Context Matters

October 24th, 2022Like many institutions, KU Libraries (KUL) has come a long way in recognizing that we are not neutral and that our collecting practices, descriptive traditions, and operations are often not nearly as inclusive as we would like them to be. We have much, much further to go, but we are taking steps where we can. Libraries do not move quickly or easily when large-scale systems are on the line.

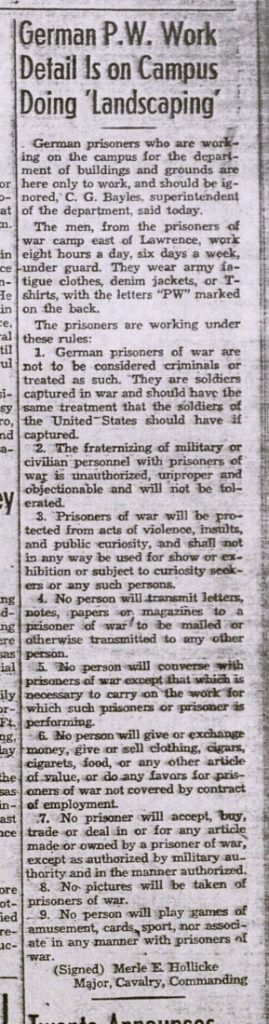

Realizing we should communicate transparently about our collections and practices, Spencer Research Library colleagues agreed we didn’t want to “disclaim” anything; we do not want to deny our responsibility to cover perceived liability or avoid a lawsuit. In fact, we are proud of our collections and the hard work that has gone into building them for decades. But in the world today, where images can be shared immediately, without context, and where intention is rarely assumed to be good, it was important to try to explain our work to those who might encounter our materials virtually.

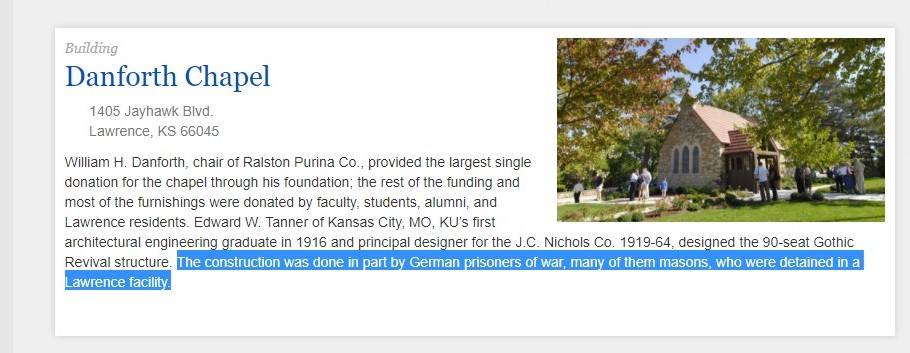

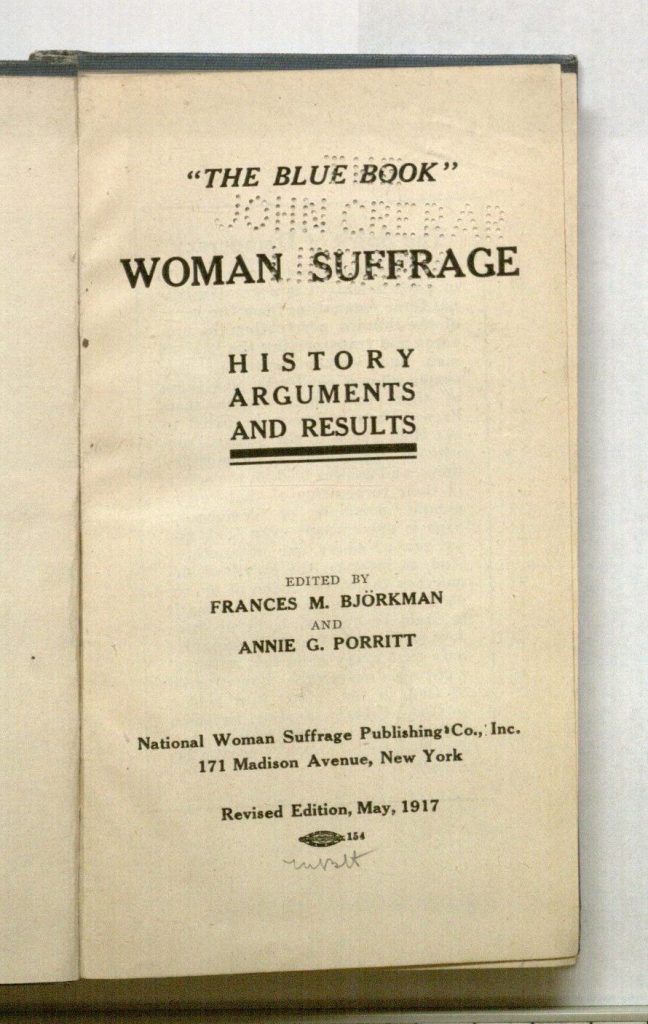

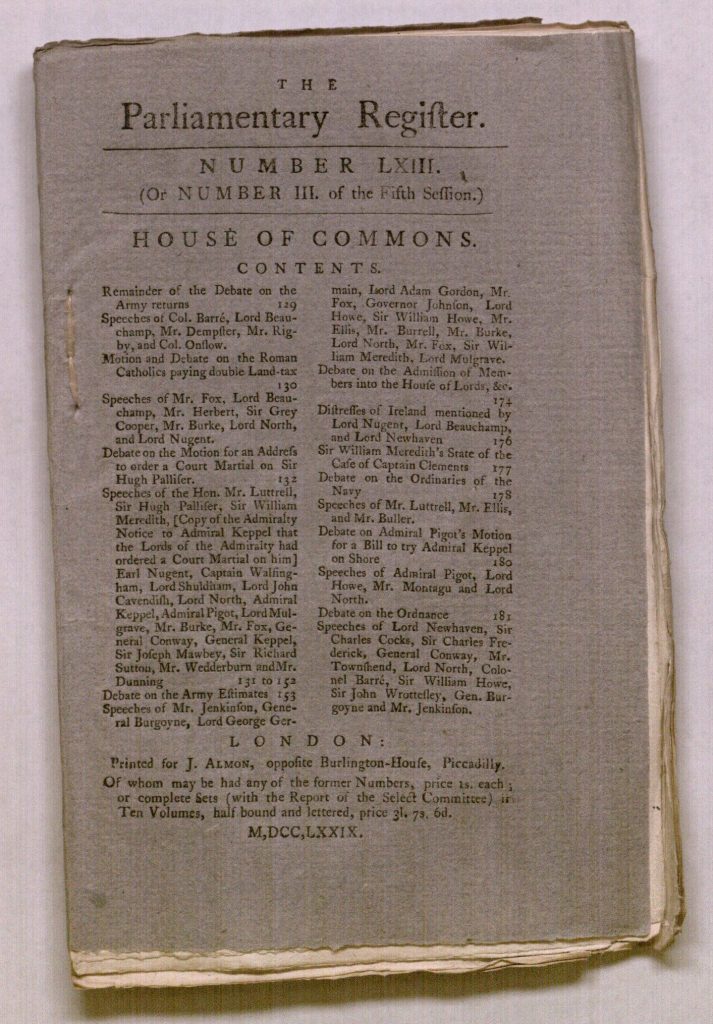

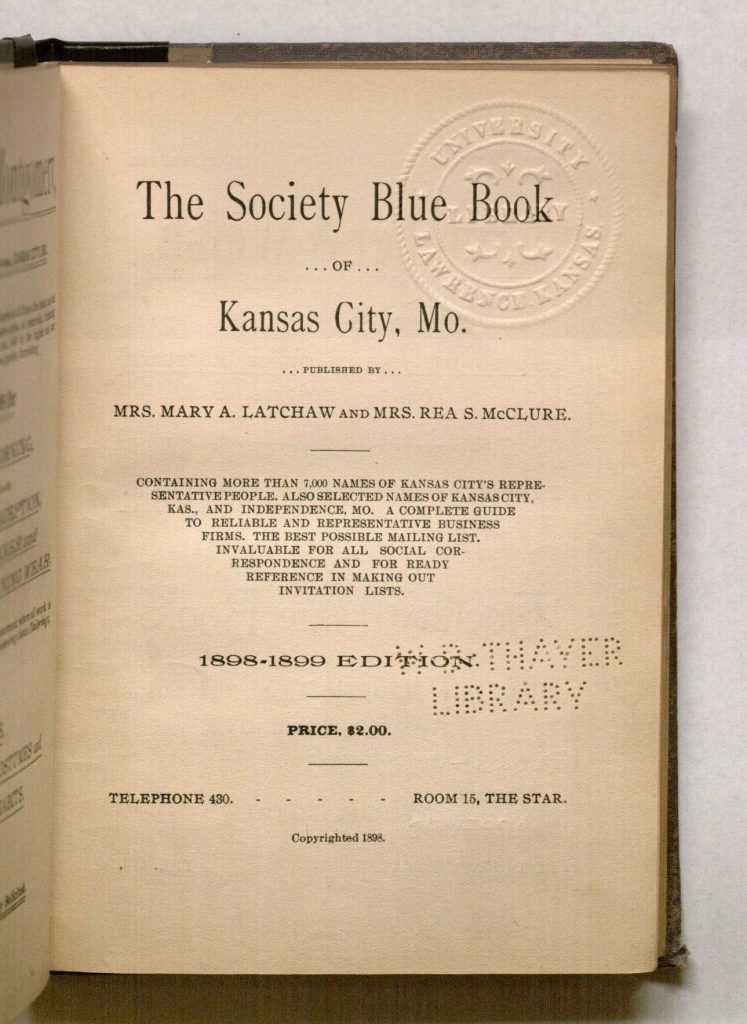

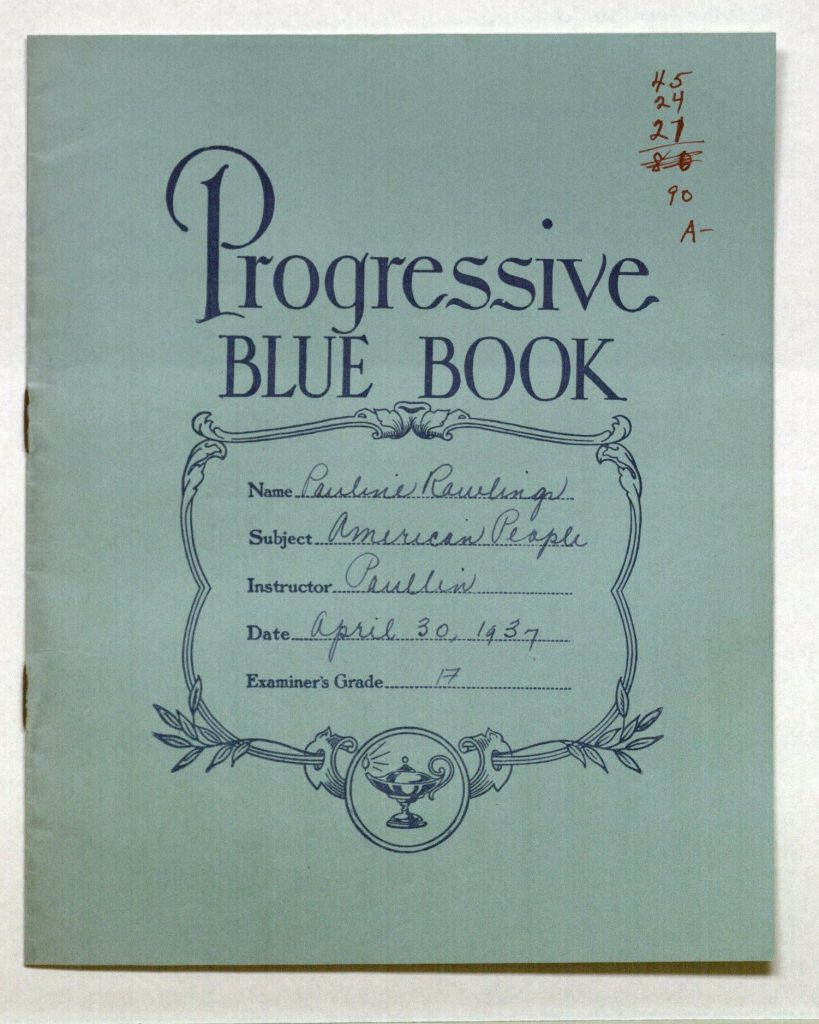

Our reasons for collecting disturbing or offensive materials and making them available to users are grounded in library and archival best practices, our mission, and the mission of the larger university. In fact, sharing these materials with researchers, students, and the public around the world is our actual purpose for existing. If we don’t collect these materials, many of the perspectives they capture may not be represented elsewhere. Ignorance and secrecy rarely advance the best of our humanity.

But these reasons might not always be clear to folks outside the library, so we wanted to strike a balance between 1) providing information about why objectionable or even harmful material can be found in our library and 2) acknowledging that, even if we have good reasons to collect and share these materials, they have the potential to cause harm to users. Like libraries everywhere, we began by looking at what other institutions were doing.

We decided to call this work “contextual statements,” to make clear that we want to provide the context of our collections. We wanted to articulate our mission in a way that acknowledges that libraries are doing hard work in trying to capture voices and tell stories, even though we struggle to do enough with limited resources.

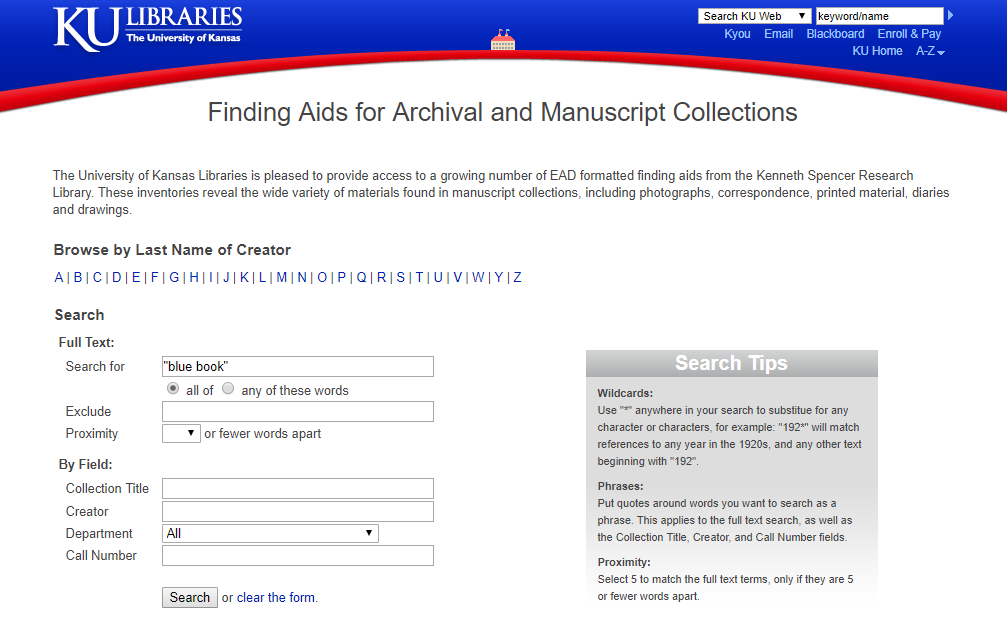

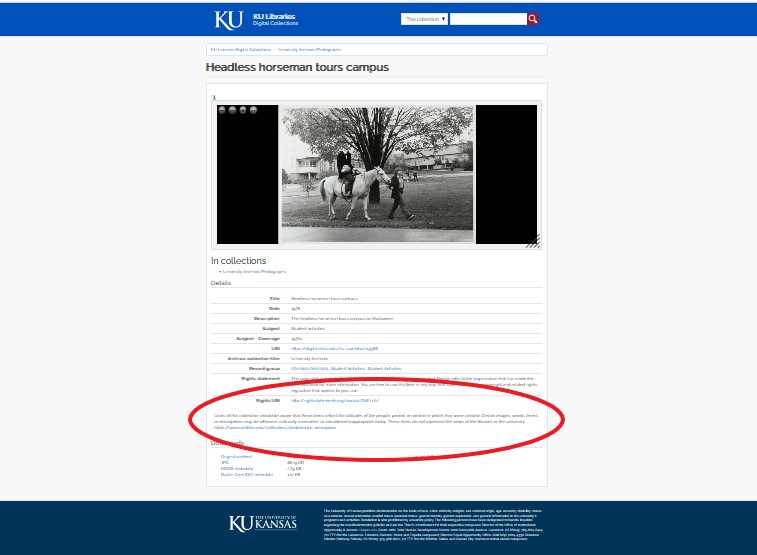

The first step was to add a phrase to all images from our collections in KU’s digital repository, where digitized versions of our collection materials are increasingly being made available to the world. This language was drafted by a small group and went through many revisions by the Spencer collections group, and was implemented by our colleagues in KUL Digital Initiatives:

“Users of this collection should be aware that these items reflect the attitudes of the people, period, or context in which they were created. Certain images, words, terms, or descriptions may be offensive, culturally insensitive, or considered inappropriate today. These items do not represent the views of the libraries or the university.”

We also decided we needed a longer statement about our collections, and added more information to our previously published collection development statements, also freely available. Initial work came from Head of Public Services Caitlin Klepper and Head of Manuscripts Processing Marcella Huggard with input from a group from across Spencer.

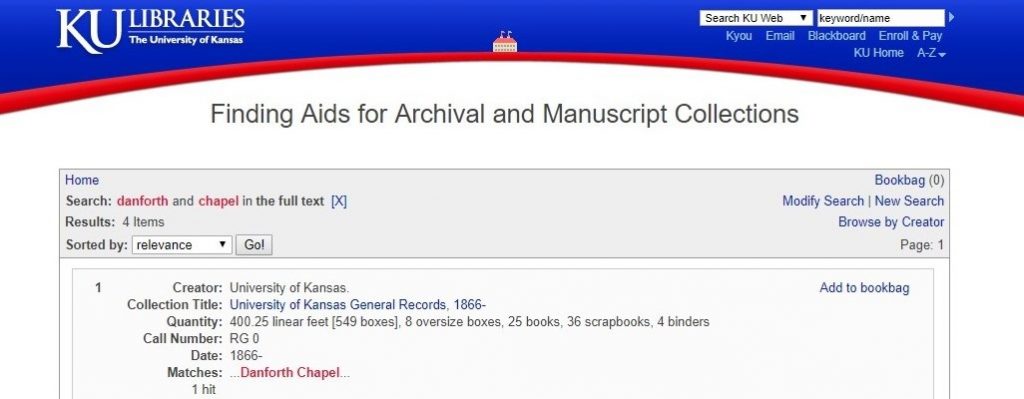

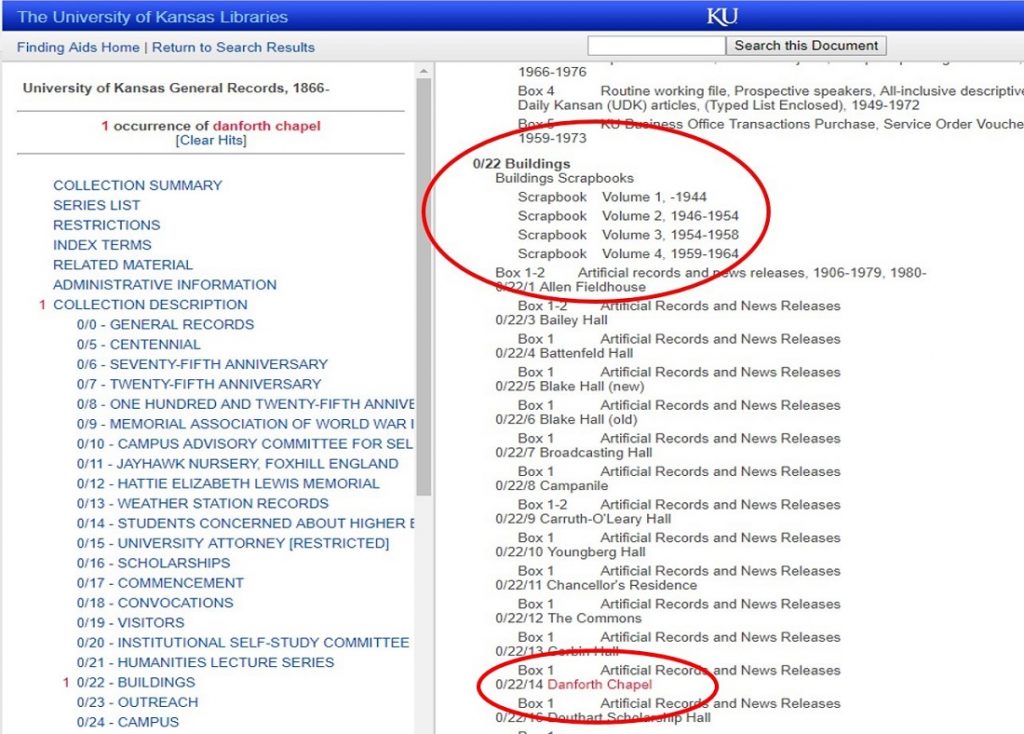

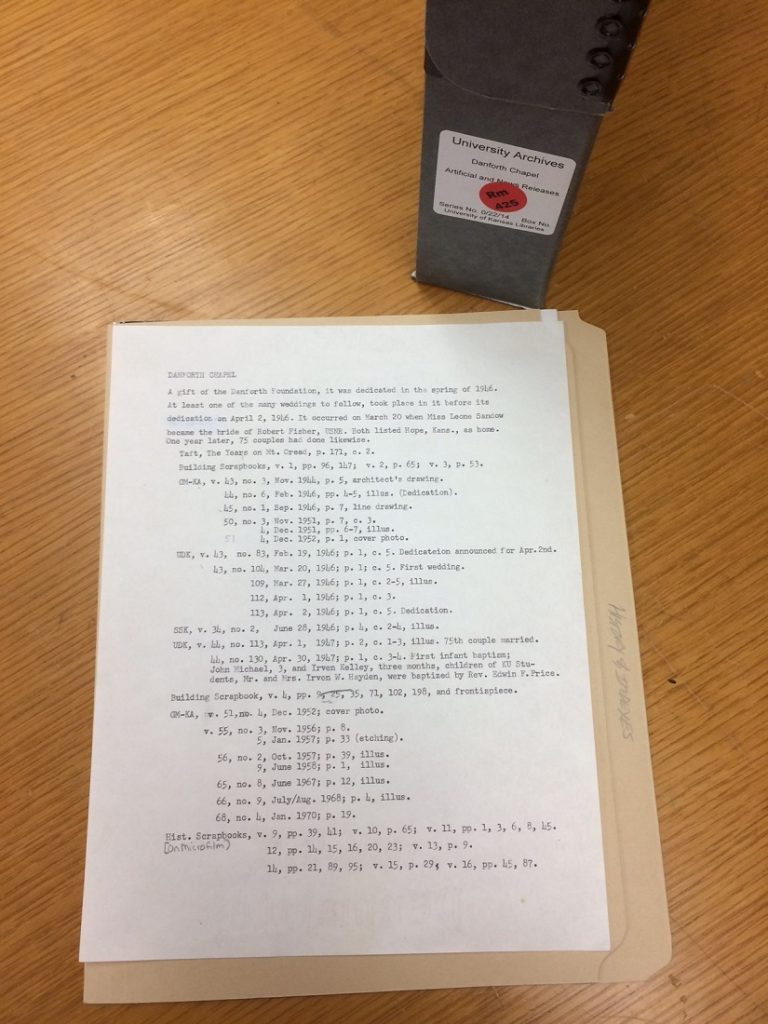

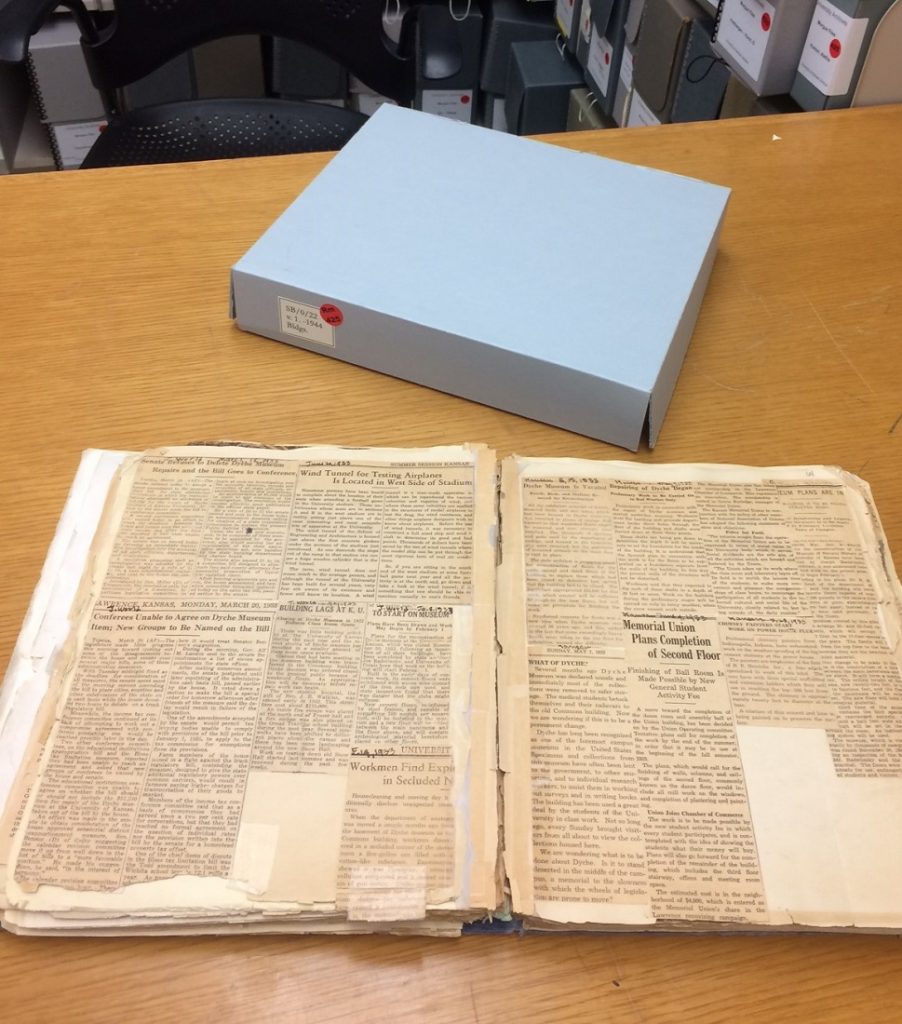

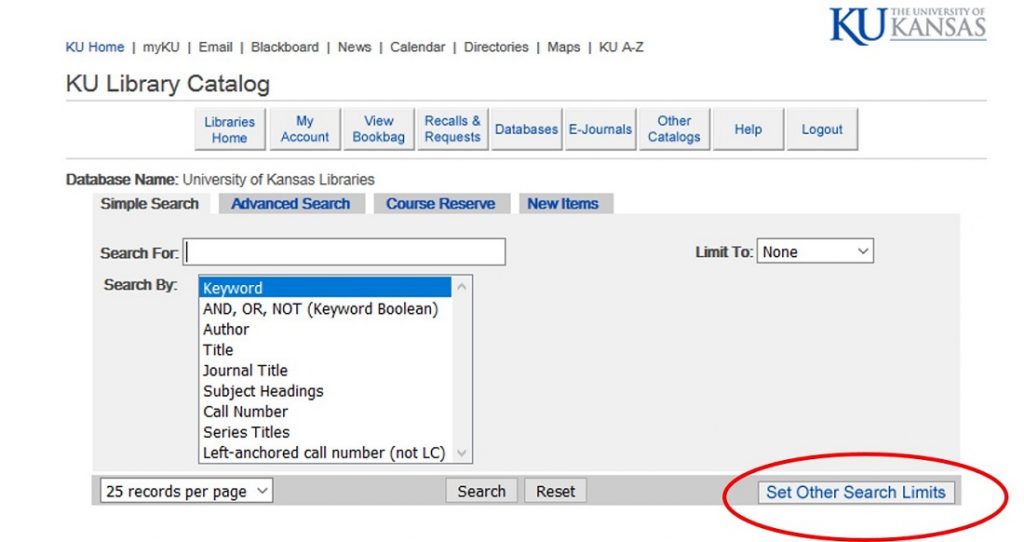

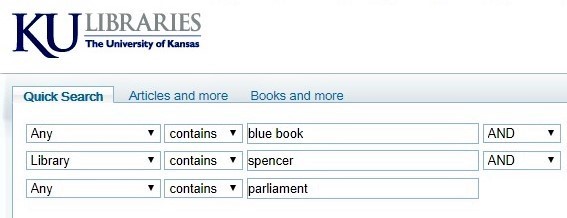

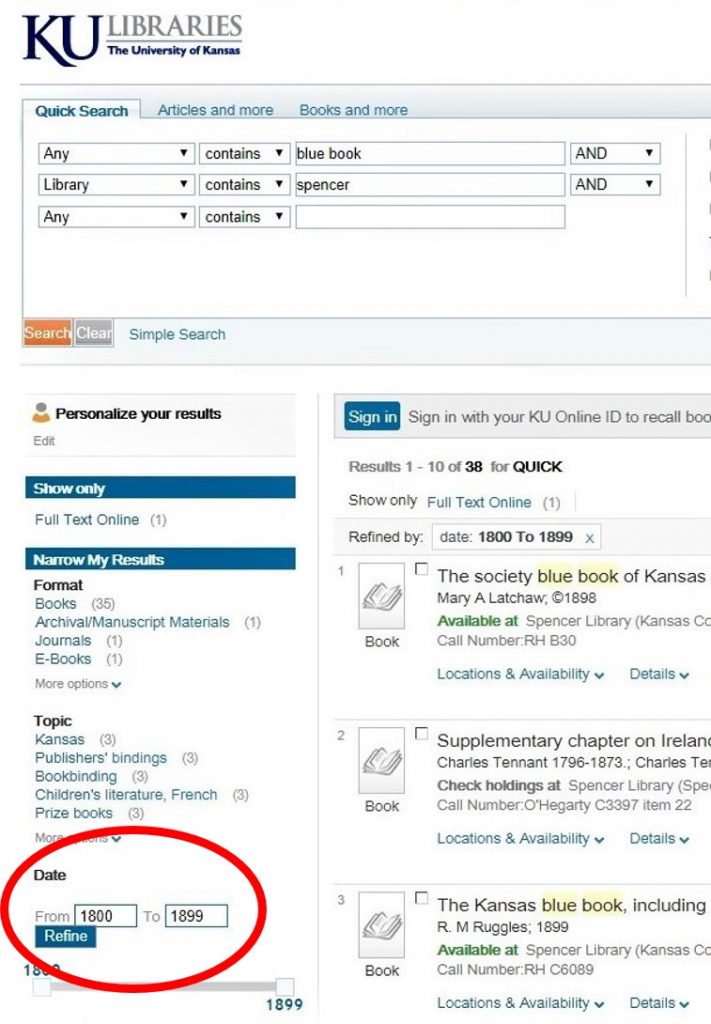

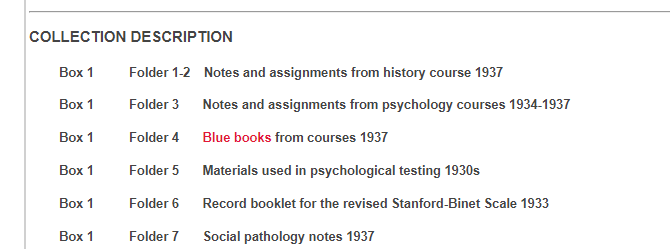

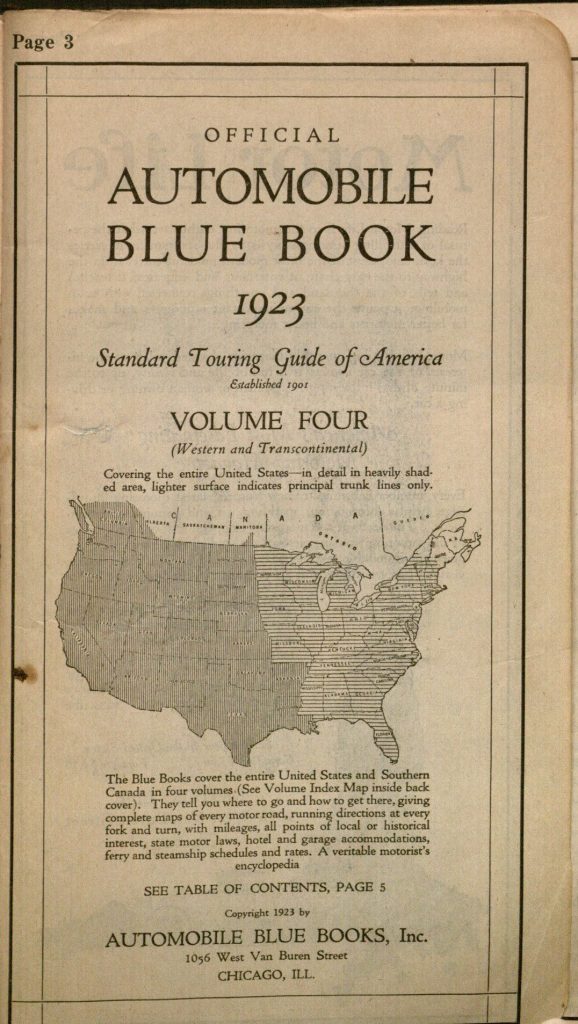

Finally, we saw an opportunity, as have many of our peer institutions, to expose the work of description, a professional specialty that has long been hidden behind card catalogs and filing cabinets, frequently in the basements of buildings and at the end of a long series of tasks that take collections from the donor’s attic to the loading dock and to the shelves (or laptops). We published a statement about that as well, initially drafted by Caitlin Klepper and Marcella Huggard, based on the work of other institutions.

In all of this, we relied heavily on the good judgement and best efforts of colleagues at peer institutions. We realize that every environment is unique, so we tailored it to the KU world, talking with colleagues and, where we could, members of our communities. We hope to get feedback as we go, as we begin a larger conversation with those who use our collections in various ways—about what we collect and why, how we describe it, and how we use the impact of our collections to make a better, more just world.

Beth M. Whittaker

Interim Co-Dean, University of Kansas Libraries

Associate Dean for Distinctive Collections

Director of Spencer Research Library