A Holinshed’s Chronicles Provenance Puzzle

February 6th, 2018Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland is widely regarded as a book that inspired and informed many of William Shakespeare’s history plays, as well as tragedies such as Macbeth and King Lear. Last year Kenneth Spencer Research Library (KSRL) purchased the first edition (1577) with the aim of making the book and its 212 lively woodcut illustrations available to visiting classes and researchers. The bookseller’s description said that this copy had been in private family ownership for generations, but we never dreamed that it would be possible to trace the book back to its original owner. After unpacking the two volumes, we leafed through them page by page looking for manuscript annotations.

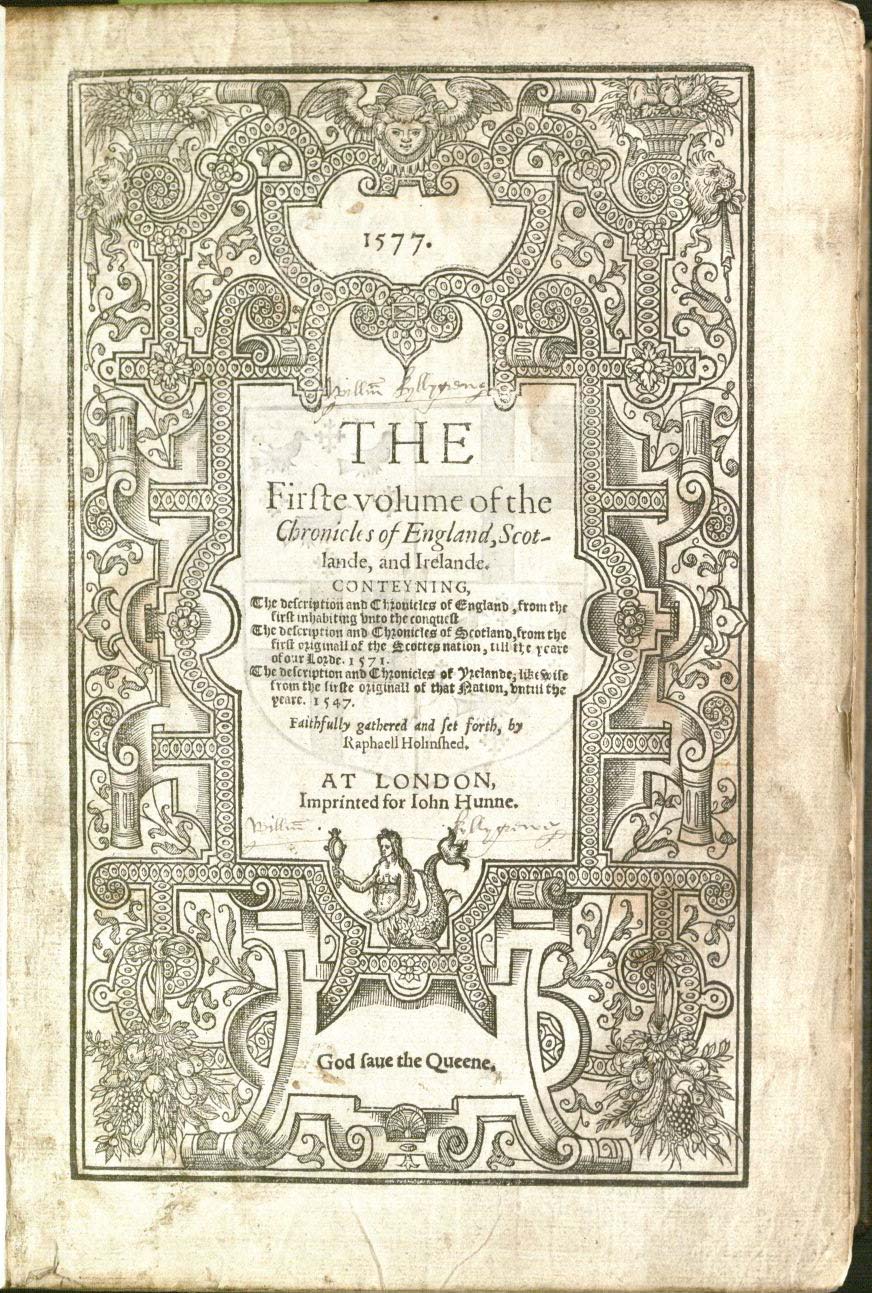

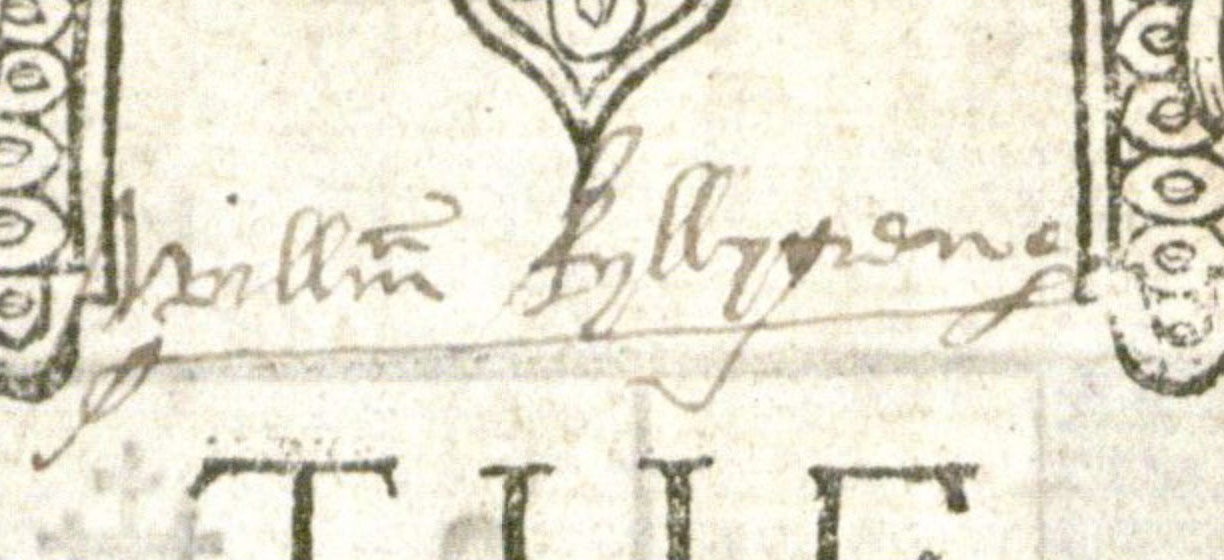

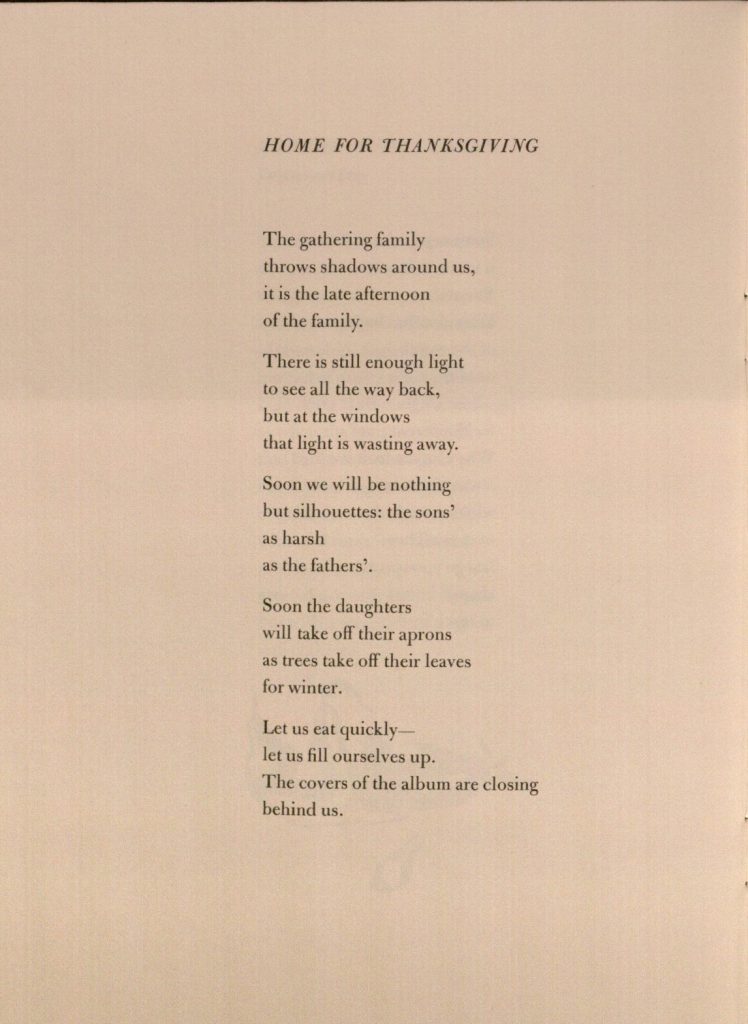

On the title page of volume one “William Kyllygrewe” had signed his name twice in Tudor script:

Title page of Volume 1 of Raphael Holinshed’s

Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande.

At London: Imprinted for Iohn Hunne, 1577.

Call Number: Pryce D11. Click image to enlarge.

Could William Kyllygrewe have been the original owner of the book? Browsing through the rest of the book revealed some marginal notes and manicules (sketches of a pointing hand) marking passages of interest to some past reader. There is no other handwritten evidence of ownership.

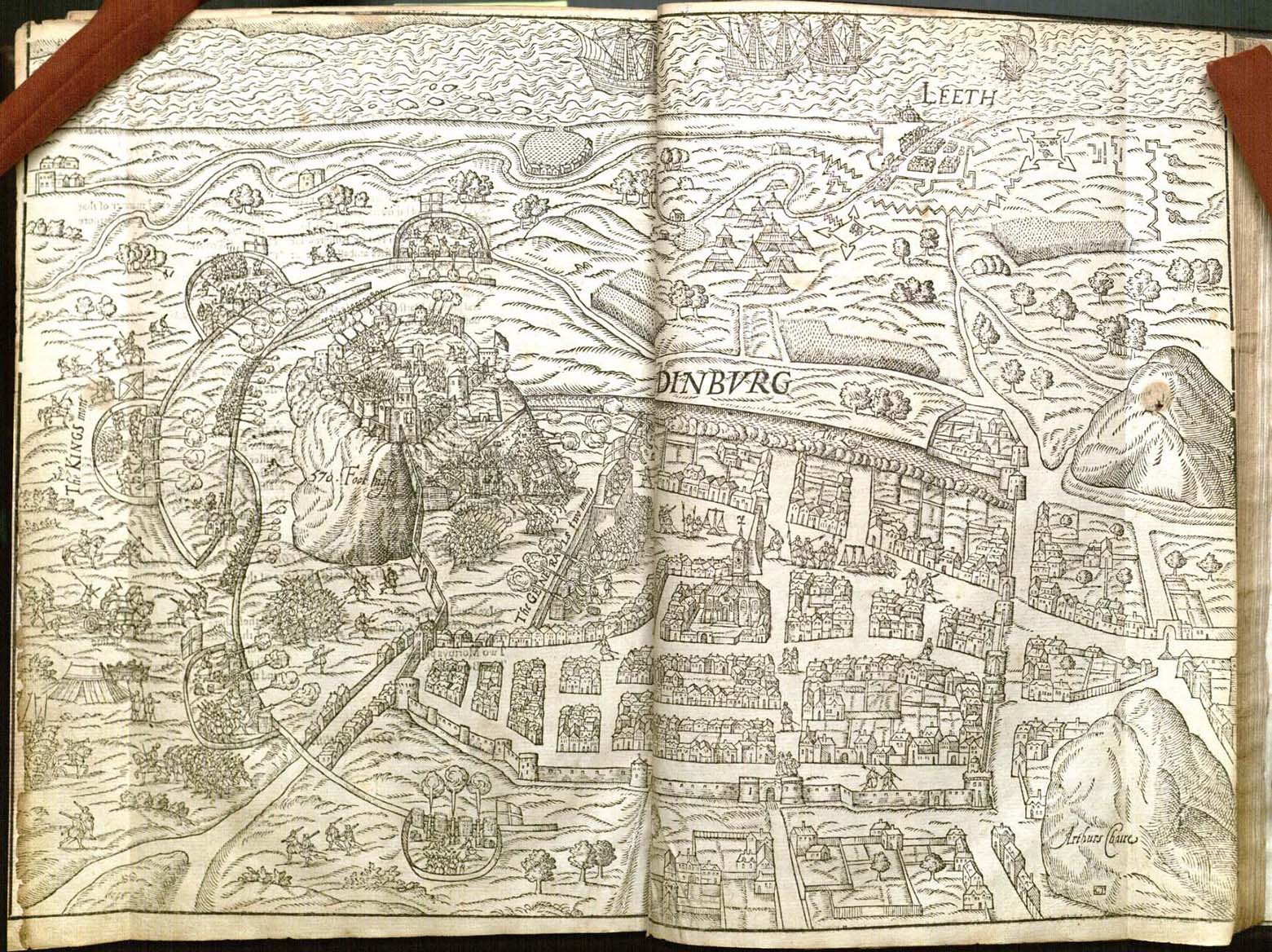

However, there is an eye-catching pictorial map in the section about the reign of Queen Elizabeth I that concludes volume two. The text recounts the conflict between the Catholic forces supporting Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Protestant forces of Queen Elizabeth during 1571-1573. The hostilities culminated in the “Lang Siege” of Edinburgh Castle.

The map shows the Protestant artillery bombarding Edinburgh Castle before achieving victory.

Map of the siege of Edinburgh Castle, from Vol. 2 (following page 1868) of

Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande.

Call Number: Pryce D11. Click image to enlarge.

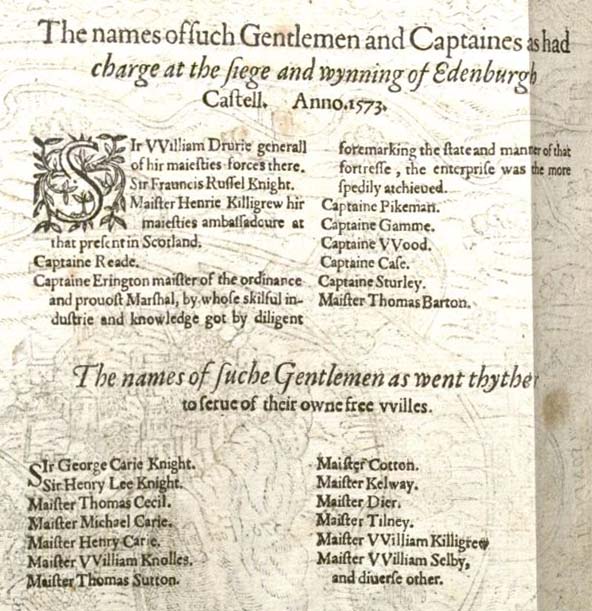

Text on the back side of the map lists the chief participants in the siege. General Sir William Drurie commanded the Protestant forces with the aid of ten Gentlemen and Captaines. One of them was “Henrie Killigrew hir maiesties ambassadoure at that present in Scotland.” Listed next are thirteen “Gentlemen as went thither to serve of their owne free willes.”

Among the gentlemen who participated “of their own free willes” is William Killigrew.

List of participants in the siege from the verso of the map of Edinburgh castle,

from Vol. 2 (following page 1868) of Holinshed’s Chronicles of England,

Scotlande, and Irelande. Call Number: Pryce D11. Click image to enlarge.

Allowing for the variations in spelling usual at that time, could he be the William Kyllygrewe who owned this book? In his shoes, wouldn’t you want to own a book in which you and your brother are mentioned as major players in a recent military victory?

Some genealogical investigation of the Killigrew family tree with its numerous Henrys and Williams revealed that the Henry Killigrew (d. 1603) and William Killigrew (d.1622) were the fourth and fifth sons of John Killigrew and Elizabeth (née Trewennard) of Arwennack in Cornwall. As younger sons they needed to make their own way in the world and did so successfully as royal courtiers. William was elected Member of Parliament a number of times and was appointed to various government offices, including Groom of the Privy Chamber to Elizabeth I in 1576 and Chamberlain of the Exchequer under James I in 1608. In 1594 he took an 80-year lease on Kempton and Hanworth, adjoining royal manors in Middlesex near London. In 1603 he was knighted.

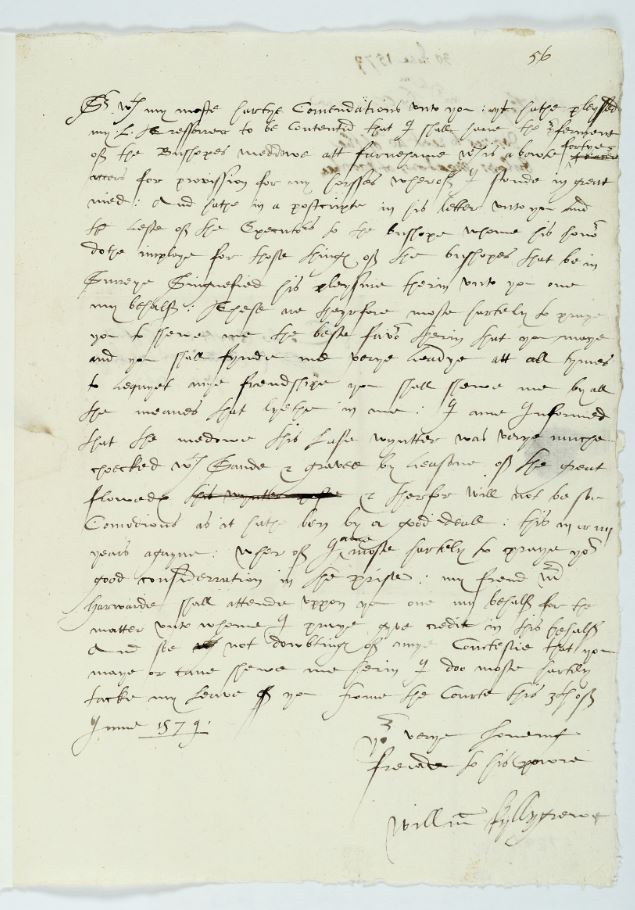

While the biographical information did not answer the question whether this William Killigrew had owned our copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles, his prominence suggested that surviving documents signed by him might be located and compared with our owner’s inscription. The Discovery database at the website of The National Archives at Kew near London in England led to an archival record in the Surrey History Centre for a letter held written by William Killigrew to Sir William Moore on 3 June 1579, just two years after the publication of Holinshed’s Chronicles.

Killigrew’s letter concerns the Bishop of Winchester’s meadow at Farnham in Surrey.

Letter from William Killigrew to Sir William Moore, 3 June 1579.

Surrey History Center. Letter Ref. Number 6729/1/56.

Reproduced by permission of the More-Molyneux family and

Surrey History Centre. Click image to enlarge.

Killigrew planned to pasture his horses there but was asking Moore, one of the Bishop’s executors, to reduce the rent because the meadow was “very much choked with sand and gravel by reason of the great floods.” It was exciting for us to discover that the Killigrew signature on the letter is a close match to the ownership inscriptions in our Holinshed’s Chronicles.

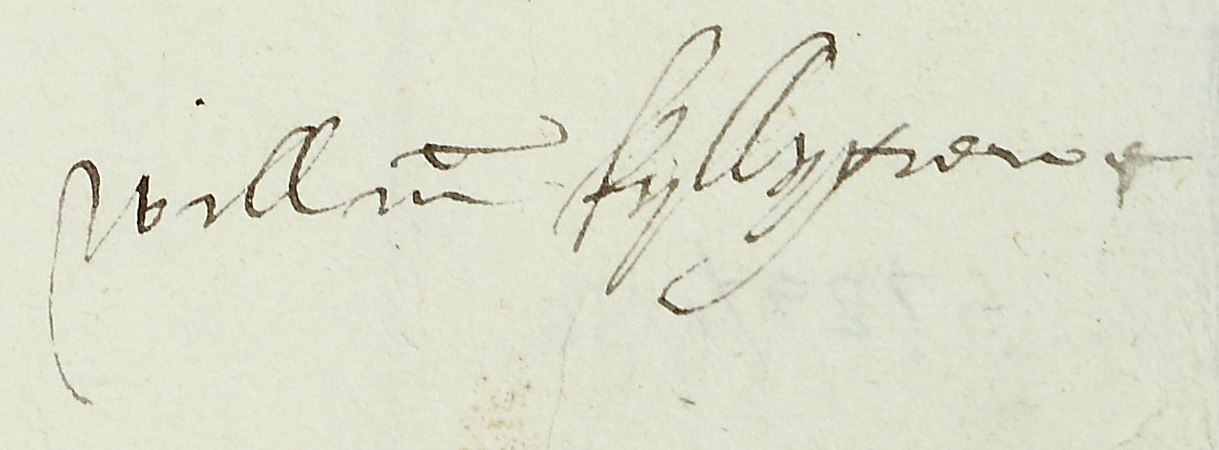

Details of William Killigrew’s signatures: Holinshed’s Chronicles (left)

and the letter to Moore (right). Click image to enlarge.

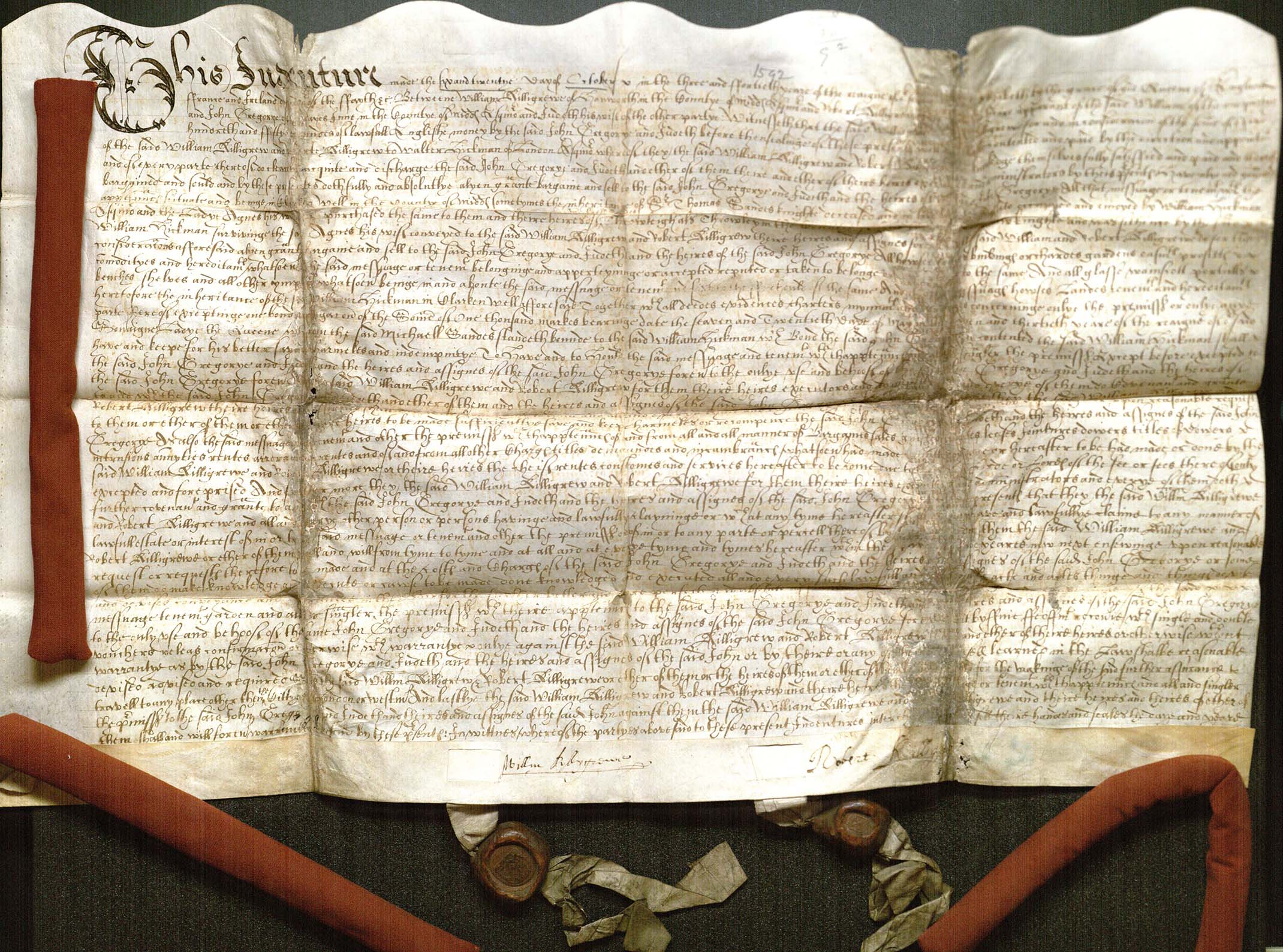

In fact, the search for a William Killigrew signature need not have led so far afield. Kenneth Spencer Research Library’s large collection of English Historical Documents includes, as it turns out, a 26 October 1601 deed of covenant by William Killigrew and his son, Robert, agreeing to sell a messuage (dwelling house, outbuildings, and land) in Clerkenwell Parish, Middlesex to John Gregorye and his wife, Judith.

William Killigrew’s signature is clear at the bottom of the deed, although Robert’s signature to the right is only partly legible

Deed of covenant signed by William Killigrew, 26 October 1601.

A Miscellany of Deeds and Manorial, Estate, Probate and Family Documents, 1194-1900.

Call Number: MS 239: 2357. Click image to enlarge.

Once again, the signatures match.

Details of William Killigrew’s signatures: Holinshed’s Chronicles (left)

and Killigrew-Gregorye deed (right). Click images to enlarge.

The manner in which the copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles descended from the hands of William Killigrew in family ownership until Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased it is still uncertain. The bookseller’s description suggests that a female Killigrew relative may have taken the book with her when she married into the Grenville family. More research remains to be done.

Karen Severud Cook

Special Collections Librarian