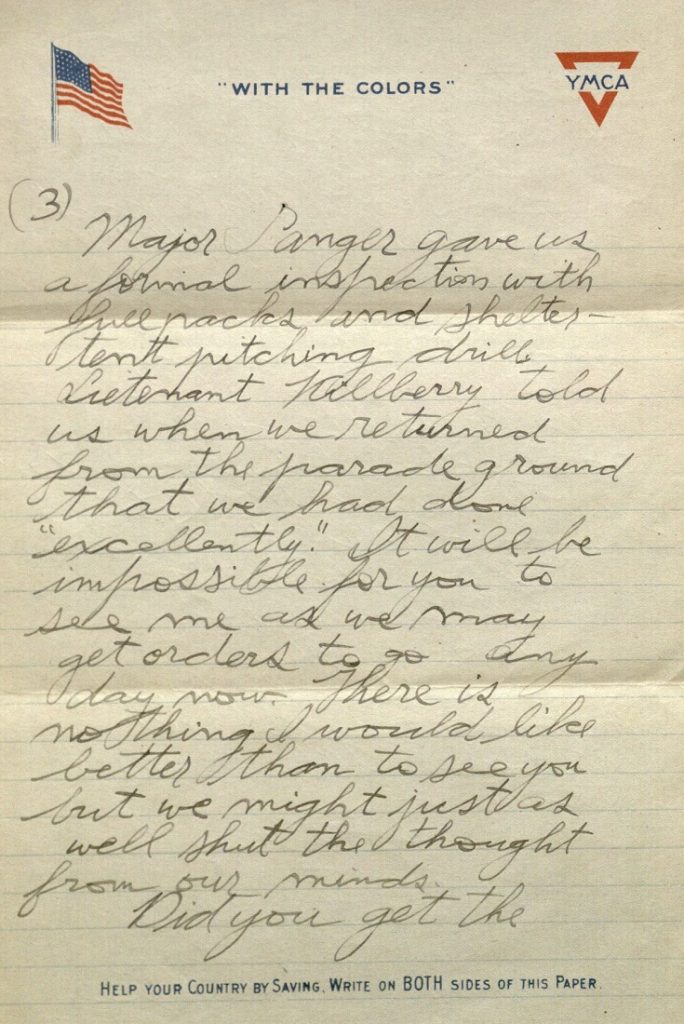

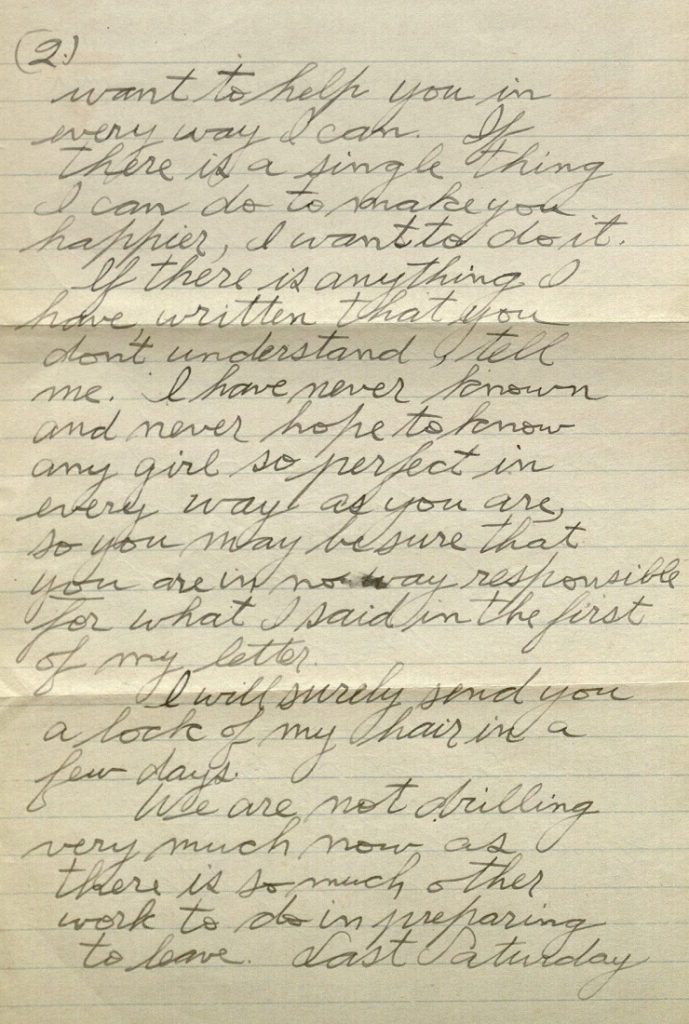

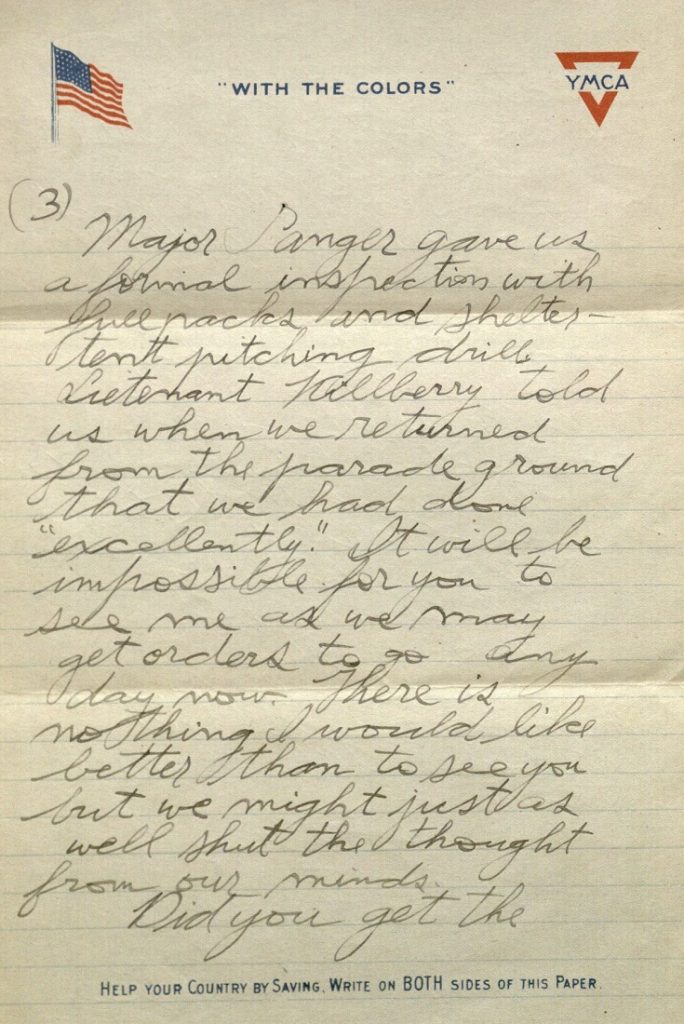

We are not drilling very much now as there is so much other work to do in preparing to leave. Last Saturday Major Sanger gave us a formal inspection with full packs and shelter-tent pitching drill. Lietenant Killberry told us when we returned from the parade ground that we had done “excellently.” It will be impossible for you to see me as we may get orders to go any day now. There is nothing I would like better than to see you but we might just as well shut the thought from our minds.

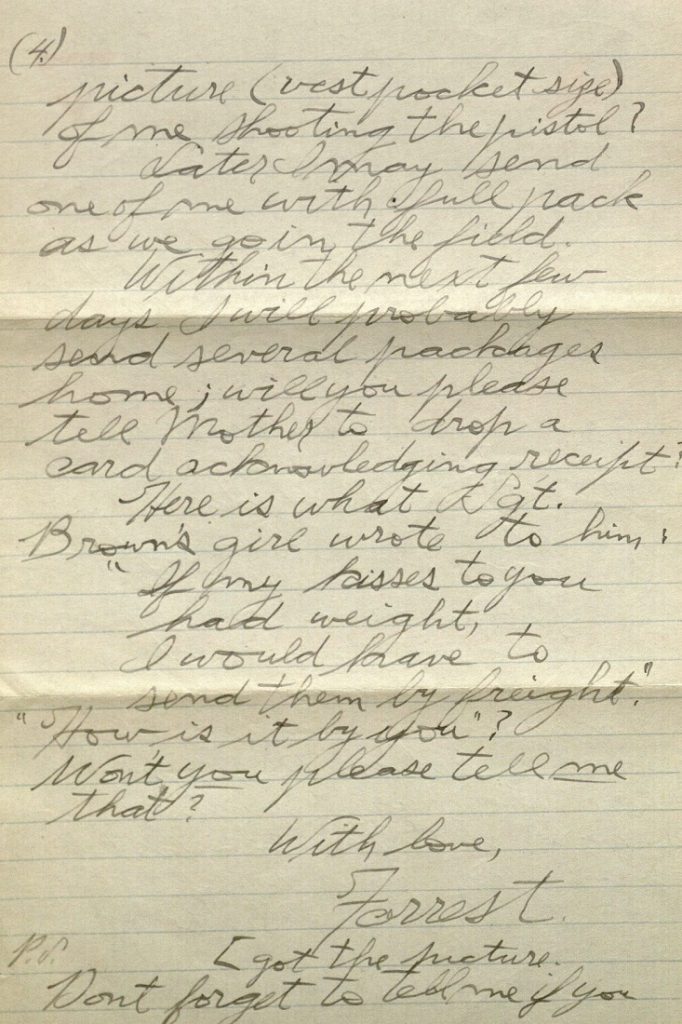

Did you get the picture (vest pocket size) of me shooting the pistol?

Later I may send one of me with full pack as we go in the field.

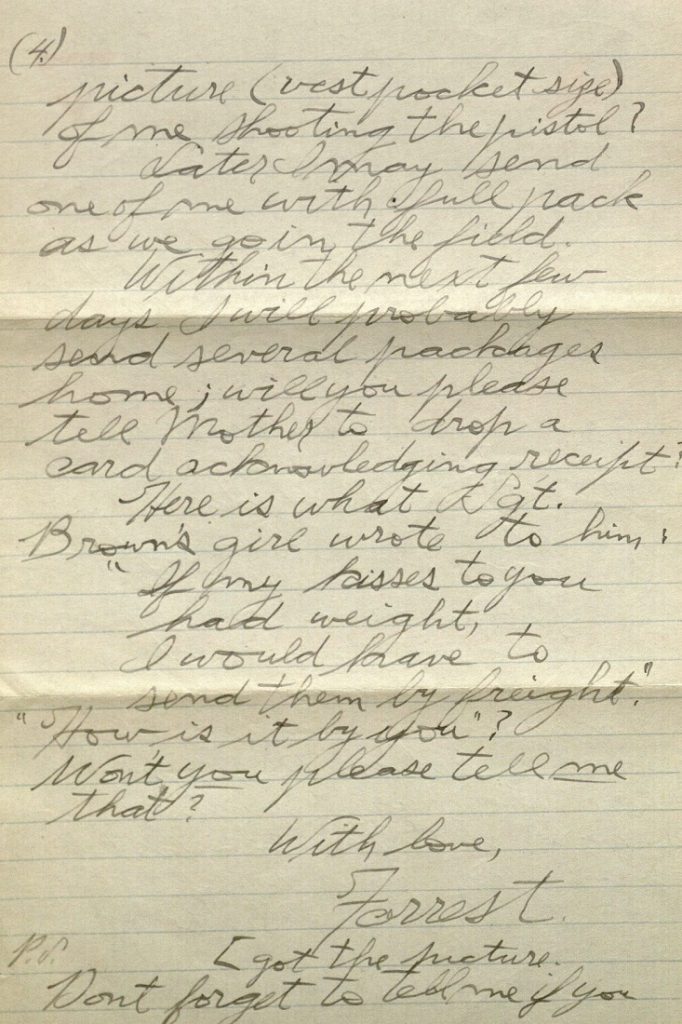

Within the next few days I will probably send several packages home; will you please tell Mother to drop a card acknowledging receipt?

Here is what Sgt. Brown’s girl wrote to him:

“If my kisses to you had weight, I would have to send them by freight.”

“How is it by you?”

Won’t you please tell me that?

With love,

Forrest.

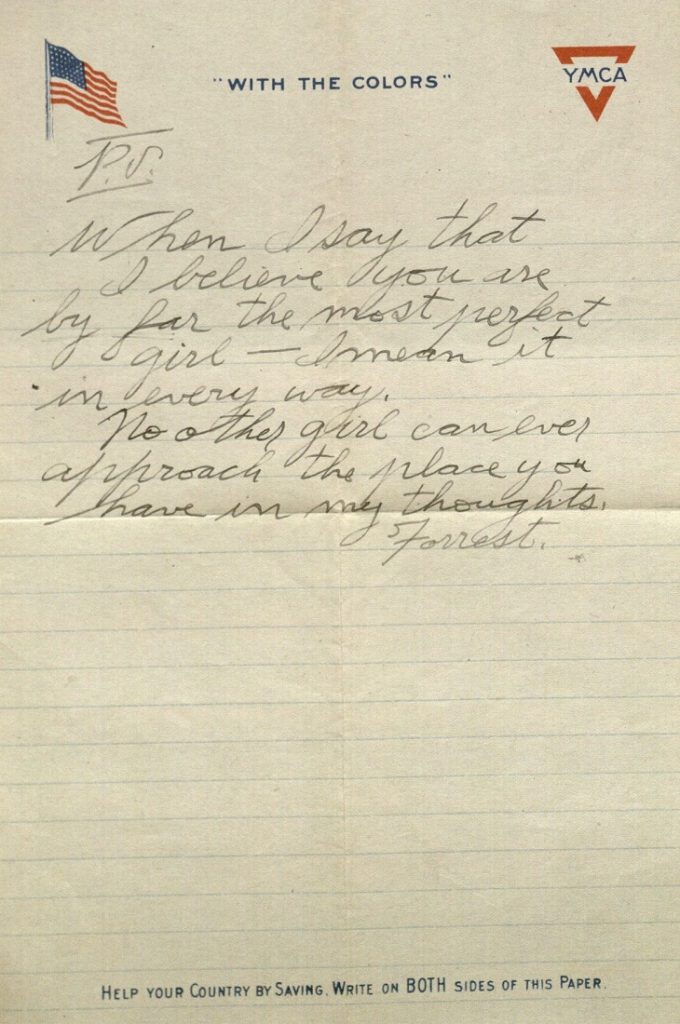

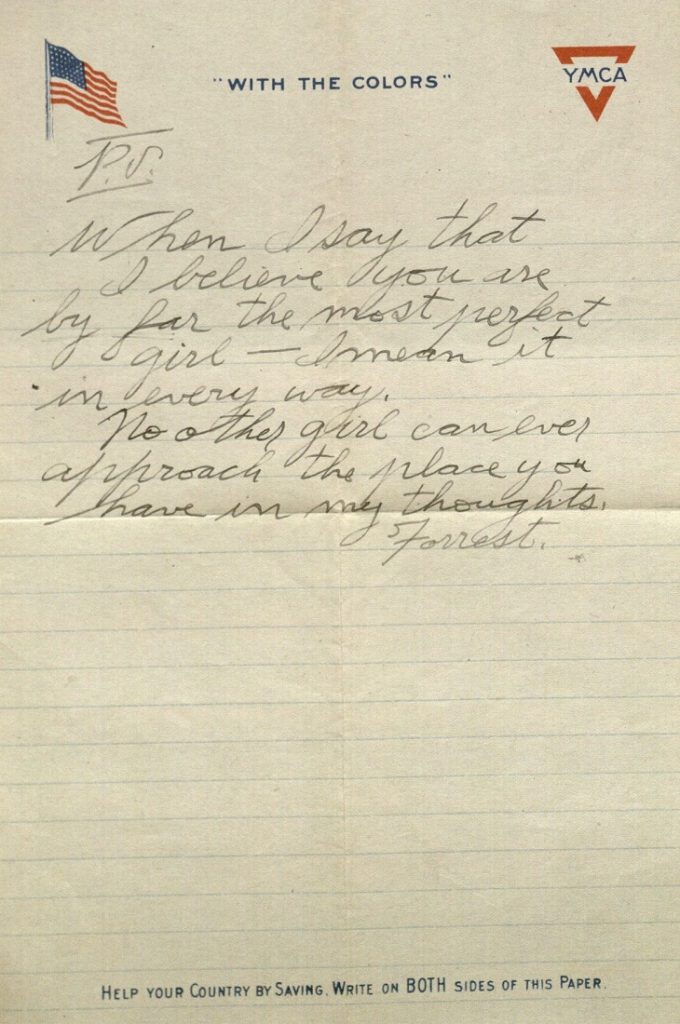

P.S. Don’t forget to tell me if you got the picture. When I say that I believe you are by far the most perfect girl – I mean it in every way.

No other girl can ever approach the place you have in my thoughts.

Forrest.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant