Manuscript of the Month: Signs in the Margins and Between the Lines

May 26th, 2021N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

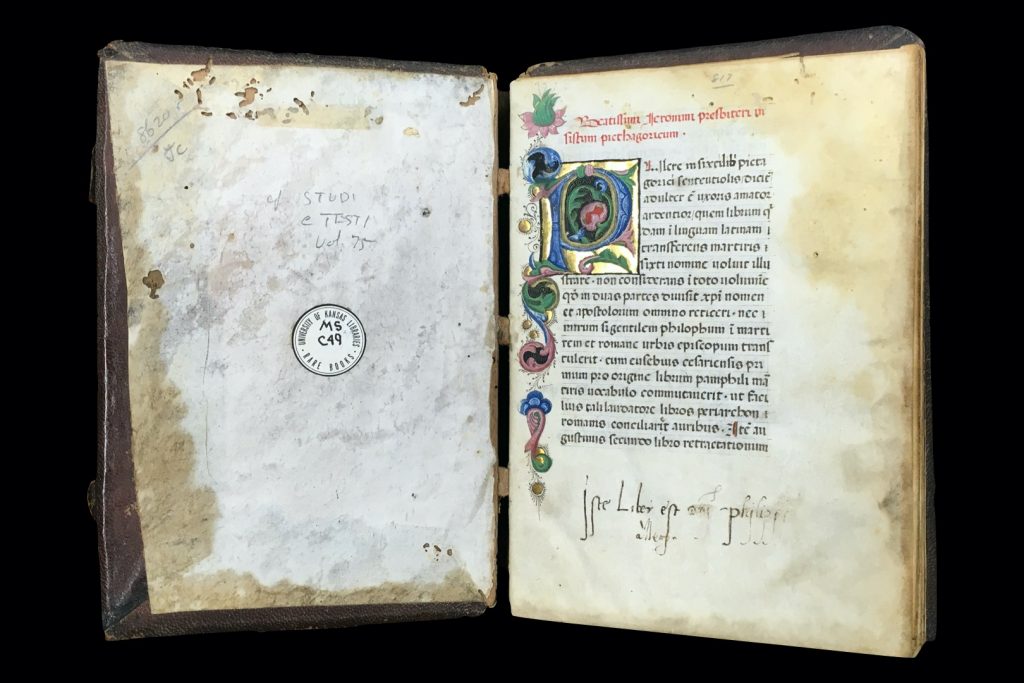

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS C49 contains copies of two works which were originally composed a millennium apart: the translation of Sextus Pythagoreus’s Sententiae from Greek into Latin by Rufinus of Aquileia (345–410) and the Enchiridion by Laurentius Pisanus (approximately 1391–1465). Both works are collections of sayings, usually of moral nature, and the genre of sententiae (i.e., sentences) goes back to the classical times. Considering its age, MS C49 is in relatively good condition despite heavy water damage that caused discoloration of parchment on the upper part of the manuscript towards the fore-edge. The manuscript was copied by a single scribe, probably in the third quarter of the fifteenth century in Italy, and it probably is still in its original binding. We do not have any information on the exact origin or the history of the manuscript, except for an unidentified ownership inscription in the lower margin on folio 1r, which indicates that the manuscript once belonged to a Philippus (“Iste liber est d[omi]ni Philippi […]”: This book belongs to master Philippus […].)

In addition to this ownership inscription, there is a series of other writings and markings in MS C49, especially in the margins of the first part of the manuscript which contains the Sententiae. Originally written in Greek in the late second or early third century, the Sententiae by Sextus Pythagoreus includes about 500 sayings. The Latin translation by Rufinus of Aquileia in the late fourth or early fifth century, which includes 451 of these sayings, is mostly literal, although there are alterations to the text as with any late antique or medieval translation. In MS C49, the text opens with an extended version of Rufinus’s preface, and even though the sayings are copied as if they were a prose text and not numbered, they can be easily identified as each saying begins with a capital letter highlighted in red.

All text and marks in the margins of a manuscript are collectively called marginalia. There can be several reasons for marginalia in a manuscript; some are left by the scribes of the manuscripts and others by the readers or later owners of the manuscripts, such as the ownership inscription on folio 1r. After the copying of a text in a manuscript, for example, often scribes or others working with them would check the copy against the exemplar, the manuscript from which the copy was made. This was to ensure that the copy of the text was correct and complete, similar to modern proofreading and copyediting practices. Sometimes, they would also check the copy they had against another copy of the same text, especially if they thought what was copied was not reliable or there was lacuna in the exemplar. During both of these processes, if they encountered a missing word or a phrase, or a discrepancy, they would note this down, usually in the margins of the manuscript and sometimes in between the lines. Interventions and alterations of any kind to the main text frequently also included the use of different types of signs. Centuries later, similar practices are still in place today in the academic and publishing worlds. See, for example, the Proofreader’s Marks provided by the Chicago Manual of Style. It is possible to discern how this methodology works even when the copyediting or proofreading is done electronically, for example, via Microsoft Word Track Changes or Adobe Acrobat Comments.

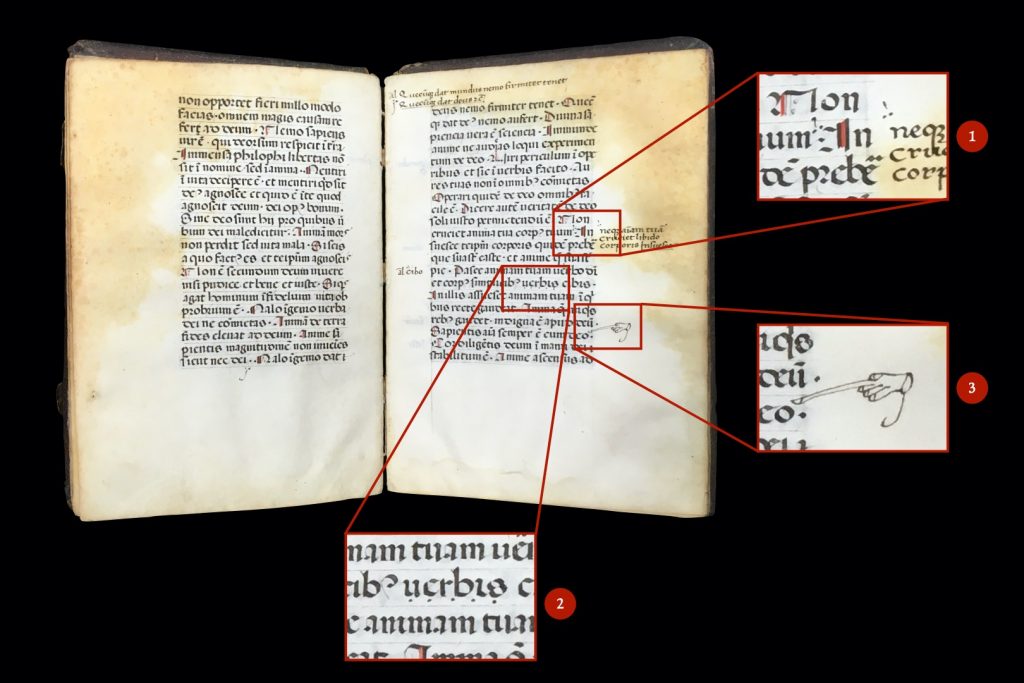

In the case of MS C49, most of the marginal and interlinear additions and corrections seem to have been made by the same hand, either the scribe who copied the text or a contemporary who could have been another scribe, an editor or a reader. Since this second hand mostly adds corrections to the main text, we can be fairly certain that they were checking the copied text against the exemplar. Here are three examples of interventions from folio 17v:

In the first case, the text is corrected by adding a missing sentence in the outer margin. This usually happens when the scribe originally skips a word, a phrase or a sentence and later notices that they made a mistake. Instead of copying the entire page again, which would be costly and time consuming, they make a note of the missing passage. In order to ensure that the additional text is inserted into the right place, the place where the insertion needs to be made in the main text is first marked with a sign and later a corresponding sign is placed together with the additional text in the margin. In this case, the sign employed in MS C49 looks like an exclamation mark with two dots. These types of signs are called signe-de-renvoi (i.e., “sign of return”) or tie marks. They are used in pairs and link the main text to a marginal annotation.

In the second example, on line 15 of folio 17r, the word “verbis” has a series of dots underneath. In this case, it seems that the scribe made another mistake by copying a word that is not part of the text. In these cases, again, instead of copying the entire page, they signaled a deletion of the extraneous word or phrase. There are differing practices to indicate a deletion in medieval and early modern manuscripts, depending on the scribe and where and when a manuscript is copied. What is used here is an omission technique called subpuncting or underdotting, in which a series of dots are placed under the letter or the word that is to be omitted from reading. Today, one usually crosses out a passage or a word when there is a mistake. Nevertheless, this medieval practice is thought to have given way to the modern ellipsis, which indicates omitted words in a text.

The sign seen in the third example has a slightly different use; it is not a direct intervention to the text. Instead, it is utilized to mark an important passage. The symbol in the shape of a pointing hand is called a manicule (from the Latin word manicula, meaning “little hand”), and it is found in the margins of medieval manuscripts and later on in printed books to draw attention to a section of a text. There are over two dozen manicules in MS C49. If this pointing hand sign seems familiar, it is because it is the same symbol that one sees when one moves their pointer over a hyperlink today!

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Charles S. Boesen in February 1959, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

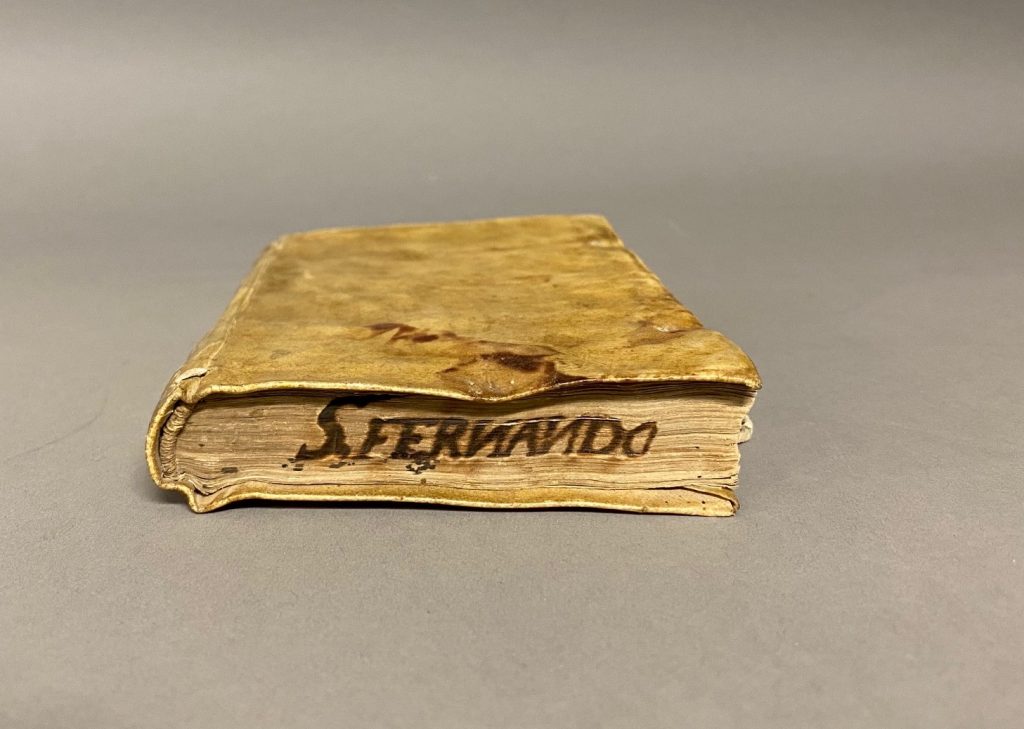

![Marcas de fuego from the Convento de san Agustín (Puebla, Puebla) on Spencer Research Library's copy of Biblia polyglotta. Alcala de Henares: in Complutensi universitate, industria Arnaldi Gulielmi de Brocario, 1514-1517 [i.e. 1520 or 1521]. Call # Summerfield G41.](https://exhibits.lib.ku.edu/files/original/46c9f79ac0226357bb080b0e11e0f47d.jpg)