Brown v. Board of Education Resources at Spencer Research Library

August 11th, 2021For over fifty years it was legal to segregate elementary children in the United States into schools based on the color of their skin. In Kansas, unless the town had a population less than 15,000, Black and white children went to different elementary schools.

Less than a half-hour drive west from the University of Kansas campus is the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site. Located in Topeka, Kansas, this important historic site is one of the origins of the Supreme Court case that marked the end of legal racial segregation in the nation’s public schools.

The court case was five separate lawsuits brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to the Supreme Court. One of the five lawsuits was filed against the Topeka Board of Education after the local NAACP assembled a group of thirteen African American parents and instructed them to attempt enrollment of their children in a segregated all-white school near their home. As anticipated, they were denied. All total the parents attempted enrollment in eight of the eighteen segregated all-white schools in the city. The Topeka School Board had established only four schools segregated for the city’s African American children. One of those parents was Oliver Brown. When the case was filed his name headed the roster of Topeka plaintiffs. On appeal to the United States Supreme Court the Topeka, Kansas, case was consolidated with cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. The high court ruled on the cases under the heading of the Kansas case, Oliver L. Brown et al vs. the Board of Education of Topeka (KS) et al. The unanimous decision was announced on May 17, 1954, with the court finding that racially segregated schools violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The decision marked a turning point for the pursuit of equal opportunity in education.

The court case was complicated and is difficult to describe in a few paragraphs. Fortunately, there are good resources that provide a summary of the history, such as the website for the Brown Foundation, the progenitor of the National Park Site. The Brown Foundation was the leader of the community’s success in establishing the Brown v Board National Historic Site in 1992. They created the concept and worked with Congress to establish it. The Foundation’s website contains a wealth of information and curriculum materials that can be ordered for classroom teachers. The website for the National Park Service’s Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site contains excellent information on the story of Brown v Board of Education and civil rights. In addition, resources such as the KU Libraries’ publication Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a project of the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research, give a greater understanding of the court case and the individuals involved.

For those wanting to conduct in-depth research on the court case and the circumstances behind it, Spencer Research Library has many primary resources available.

Although the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site was closed to visitors during COVID-19, I wanted to see if there were any volunteer opportunities. When I contacted the volunteer coordinator, Dexter Armstrong, in October 2020, he was open to suggestions for off-site volunteering projects. I offered to assemble a list of local primary resources to not only aid their staff, but also any visitors, teachers, or site researchers that may need it. He agreed that a list of local primary resources would be a valuable tool.

Listed below are the Brown v. Board of Education resources and closely related material at Spencer Research Library.

Online Exhibits

Education: The Mightiest Weapon

Curated by Deborah Dandridge, Field Archivist and Curator, African American Experience Collections

Archival Resources

Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research Records

Date Range of Materials: 1970-2017

Call Number: RH MS 876

The records in this collection are those of the Topeka, Kansas-based Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research, established in 1988 as a tribute to the 1954 Brown v. Topeka Board of Education case and its plaintiffs and participants. These records include general information on the foundation and related subjects and events.

Paul Wilson Papers

Date Range of Materials: 1962-1995

Call Number: RH MS 746

Paul Wilson was a Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Kansas, who, prior to his University service, participated in the Brown v. Board of Education case on behalf of the State of Kansas. This collection contains research and notes on Wilson’s book, A Time to Lose: Representing Kansas in Brown v. Board of Education.

See also:

- Paul Wilson’s oral interview with the Endacott Society, an organization for retired KU faculty, staff, and spouses (Call Number: UA RG 67/754)

- Paul Wilson talks about Brown v. Board of Education (Call Number: UA RG 44/1, cassette tape 0329)

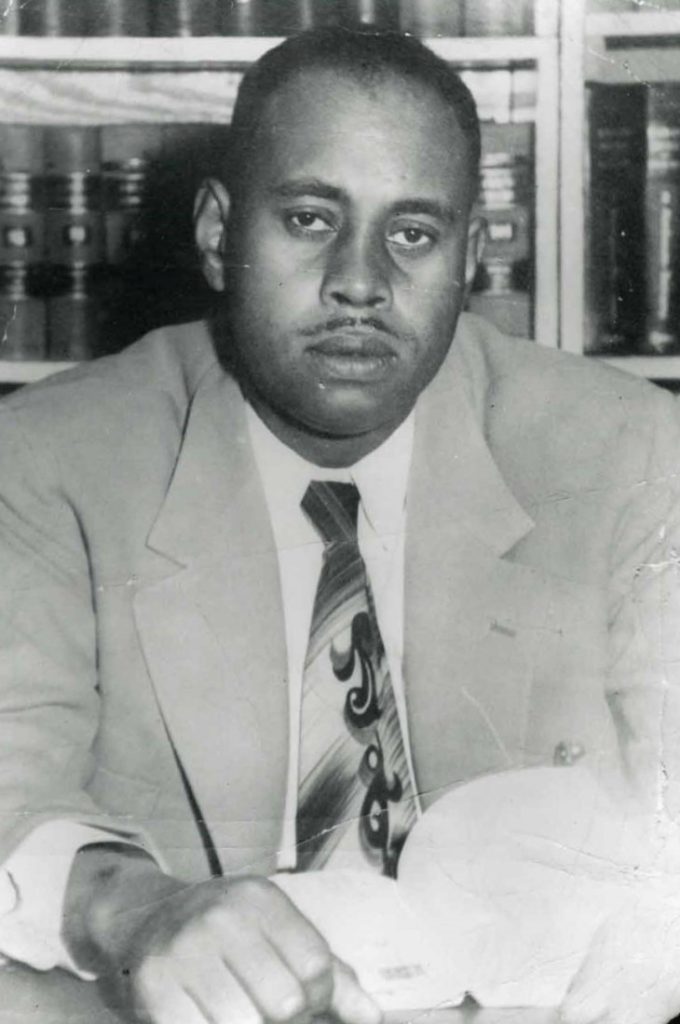

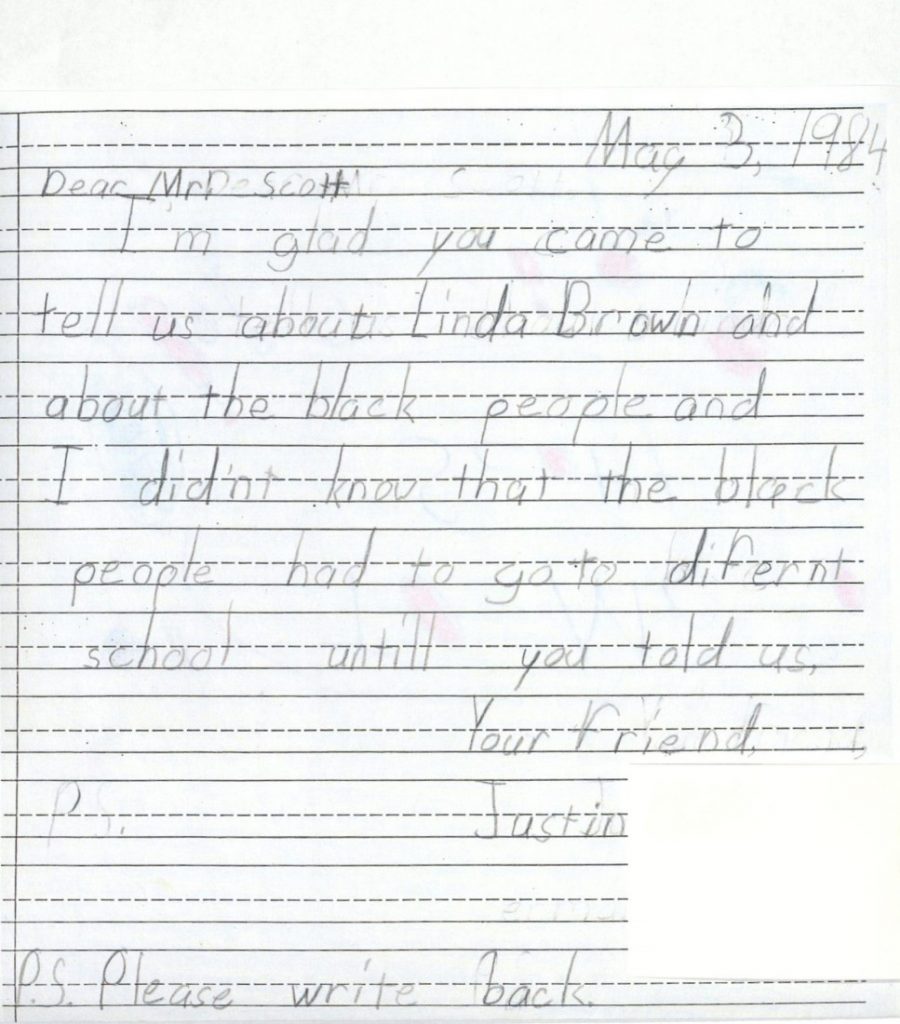

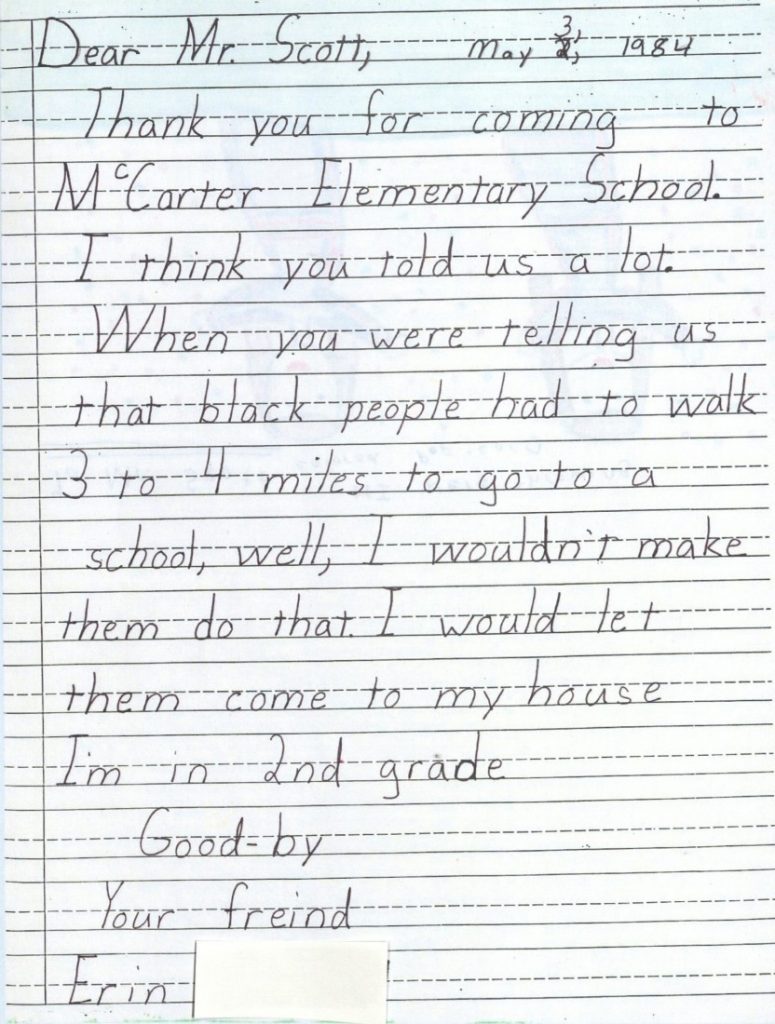

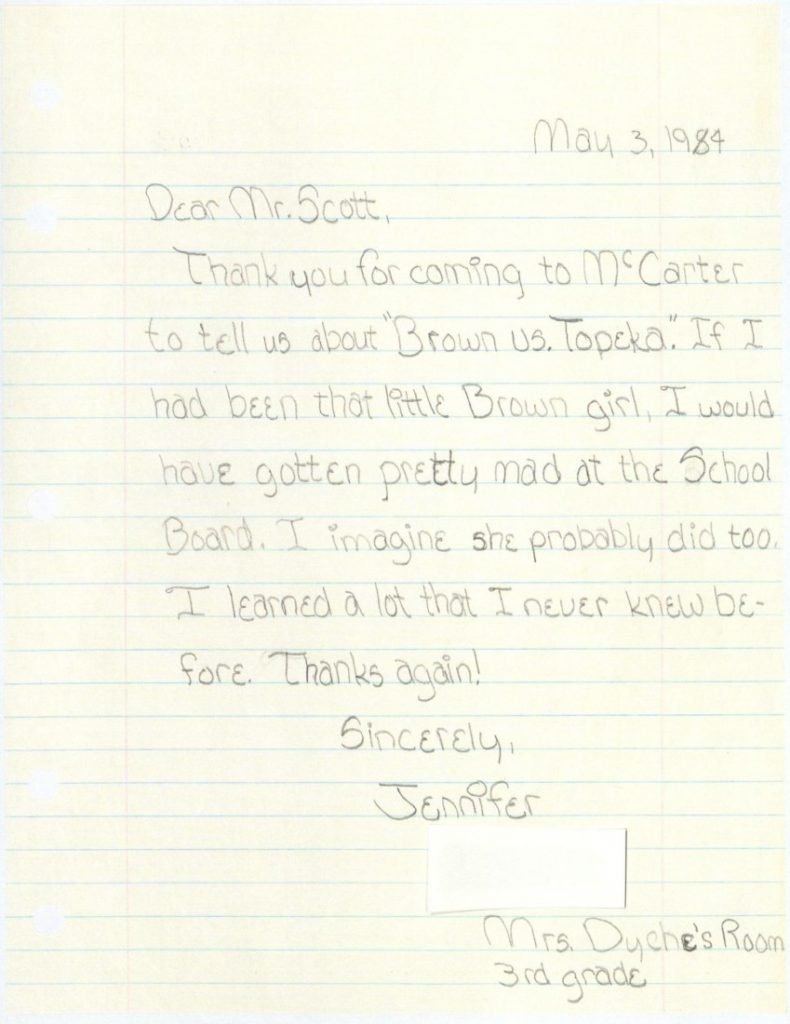

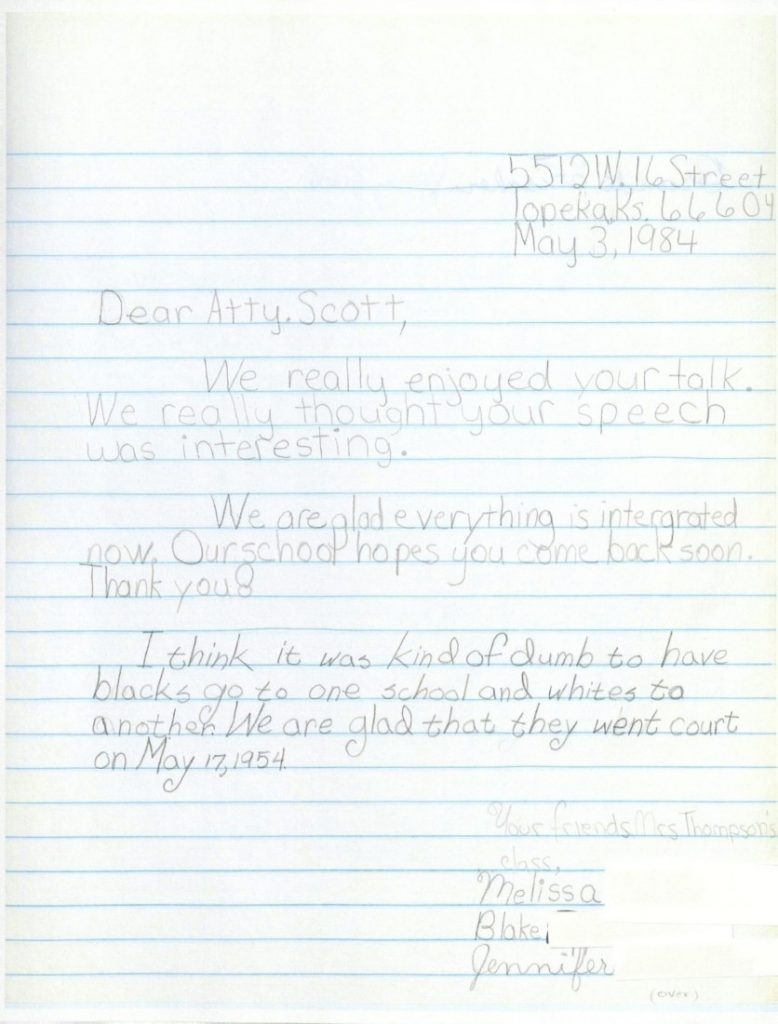

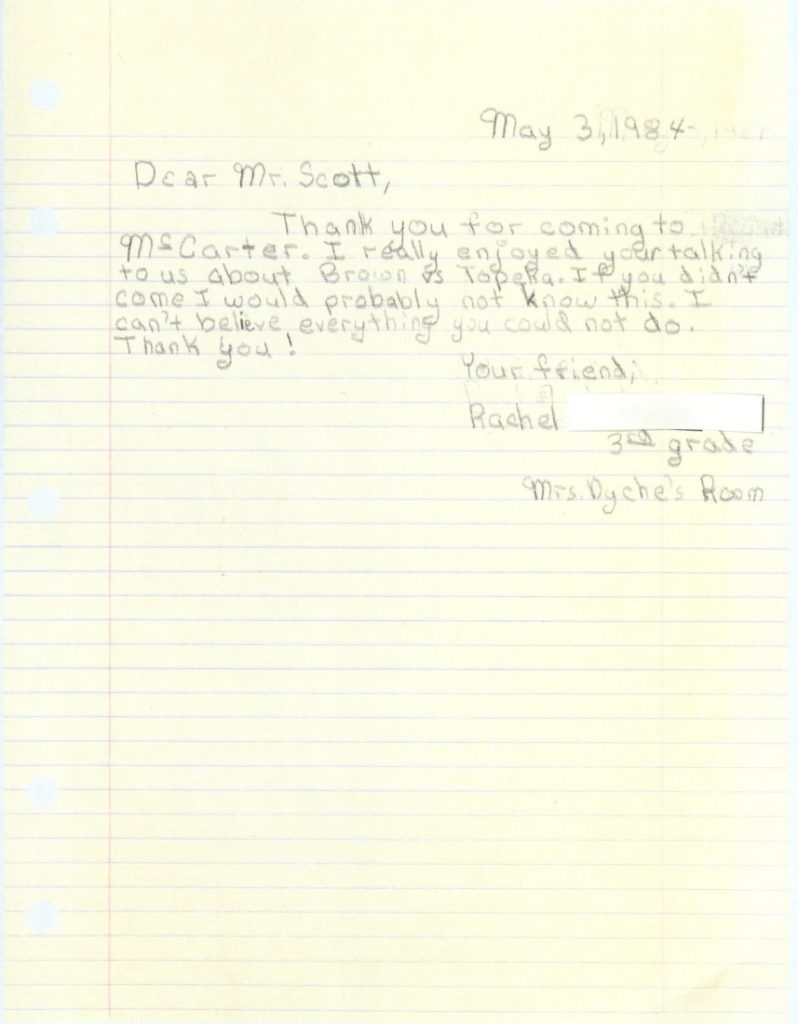

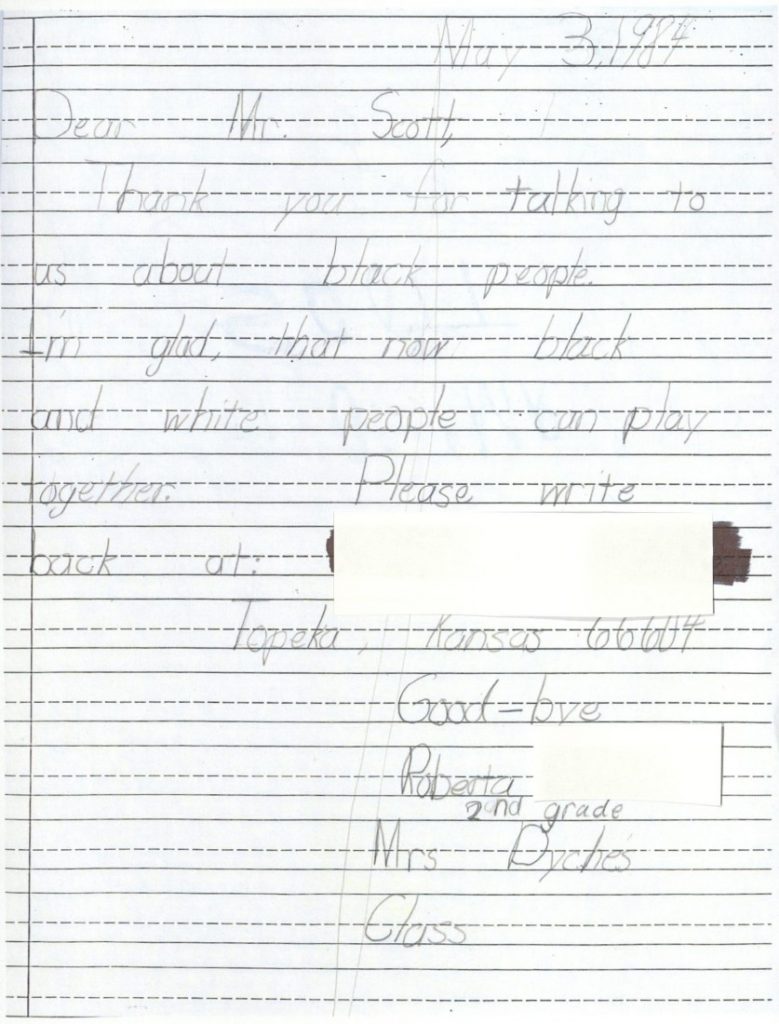

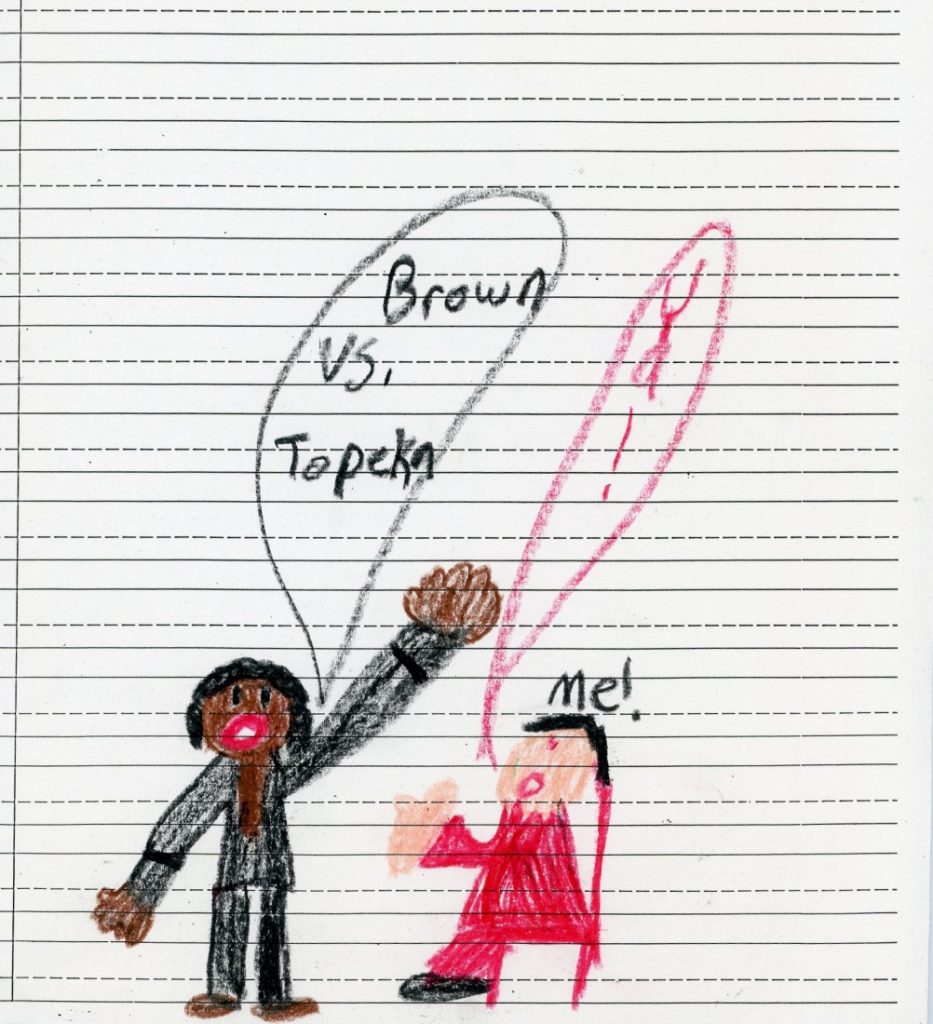

Charles S. Scott Papers

Date Range of Materials: 1918-1989

Call Number: RH MS 1145

The Charles S. Scott Papers are those of a prominent native Topeka, Kansas, lawyer who focused on civil rights and was one of the plaintiff’s lawyers in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case.

Records of the Topeka Back Home Reunion

Date Range of Materials: 1975-2010

Call Number: RH MS 1291

The Topeka Back Home Reunion originated in 1973 thanks to the efforts of Charles Scott, Carl Williams, and Eugene Johnson. The purpose of the Reunion was to bring together those who attended the four elementary schools in Topeka, Kansas, designated for Black students (Buchanan, McKinley, Monroe, and Washington) before the 1954 Brown v. Board U.S. Supreme Court decision and, later, African Americans who attended Topeka schools after 1954. The Reunion took place triennially, supplemented by regular meetings and newsletters. The final reunion took place in 2010.

State Street Elementary School Photograph

Date Range of Materials: circa 1944

Call Number: RH PH P16

This collection contains one photograph of a fifth-grade classroom at the State Street Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas. The print shows teacher Louise Becker helping her class with a penmanship lesson; student Ruth Lassiter-Snell stands in front of the teacher.

Topeka Public Schools Class Photographs

Date Range of Materials: 1892

Call Number: RH PH 151

This collection contains class portraits from the public schools in Topeka, Kansas, in 1892.

Jesse Milan Papers

Date Range of Materials: 1931-2012

Call Number: RH MS 623

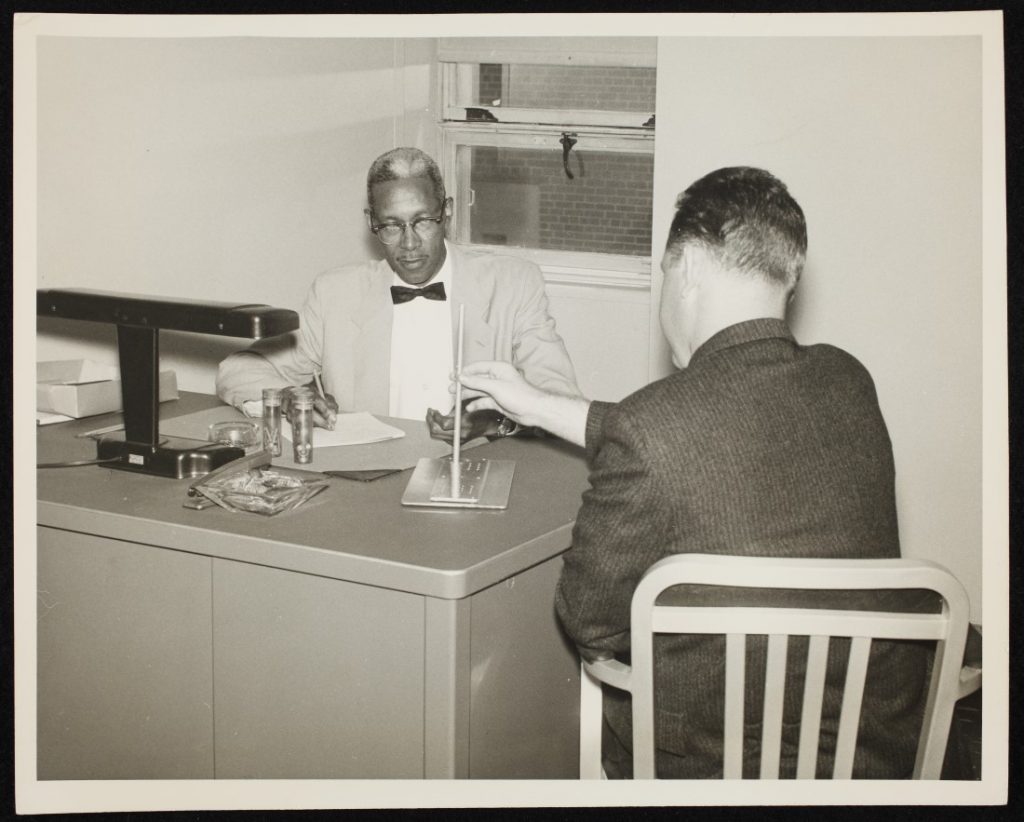

Jesse Milan, a longtime resident of northeast Kansas, was the first African American teacher to serve in the integrated Lawrence Unified School District #497. An active community leader, he was involved in the fiftieth anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education commemoration and other Brown v. Board of Education projects. He later became an Assistant Professor of Education at Baker University in Baldwin City, Kansas.

Cheryl Brown Henderson Campaign Papers

Date Range of Materials: 1968-1979; 1989-1998

Call Number: RH MS 1190

This collection contains the papers of Henderson’s political campaigns. Cheryl Brown was born in 1950 to Oliver L. and Leola (Williams) Brown. Following her family’s involvement in the landmark Brown v. Topeka, Kansas Board of Education, Brown attended public schools in Topeka, Kansas, and Springfield, Missouri. She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Baker University (Baldwin, Kansas) and a Master of Science degree in Counseling from Emporia State University. Cheryl Brown married Larry Henderson in 1972. She worked as a classroom teacher and, from 1979 to 1994, as a consultant to the Kansas State Board of Education. In 1988 she co-founded the Brown Foundation for Educational Equality, Excellence, and Research and served as its Executive Director. In 2010 Henderson served as the Superintendent of the Brown v. Board National Historic Site.

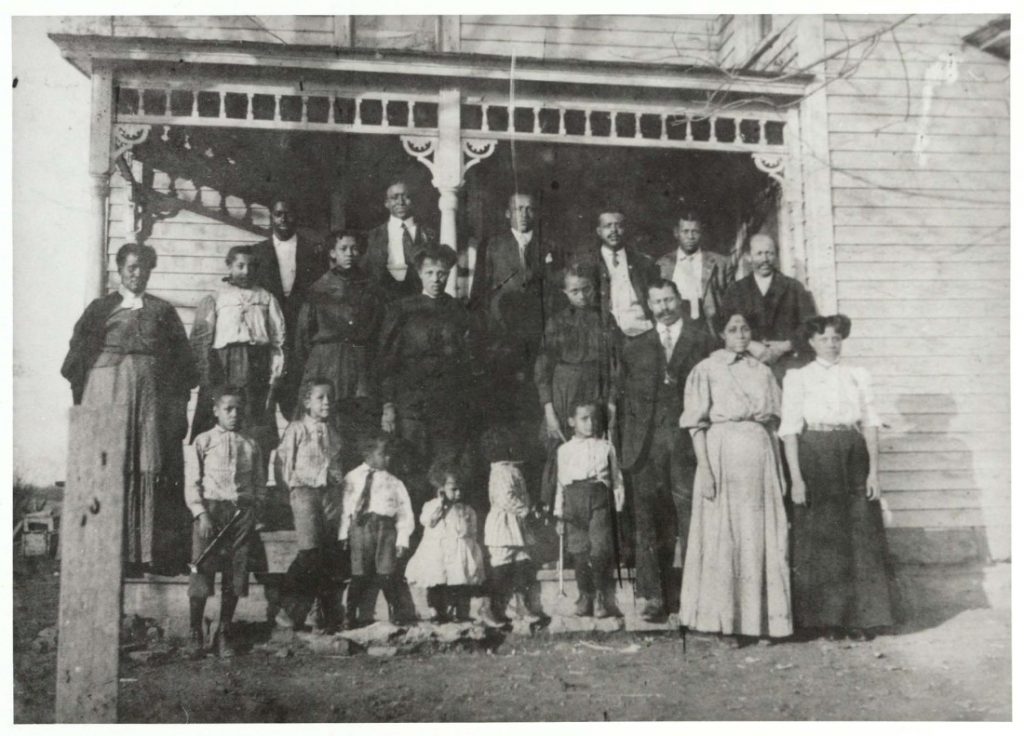

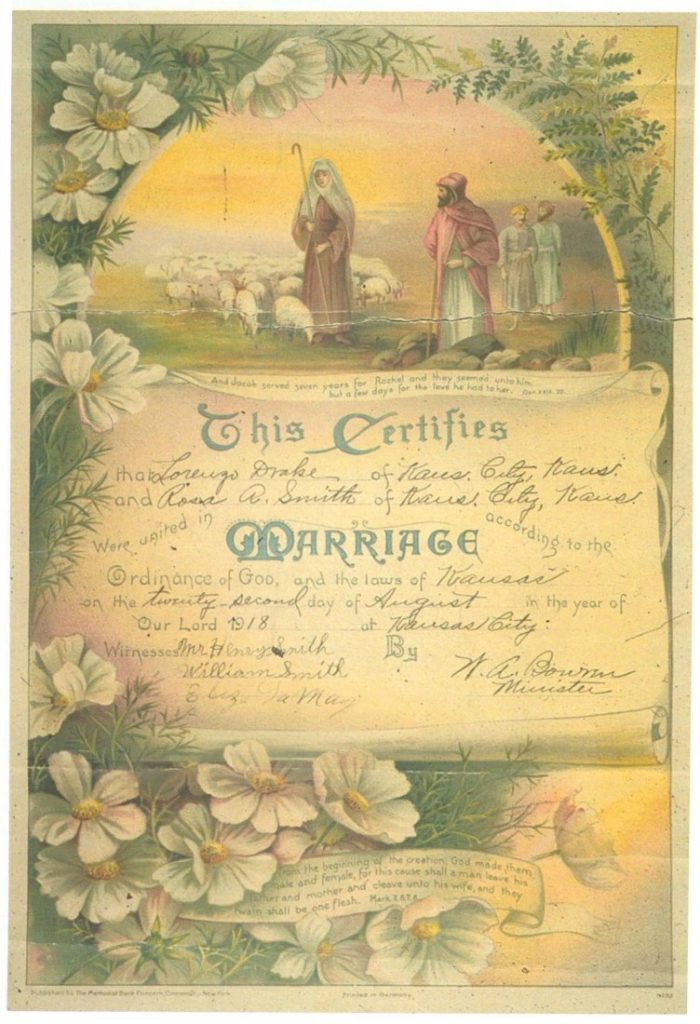

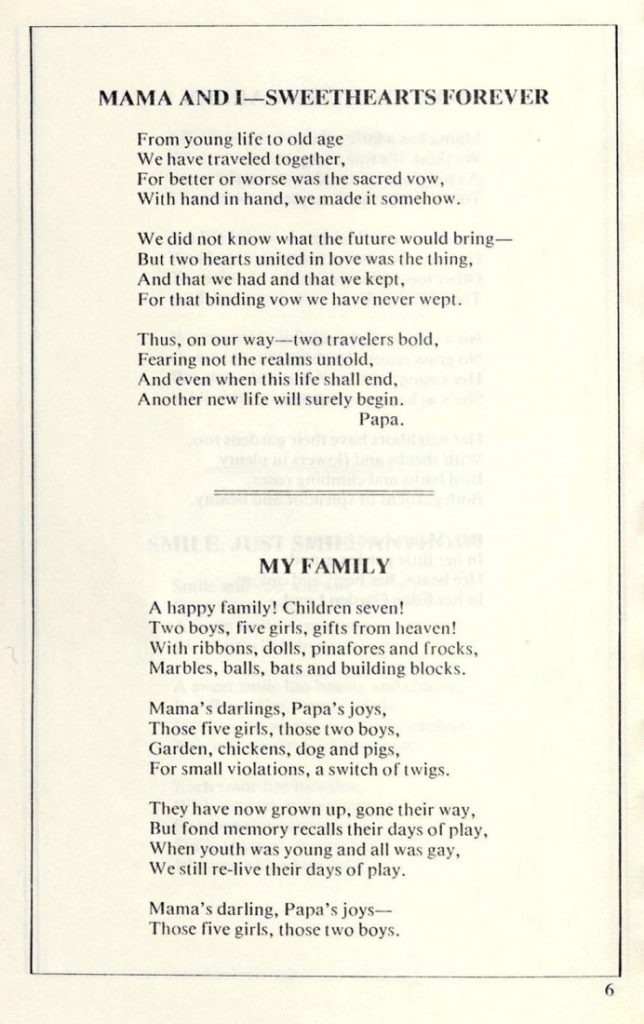

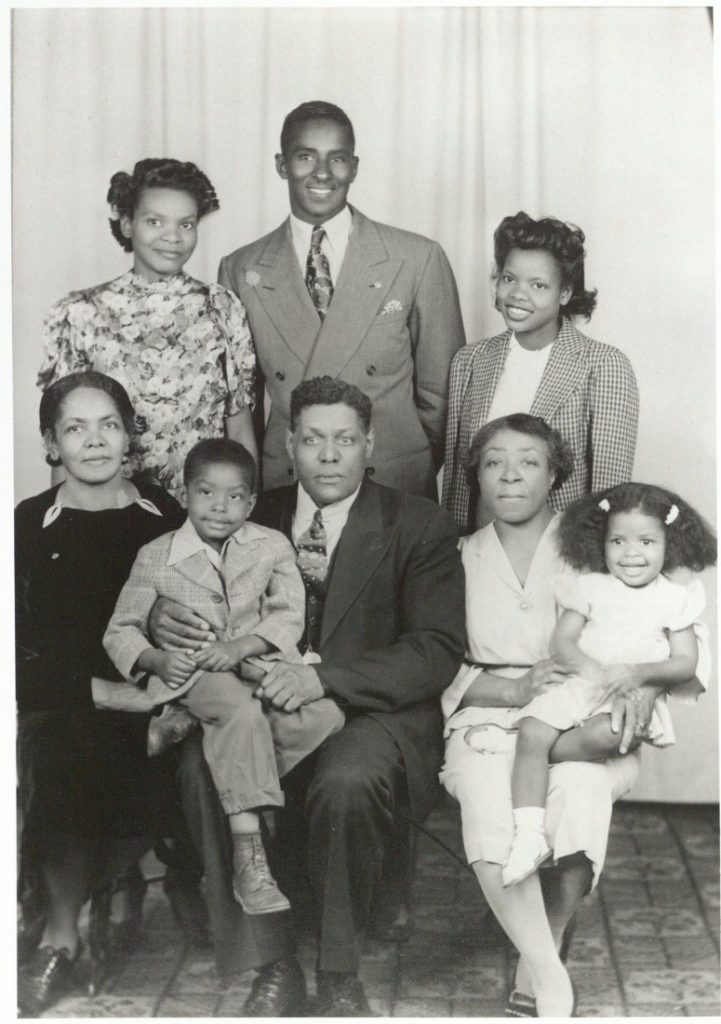

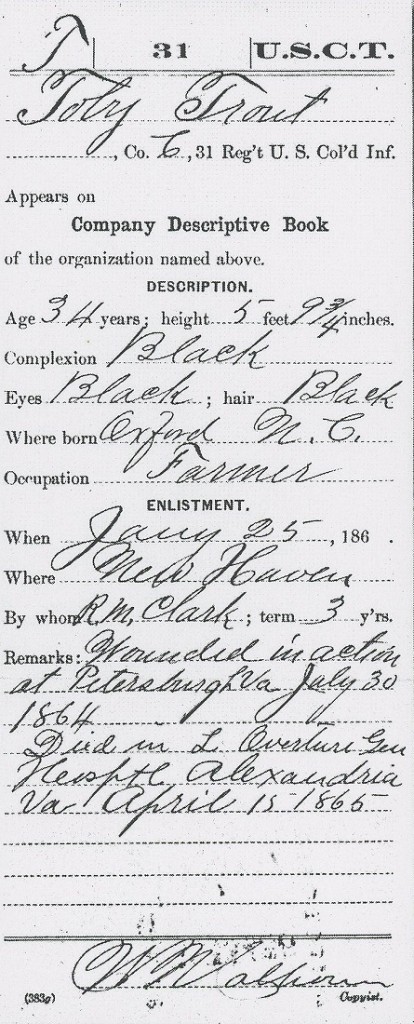

Nathaniel Sawyer Family Papers

Date Range of Materials: circa 1880-2012 (bulk 1950s-1990s)

Call Number: RH MS 1460

Nathaniel Sawyer was an active opponent to the expansion of segregation in Kansas schools, helping to defeat a 1918 legislative bill that would have allowed communities with as few as 2,000 people to segregate their public schools. Sawyer’s family members were prominent in Topeka. They were involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and had some involvement with the Brown v. Board of Education case.

To view these materials in person, contact Spencer Research Library. Besides the collections listed, pertinent materials can be found in other collections at Spencer, such as the single photograph (above) of Ms. Abbott’s kindergarten class in the Joe Douglas Collection. Be sure to speak with our knowledgeable reference staff during your visit. They can help you find information relevant to your topic.

I suggest also visiting the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka to experience in-depth, thought-provoking exhibits. Visitors to the site leave with an understanding of how Topeka’s schools led to the Supreme Court declaring that “in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

To see the complete local primary resource, which also includes resources at the Kansas Historical Society and the Eisenhower Library, contact the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site. Special thanks go to Dexter Armstrong, Park Ranger at the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, for his support and encouragement for the list of local primary resources.

Lynn Ward

Processing Archivist