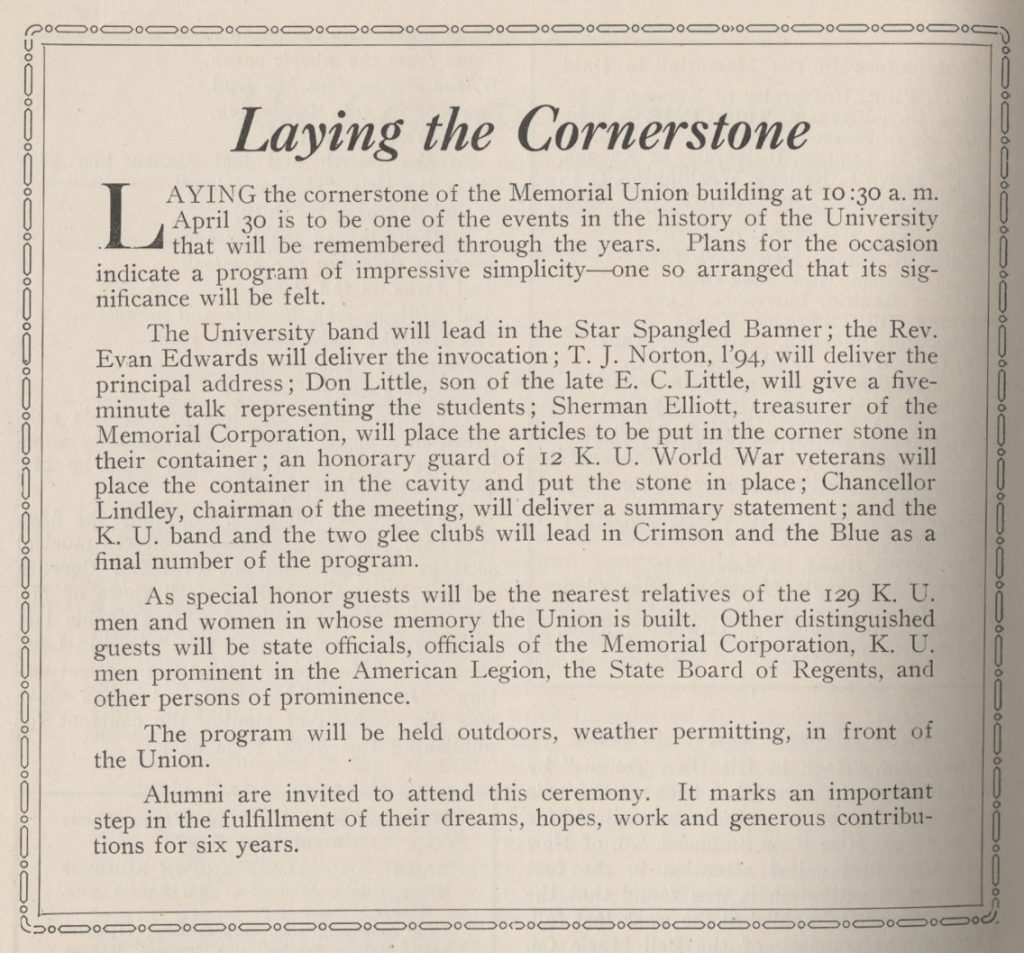

World War I Letters of Forrest W. Bassett: April 30-May 6, 1918

April 30th, 2018In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re going to follow the experiences of one American soldier: nineteen-year-old Forrest W. Bassett, whose letters are held in Spencer’s Kansas Collection. Each Monday we’ll post a new entry, which will feature selected letters from Forrest to thirteen-year-old Ava Marie Shaw from that following week, one hundred years after he wrote them.

Forrest W. Bassett was born in Beloit, Wisconsin, on December 21, 1897 to Daniel F. and Ida V. Bassett. On July 20, 1917 he was sworn into military service at Jefferson Barracks near St. Louis, Missouri. Soon after, he was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for training as a radio operator in Company A of the U. S. Signal Corps’ 6th Field Battalion.

Ava Marie Shaw was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 12, 1903 to Robert and Esther Shaw. Both of Marie’s parents – and her three older siblings – were born in Wisconsin. By 1910 the family was living in Woodstock, Illinois, northwest of Chicago. By 1917 they were in Beloit.

Frequently mentioned in the letters are Forrest’s older half-sister Blanche Treadway (born 1883), who had married Arthur Poquette in 1904, and Marie’s older sister Ethel (born 1896).

Highlights from this week’s letters include a report on muster day (“all Signal troops were inspected by the Colonel; the first time since I’ve been here. It sure was some big doings alright and I wish you could have seen it”) and a thorough explanation of Morse code and telegraphy (“you say you are crazy to learn but I want to caution you that it takes practice with lots of patience – the same as music or anything else”).

Click images to enlarge.

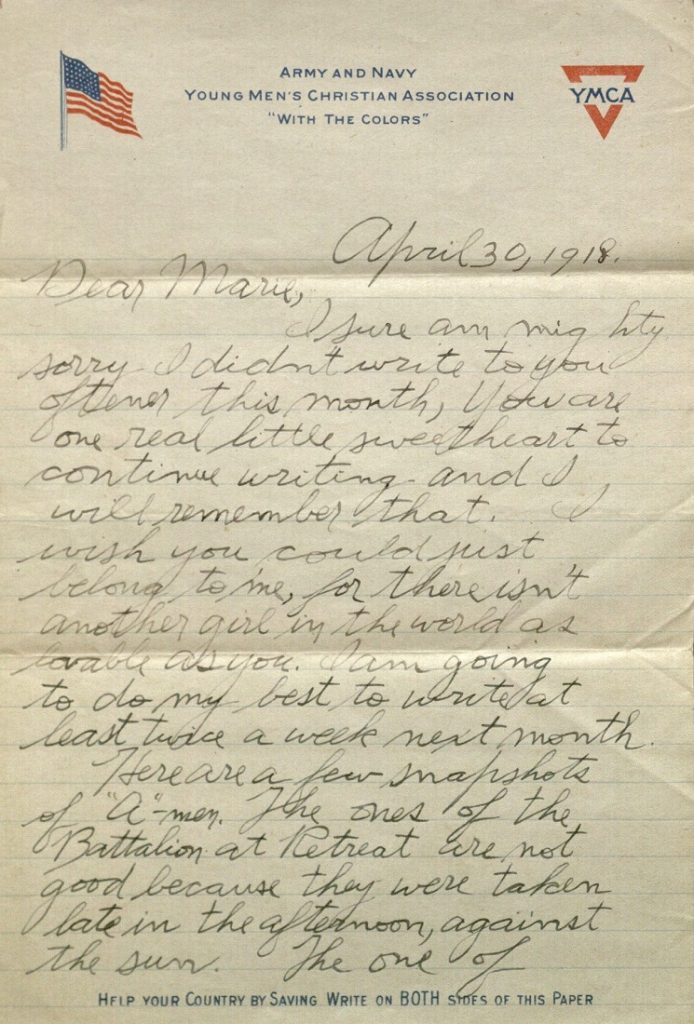

April 30, 1918.

Dear Marie,

I sure am mighty sorry I didn’t write to you oftener this month, You are one real little sweetheart to continue writing and I will remember that. I wish you could just belong to me, for there isn’t another girl in the world as lovable as you. I am going to do my best to write at least twice a week next month.

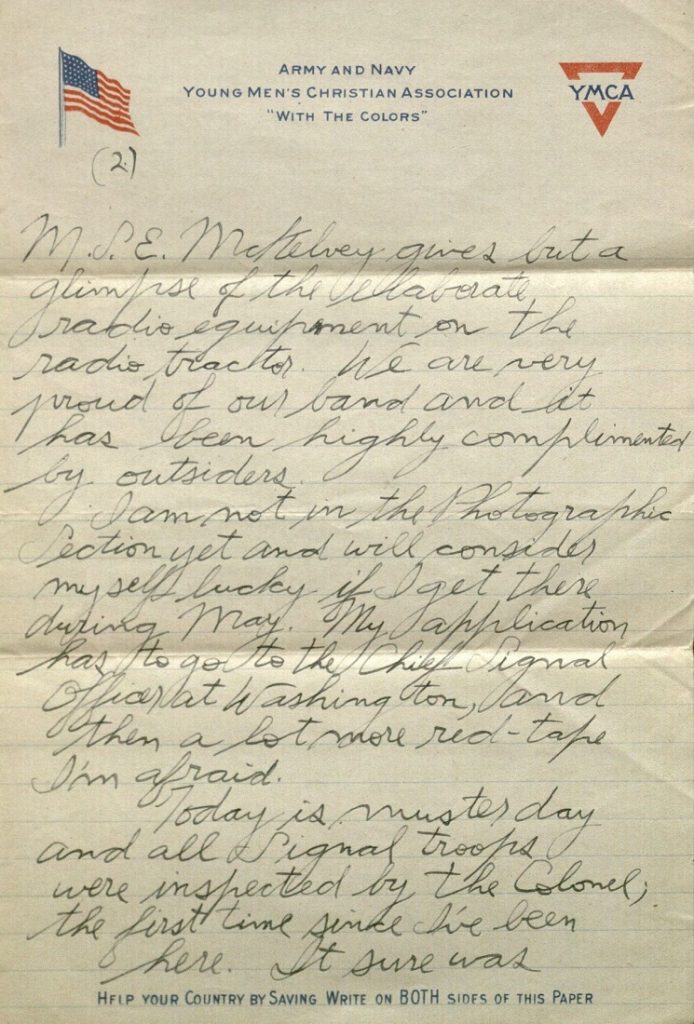

Here are a few snapshots of “A”-men. The ones of the Battalion at Retreat are not good because they were taken late in the afternoon, against the sun. The one of M.S.E. McKelvey gives but a glimpse of the elaborate radio equipment on the radio tractor. We are very proud of our band and it has been highly complimented by outsiders.

I am not in the Photographic Section yet and will consider myself lucky if I get there during May. My application has to go to the Chief Signal Officer at Washington, and then a lot more red-tape I’m afraid.

Today is muster day and all Signal troops were inspected by the Colonel; the first time since I’ve been here. It sure was some big doings alright and I wish you could have seen it.

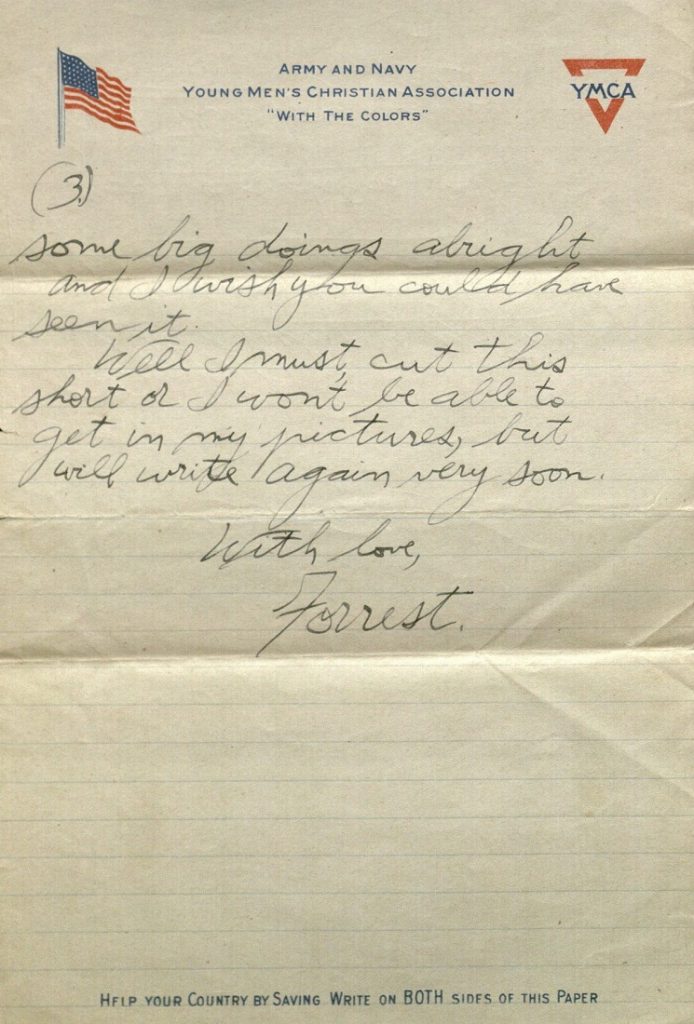

Well I must cut this short or I won’t be able to get in my pictures, but will write again very soon.

With love,

Forrest.

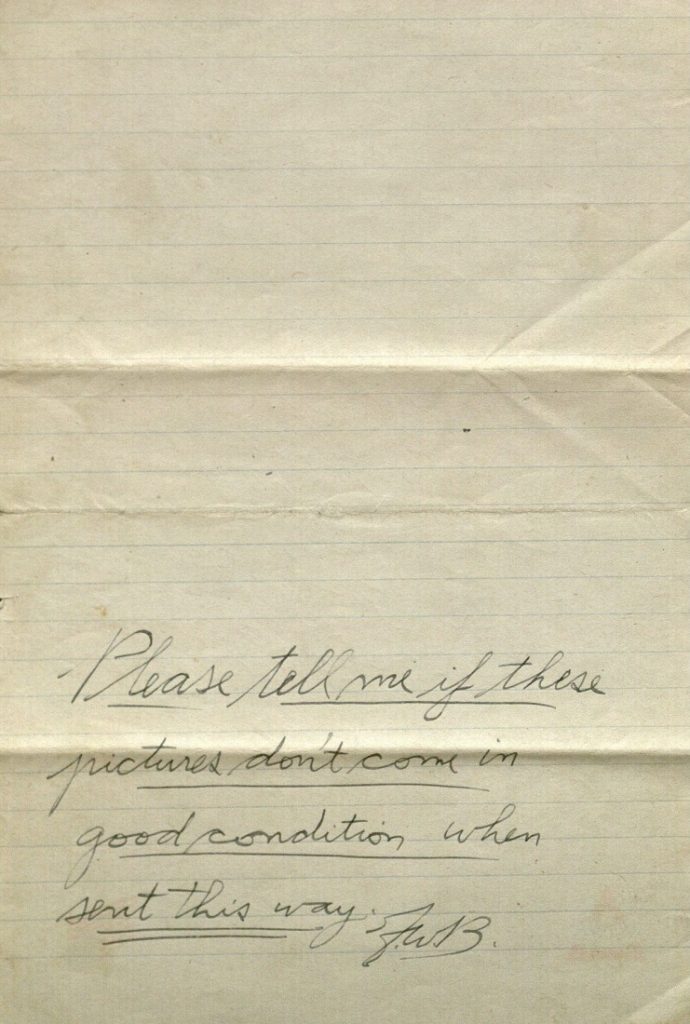

Please tell me if these pictures don’t come in good condition when sent this way. FWB.

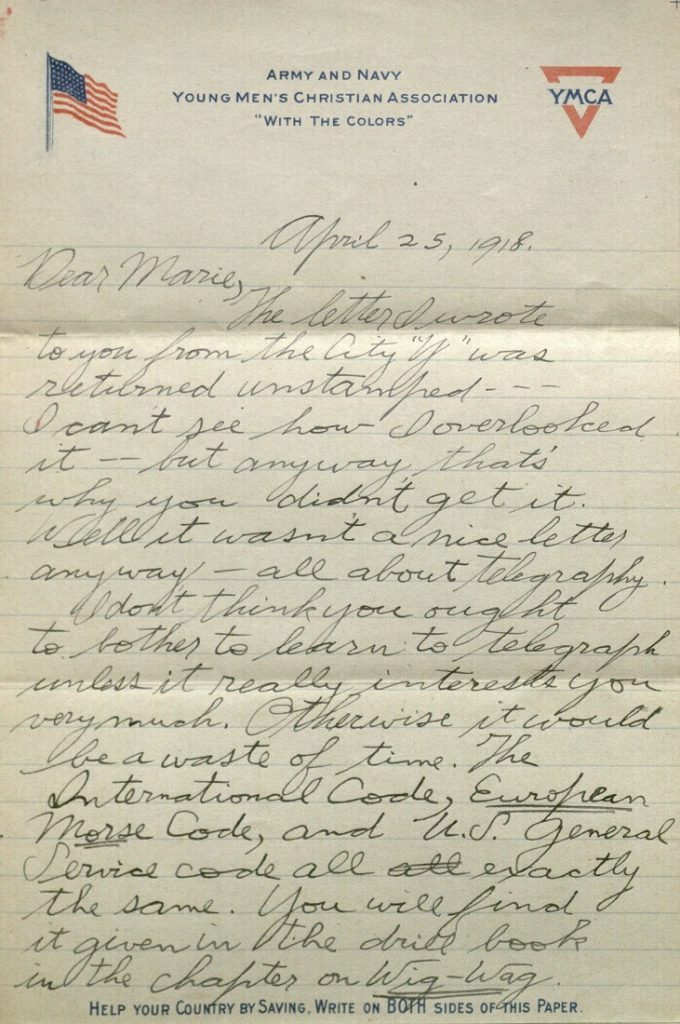

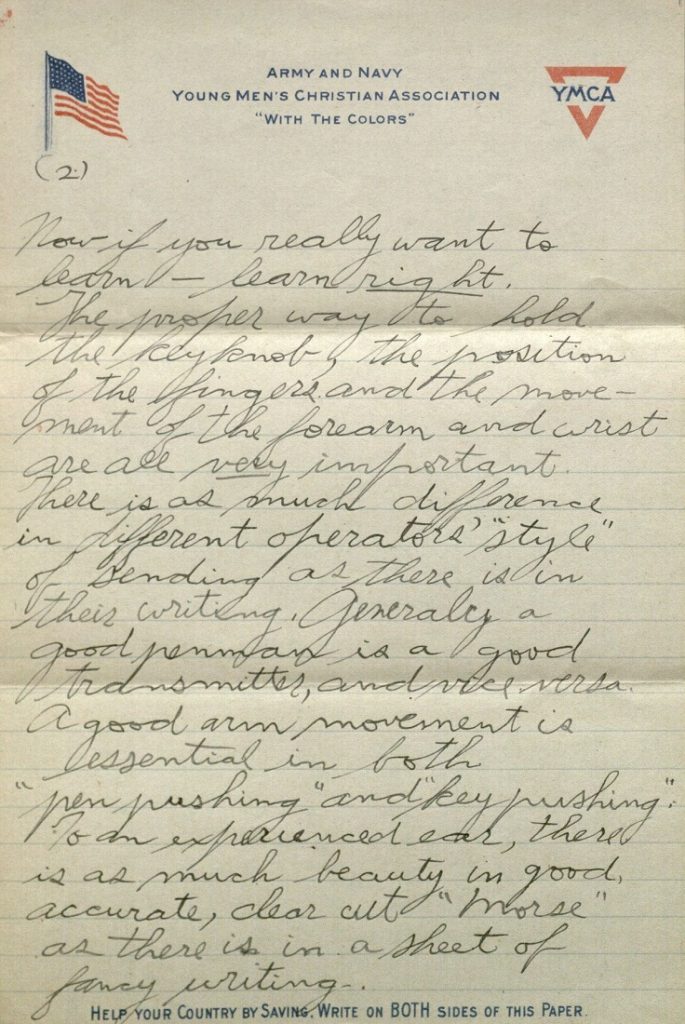

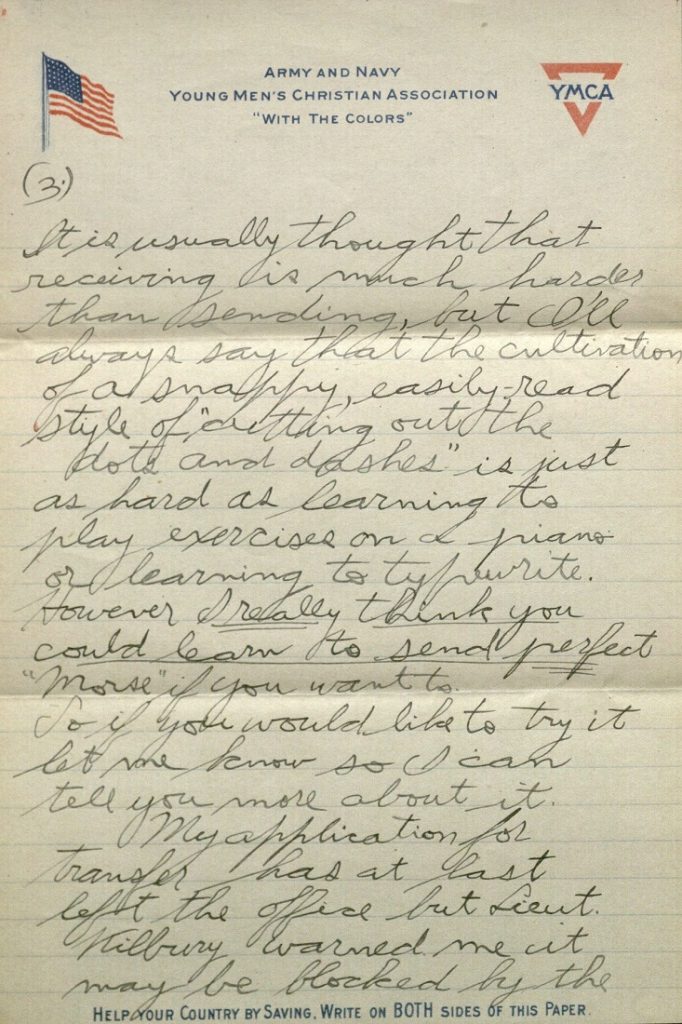

May 3, 1918.

Dear Marie,

The Company has been digging trenches this afternoon and I am a little tired from the snappy pick swinging, so will only write about telegraphy this time. You say you are crazy to learn but I want to caution you that it takes practice with lots of patience – the same as music or anything else. And here is the point:

If you try it at all do your best – not simply to be able to tap the key like some “ham,” but really strive for some degree of perfection. If you don’t want to go at it seriously the same as you do your elocution, do not waste your time – for no time is so utterly wasted as time spent doing a thing half way.

I don’t want to scare you away from learning to telegraph but simply want to warn you not to start something that you haven’t the interest nor enthusiasm to see through.

So think it over and let me know if you want to learn to be as good an operator as the average commercial radio operator. Girl radio amateurs have shown real ability, and right now the government has women teaching telegraphy to Signal Corps recruits.

And again let me say that you have the “stuff” in you to make a first class operator, not a “Morse butcher,” as we call one who chops out the dots and dashes in ragtime.

Telegraphy is similar to playing the piano in that one has to consider “time” and rythm, also one must hold the fingers, wrist and forearm correctly to send well with the key. When you hear the clatter of telegraph instruments in an office, did you ever stop to think that every little combination of dots and dashes forms a letter? Take the word “receive” for instance:

R|E|C|E|I|V|E|

Morse = · ··|·|·· ·|·|··|···-|·

Radio = ·-·|·|-·-·|·|··|···-|·

The American Morse is a little harder to receive because if the letters are run together an R (· ··) can’t be distinguished from EI (·|··) nor a C (·· ·) from IE (··|·) However the European Morse (radio) is better because there are no spaces between parts of one letter. R is (·-·), C is (-·-·), Y is (-·–) instead of (·· ··).

Of course I am taking it for granted that you know what a dot or a dash, or a space is; if you don’t be sure to speak up.

The slightest error in time length of the dots, dashes, and spaces makes one’s best efforts a jumble of unreadable Morse. So you see one must cultivate that sense of time and rythm the same as you do in music. It is easier in telegraphy than in music but at the same time more important

“And” (·-|-·|-··) will sometimes sound like “p’d” (·–·|-··) if it is sent rapidly without proper spacing.

Well you see I am making an awful fuss about accuracy and clearness in transmitting (sending) because anyone with enough practice can read telegraphy at any speed when it is sent properly.

Suppose you were learning to read and write in Greek or any language in which the writing is absolutely different than English. You would first have to learn to draw (not write) each letter, which would be similar to “sending” in radio; and then you would have to learn to recognize each letter, written by another person, which would be similar to “receiving” in radio.

If this is too big a strain on your imagination, then just consider how a 1-B pupil learns to read write.

I am pointing this out to make you see how very simple receiving in radio is.

At first you will think of C as dash, dot, dash, dot (-·-·) but after awhile you will forget the dots and dashes and think of the sound of the combined dots and dashes. For instance when you read you don’t look at each separate letter in a word but you see the whole word at a glance and recognize it without thought of the letters composing it.

I am analyzing these steps in one’s progress in learning telegraphy simply to make you see that it is simply a matter of time and patient practice.

Now for the amount of practice for best results. I wouldn’t advise practising too long at a time – and only when you are “all keyed up” for it. If you feel that you can spare a half an hour or forty minutes each day you will learn fast, and I believe you will like it and find it well worth the effort.

If you decide to try it, I want you to use my telegraph key, as it is a J.H. Bunnell key, which is the best on the market, and is almost “brand new.” Also you may find that sending board of mine useful – do you remember the thing I mean? Well I have a lot more to tell you if you want to go ahead so tell me one way or the other in your next letter.

When you get started, if you do, you will be surprised to find how easy it all is.

Will have to call ten pages enough this time. My next letter will be “nice.”

Forrest.

Meredith Huff

Public Services

Emma Piazza

Public Services Student Assistant