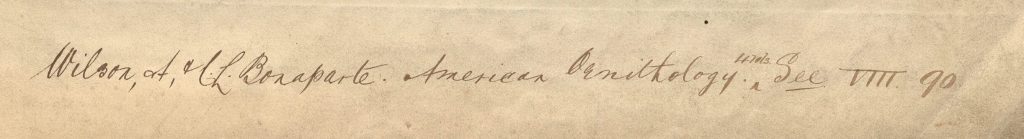

Spencer’s November-December Exhibit: “Creating Over a Century of Symphonies: The Reuter Organ Company”

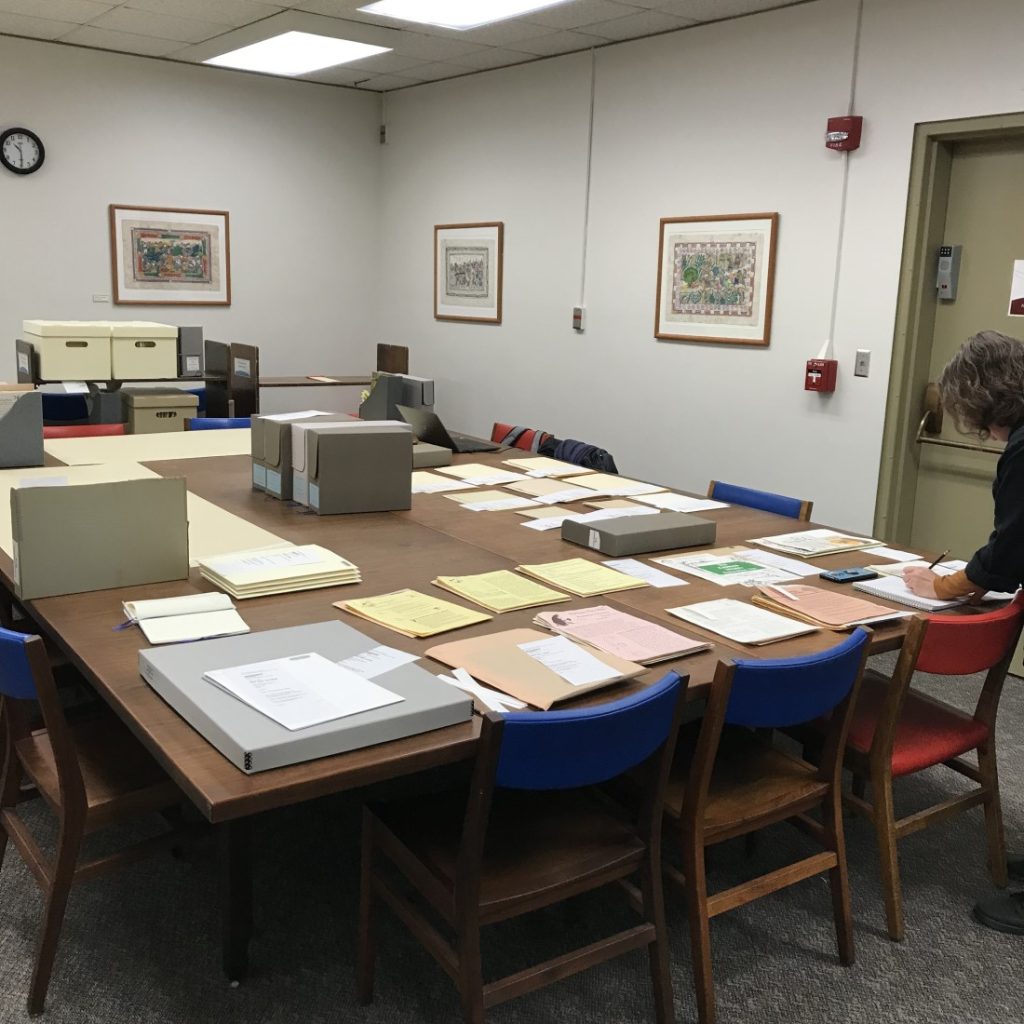

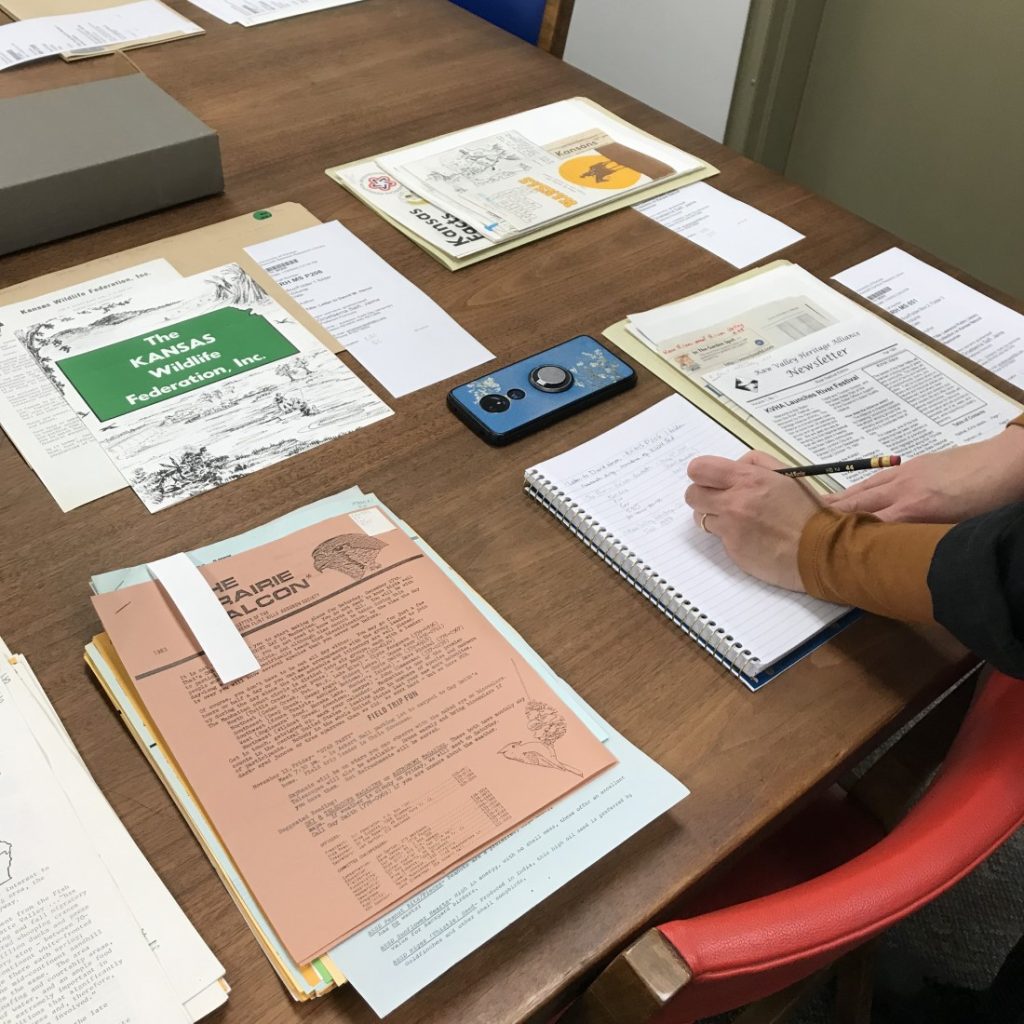

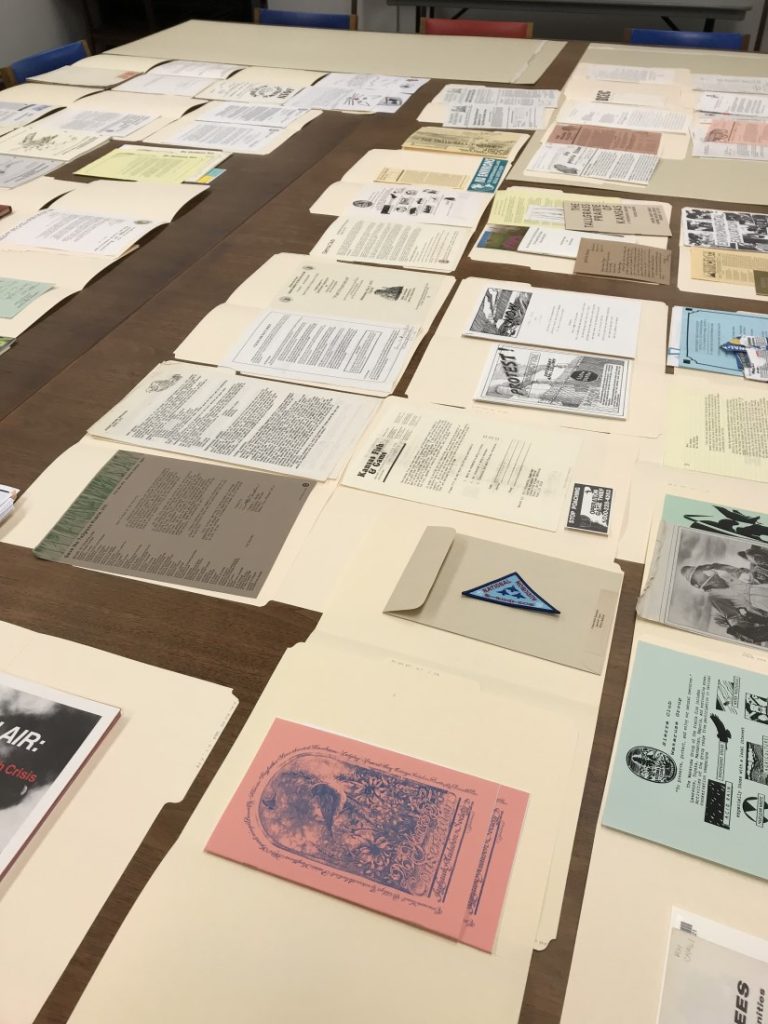

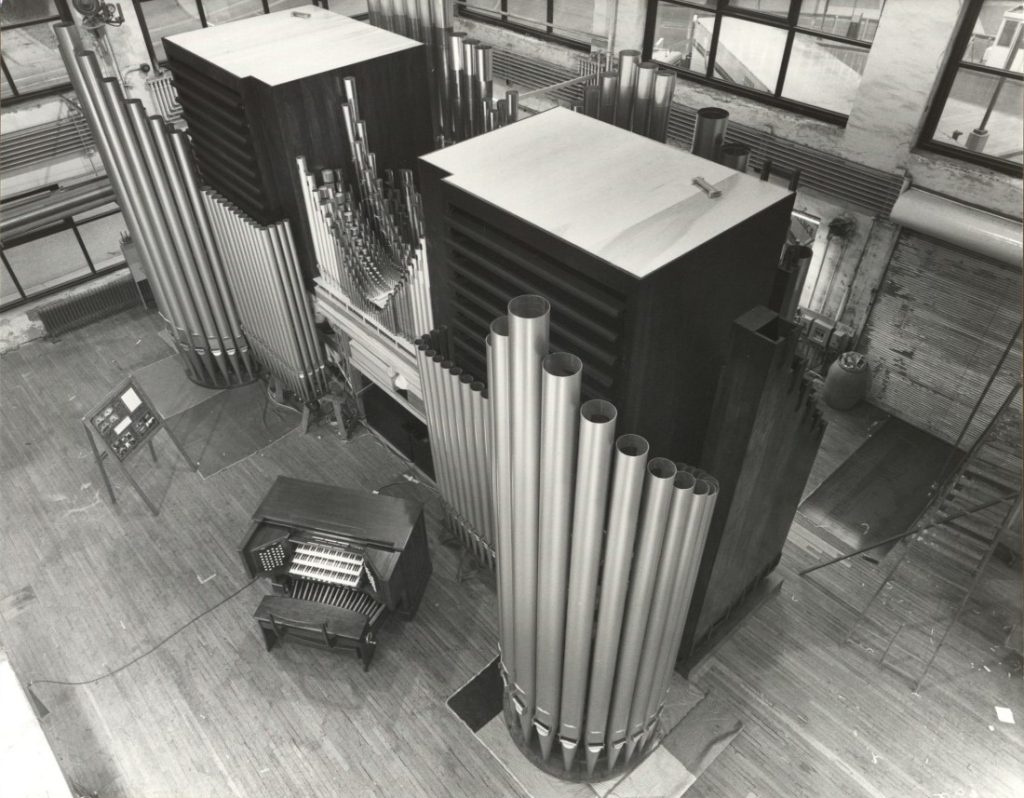

November 14th, 2023While each year we at Spencer process many new collections, we are also adding to preexisting collections through the continued generosity of our donors. From Pulitzer Prize-winning authors to LGBTQIA2S+ activists, an individual’s history doesn’t end when their collection comes through our doors. Individual and organizational histories continue to evolve past the snapshots their historical records provide, and we at Spencer aim to provide as complete a picture as we can! One collection we’d like to draw particular attention to is an addition to the Reuter Organ Company photograph collection (Call Number: RH PH 68). Through this collection, patrons can follow the construction of uniquely hand-crafted pipe organs before they were built into their new homes in institutions all over the world. And now, with a 2023 addition, patrons can see even more of the grandeur of these massive instruments as well as the incredible skill and historical craftsmanship of this Lawrence-based company!

The history of the Reuter Organ Company starts in 1917 when Adolph Reuter established the Reuter-Schwarz Organ Company with his business partner Earl Schwarz. After a disastrous tornado blew through the company factory, the company relocated to the Wilder Brothers Shirt Factory on New Hampshire Street in Lawrence, Kansas, after fulfilling a commission for the city’s Masonic Temple in 1919. Schwarz departed from the company shortly afterwards, and the company was renamed the Reuter Organ Company. In less than ten years, the company grew from a six-employee operation to over 50 full-time employees with over 50 commissions a year. However, after lean years during the Great Depression, the Reuter Organ Company faced a manufacturing ban on musical instruments during World War II and stayed afloat by producing government-sanctioned boxes for munitions materials with a skeletal crew. After the war, the company began to flourish again, and Reuter began hiring skilled staff with formal music education and expertise in organ construction. Through the knowledge base of its staff, the company began to experiment and further develop traditional construction techniques with new pipe organ technology to develop a signature “Reuter sound.”

After Adolph Reuter’s retirement in 1961, the company continued to evolve under the direction of longtime employee Franklin Mitchell. Mitchell, with then newly appointed production manager Albert Neutel, purchased the company in the early 1980s. Together, the two continued to refine the Reuter technical craft, particularly with the mechanical aspects of organ construction and the tonal sound of the company’s organs. After Mitchell’s retirement in 1997, Albert Neutel was joined in management by his son, Albert “J.R.” Neutel, a former longtime employee of the company. Under the Neutel family’s direction, the Reuter Organ Company moved operations from New Hampshire Street to a newly constructed and specially designed factory and administrative facility in northwest Lawrence in 2001. Sixteen years later, the company celebrated its 100th anniversary by holding a public open house in their newer facility and inviting old and new customers alike. By this time, the company had constructed over 2,200 pipe organs for public and private institutions around the world. The company had also built a respected name in organ rehabilitation within the pipe organ community. In 2022, amid the retirement of several longtime key staff members, J.R. Neutel, the company’s current president, decided to sell Reuter’s factory and administrative facility. A major selling point of the Reuter Organ Company is the institutional and craft knowledge of its staff. There is a strong tradition of old staff mentoring new staff and passing down historic pipe organ construction techniques. Operating at the same scale without that same level of institutional knowledge was deemed impossible. And in the beginning of 2023, the Reuter Organ Company further scaled back operations to only fulfilling the customary 11-year warranties offered to their past clients with special consideration for smaller projects.

To honor this historic company and to showcase a new addition to the Reuter Organ Company photograph collection, we here at Spencer have created a temporary exhibit to display images of a few of the beautiful pipe organs Reuter’s has constructed over the years and to dip into some pipe organ terminology. Have you ever wondered were the phrase “pulling out all stops” comes from or just how big the biggest musical instrument in the world can get? Come on by to learn more about this incredible company and the incredible instruments it made! The exhibit opened free to the public in Spencer’s North Gallery on November 1st and will continue to be on display until early January 2024. We hope you “stop” by!

Charissa Pincock

Manuscripts Processor