Manuscript of the Month: Charting a Late Fifteenth-Century Journey

November 24th, 2020N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

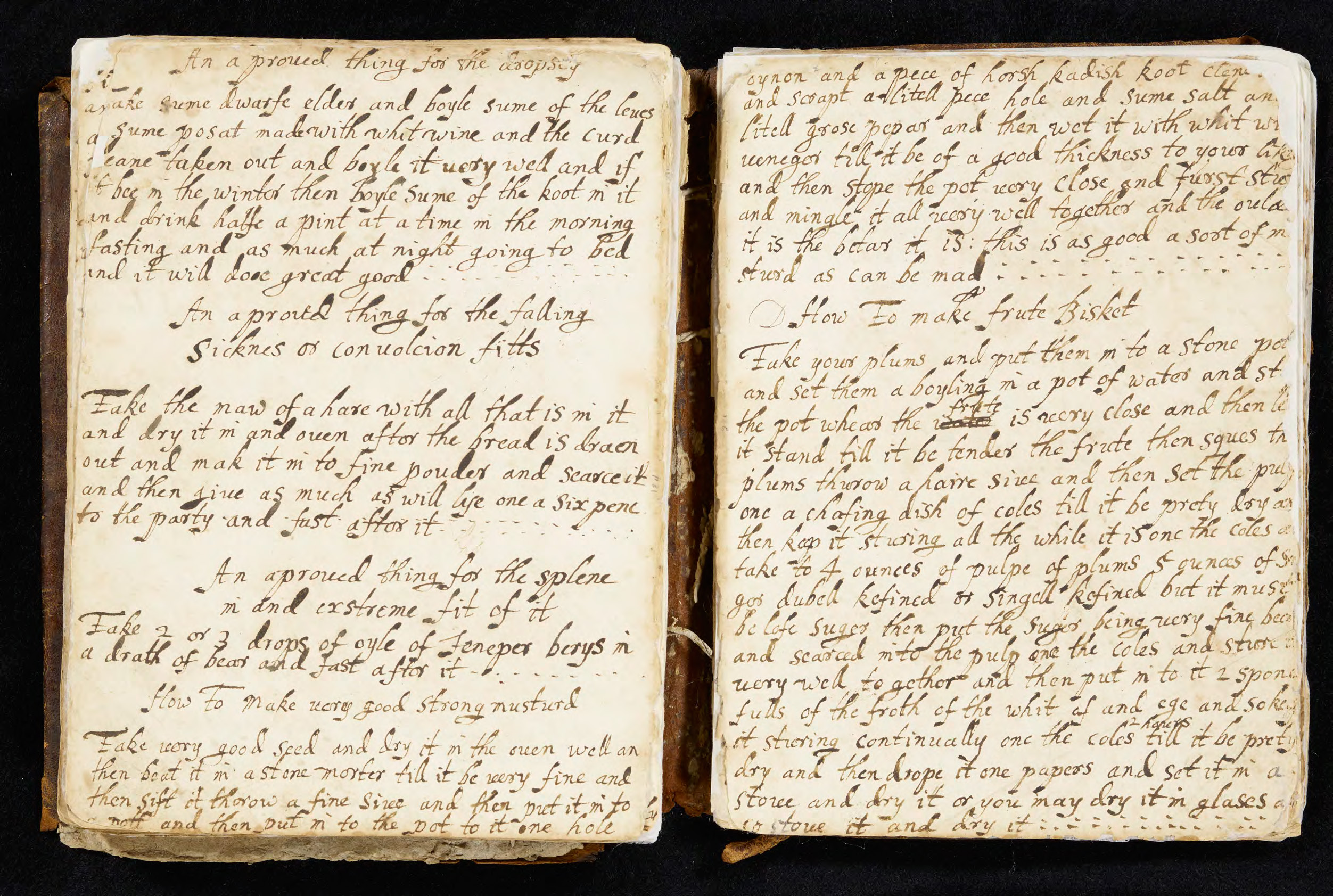

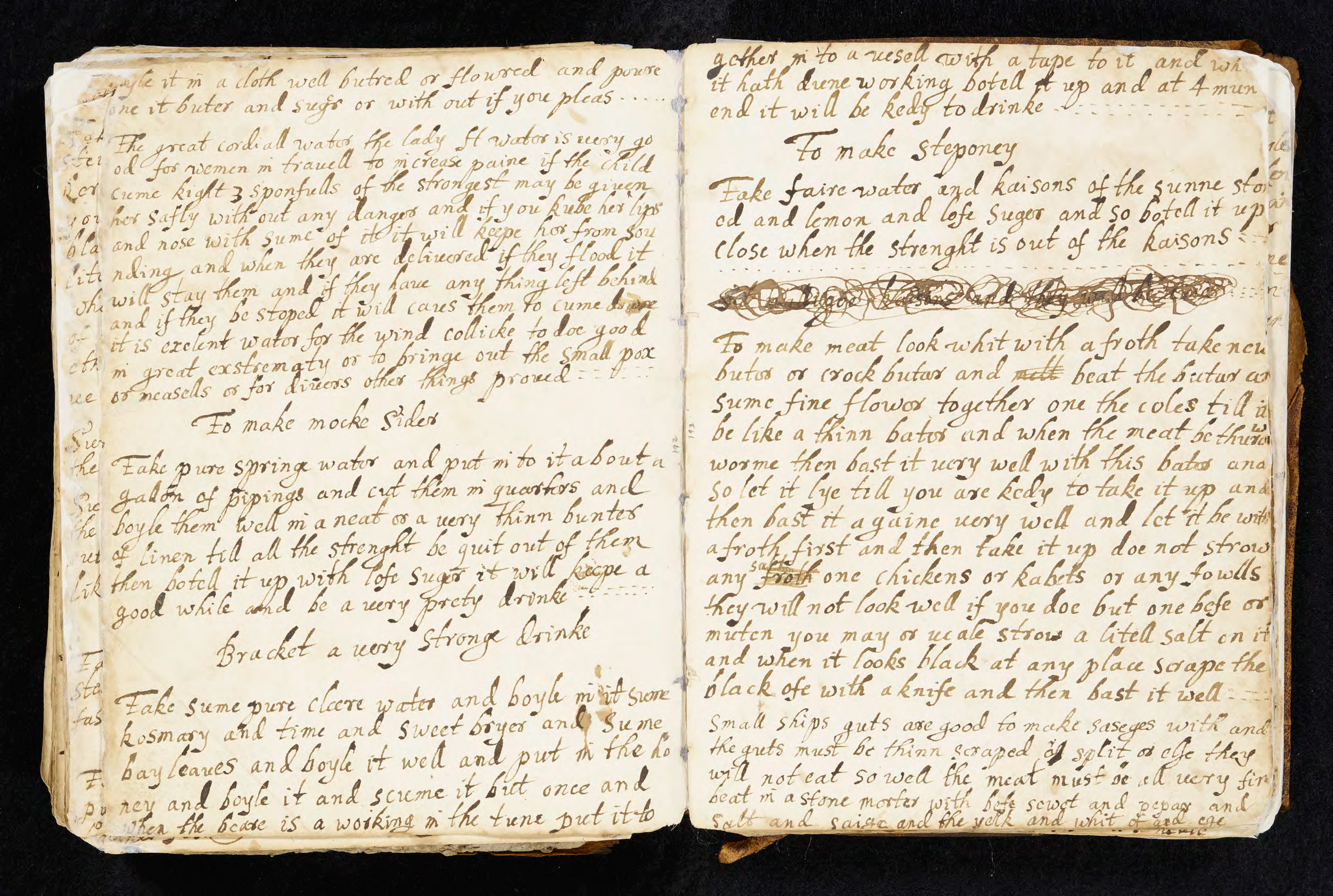

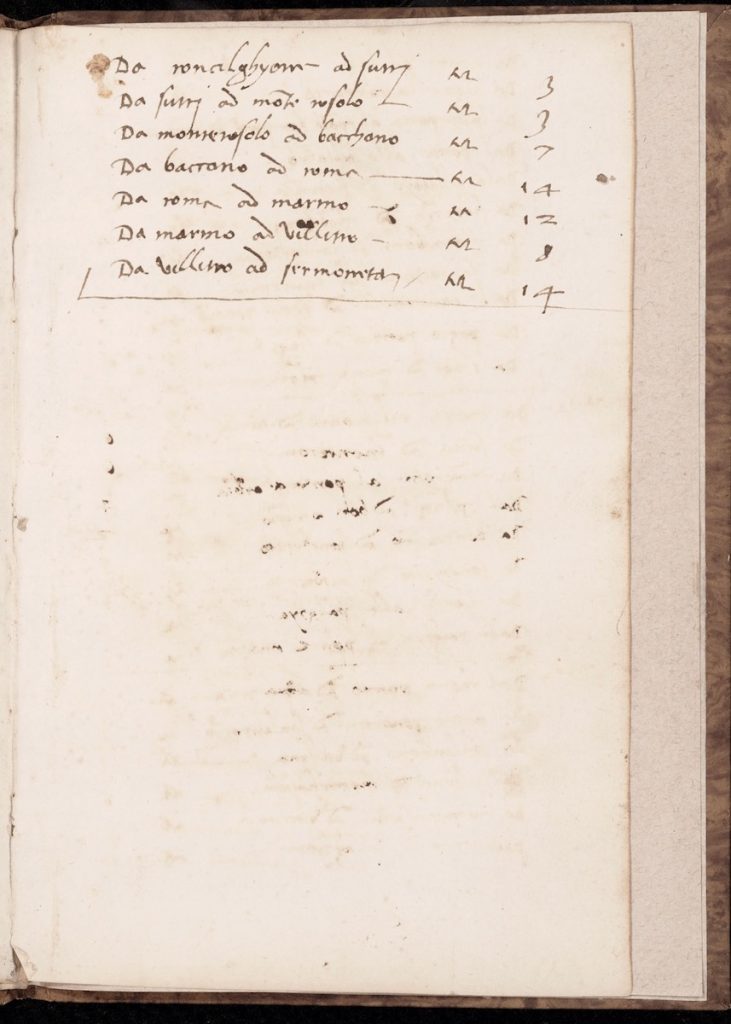

Written in Humanistic cursive by a single hand during the last decade of the fifteenth century, Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS B21 contains a travel itinerary from Italy to France and back. Currently consisting of only five folios, it was probably part of a larger book. It seems that each stop on the journey was recorded between February 1493, with a departure from Naples, Italy, and January 1494, with a return to Sermoneta, Italy, after going all the way to Paris, France. The majority of the text comprises the names of the cities, with occasional mentions of arrival or departure dates and a series of numbers in the margins that probably denote distances between the stops. Unfortunately, no personal name or a reason for the journey is mentioned, but from the language of the text and the style of handwriting we can surmise that the diary belonged to an Italian traveler.

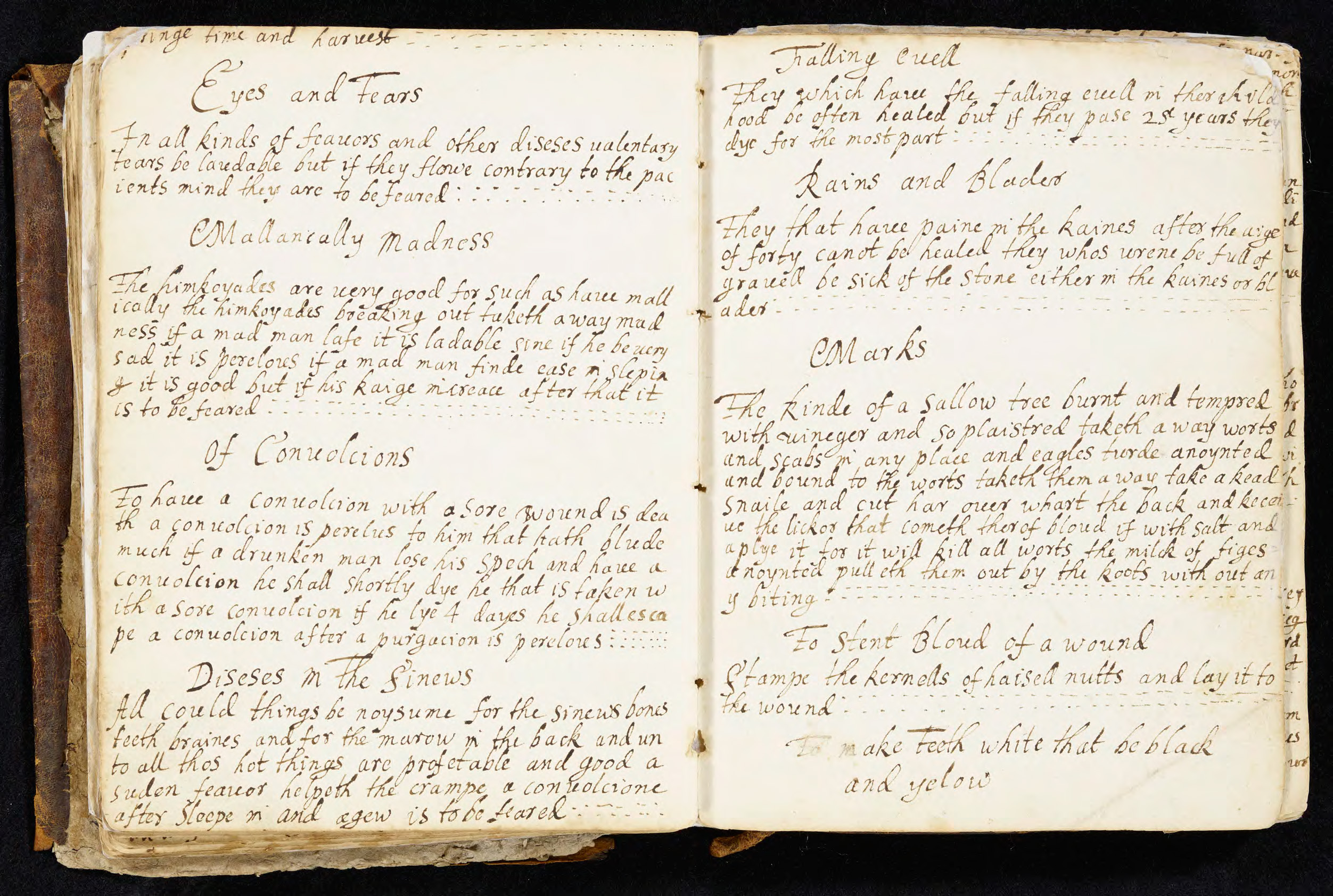

The journey begins on February 21, 1493, in Naples, Italy. 24 days later, on March 16, the traveler arrives at Marseille, France. There are thirteen stops noted for this first leg of the journey between Naples and Marseille. Most of them were relatively easy to identify:

Gayeta = Gaeta

Hostia = Ostia

Civita Vechya = Civitavecchia

Mo[n]te Arge[n]taro = Monte Argentario

Livorno = Livorno

Porto Vener[e] = Porto Venere

Ienoa = Genoa

Villa Francha = Villefranche-sur-Mer

Nirza = Nice

Santa Margarita = Île Sainte-Marguerite

Insola de Heres = Îles d’Hyères

I was not so sure about where “Poncio” is, which is mentioned as a stop between Gaeta and Ostia but I decided it must be Pontinia, which is located almost right in the middle of the two places. I also had my doubts about where “Cornito” might be. It is mentioned as a stop between Civitavecchia and Monte Argentario. Although there are other places with this name in both Benevento and Campania regions of Italy, the contemporary name of the place we are looking for in this stretch is probably Tarquinia, whose name has changed from Corneto to Tarquinia in the last century.

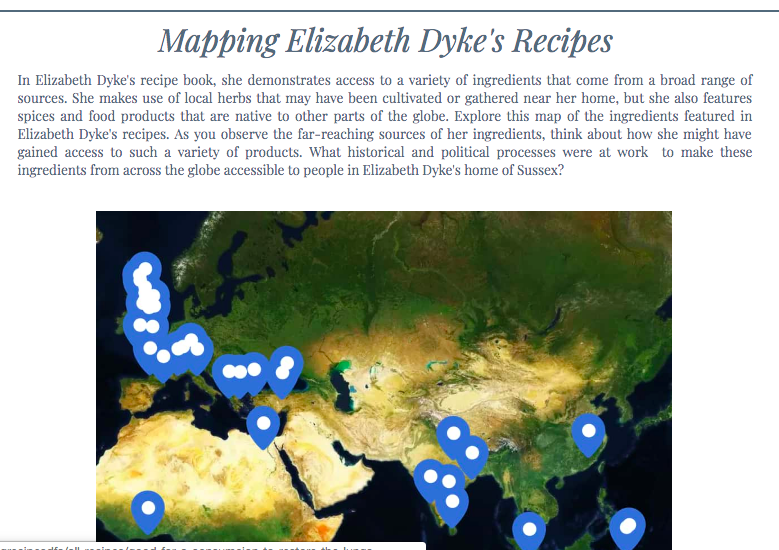

Map of Naples-Marseille itinerary in MS B21. Created using Tableau.

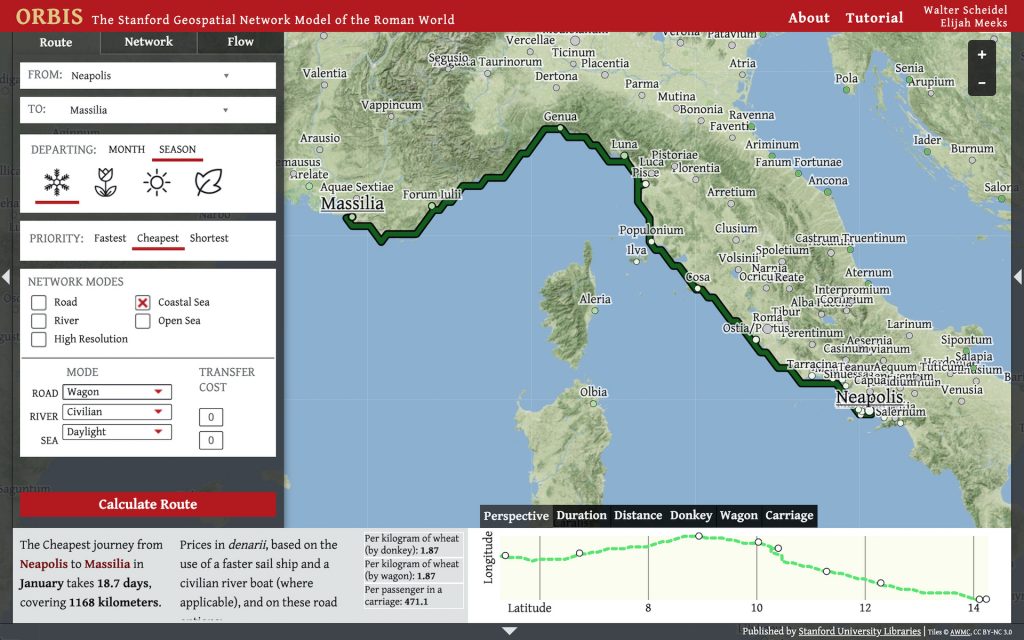

After I identified the stops for the first leg of this journey between Naples and Marseille, I decided to place them on a map and see how it looks: indeed, all the places lined up in a neat route along the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea and southern coast of France. What is striking is that all the places I was able to identify are on either the coast or an island close to the shore, such as Monte Argentario and Île Sainte-Marguerite. This gives us reason to think that this part of the journey was undertaken by ship along the coast of the Tyrrhenian and Ligurian Seas instead of by land. Now that we know the route, how long it took and the possible mode of travel, I was curious to compare this data. At that point, I turned to ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. Called by some “a Google Maps for Ancient Rome,” ORBIS allows one to analyze movements of people and goods along the principal routes of the ancient Roman world by taking into account different modes and means of transport and even the season in which the travel took place.

Since Roman travel networks and routes continued to be used during the Middle Ages, the approximations created in ORBIS would provide us a reliable comparison point. According to ORBIS, if one travels only by daylight the journey between Naples and Marseille on coastal sea takes 18.7 days during winter. Although by this route there seem to be fewer stops compared to what is recorded in MS B21, the major ports, such as Ostia and Genoa, remain unchanged. The traveler of MS B21 noted that they arrived at Marseille after 24 days. Given that there are more stops mentioned in the manuscript and that we do not know if they spent any considerable time in any of these places, 24 days seem reasonable.

According to MS B21, it seems that the anonymous traveler spent between April and August 1493 in Paris before going to Tours via Orléans and staying there until January the year after. The traveler began their return from Tours, France to Italy on January 23, 1494. On the way back, they traveled exclusively by land, passing through cities such as Turin, Milan, Parma, Bologna, Florence, and Rome. Instead of going back to Naples, where they started, however, they stopped at Sermoneta, approximately 100 miles north of Naples. Unfortunately, the date of arrival is not recorded in the manuscript. If the anonymous traveler of MS B21 was a member of a diplomatic legation, as suggested by Bernard Rosenthal, from whom the Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript, this was a tumultuous time and there would have been good reason for such a journey, for in this very year the Kingdom of Naples was under threat of invasion by Charles VIII, king of France.

If the anonymous traveler was on a mission to the French court, that would also explain their spending time not only in Paris but also in Tours. Palais des Tuileries was the Parisian residence of most French monarchs but Charles VIII and his court also spent considerable time in Tours and had a royal residence there, Château de Plessis-lèz-Tours. Furthermore, we know that the French king may have been traveling from Paris to Tours that very August as Queen Anne is recorded to have had a premature birth and that the baby was buried at Notre-Dame de Cléry, a place mentioned also in MS B21 as the next stop after Orléans on the way to Tours.

King Ferdinand I of Naples died only two days after the departure date mentioned in the manuscript, on January 25, 1494, after 35 years of reign. Although succeeded by his son Alfonso II, the death of Ferdinand I allowed Charles VIII to lay claim to the throne and invade the Kingdom of Naples later in 1494. This marked the beginning of the Italian Wars, also known as Habsburg-Valois Wars, which took place between 1494 and 1559, during which the Kingdom of Naples was the focus of dispute among different dynasties and constantly changed hands.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Bernard M. Rosenthal Inc. in July 1960, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.