Political Junkie?

November 3rd, 2020Today is Election Day, so in the spirit of voting and civic engagement, we’re featuring a collection full to the brim with politicians.

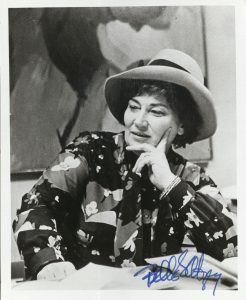

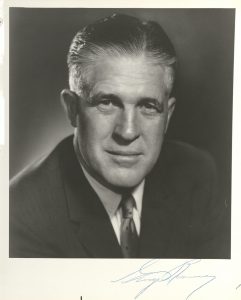

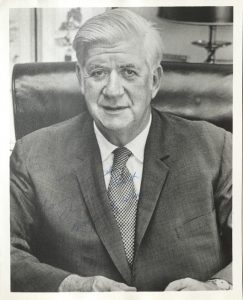

Wayne Davis taught history and was a high school principal in Cherryvale, KS, before joining, in 1972, the History faculty at what is now Highland Community College. In addition to his busy day job, he maintained a side passion: collecting signed photographs of US politicians and federal officials. His collection at Spencer Research Library (MS 189) consists of autographed pictures and brief letters from close to 260 public figures, collected between the late 1940s and the 1970s. Included are politicians like New York Member of Congress Bella Abzug (1920-1988), a feminist and civil rights advocate reintroduced to a new generation through the 2020 TV series, Mrs. America; Michigan Governor George Romney (1907-1995), who in 1968 ran for the Republican party nomination that Richard Nixon would eventually secure; and Massachusetts Member of Congress Thomas P. (Tip) O’Neill, Jr. (1912-1994), who also served as Speaker of the House from January 1977 to January 1987.

Bella Abzug, Representative for New York ; George Romney, Michigan Governor; and Thomas P. (Tip) O’Neill, Representative for Massachusetts. Wayne Davis Collection. Call #: MS 189, Box 1, Folder: Abzug, Box2, Folder: Romney and Folder: O’Neill . Please click images to enlarge. Bonus points to anyone who can read the faint blue ink of O’Neill’s inscription.

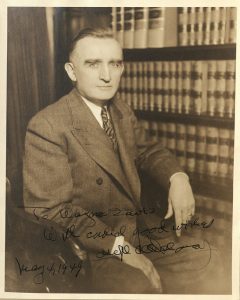

Davis would often annotate the back of the signed photographs with notes about the politician’s date of birth, political party, religion, and career, as seen on the signed photograph of Wyoming Senator Joseph C. O’Mahoney (1884-1962).

“With cordial good wishes”: Inscribed photograph of Wyoming Senator, Joseph C. O’Mahoney, with Davis’s notes on O’Mahoney and his career. Wayne Davis Collection. Call #: MS 189, Box 2, Folder: O’Mahoney. Click images to enlarge.

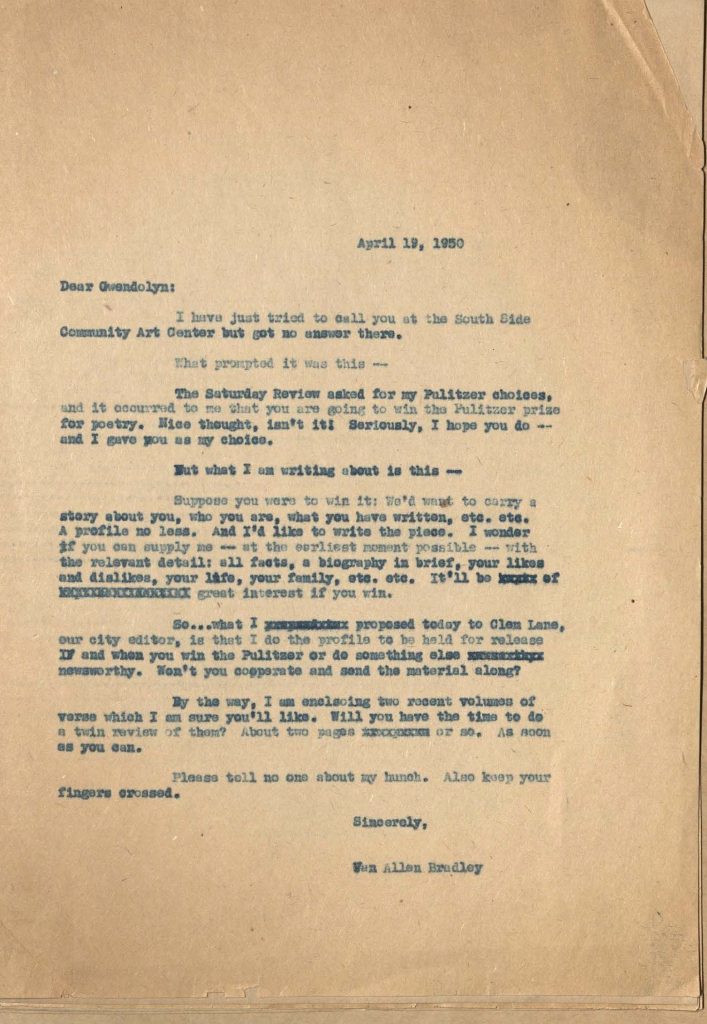

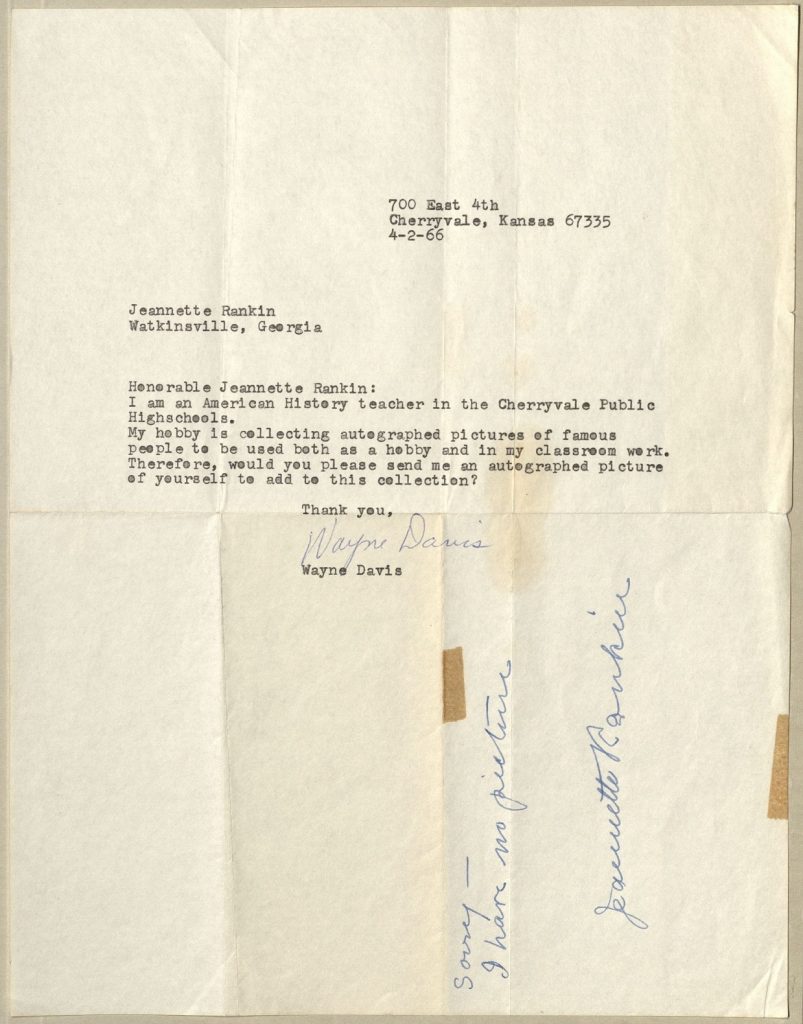

Davis appears to have collected the majority of these by simply writing to the figure in question. “My hobby is collecting autographed pictures of famous people,” he explained in a 1966 letter to former Montana Representative, Jeanette Rankin (1880-1973), “to be used both as a hobby and in my classroom work.” As a suffragist and the first woman elected to Congress (winning a House seat in 1916, and then again in 1940), Rankin would certainly have been a “get” for Davis’s collection. However, in this particular instance, he would have to be satisfied with just an autograph. “Sorry— I have no picture,” Rankin jots in reply along the side of his letter (below), before signing her name. Although Rankin was 85 at the time Davis sent his request, she wasn’t entirely retired from politics. In fact, in 1968, she would lead the “Jeanette Rankin Brigade,” a march of women’s groups on Washington, DC to protest the Vietnam War. A committed pacifist, Rankin was the only member of Congress to vote against US participation in both World War I and World War II. Though Davis did not succeed with Rankin, his collection is a testament that many other politicians obliged his requests.

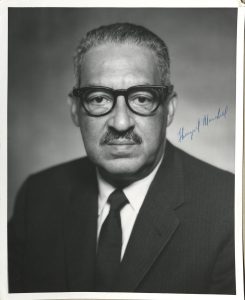

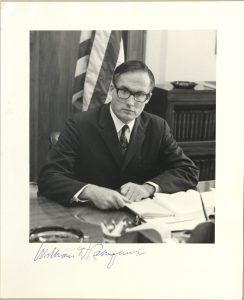

Davis also collected signed photographs for federal officials, and to a much smaller extent foreign dignitaries, heads of state, and public figures such as astronauts and entertainers. Supreme Court Justices Thurgood Marshall (1908-1993) and William H. Rehnquist (1924-2005) are both represented in the collection. Marshall’s signed photograph is accompanied by a brief note on his letterhead as Solicitor General of the United States. Dated June 27, 1967, it was sent to Davis shortly after his nomination to the Supreme Court (on June 13, 1967) but before his confirmation (on August 30, 1967).

Supreme Court Justices: Thurgood Marshall and William H. Rehnquist. Wayne Davis Collection. Call #: MS 189, Box 2, Folders Marshall and Rehnquist. Click images to enlarge.

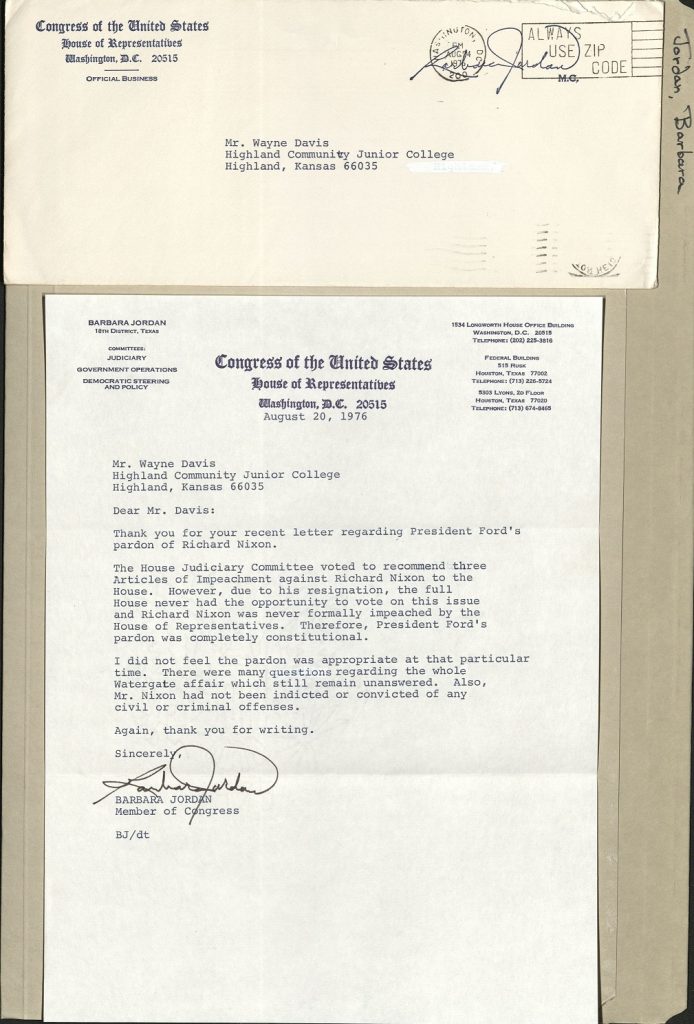

In the later years of his collecting, Davis also sent queries to several politicians, seeking their opinions on the “Mayaguez Incident” and President Ford’s 1974 pardon of Richard Nixon. Among those to respond on the issue of the pardon were Texas Representative Barbara Jordan (1936-1996) and Kansas Representative and Senator Robert J. Dole (1923- ). Replying in February 1977, Dole (or an aide replying in his stead), wrote: “… I must say that at the time of the pardon, I was very distressed by the action taken by President Ford. Although in retrospect, I now feel that it was necessary to put Watergate and all of its ramifications behind us so that the nation could move forward.” He continued that he felt that Ford’s “controversial decision had an adverse effect on his chances in the recent campaign,” alluding to Ford’s loss to Jimmy Carter in the 1976 presidential election.

A lawyer by training, Representative Barbara Jordan served on the U.S. House Judiciary Committee as it considered articles of impeachment. Her speech at the opening of the committee’s hearing is praised as one of the finest examples of American political oratory (you can read and watch it here). Though the committee approved articles of impeachment, Nixon resigned before the process advanced further in the House and the Senate. It is that unfinished process and a lawyer’s eye for legal detail that shapes Jordan’s reply to Davis. “I did not feel the pardon was appropriate at that particular time,” she (or her aide) explained, “There were many questions regarding the whole Watergate affair which remain unanswered. Also, Mr. Nixon had not been indicted or convicted of any civil or criminal offenses.” Jordan’s reply to Davis, sent in August of 1976, came at a landmark moment. in her career. A month earlier, she had made history as both the first woman and the first African American to give the keynote address at a Democratic National Convention

Wayne Davis’s collection offers a photo-friendly and slightly idiosyncratic glimpse into American politics, but it is just one of many potential points of entry for researchers. Spencer Library, for example, holds the papers of a number of Kansas politicians, from former Governors Robert Blackwell Docking and Robert F. Bennett, to former US Congresswoman Jan Meyers, to former Kansas State Senate and House Representative Billy Q. McCray, to name but a few. And Spencer Library’s Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements is one of the largest collections of US left and right wing literature in the country.

We invite you to explore politics across our collections and—most importantly—to engage by casting your vote! Polls are open in Kansas until 7 p.m. today.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian