The Pelican in Her Piety

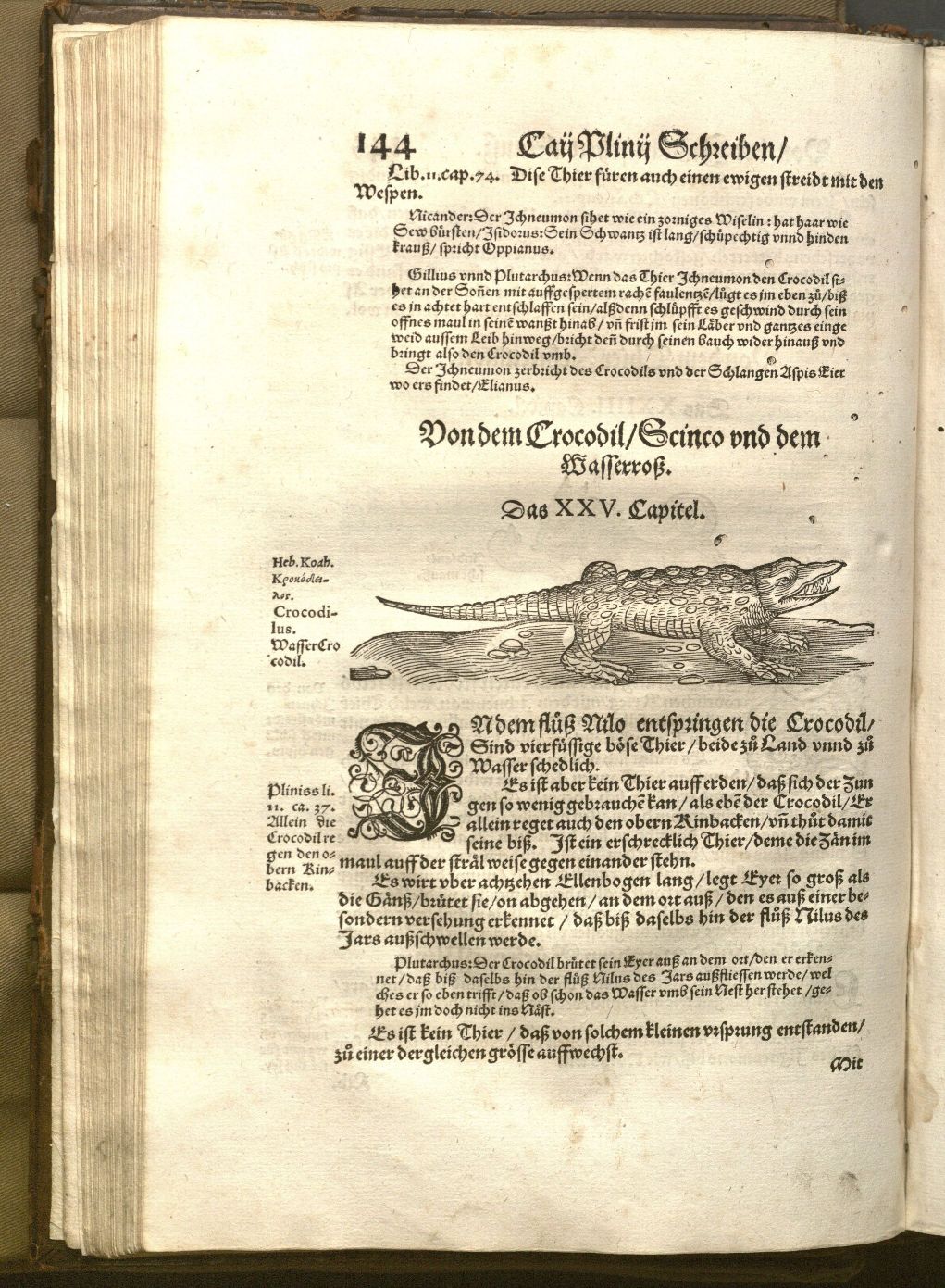

July 24th, 2017Just a few months after I began working at Kenneth Spencer Research Library, Dr. Elspeth Healey, one of our Special Collections librarians, showed me some materials she had pulled for a class on Renaissance printmaking. With my background in Medieval and Renaissance art history, I was excited to explore the materials she had selected. She drew my attention to a small image in Conrad Gessner’s Historiae Animalium, a sixteenth-century natural history tome featuring various bird species. The somewhat bizarre and gruesome image in question shows a pelican pecking at its breast with visible blood spilling on a nest of baby birds – a startling depiction but one familiar to me from medieval bestiaries. The rather macabre bird depicted was none other than a vulning or heraldic pelican.

A vulning pelican in Historia animalium by Conrad Gessner, 1555.

Call Number: Ellis Aves G97. Click image to enlarge.

The term vulning comes from the Latin verb “vulno” which means “to wound.” When pelicans feed their young, the mother macerates fish in the large sack in her beak then feeds it to her babies by lowering her beak to her chest to transfer the regurgitated fish more easily. The observation of this feeding practice led to the mistaken descriptions of female pelicans pecking their breasts and spilling blood onto their babies to provide sustenance. The idea of a pelican wounding herself for the sake of her young gained a religious connotation and became a symbol for Jesus Christ and his sacrificial death and resurrection – a necessary sacrifice for the redemption of humanity according to the Christian tradition. Also described as a “pelican in her piety,” the vulning pelican became a popular symbol in medieval heraldry and was featured in bestiaries (books about a mixture of real and imaginary animals) because of this religious association.

The presence of the vulning pelican in bestiaries could explains how this popular piece of religious symbolism found its way into a scientific study from the sixteenth century. Bestiaries were collections of descriptions of both real and mythological beasts. These creatures were typically accompanied by some moral tale that was meant to be instructional for the reader. While bestiaries had been around for centuries, they gained a high level of popularity during the Middle Ages. These bestiaries were in some ways the forerunners to later scientific publications like Conrad Gessner’s book about the natural history of animals. It is not surprising that certain illustrations were carried over from the bestiaries into early scientific books during the transition from the Medieval to the Renaissance period.

However, the vulning pelican also appeared in emblem books, a type of book that originated in Italy in the mid-sixteenth century, rapidly became fashionable throughout Europe, and remained popular until the early eighteenth century. An emblem book consists of a series of pictures, each accompanied by a motto and an explanatory poem, which together present a concept, usually with a moral, about a theme, such as religion, politics, or love. The vulning pelican appears in emblem books with a religious theme. This continuing popularity via another source could also account for the vulning pelican imagery’s use in naturalist texts.

The appropriation of the vulning pelican from religious symbol to scientific illustration has helped preserve the history of this strange depiction. Considering the vulning pelican’s history as a symbol of the Christian resurrection, it is rather ironic to see how this depiction has experienced a resurrection of its own throughout the centuries.

Emily Beran

Public Services