Kansas City’s Douglass Hospital: The First Black Hospital West of the Mississippi River

February 23rd, 2022The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) founded the annual February celebration of Black History in 1926 and has identified “Black Health and Wellness” as the theme for 2022.

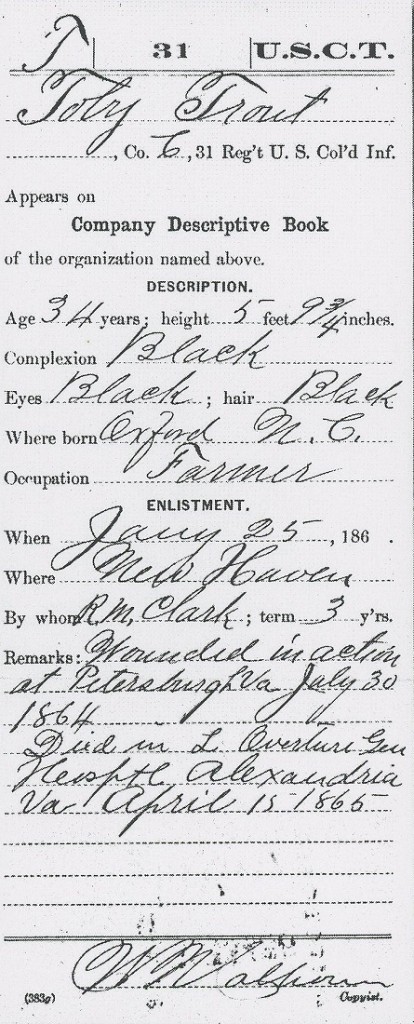

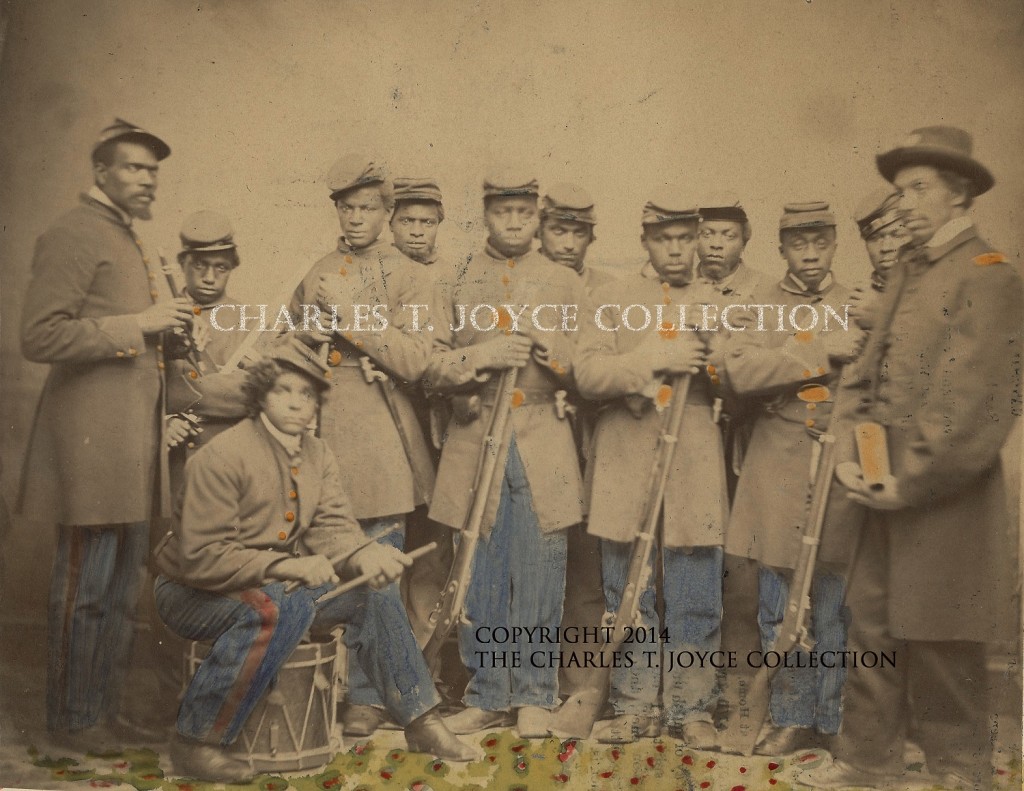

Until the 1960s, Black physicians and nurses in the United States were denied access to most hospitals, while Black patients were either not accepted or relegated to inferior, segregated areas in hospitals. From Spencer’s African American Experience Collections, I selected images and a few printed items to highlight the Greater Kansas City Black Community’s pioneering effort to defy “Jim Crow” practices by establishing the nation’s first Black community owned and operated hospital west of the Mississippi. It was also the region’s first modern hospital to welcome all patients equally regardless of their “race.”

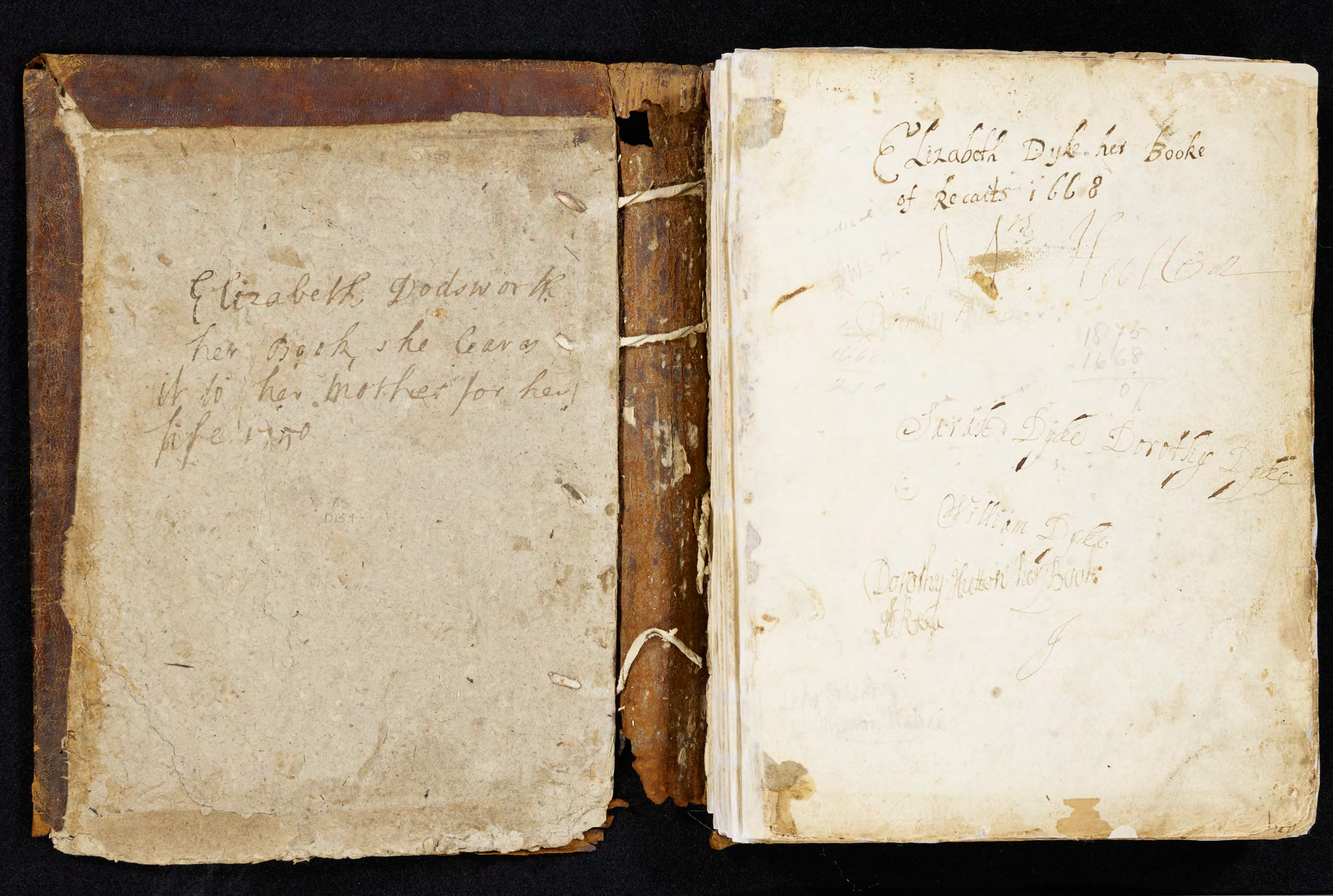

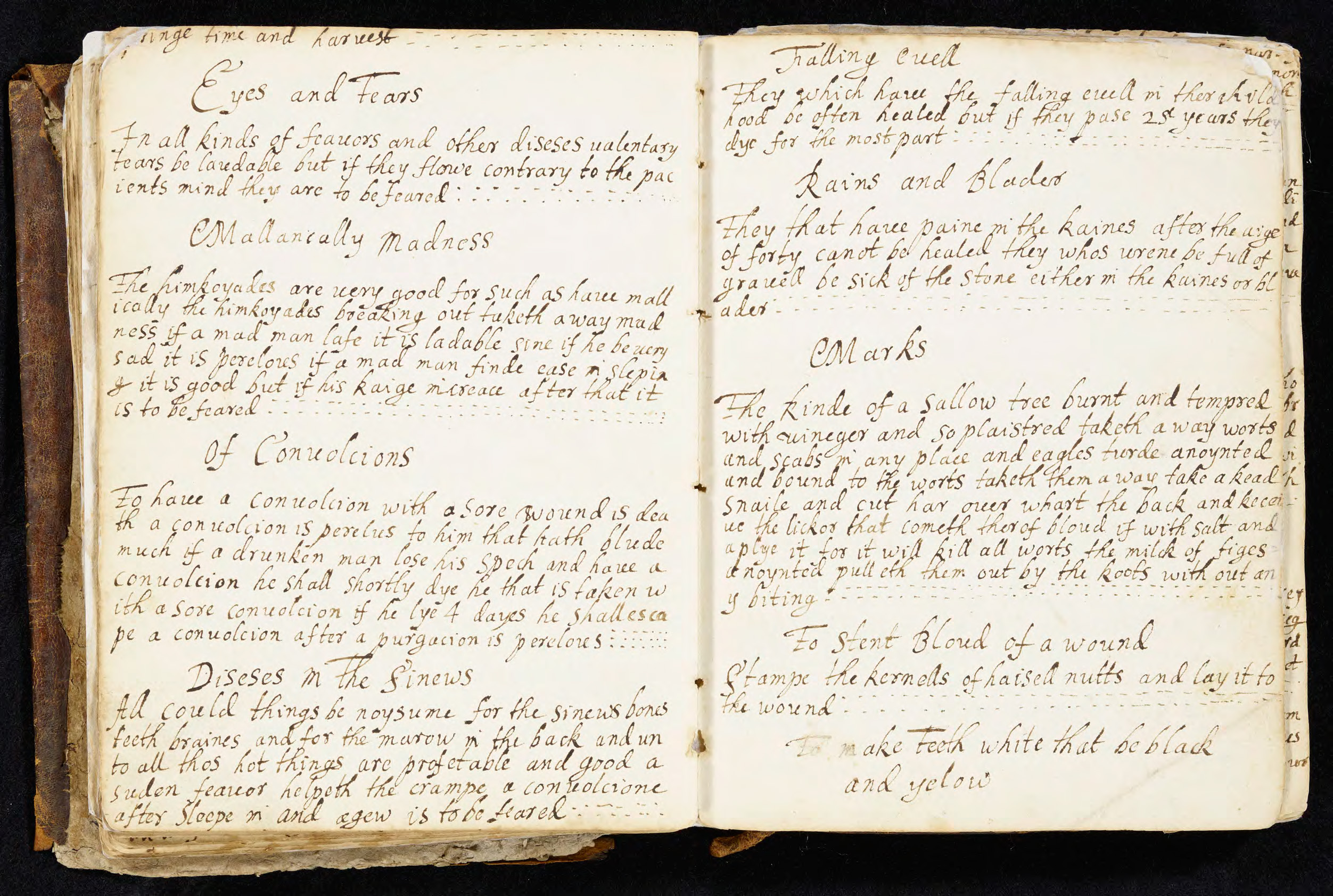

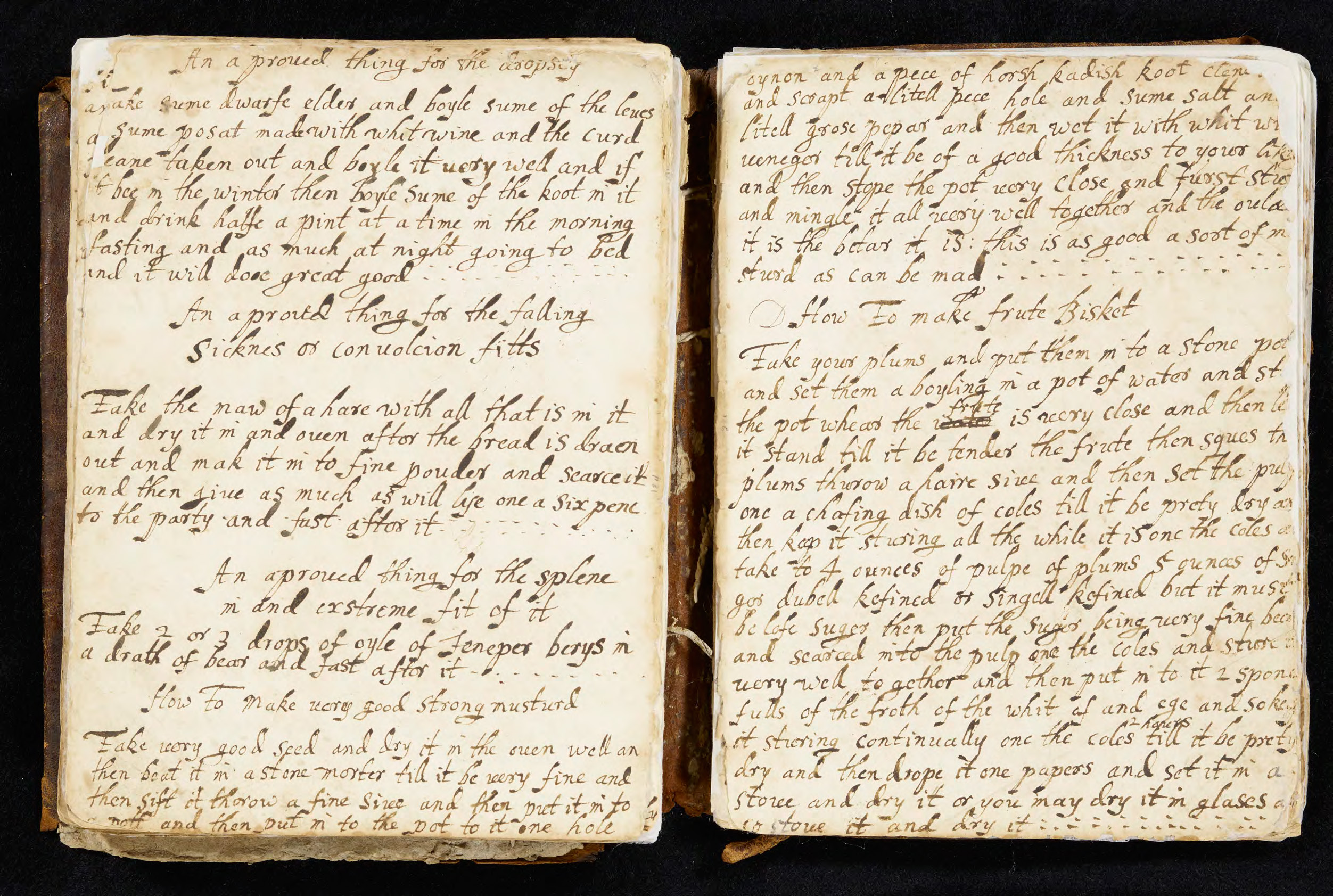

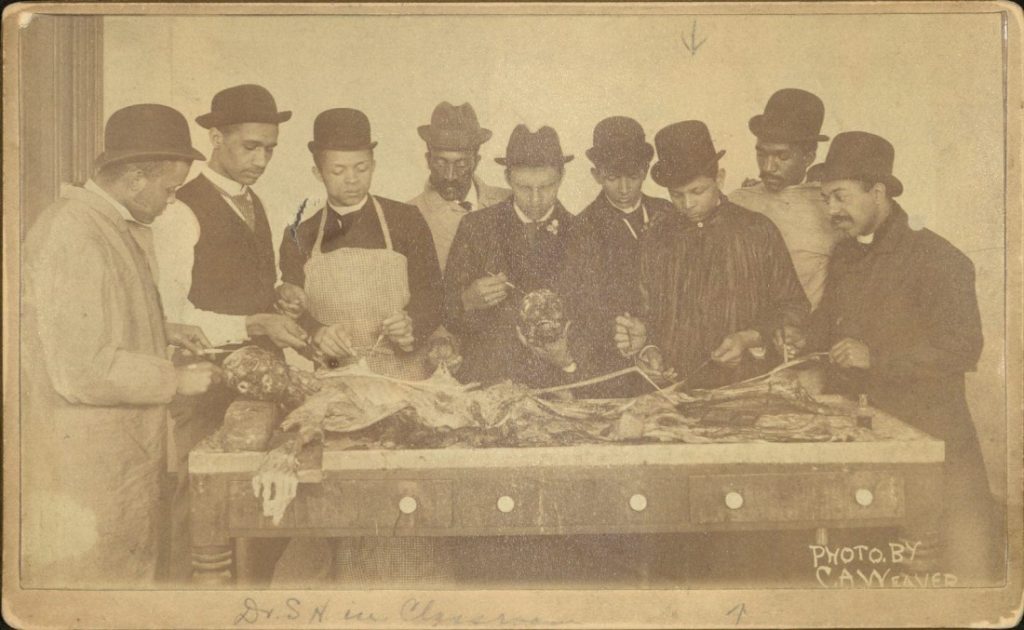

Organized by Black physicians and community leaders from Kansas City, Kansas (KCK), and Kansas City, Missouri (KCMO), Douglass Hospital opened its doors in December 1898 under the temporary supervision of Nurse Miss A.D. Richardson from Provident Hospital in Chicago. The building previously housed a white Protestant hospital. Fully equipped, it provided ten beds for patients on the first floor and a nurse’s quarters on the second floor. In 1901, the hospital’s first Nursing School exercise convened at First AME Church in KCK and its Nurse Commencement at the Second Baptist Church in KCMO.

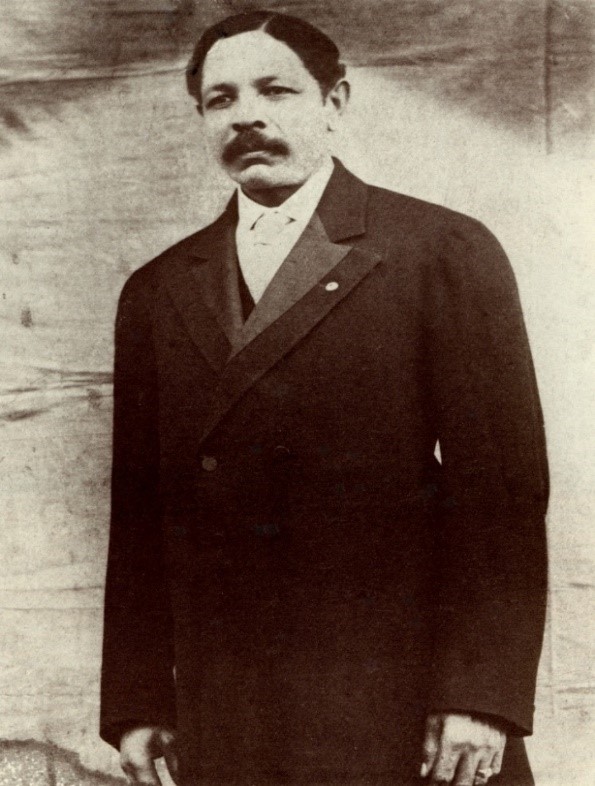

Dr. Thompson, the leading founder of Douglass Hospital, was the eldest of thirteen children born to Mr. Jasper and Mrs. Dolly Thompson in West Virginia. He earned his undergraduate degree from Storer College in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, and a medical degree from Howard University Medical School in Washington, D.C. After an internship in surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital in D.C., he moved to Kansas City, Kansas, where he developed a thriving private practice. He also served as the head of Douglass until he retired from practicing medicine in 1946.

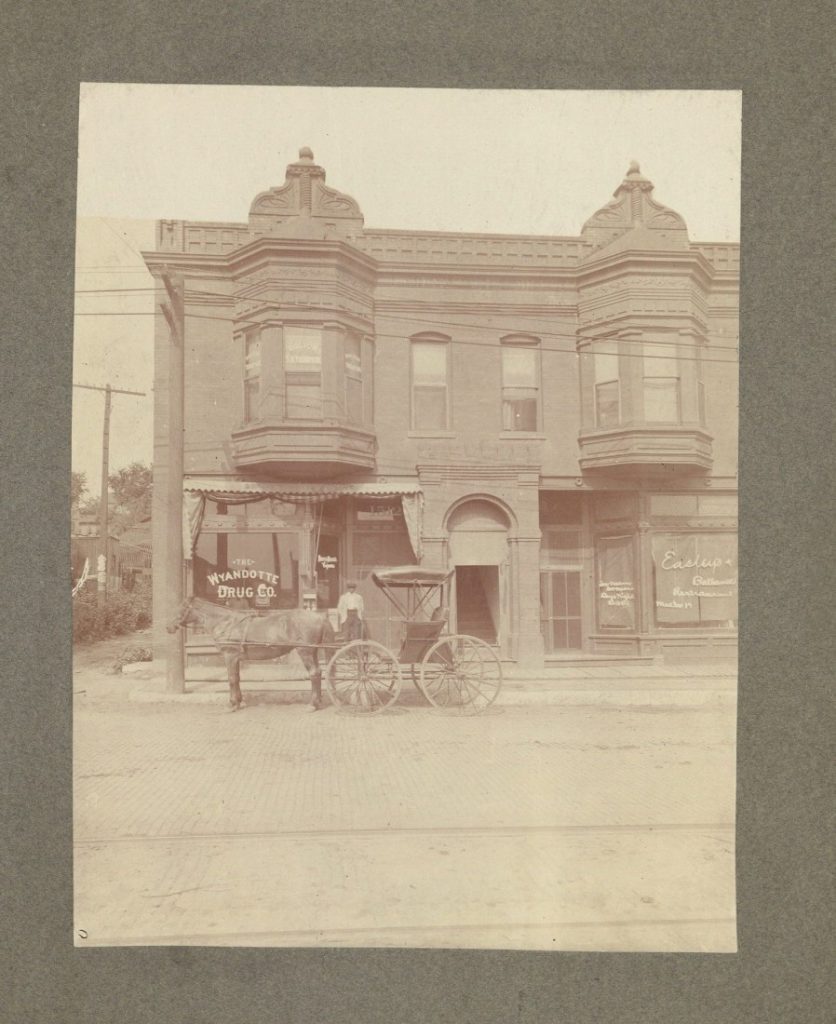

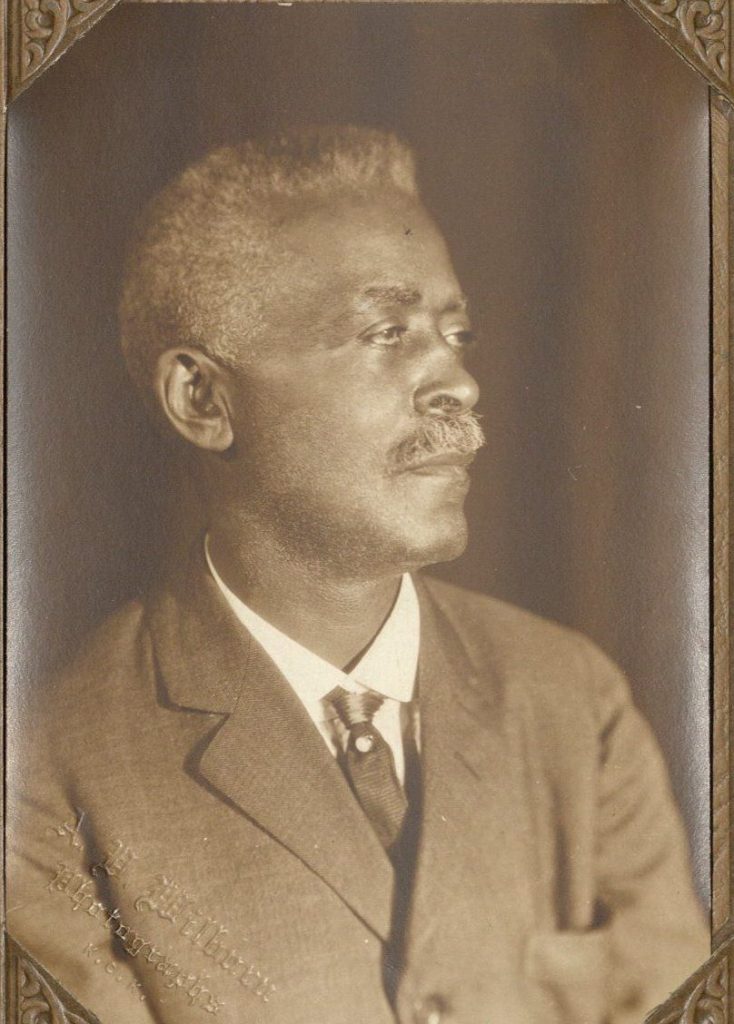

A native of Saline County in Missouri, Mr. Isaac Franklin Bradley was a co-founder and devoted community advocate for Douglass Hospital. After earning a bachelor of law degree from the University of Kansas in 1877, he moved to Kansas City, Kansas, where he established an active private law practice and served as the City’s Justice of the Peace (1889-1891) and the First Assistant County Attorney (1894-1898). Dedicated to Black collective advancement, Mr. Bradley engaged in a variety of community business enterprises, served as a charter member of the 1905 Niagara Movement (the predecessor of the NAACP), co-founded KCK’s Negro Civic League, and owned/edited the Wyandotte Echo newspaper.

(Douglass Hospital co-founder Dr. Thomas C. Unthank (1866-1932) in Kansas City, Missouri, also pioneered the development of General Hospital #2 in Kansas City, Missouri, the first Black Municipal Hospital in the United States in 1911.)

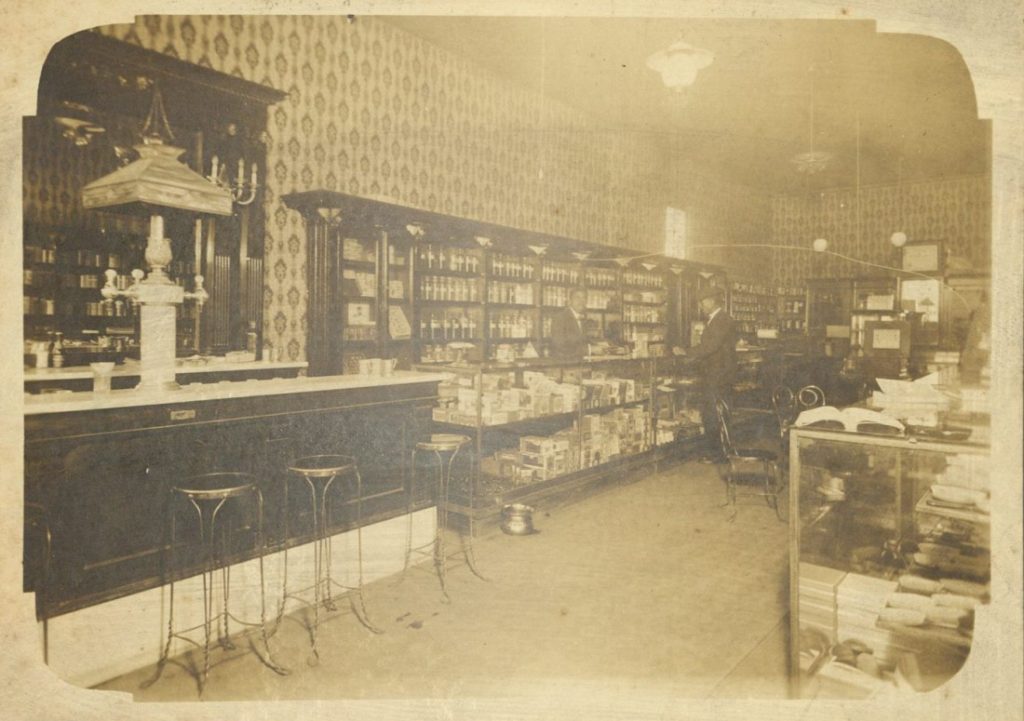

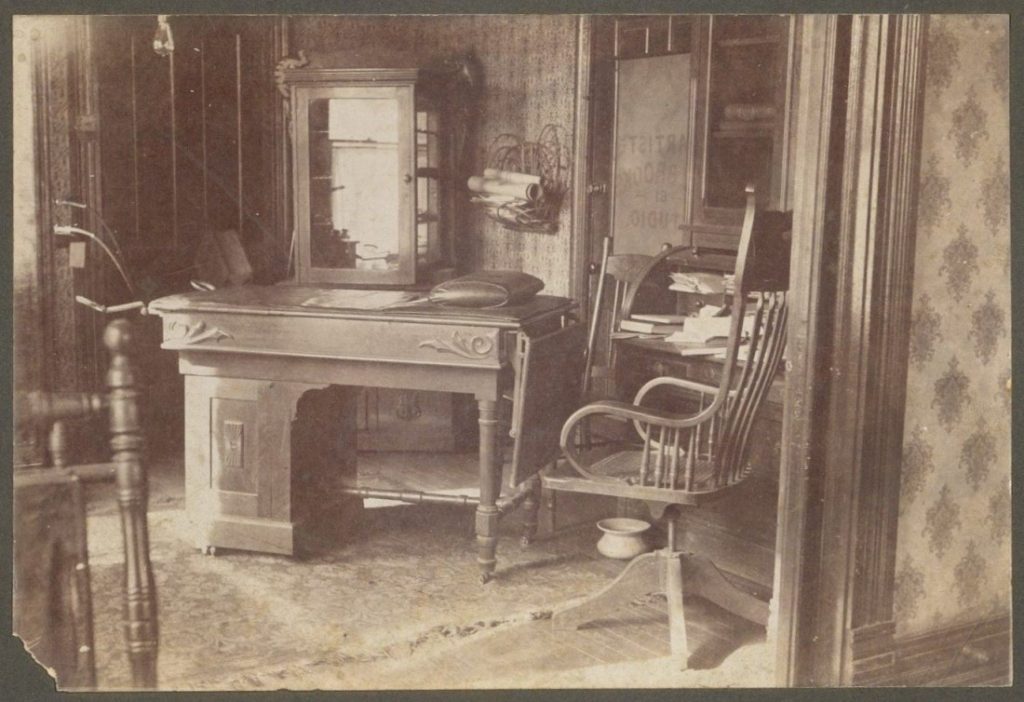

Once up and running, Douglass Hospital sparked the development of a nearby Black community owned and operated “medical” building.

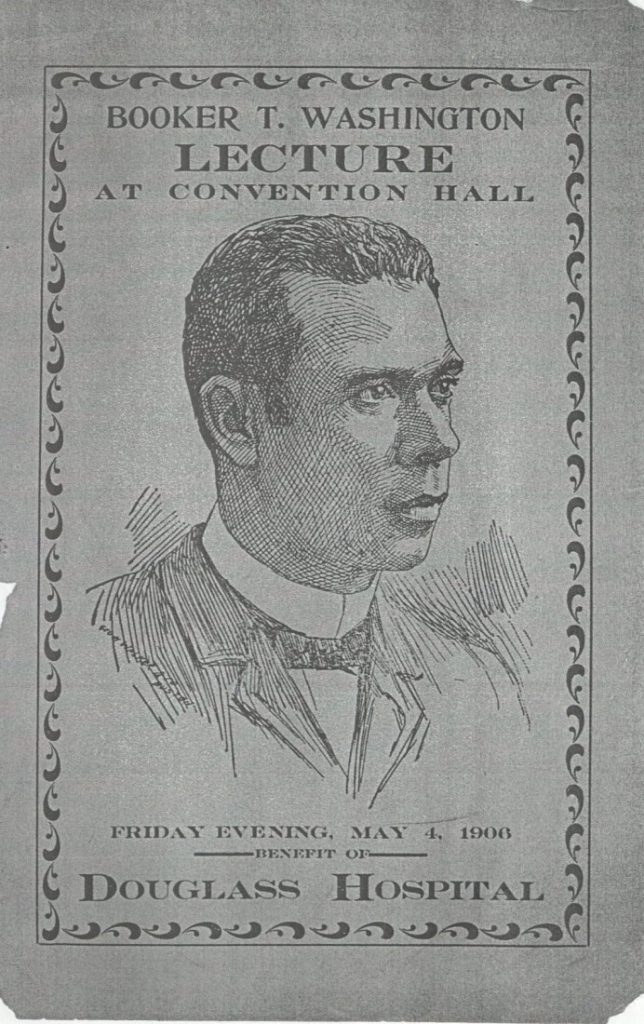

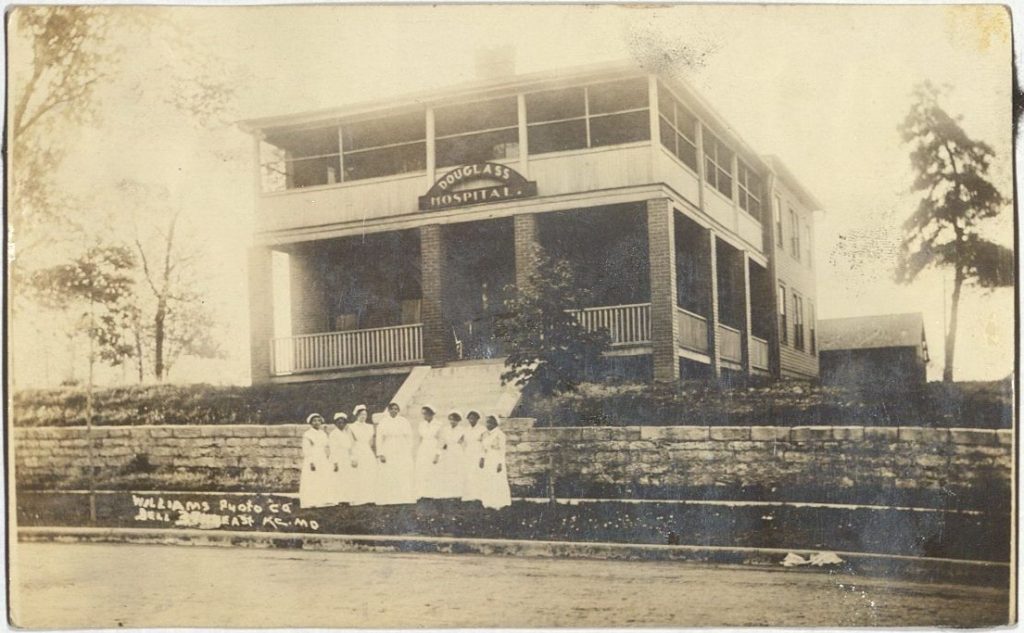

More than 6,000 people, Black and white, attended this Douglass Hospital fundraising event in Kansas City, Missouri’s Convention Hall to hear Booker T. Washington’s lecture. A year earlier, the hospital’s volunteer governing board and medical staff decided to move under the administration of the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s Fifth District led by Bishop Abraham Grant in response to the increasing costs and administrative needs required to maintain a modern hospital. After this event, Douglass paid its debts and enlarged its facility, as seen in this photo:

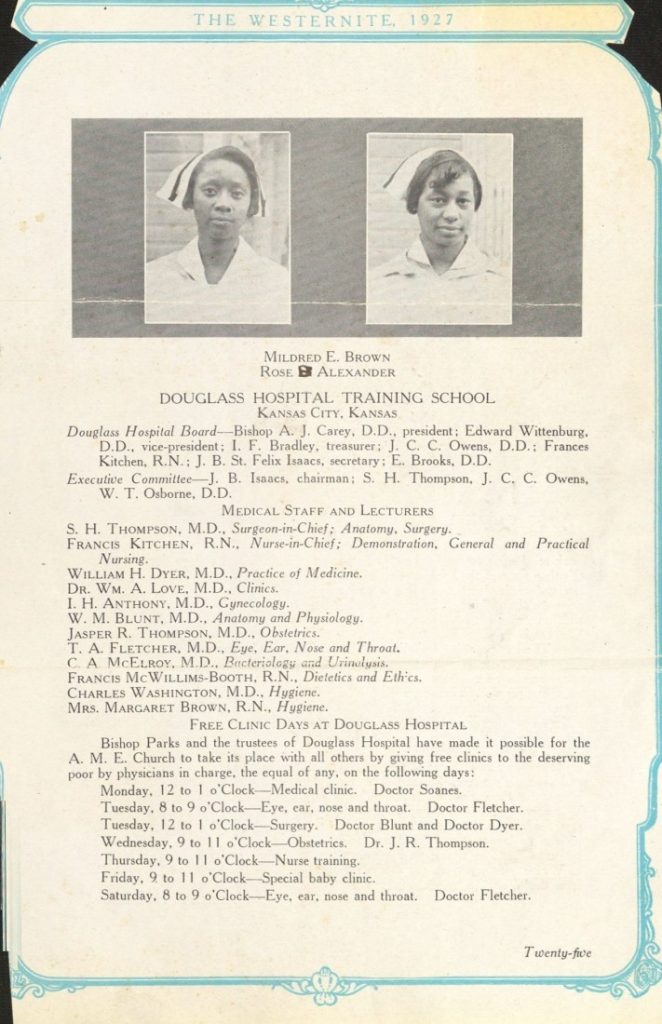

By 1915, the Douglass Hospital Nurse Training School was incorporated into the curriculum at Western University in Kansas City, Kansas.

To meet the hospital’s increasing number of patients, the Greater Kansas Black community organized a fundraising drive that led to the purchase of the former Edgerton Estate. The two-story, fifteen-room residence enabled the hospital to increase its capacity to twenty-five patients with two more small buildings for meetings and events. Douglass Hospital convened public programs during annual Negro Health Week in April and sponsored free clinics for ear, nose, and throat exams and sessions on medical care for babies.

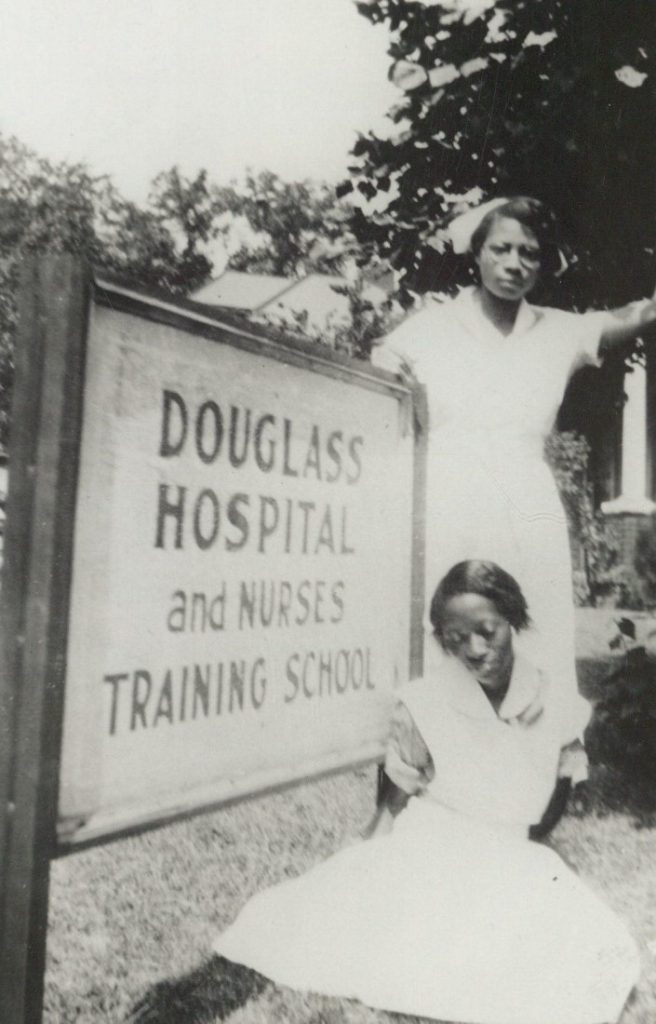

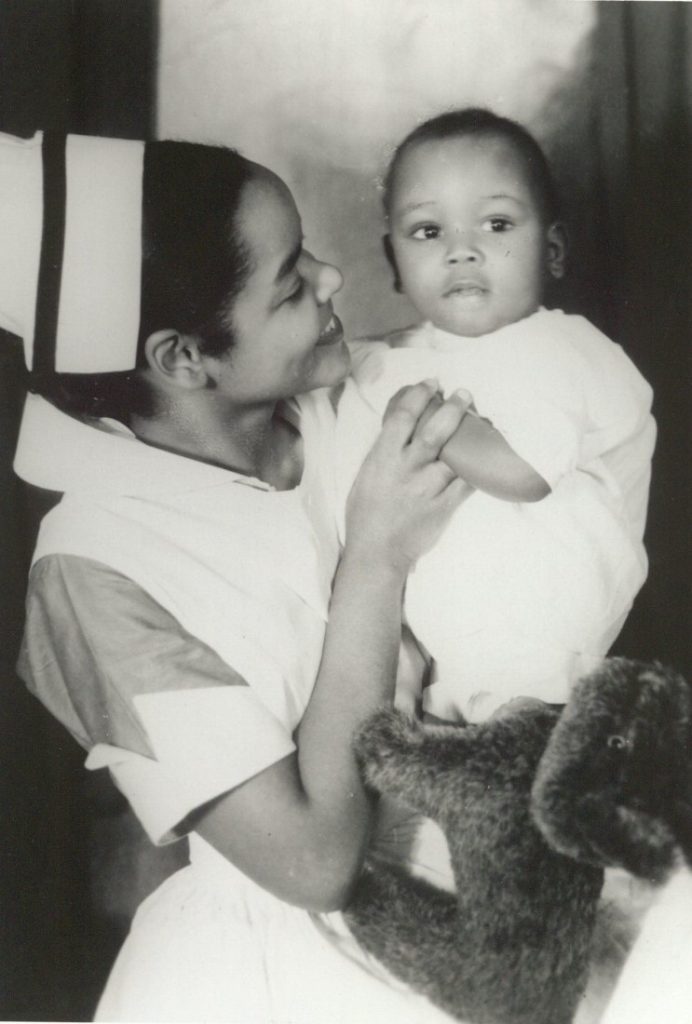

Douglass Hospital nurses delivered the ongoing care for patients, organized outreach activities, and managed the hospital’s ongoing need for more medical supplies.

During the 1930s the hospital experienced a steep decline in patients, staff, and funding. After graduating forty-three nurses during the last three decades, the Douglass Hospital Training School closed in 1937. However, with support from the Black and white Greater Kansas City communities and funding from the Federal government’s Hill-Burton Act for hospitals in 1945, Douglass renovated a three-story building on the former Western University campus to accommodate a fifty-bed hospital that included a bloodbank, lab, and obstetrics unit. On the building’s ground floor, visitors were welcomed in a spacious reception area.

By 1954, desegregation practices in Greater Kansas City’s white hospitals eventually forced Douglass to close its doors in 1977. Afterwards, the hospital’s last building was torn down and its records lost.

Deborah Dandridge

Field Archivist/Curator, African American Experience Collections

Kansas Collection