“My Dear Mother”: Letters by William Clarke Quantrill

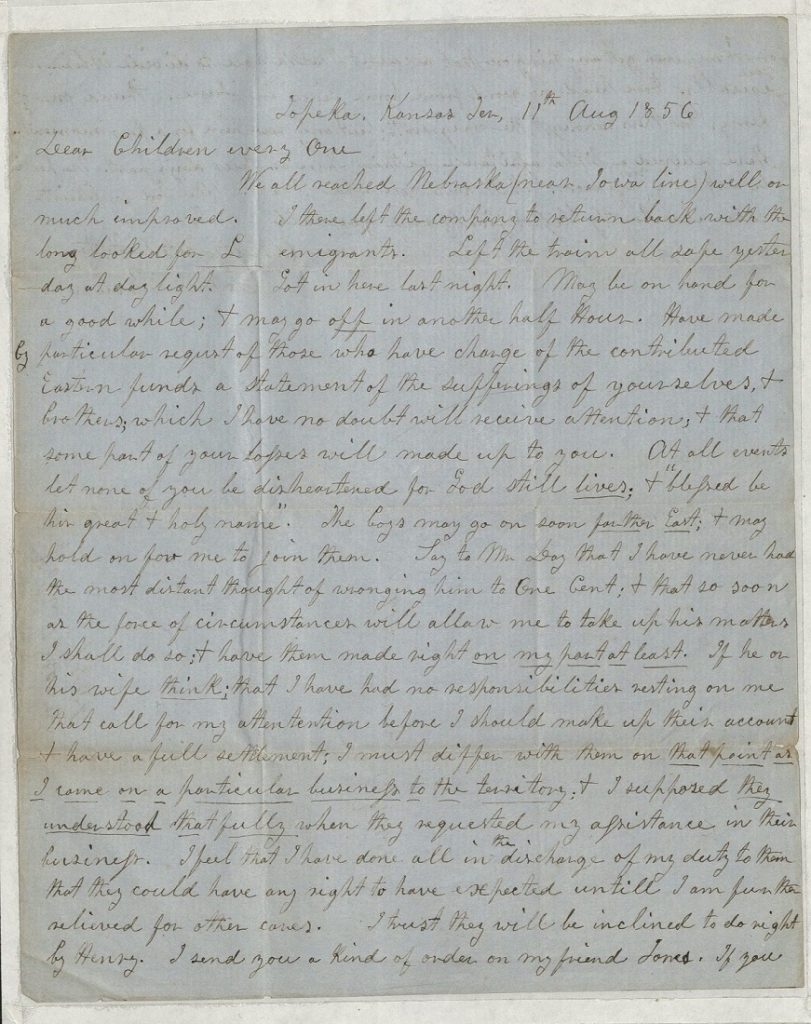

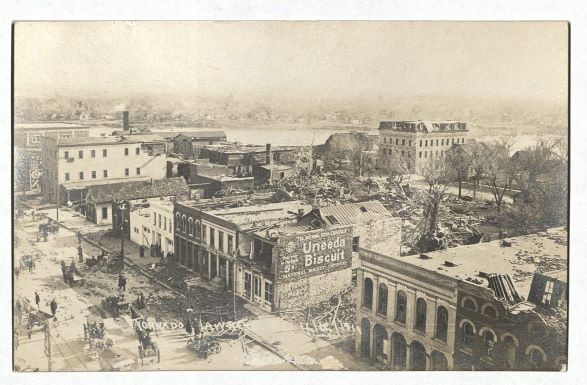

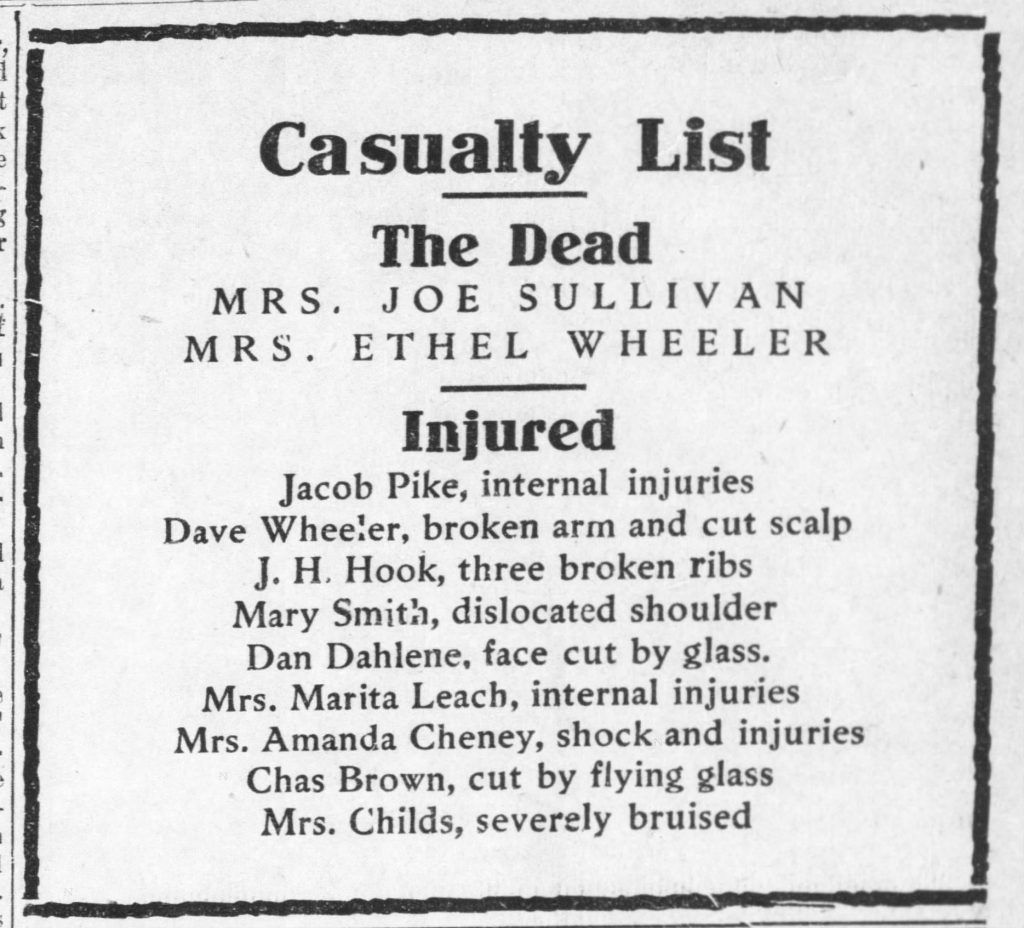

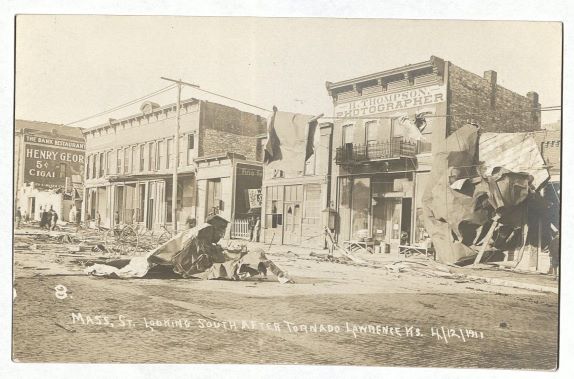

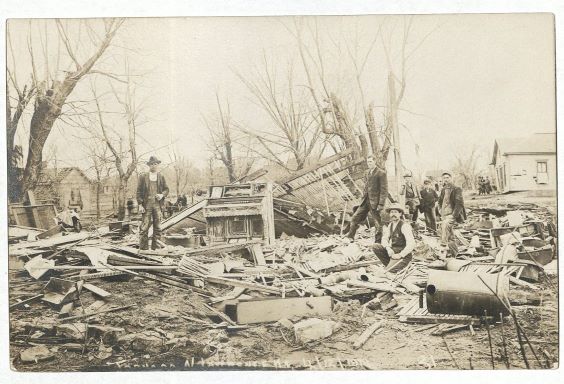

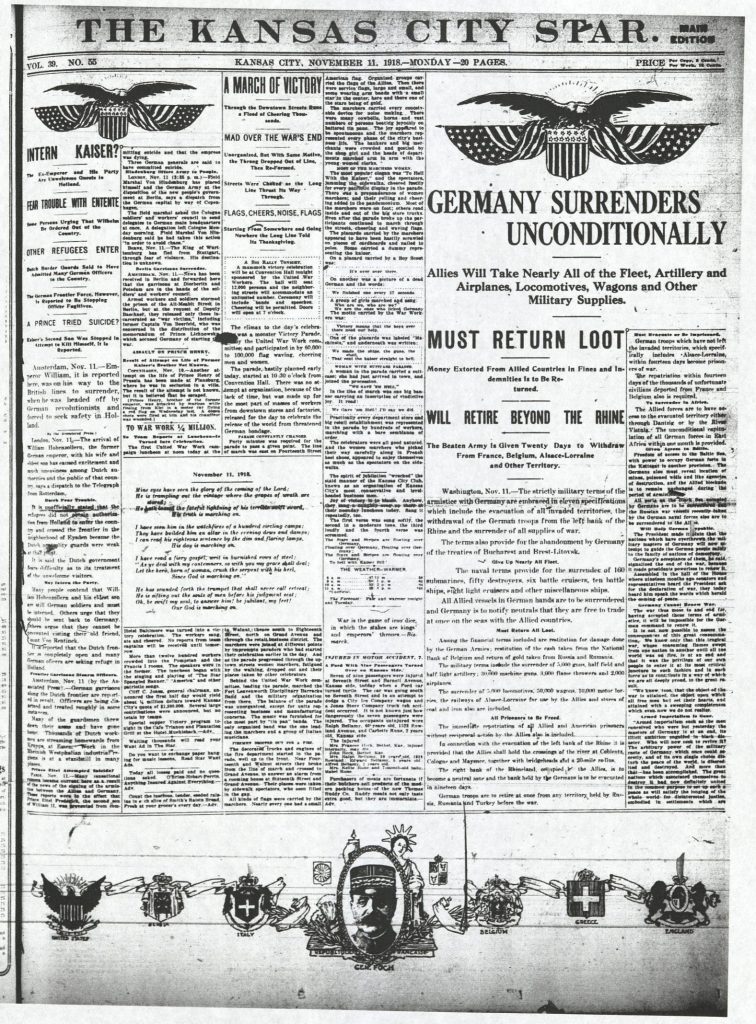

August 20th, 2019One of the most renowned collections in Spencer Research Library is a series of letters written by William Clarke Quantrill to his mother, Caroline Cornelia Clarke Quantrill, between 1855 and 1860. During this period, Quantrill wrote sporadically to Caroline, letting her know his whereabouts, describing his plans for the future, promising he would come home soon, and vowing to send money when he could. Quantrill rarely revealed his views on politics or current events in these letters, and nothing in them hints at the course he would choose after he stopped writing home altogether. On August 21, 1863, 156 years ago this week, Quantrill gained infamy for organizing and leading a guerrilla raid on Lawrence in support of the Confederate cause.

Quantrill was born in Dover, Ohio, on July 31, 1837. After graduating from high school at age sixteen, he began teaching school in Dover, a career he would return to off and on several times. His father passed away in 1854, leaving Quantrill, as the eldest of eight children, the male head of the family. Caroline took in boarders, and his oldest sister took in sewing jobs, but the family remained very poor.

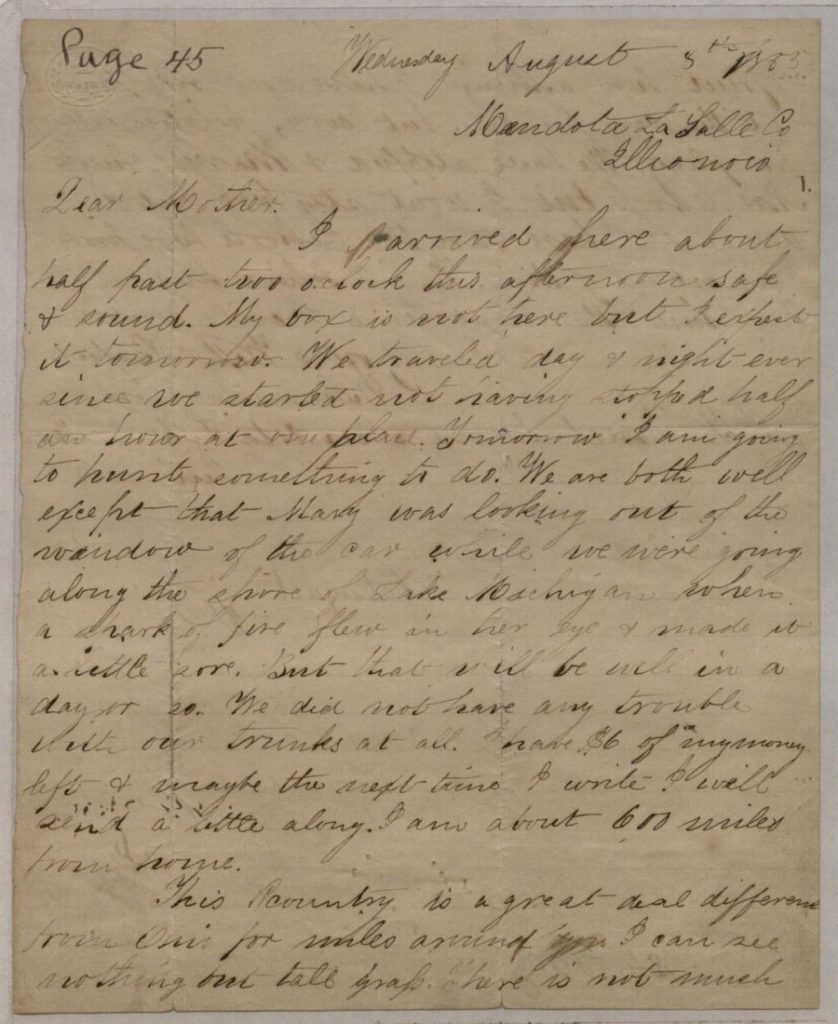

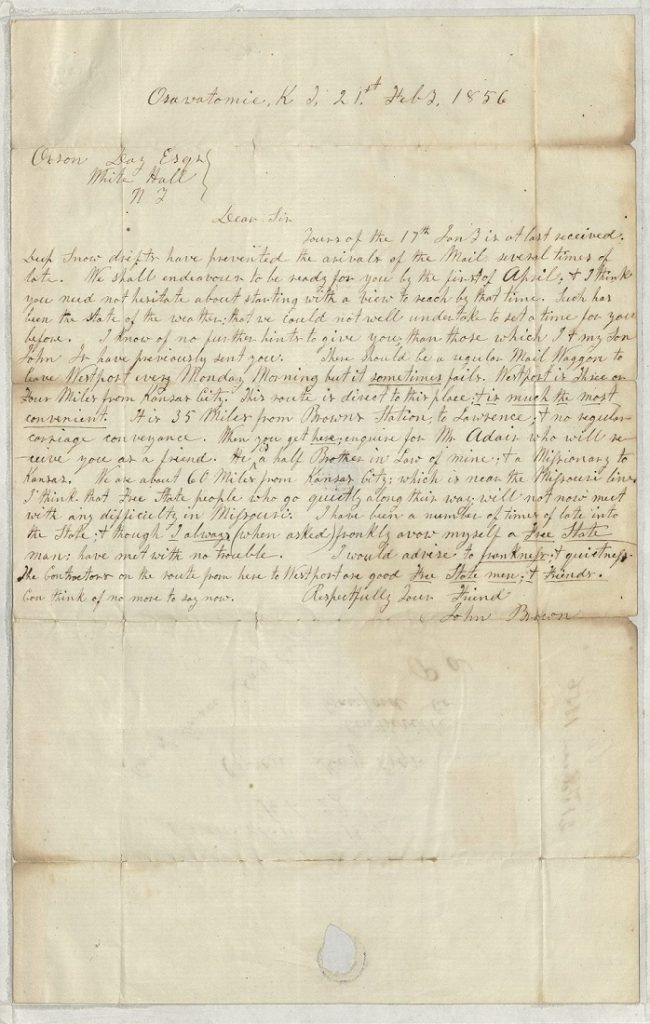

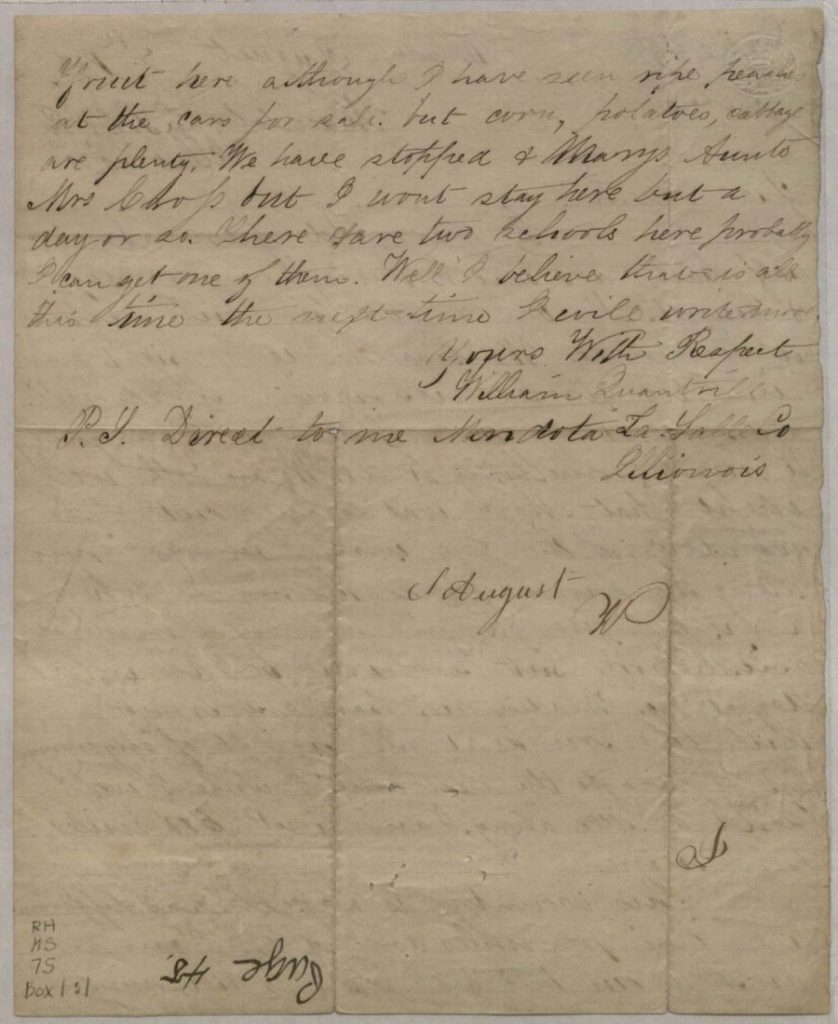

In the summer of 1855, Quantrill joined a group of other Dover residents and traveled to Illinois to seek better farmland and to see what other opportunities may lie a little farther west. In the letter below, dated August 8, 1855, he tells Caroline of his safe arrival, indicates he will try to send her some money, and mentions the possibility of getting a teaching position. “This country is a great deal different from Ohio,” he writes, “for miles around I can see nothing but tall grass.”

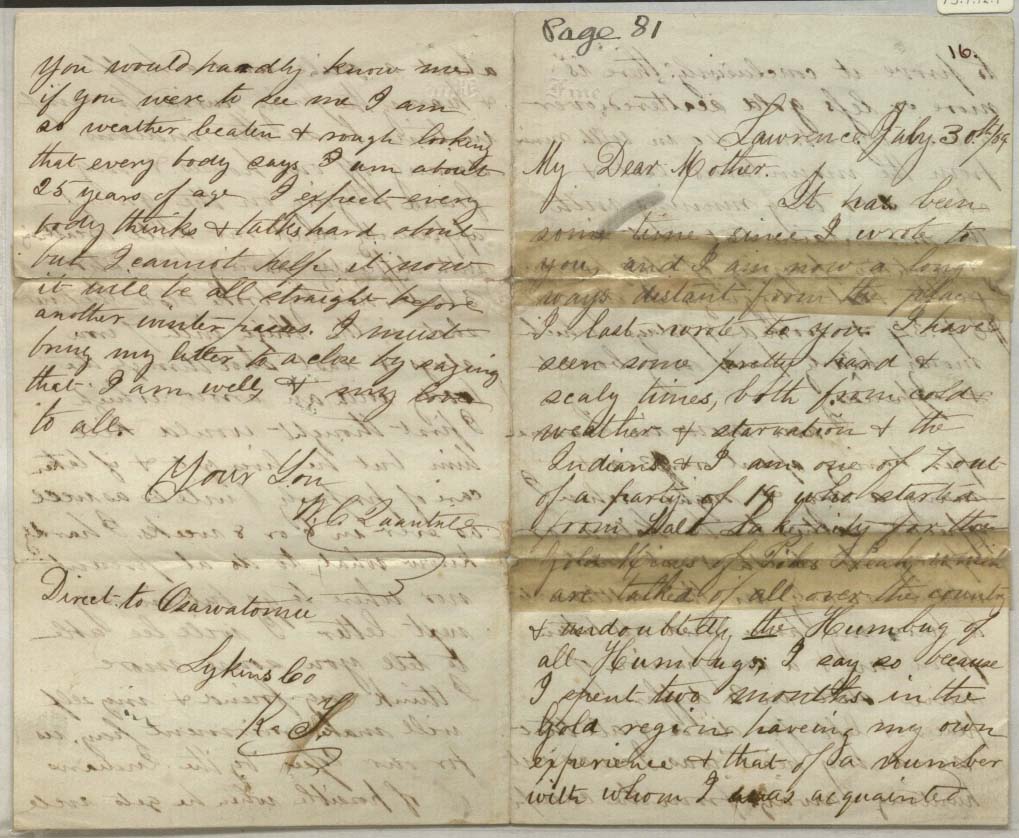

By July 1859, Quantrill had tried his luck at various occupations, in addition to teaching, and had explored business enterprises in Mendota, Illinois; Fort Wayne, Indiana; and the Kansas and Utah Territories. He had even tried his luck in the gold mines of Colorado. He was restless, and nothing seems to have satisfied him. The letter below, written to Caroline on July 30, 1859, was from Lawrence, Kansas, the place where he would gain his notoriety. In it, he relates a story to his mother that must have stirred her worst fears for her son’s safety.

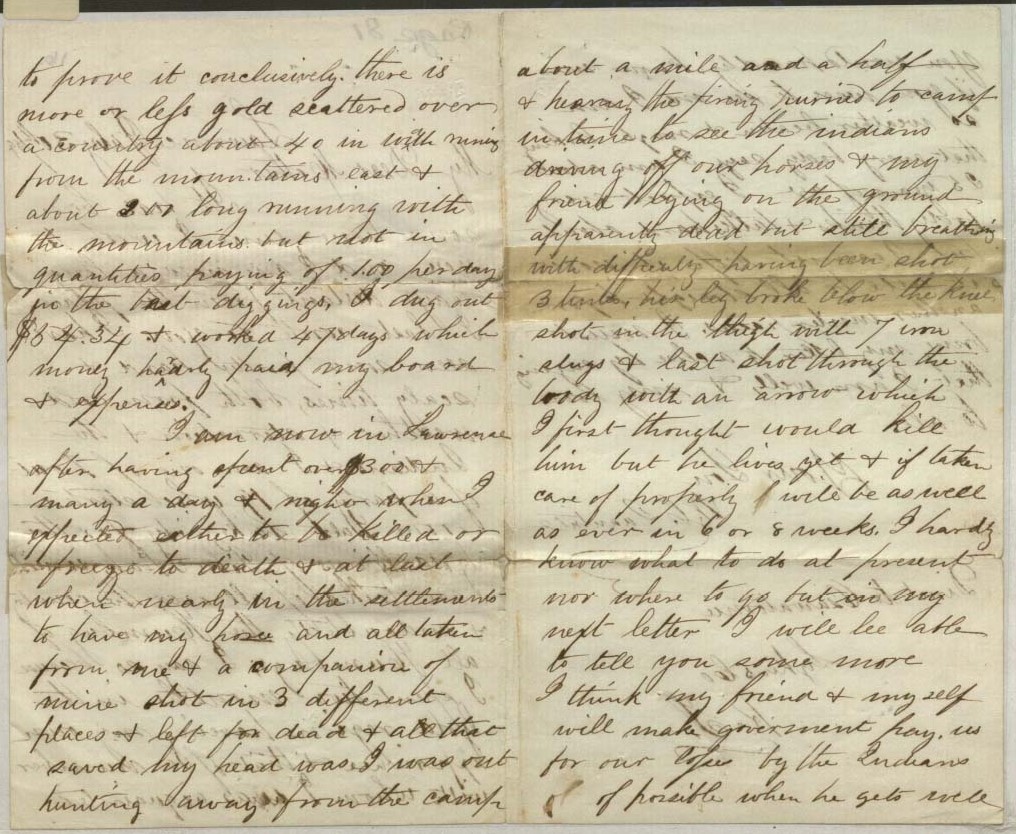

It has been some time since I wrote to you, and I am now a long ways distant from the place I last wrote to you. I have seen some pretty hard & scaly times, both from cold weather & starvation & the Indians & I am one of 7 out of a party of 19 who started from Salt Lake City for the Gold Mines of Pikes Peak which are talked of all over the country & undoubtedly the Humbug of all Humbugs. I say so because I spent two months in the gold region haveing [sic] my own experience & that of a number with whom I was acquainted to prove it conclusively…

I am now in Lawrence after having spent over $300 & many a day & night when I expected either to be killed or freeze to death & at last when nearly in the settlements to have my horse and all taken from me & a companion of mine shot in 3 different places & left for dead & all that saved my head was I was out hunting away from the camp about a mile and a half & hearing the firing hurried to camp in time to see the indians driving off our horses & my friend lying on the ground apparently dead but still breathing with difficulty having been shot 3 times, his leg broke below the knee, shot in the thigh with 7 iron slugs & last shot through the body with an arrow which I first thought would kill him but he lives yet & if taken care of properly will be as well as ever in 6 or 8 weeks. I hardly know what to do at present nor where to go but in my next letter I will be able to tell you some more. I think my friend & myself will make goverment pay us for our losses by the Indians if possible when he gets well.

You would hardly know me if you were to see me I am so weather beaten & rough looking that every body says I am about 25 years of age.

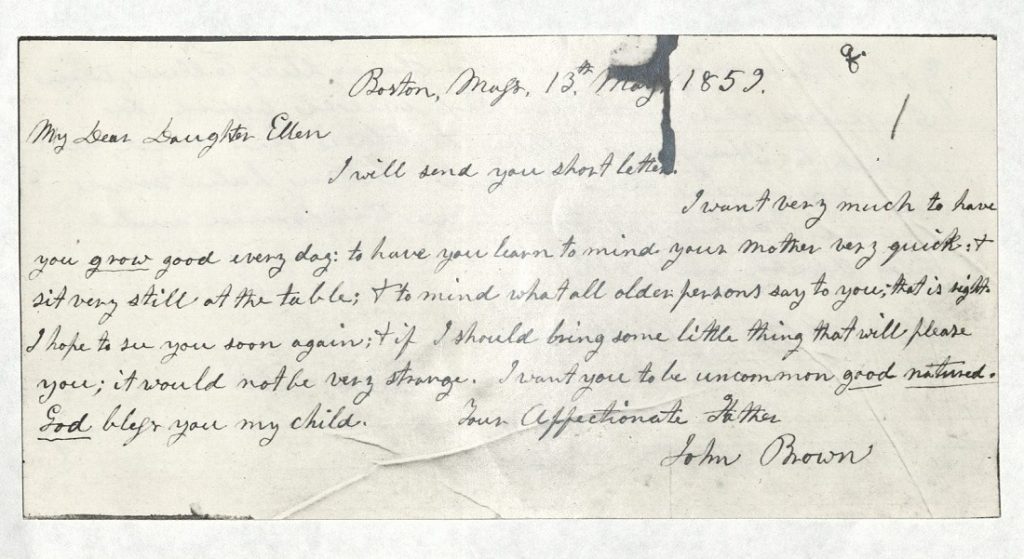

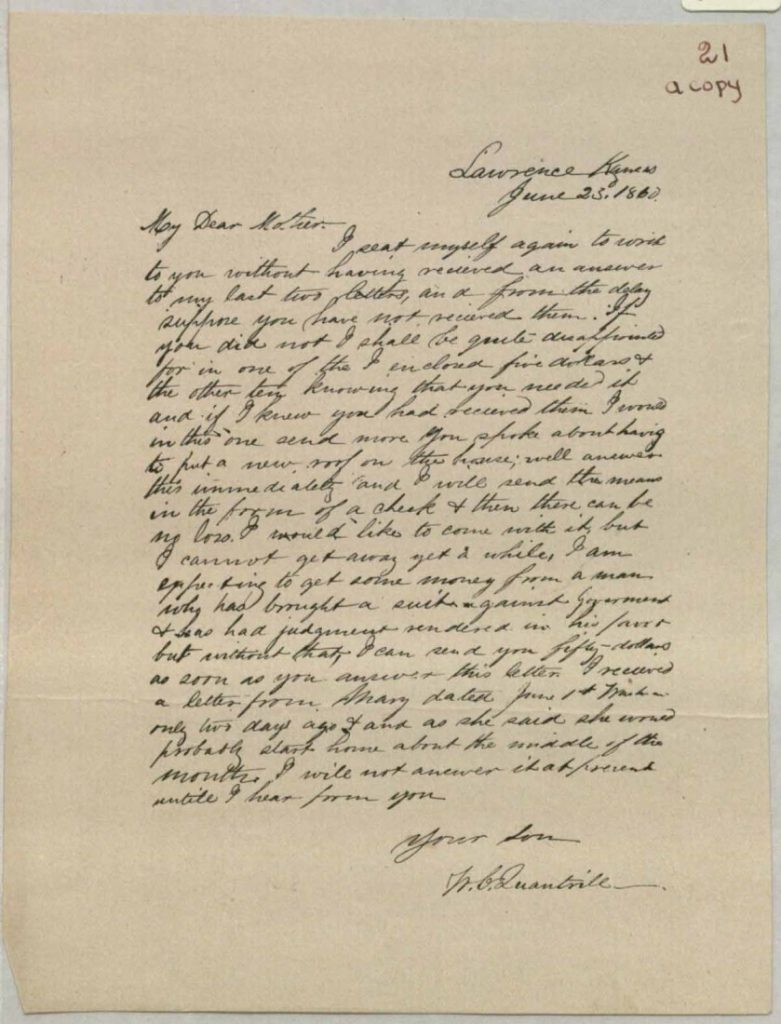

In his final letter to Caroline, written on June 23, 1860, Quantrill inquires about the money he says he sent to her, tells her he will send more when he can and talks about the weather and his health. H also speaks of wanting to visit, but says he cannot get away. After this letter, Caroline would contend that she had no more word from him, relying on rumors and reports that she heard from the newspapers, her neighbors, and strangers to try to know his whereabouts.

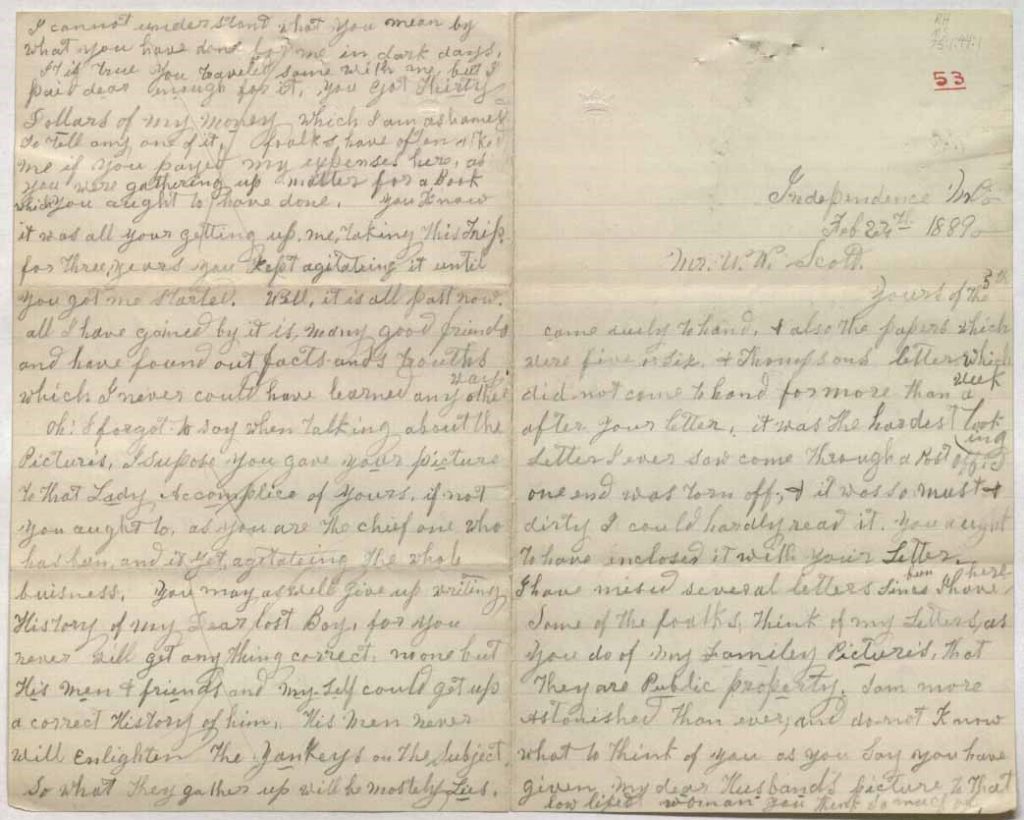

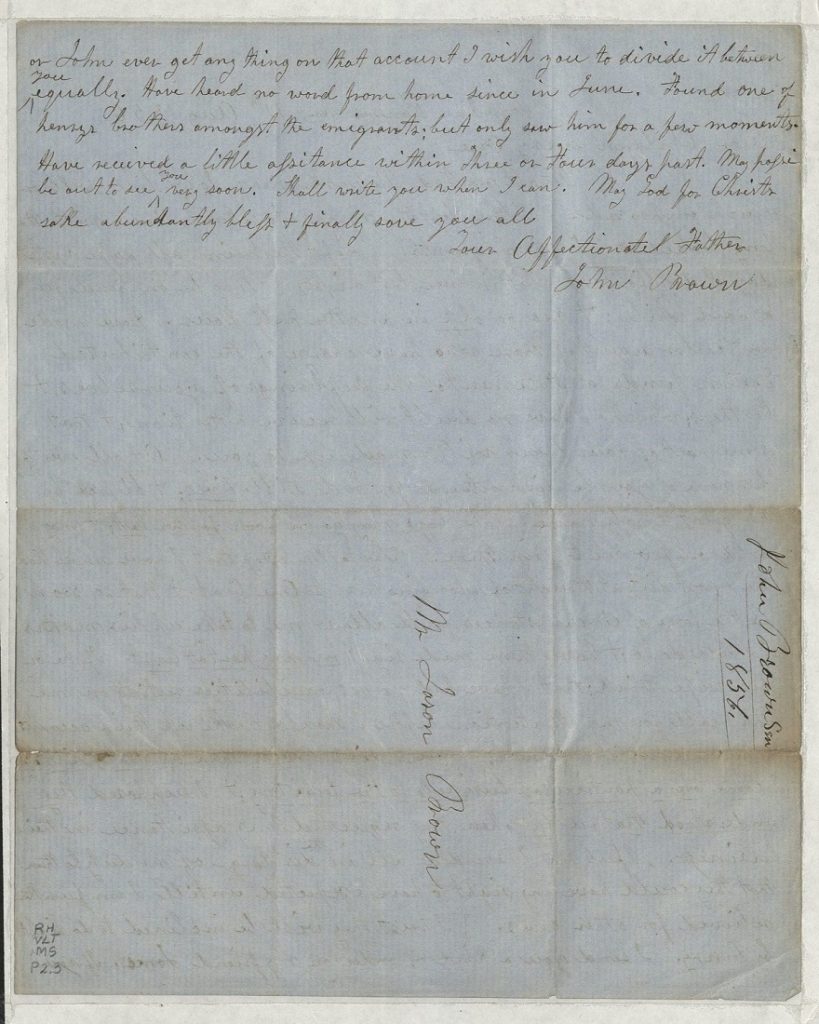

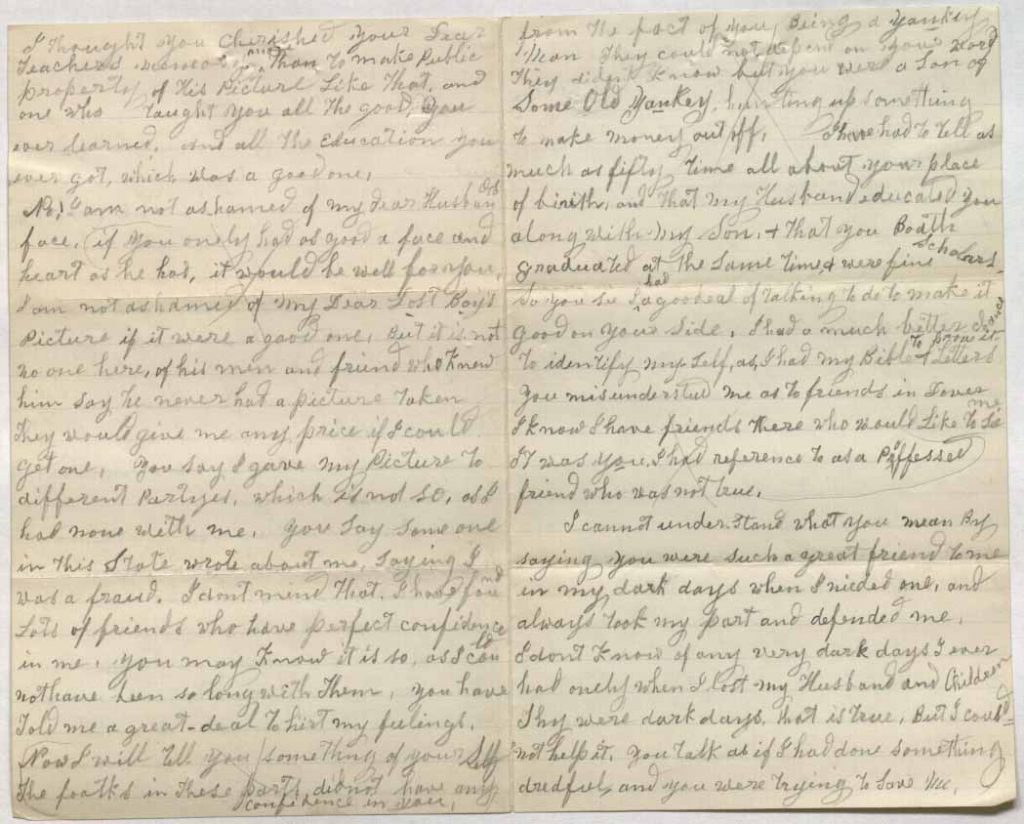

Caroline loved her son and found many of the stories about him quite hard to accept or even untrue. Caroline wrote the letter below on February 24, 1889, to the childhood friend of her son, William W. Scott. In it, she rails against Scott for what she perceives as his attempt to vilify and profit from her son. “You have told me a great-deal to hirt [sic] my feelings,” she tells him. Scott had become like a son to Caroline and often provided for her. He also wanted to write a book about Quantrill, but out of respect to Caroline, he was waiting until her death to do it. When she found out about the book, she turned on him, writing

Now I will tell you some thing of your Self The foalks in these parts did not have any confidence in you from the fact of you Being a Yankey Man They could not depend on your word They didnt know but you were a Son of Some Old Yankey. hunting up something to make money out off. I have had to tell as much as fifty time all about your place of birth, and that my Husband educated you along with My Son. & that you Boath graduated at the same time, & were fine scholars. So you see I had a goodeal [good deal] of talking to do to make it good on your side…

You may as well give up writing a History of my Dear lost Boy, for you never will get any thing correct. no one but His men & friends and my-self could get up a correct History of him. His men never will Enlighten the Yankeys on the Subject. So what they gather up will be mostely Lies.

Caroline defended her son until her death in 1903.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services

Sources:

William Clarke Quantrill Correspondence. RH MS 75. Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries.

Leslie, Edward E. The Devil Knows How to Ride. New York: Random House, 1996.