In order to make manuscript collections available to researchers, we have to describe what we have so they know whether it is of interest or not. Typically archival description provides information about what is in the collection itself, as well as some contextual information to aid researchers in understanding more about why materials may be in the collection—a biographical note or administrative history of the creator of the collection, for example, or information about how Spencer acquired the collection. This additional information may come from the collection itself—the creator handily leaves a copy of their resume in their files, or the organization has created annual reports that provide some historical information about them. It can also come from external sources, such as websites and materials the creator and/or donor provided the curator when transferring the collection to Spencer, including notes the curator took when discussing the collection with the donor.

Sometimes, particularly with photographic collections that have little to no textual material donated with them, processing staff have very little to go on when creating a finding aid to help researchers. Take, for example, a collection of cabinet cards and tintypes that had been assembled into a photograph album. These photographic images are beautiful, posed portraits of African Americans in late 19th-century eastern Kansas—but we have very little external information about these images. We’re not even sure how we acquired this collection, or the story behind the creation of the photograph album. If any portrait is identified with a name, it’s hidden on the back, and we haven’t taken the album page package apart, even if the album overall was disbound due to its severe deterioration.

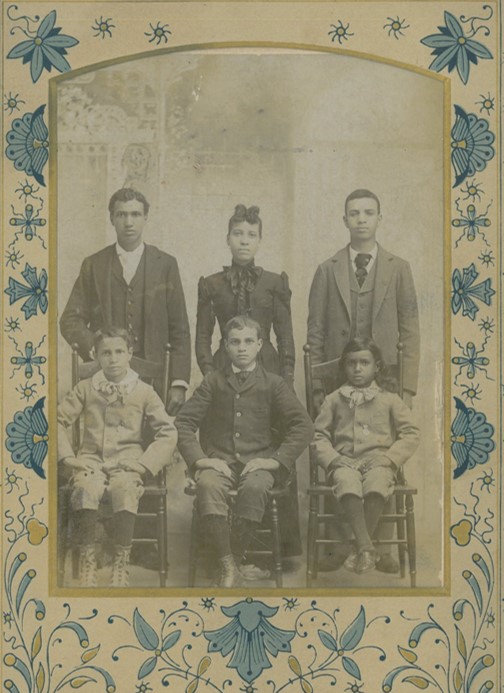

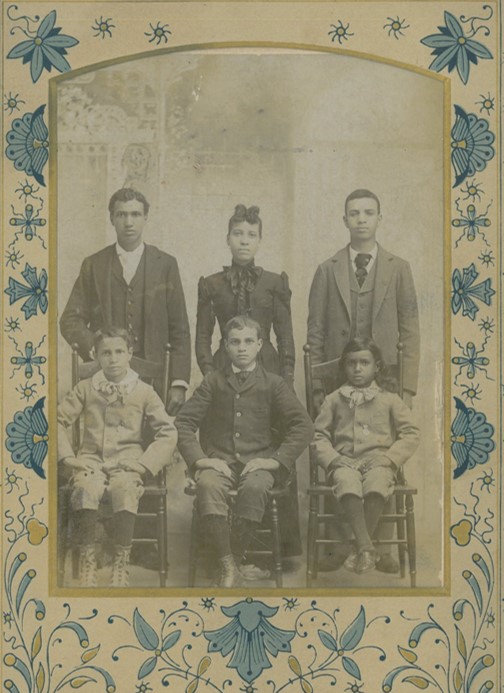

Family group, circa 1890s? African American Photograph Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 531. Click image to enlarge.

In this kind of situation, we provide what information we can. We can describe simply at the collection-level, or we can attempt to describe at the file or individual item level, but those descriptions will necessarily be generic: “Tintype of a soldier in a Civil War-era uniform.”

Tintype of a soldier in a Civil War-era

uniform, circa 1880-1900.

African American Photograph Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 531. Click image to enlarge

We can also provide rough date estimates for when the portraits were made, based upon the clothing worn by the sitters and upon the photographic processes used.

This woman’s overskirt—draped at the back of her dress

helping to create a bustle—tightly-fitted sleeves with cuffs,

and fitted basque-type bodice all indicate her photograph

was probably taken around the mid-1880s. African American Photograph Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 531. Click image to enlarge.

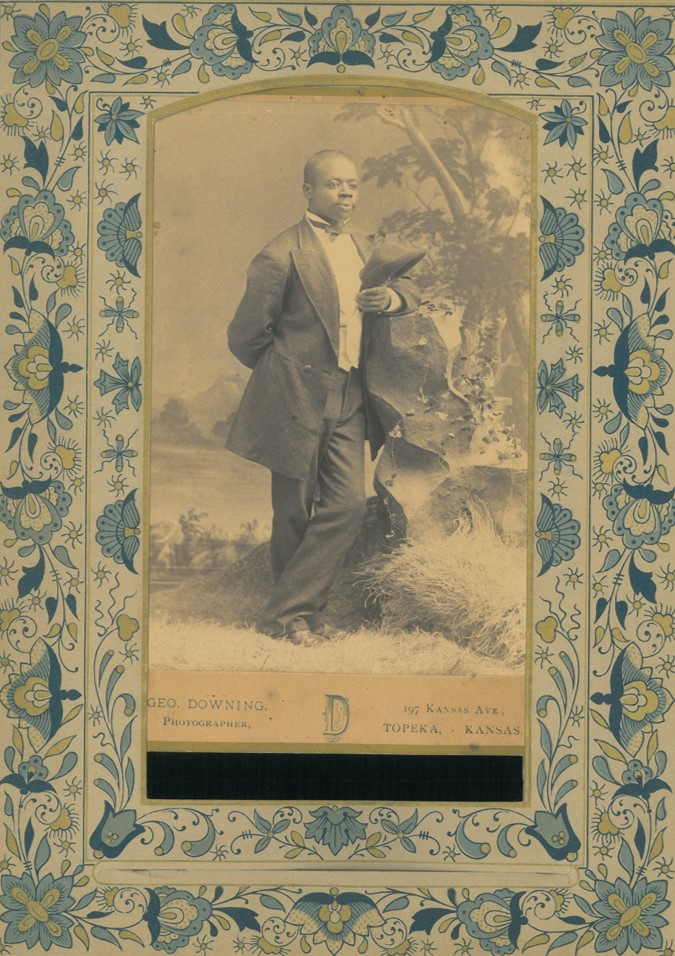

Photographers’ names, often provided on the bottom of cabinet cards and cartes de visite—think about watermarks on professionally-made digital photographs in the 21st century—also provide clues about where and when a collection is from. The photographers found in this collection mostly appear to come from Topeka, Kansas, with some also from Atchison, Lawrence, and perhaps other towns in the eastern part of the state.

The text under the image indicates it was taken by F. F. Mettner,

photographer of Lawrence, Kansas. Also notice the girl’s giant

leg o’mutton sleeves; this style was quite popular in the mid-1890s.

African American Photograph Collection. Call Number: RH PH 531. Click image to enlarge.

There are many decisions that go into processing a collection like this: Do we take apart the individual album pages to see if we can find more identifying information? Do we leave as is because this was how the images were intended to be seen (and who knows if anybody wrote anything on the back anyway)? Do we describe at a detailed level when we cannot provide names, or are we content with providing a simple collection-level description and hope that researchers are able to realize there may be a treasure trove from that collective description?

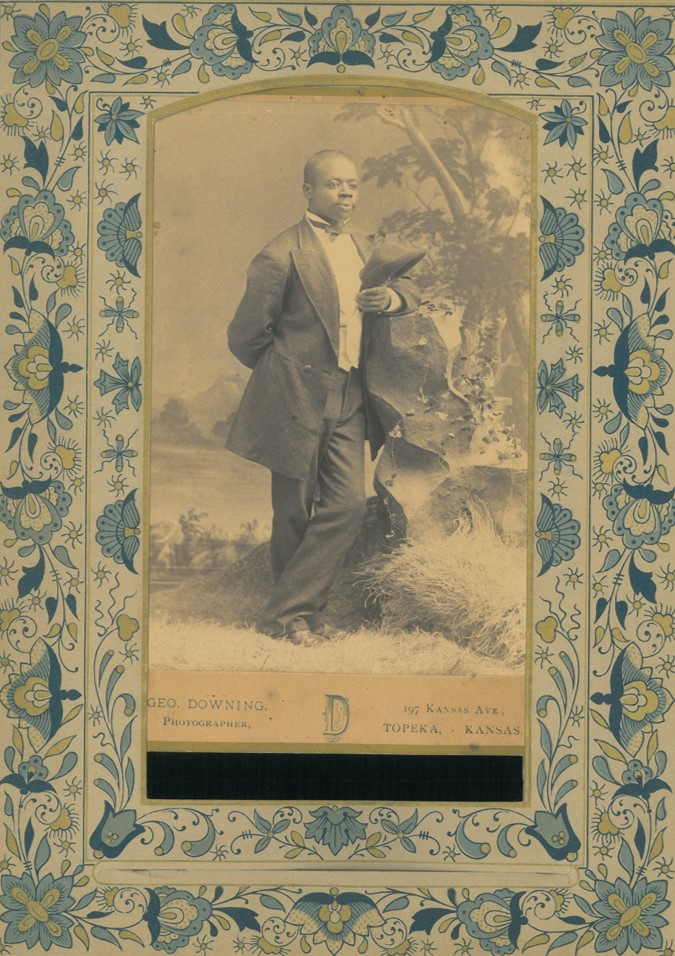

Who is this gentleman? If we knew his name,

what other information could it provide?

African American Photograph Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 531. Click image to enlarge.

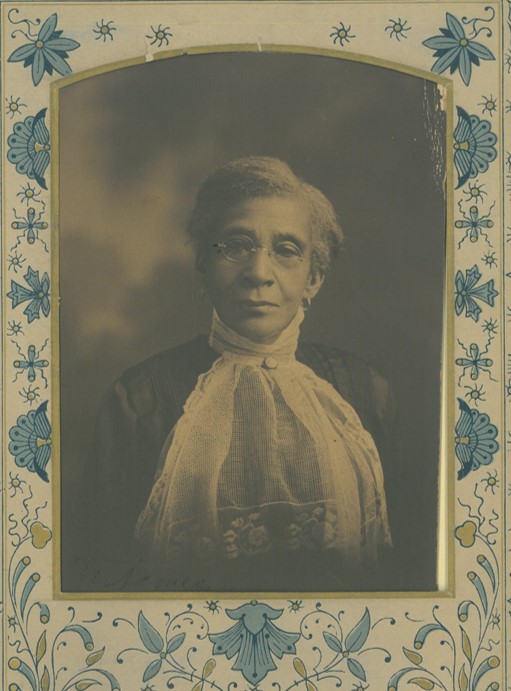

No matter what we choose to do, archival description cannot capture the beauty of the women’s and children’s dresses and men’s suits—the sitters no doubt wearing their Sunday finest—the personalities that peek through even these stiffly posed studio portraits, the stories that may be hiding in the pictures themselves.

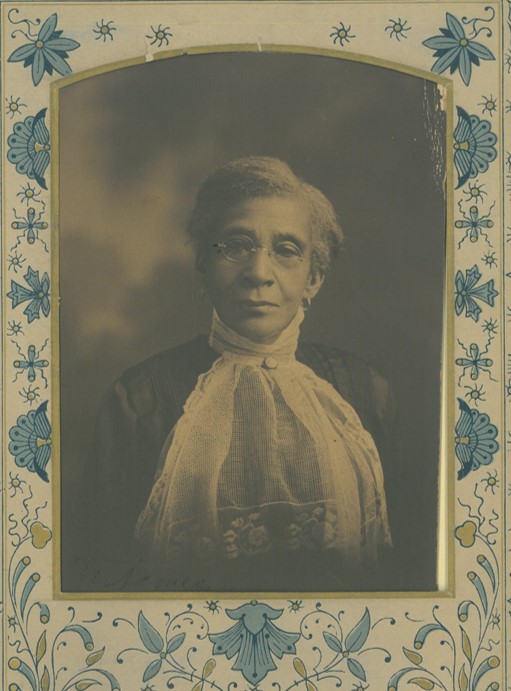

Portrait of an unknown woman, circa 1880-1900.

Marcella is especially fond of this photograph.

African American Photograph Collection.

Call Number: RH PH 531. Click image to enlarge.

If you have any information about any of these images, or others in the collection, we would be happy to add that information to the finding aid. To request to use the collection, contact Public Services staff at ksrlref@ku.edu. To provide more information about the collection, please also contact our African American Experience field archivist, Deborah Dandridge, at ddandrid@ku.edu.

Marcella Huggard

Manuscript Processing Coordinator