A true account and declaration of the horrid conspiracy against the late king, His present Majesty, and the government: as it was order’d to be published by His late Majesty – Thomas Sprat’s official account of the failed 1683 Rye House Plot to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and successor) James, Duke of York – is no doubt a fascinating and dramatic tale of intrigue. As a conservator, however, I’m interested in the stories that Spencer Research Library’s three different first-edition copies of this title tell through their physical condition and bindings.

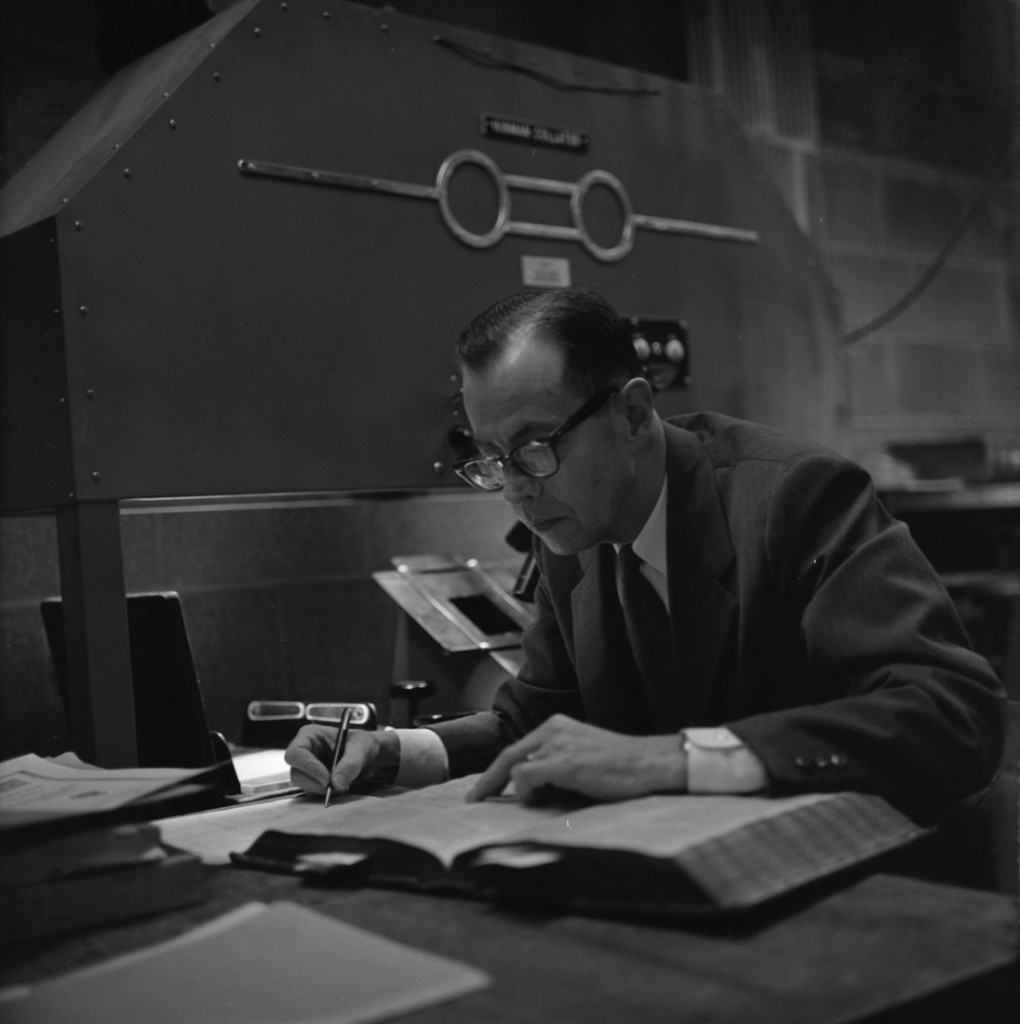

Two of the three copies recently crossed my bench in need of treatment, and when I looked up their catalog record I noticed that there was a third copy at Spencer, so I pulled that one from the stacks in order to examine them one next to the other. It was so much fun to compare the three volumes and to imagine how they’d begun their lives all together in the same place – Thomas Newcomb’s print shop – before being sold and going out into the world on their various journeys, only to arrive back together again in our stacks over three hundred years later, each bearing the distinct marks of its own life of use. I’ll refer to them as Copy 1 (E242), Copy 2 (E242a) and Copy 3 (E3324). Let’s do some wild comparatively tame speculation about the life stories of these books.

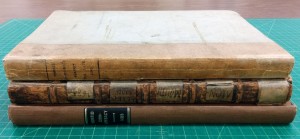

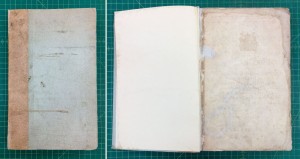

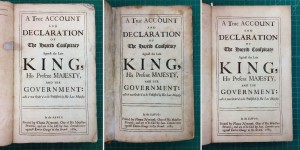

Spencer Research Library’s three copies of the True account of the horrid conspiracy: E242 (left), E242a (center), and E3324 (right). Click image to enlarge.

View of the spines of the three volumes: E242 (top), E242a (middle), and E3324 (bottom). Click image to enlarge.

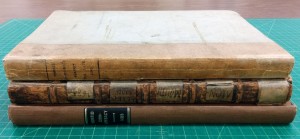

According to the practice common at the time, it is likely that all three of these copies left the printer, and maybe even the bookseller, in an unbound or partially-bound state, or possibly in temporary bindings; the buyer would then take the book to a bindery to be properly bound in his preferred style. Of Spencer’s three copies, only Copy 2 is in a binding roughly contemporary to the time of the book’s printing, though it’s hard to say if it truly is its original binding. It is a full leather binding with minimal decoration – a single tooled line along the edges of the boards – and it has obviously been heavily used; there is a good deal of general wear and tear to the text block and leather, and the front board was detached, held in place with gummed cloth tape. On the inside, the absence of pastedowns allows us to see the irregular turn-ins, the texture of the board, and the laced-in cords that all indicate the binding’s age.

Front board and front inside cover of E242a after treatment. Click image to enlarge.

The historic repair on this volume is cringe-inducing, in the way that all tape is offensive to conservators, but I admit to finding it somewhat charming as well, with its hand-scrawled title and date. This volume also had gummed cloth tape along the inner hinge; that tape was removed because it was causing damage to the paper, but the tape across the spine was left in place primarily because of the character that this oddly appealing feature lends to the volume. In addition to removing the tape from the inside of the book, I reattached the front board, reinforced the back board, and surface cleaned the text block where it was needed.

Handwritten labels on gummed cloth tape on the spine of E242a. Click image to enlarge.

Copies 1 and 3, having been rebound, may lack some of the old-book charm displayed by their edition-mate, but their bindings still tell (or at least suggest) something about the lives they have lived. We can only guess as to exactly when these volumes were rebound; my guess would be that Copy 1’s current binding is from the late 19th or early 20th century, while Copy 3 was bound somewhere in the first half of the 20th century (and I welcome thoughts and comments to corroborate or refute these estimates!).

When Copy 1 arrived in the lab for treatment, its paper spine was torn in several places and the case, which had been attached to the text block by just the flyleaves along a narrow strip down each shoulder, was nearly detached. The title page was torn and the text block was quite dirty, showing a great deal more wear than its newer case. This binding provides some measure of protection for what was seemingly a much-used volume, but the binder didn’t take extra steps to clean or mend the text block; this is a very utilitarian case binding. As part of its treatment, I mended the case, reinforced the case attachment to the text block, surface cleaned the most soiled parts of the volume (text block edges and the first and last several pages), and mended the tears with Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste.

Front cover and front inside cover of E242 after treatment. Click image to enlarge.

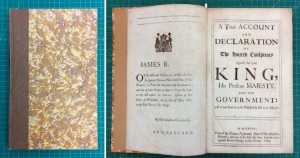

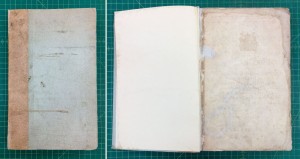

Copy 3, by contrast to the other two, is in very good condition; its text block is significantly cleaner and its binding is sound, probably the work of a commercial bindery or workshop. While any traces of a historic binding are lost, the information contained in the volume has been preserved, which some would argue is ultimately the most important thing. Still others might assert that its current binding can still tell us a lot about what readers, institutions, and book collectors value in the books they use/collect and how those values inform decisions such as how and whether to rebind a volume. Copy 3 does not appear to have been nearly as well-used as its mates, or perhaps it is just that it was not as ill-used – the good condition of its text block may be a sign that its owner(s) simply took very good care of it. Its modern library-style binding is not especially attractive, but it does its job well: it protects the text block and doesn’t cause it any harm.

Front cover, dedication, and title page of E3324. Click image to enlarge.

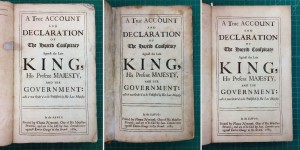

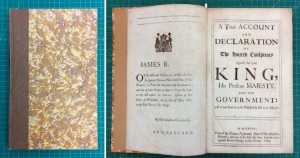

I have focused so far primarily on the bindings of these volumes, but before I conclude I want to point out an interesting printing detail on the title pages. Here are the three title pages side by side:

Title pages of True account of the horrid conspiracy: E242 (left), E242a (center), and E3324 (right). Click image to enlarge.

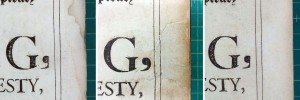

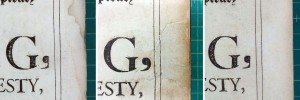

If you look closely, you can see that there’s a printing error on the large comma following the word “KING,” except on the title page of Copy 2, in the middle. Here’s a closer look (click image to enlarge):

At some time in the past, Copy 2’s title page sustained a small loss at the fore-edge, including part of the comma and the double border lines, and someone had filled the loss by lining the entire page with a piece of plain paper. This person (or perhaps some other, later person?) then drew in the missing lines and filled out the comma with ink. Was this the same person who applied the tape and handwritten labels on the spine of Copy 2? We shall never know, but it certainly is fun to wonder.

Angela Andres

Special Collections Conservator

Conservation Services

![Front cover of the Thompson Brother’s Fireside Library edition of Jane Eyre: an Autobiography with an illustration of Charlotte Brontë, [Nov. 1891?].](http://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OHegarty_C2307.jpg)