Irish Manuscripts for Beyond 2022

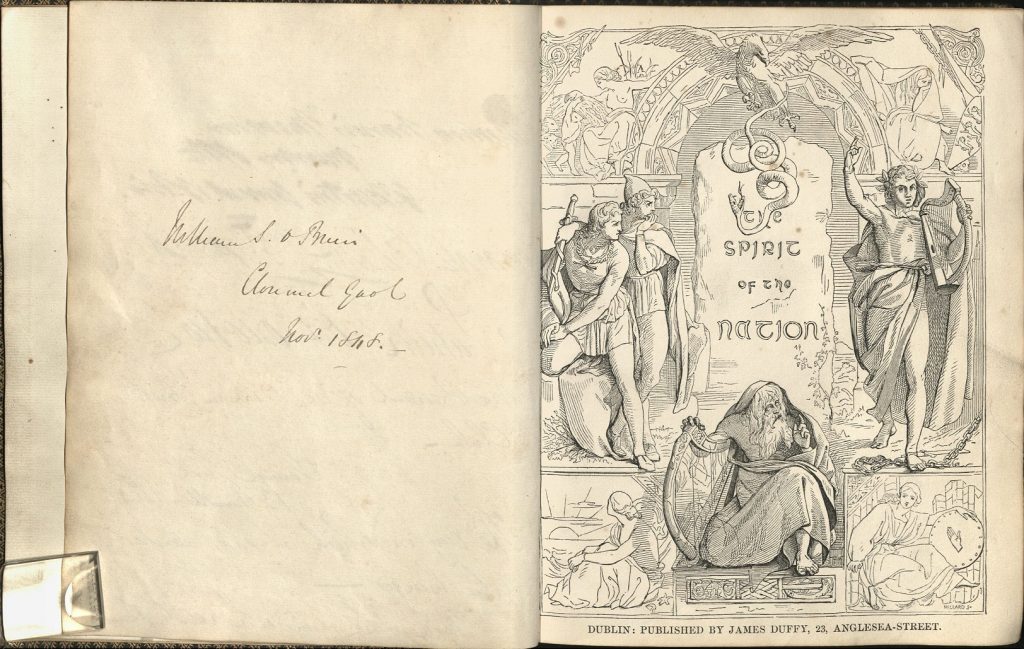

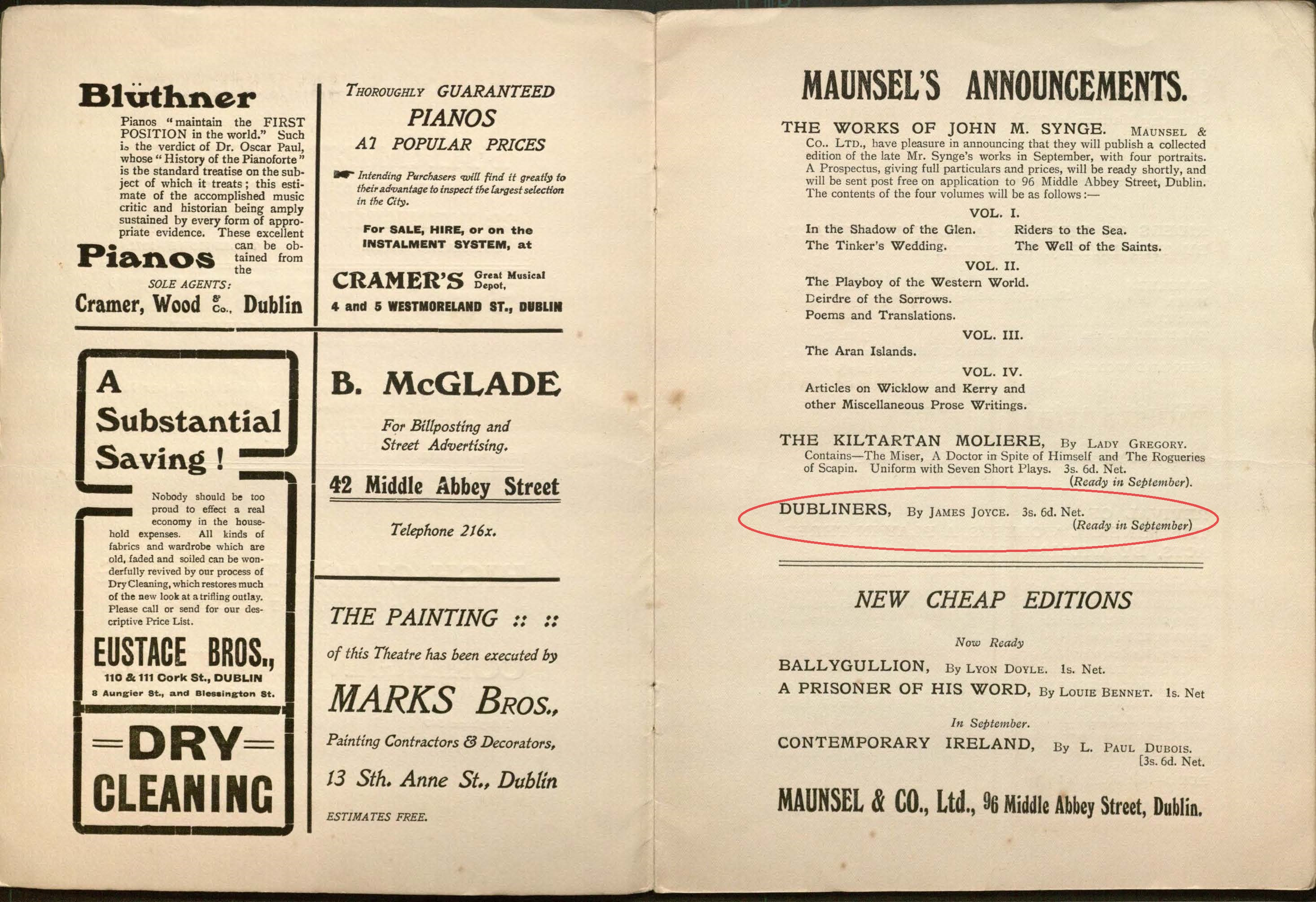

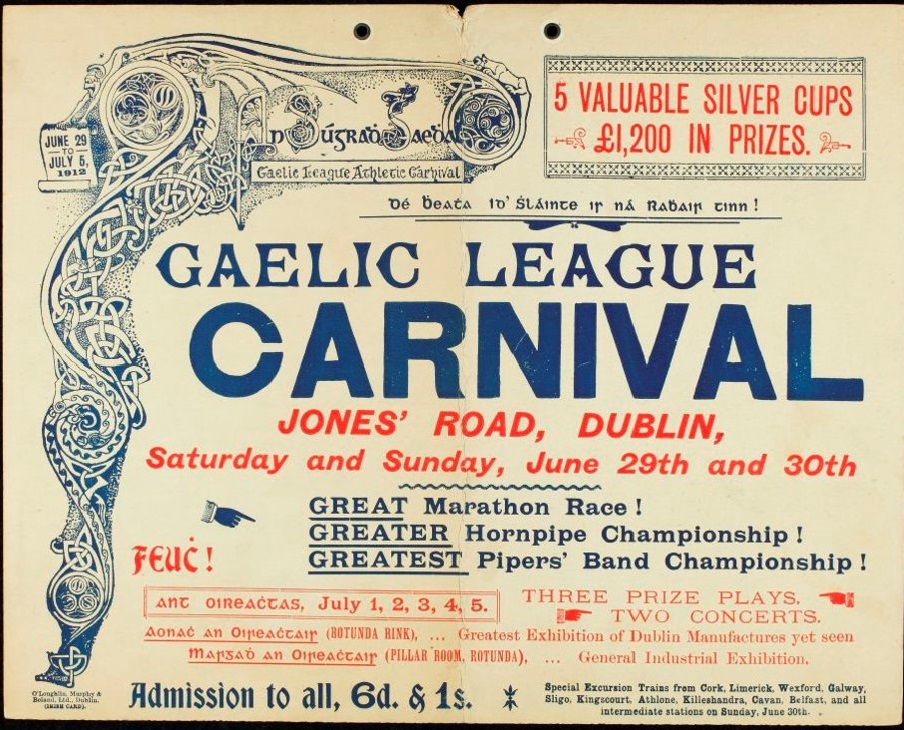

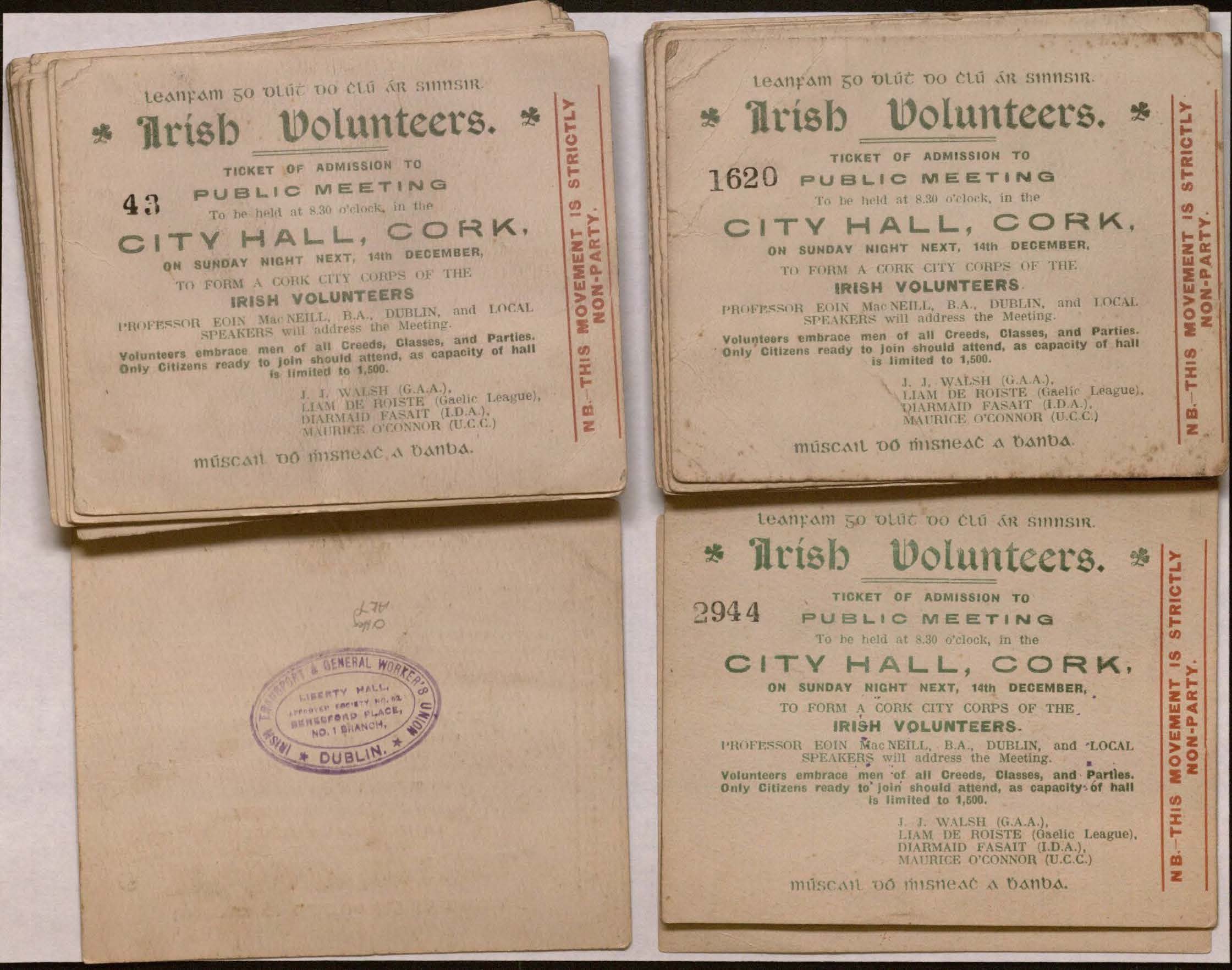

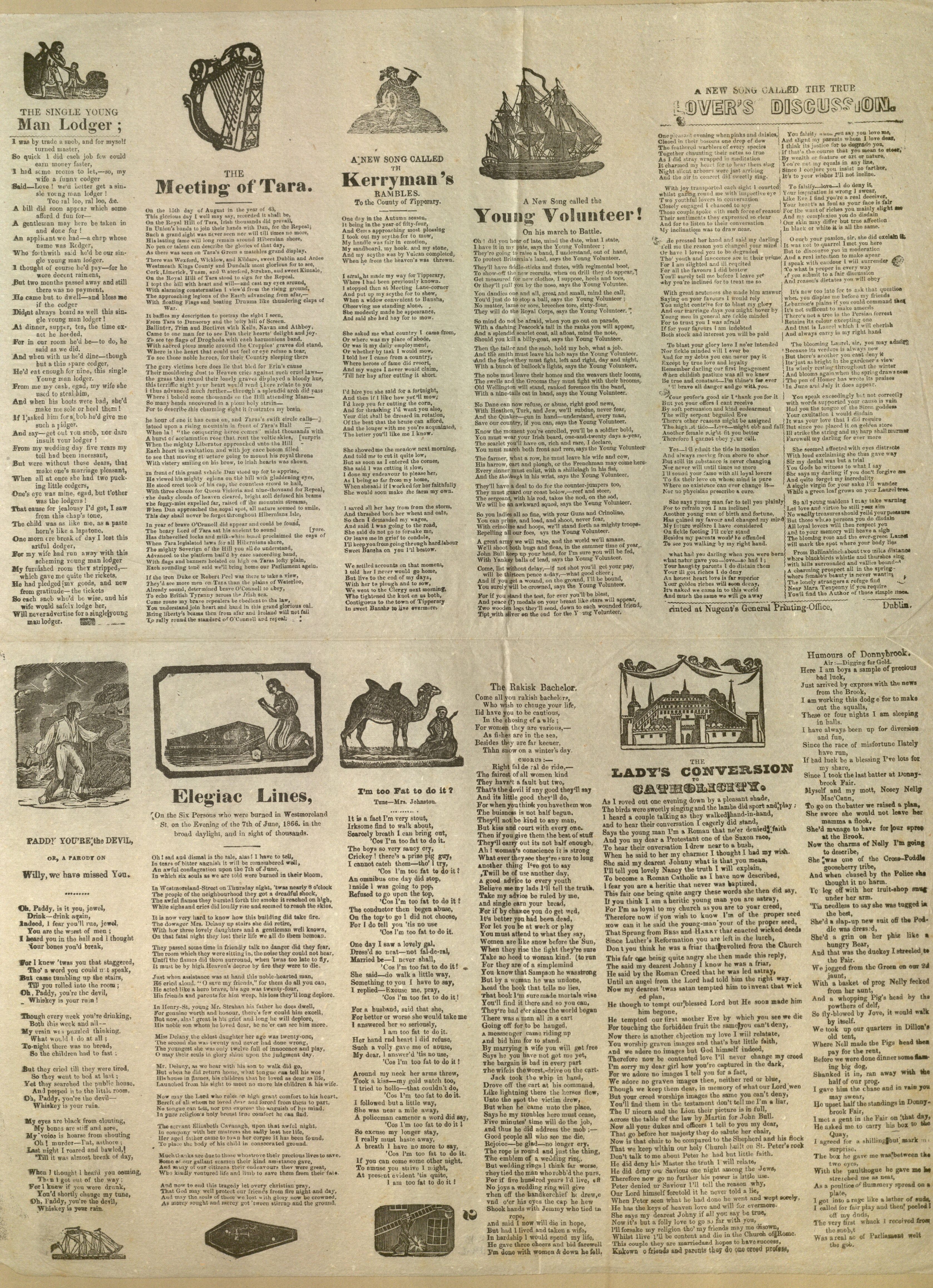

March 17th, 2021In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, this week we are highlighting KU’s participation in Beyond 2022: Ireland’s Virtual Record Treasury. On June 30, 1922, in the midst of the Irish Civil War, the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) was destroyed by an explosion and fire at the Four Courts in Dublin. As the Beyond 2022 website explains, seven centuries’ worth of Ireland’s historical records were lost in this fire.

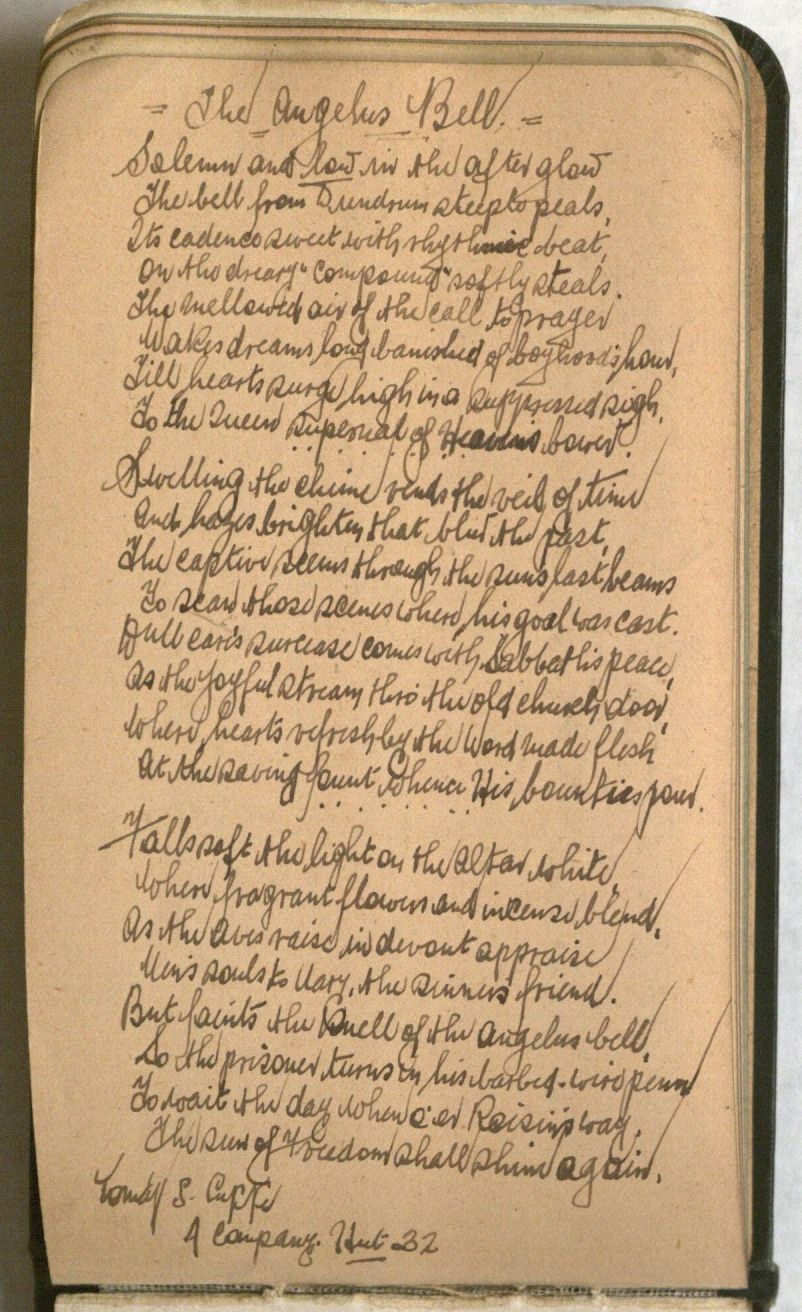

To overcome this harm to “Ireland’s collective memory,” Beyond 2022 is undertaking an international collaboration to digitize copies of records held across Ireland, Northern Ireland, and beyond in order to launch a “Virtual Record Treasury for Irish history—an open-access, virtual reconstruction of the Record Treasury destroyed in 1922.” One particularly exciting aspect of the initiative is its work with Transkribus to employ HTR (Handwritten Text Recognition) to automate the transcription of manuscript records.

Beyond 2022: Ireland’s Virtual Record Treasury. A short video about Beyond 2022, explaining the project. Video available at https://beyond2022.ie/?page_id=171#videos. Photo Credits: UCD Archives; National Archives of Ireland; Irish Architectural Archive; NoHo; Trinity College Dublin; ADAPT Centre.

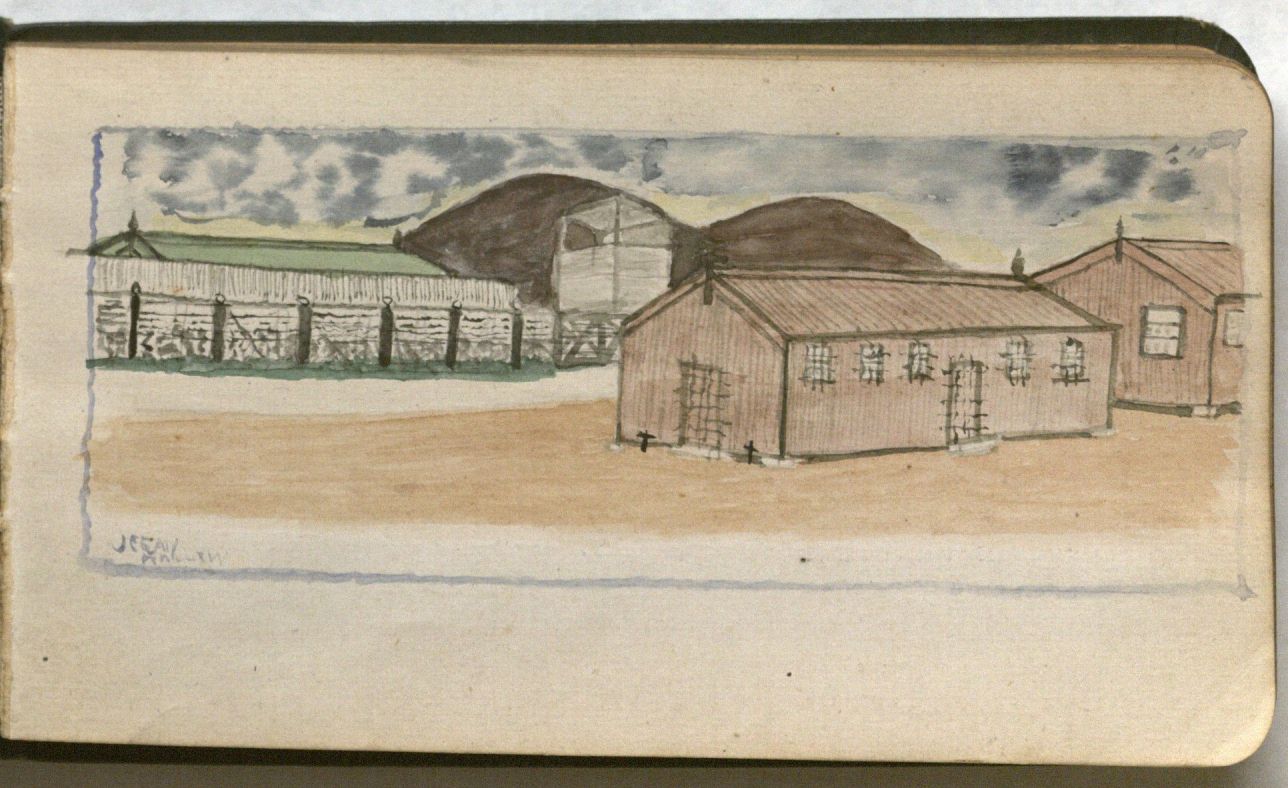

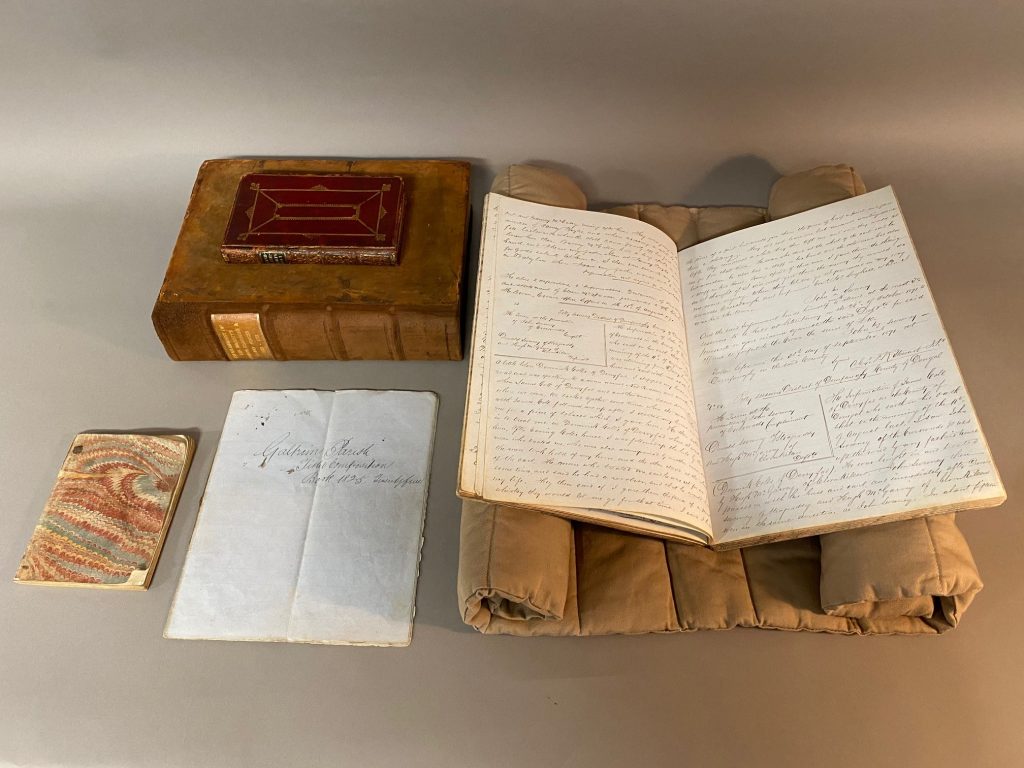

To assist in this ambitious effort, Spencer Research Library is digitizing several manuscripts from its collections that Beyond 2022 has identified as pertinent to its treasury. These manuscripts bearing on Irish history include volumes containing civil and military establishments for late 17th and early 18th century Ireland (MSD88, MS B86, and MS A42), a “Galtrim Parish tithe composition book,” Co. Meath, 1825 (MS P403A), and a volume containing “Copies of informations &c taken in Dunfanaghy Petty Sessions district, County Donegal,” 1863-1901 (MS E109). Such manuscripts are the types of records that might have once been held in the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI).

Of these, MS E109 is particularly intriguing. The manuscript volume contains copies of depositions, informations, statements, and declarations of complainants, witnesses, and occasionally defendants taken between 1863 and 1901 in the Dunfanaghy Petty Sessions district of Co. Donegal, a county in the northwest of Ireland bordering the Atlantic ocean. Petty Sessions were “courts held by the justices of the peace to try minor criminal offences summarily—i.e. without a jury.”[i] More serious cases would also be referred to other court proceedings, such as quarter sessions and assizes. (For a brief overview of the legal system in Ireland during the 19th century, visit the “History of the Law in Ireland” page on the website of The Courts Service of Ireland.)

Manuscripts such as the Dunfanaghy Petty Sessions district copy book can be particularly interesting to historians and genealogists alike because they offer views of the experiences and conditions of individuals for whom other types of written evidence may not exist or survive. For example, a significant number of those providing sworn informations and depositions in the Dunfanaghy copy book are recorded as having signed with their mark—the x or symbol that individuals unable to write would use in place of their signature. Such individuals are unlikely to have left other written documentation of their lives, such as letters or diaries, so their statements (though filtered through the clerk’s transcription) may be all that survives of their voices. Of course, it is worth remembering that a volume like the copy book for the Dunfanaghy Petty Sessions district isn’t necessarily capturing everyday life, but the experiences of individuals—whether complainants/victims, defendants, or witnesses—as their lives intersect with the legal system and crime.

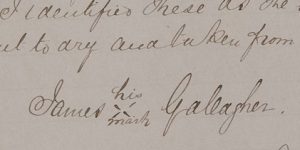

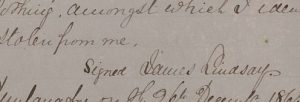

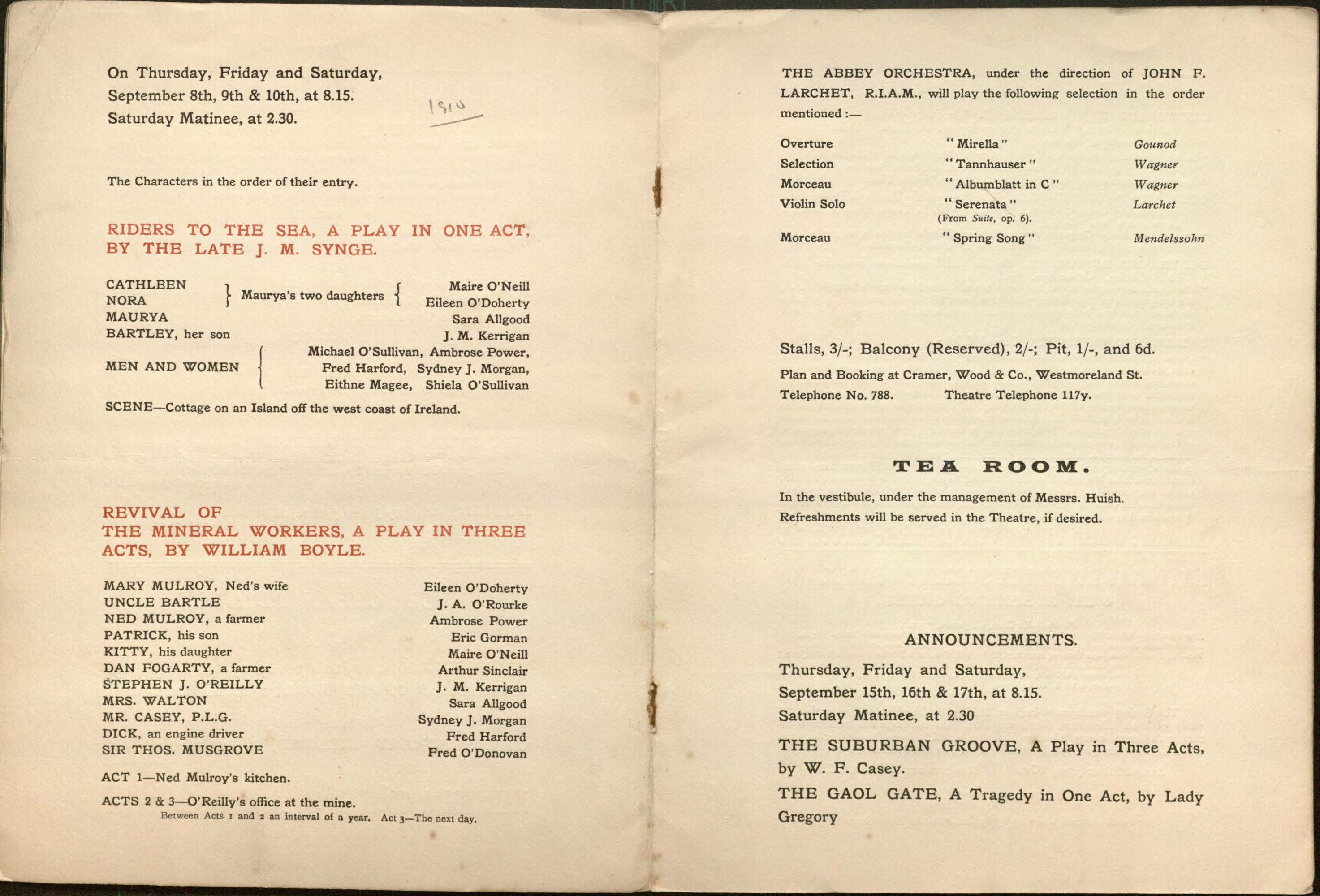

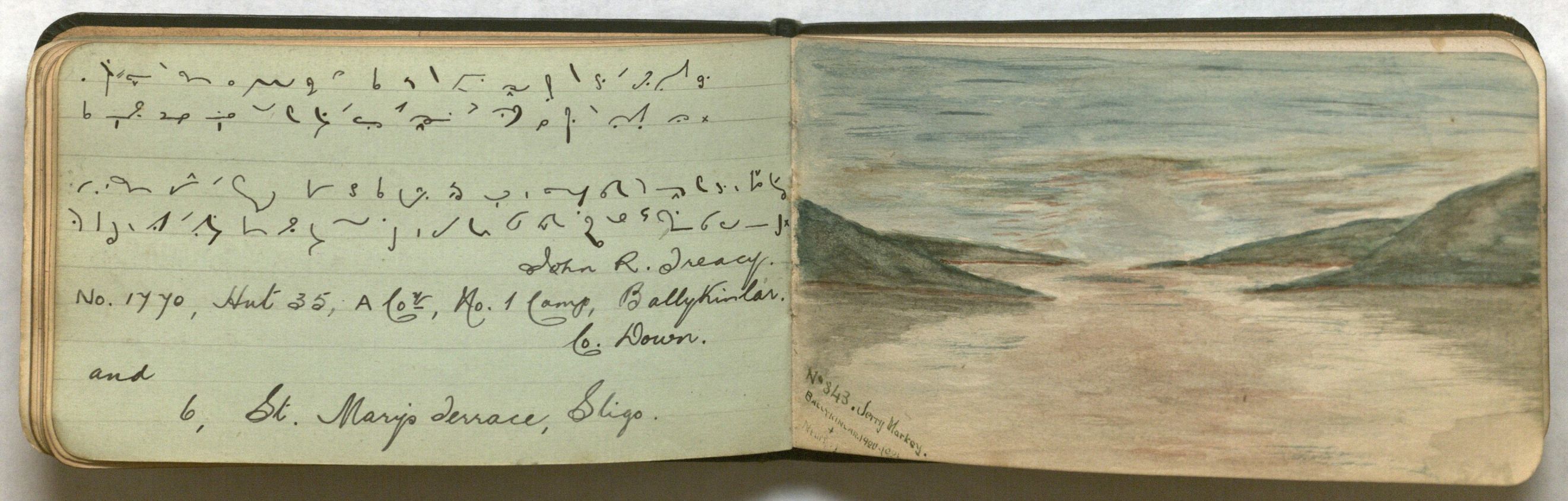

Details from the sworn “informations” of James Gallagher (Item 5) and James Lindsay (Item 6) concerning the theft of clothes hanging in their respective gardens in December of 1863. The notations in the copy book suggest that Gallagher (left) signed with his mark, whereas Lindsay (right) used a signature. “Copies of Informations &c taken in Dunfanaghy Petty Sessions district, County Donegal.” Dunfanaghy, copybook, 1863-1901. Call #: MS E109. Click here to see the full page containing the sworn information of both Gallagher and Lindsay.

The types of offenses recorded in the copy book include fights, theft (of clothes, of oats, of horses, sheep, and cattle, etc.), unlicensed guns, misappropriation of letters, threats of violence, and resisting the bailiff’s confiscation of a horse, to name a few. Occasionally the volume also contains accounts of more serious and violent crimes, such as assault and battery, murder, and rape. The witness and complainant statements for these matters can be quite harrowing to read. These cases would be referred to the assizes, the courts where the most serious offences (felonies) were addressed.

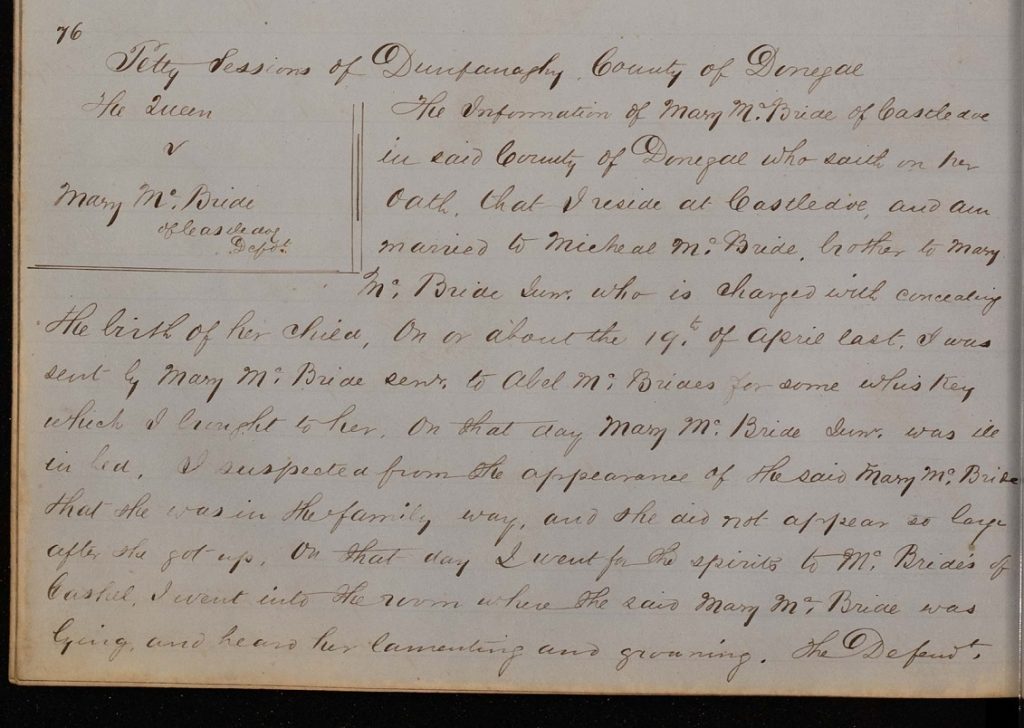

Several sworn statements offer glimpses into some of the difficult conditions of the lives of women. One example involves the case of Mary McBride, who in the spring of 1871 is accused of the concealment of the birth of a child. The sworn informations associated her case can be challenging to read, not only because of the difficult subject matter, but also because they make reference to no fewer than three Mary McBrides: 1) the woman who gave birth (sometimes referred to as Mary McBride junior); 2) that woman’s mother (Mary McBride senior); and 3) Mary McBride junior’s sister-in-law (Mary McBride, wife to Michael McBride). However, it is worth pushing through the confusion that the shared names might pose since the content of the statements is likely to hold much interest for researchers in the field of women’s history; women, gender, and sexuality studies; and the law.

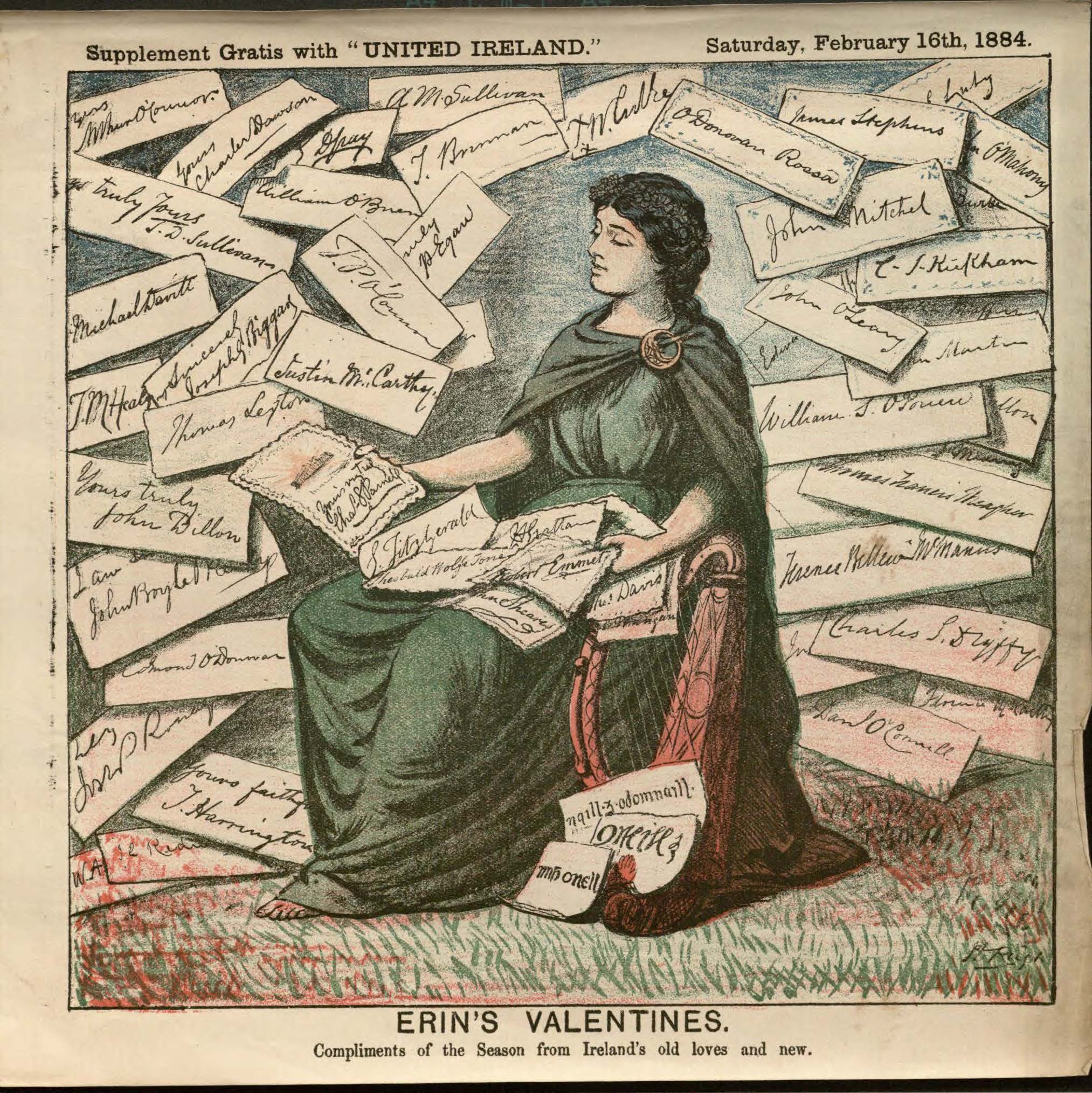

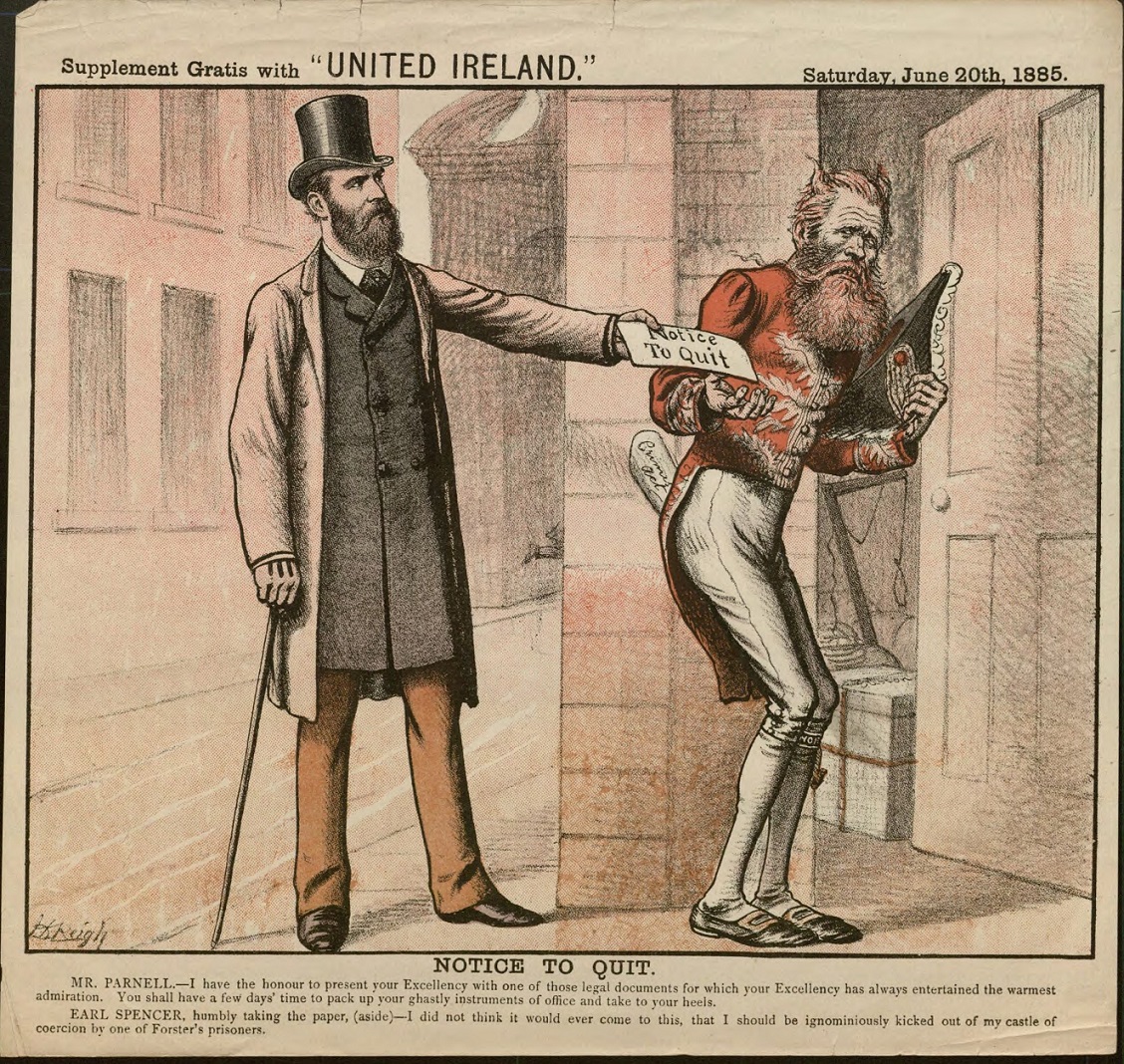

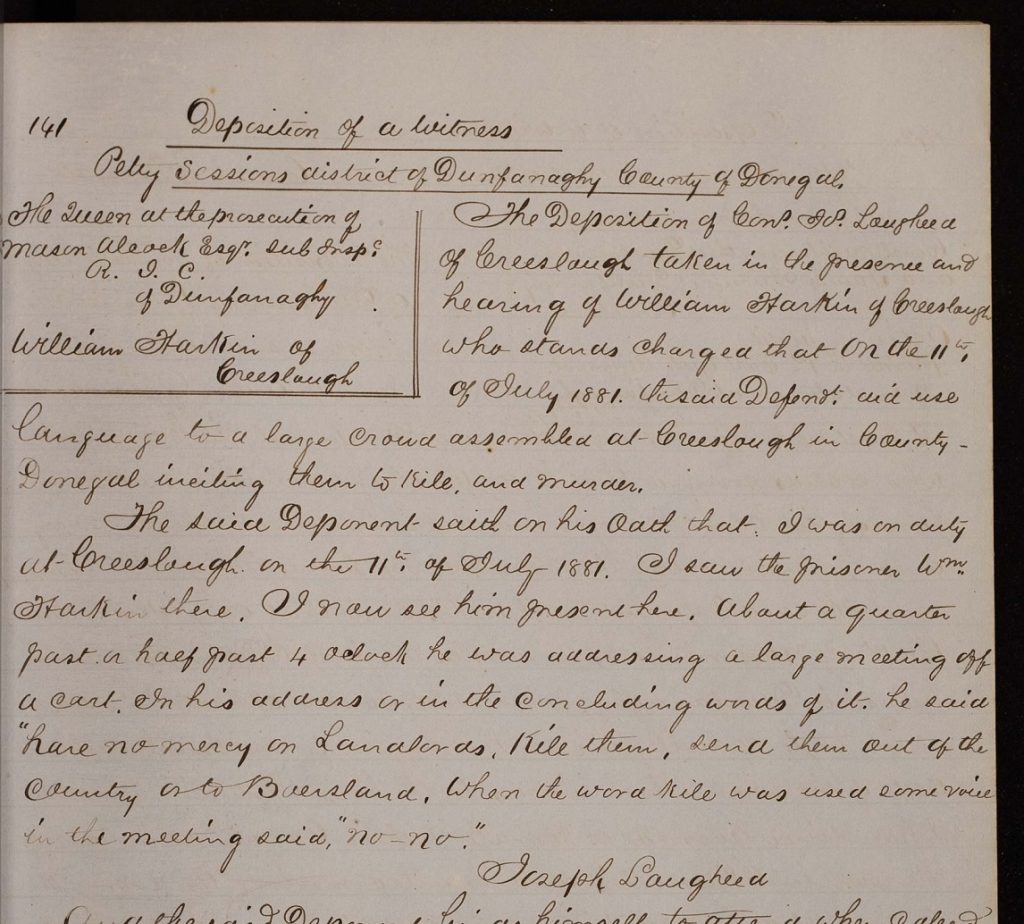

Though most of the cases are non-political, a few have a larger political valence. One notable instance relates to William Harkin of Creeslough, who is accused of inciting a meeting (which some witnesses referred to as a Land League meeting) to violence. The Land League was political agrarian organization that campaigned against landlordism and its more predatory practices, seeking rights for farmer tenants, such as fair rents, rights to sale of occupancy, and security of tenure. The date of the incident recorded in the Dunfanaghy copy book, July 11, 1881, falls during a period of heightened agrarian agitation referred to as the Land War, and indeed, later that year, the Land League would be suppressed and several of its national leaders, including Michael Davitt and Charles Stewart Parnell, jailed. The Dunfanaghy copy book contains witness statements of three members of the Royal Irish Constabulary against Harkin. Constable Joseph Lougheed’s brief deposition reports, “In [Harkin’s] address or in the concluding words of it, he said ‘have no mercy on Landlords. Kill them, send them out of the country into Boersland.[’],” although he also notes, “When the word kill was used some voices in the meeting said, ‘no-no.’” News of the charges against Harkin reached as far as New South Wales, where Sydney’s The Freeman’s Journal reported on it a month and a half later as part of a section on the Land War, under the heading “A Land League Secretary Charged With Inciting to Murder.”[ii] The depositions surrounding Harkin’s case may appeal to students and scholars studying Irish nationalism, reform movements, and agricultural history alike.

In the coming months, the five selected manuscripts will be made available online through Beyond 2022’s Treasury and in KU Libraries’ own digital collections, enabling researchers around the world to make new investigations into Irish history. On this St. Patrick’s Day, following a full year during which so many of our activities have migrated online in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s exciting to think that students, scholars, and members of the public will soon be able to read (and make discoveries with) several of Spencer’s Irish manuscripts from wherever they can access a computer.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

[i] Mulholland, Maureen. “Petty sessions,” in The Oxford Companion to British History. Oxford University Press, 2015. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199677832.001.0001/acref-9780199677832-e-3360.

[ii] “A Land League Secretary Charged With Inciting to Murder,” The Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, NSW). Vol. XXXII, No. 1958 (17 September 1881): 7. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/12664516.