Myrtle Shane: Devoted Ally of the Armenian People

April 24th, 2017“I shall stay here and face starvation with the Armenians.” Myrtle Shane, 1920

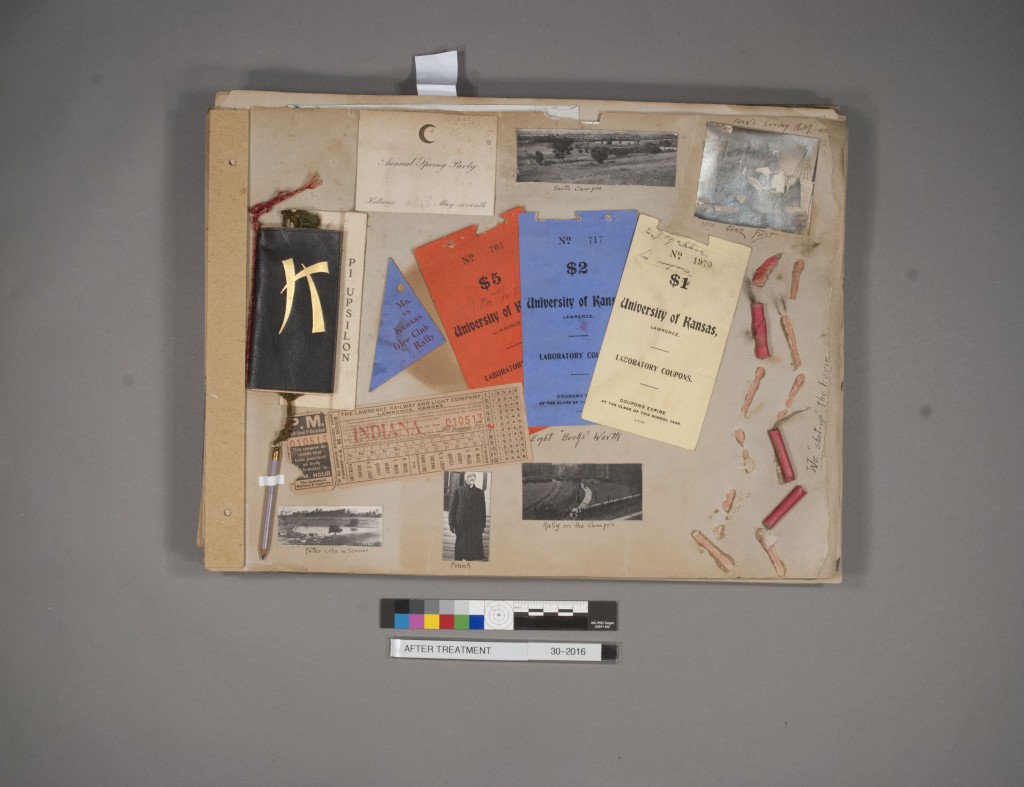

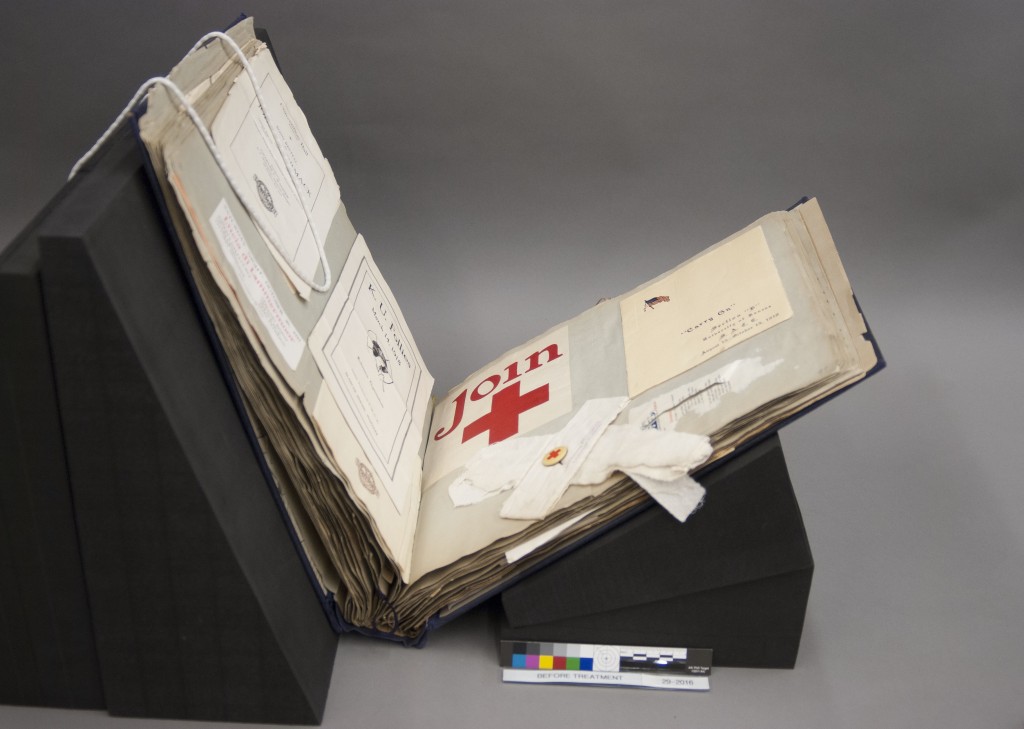

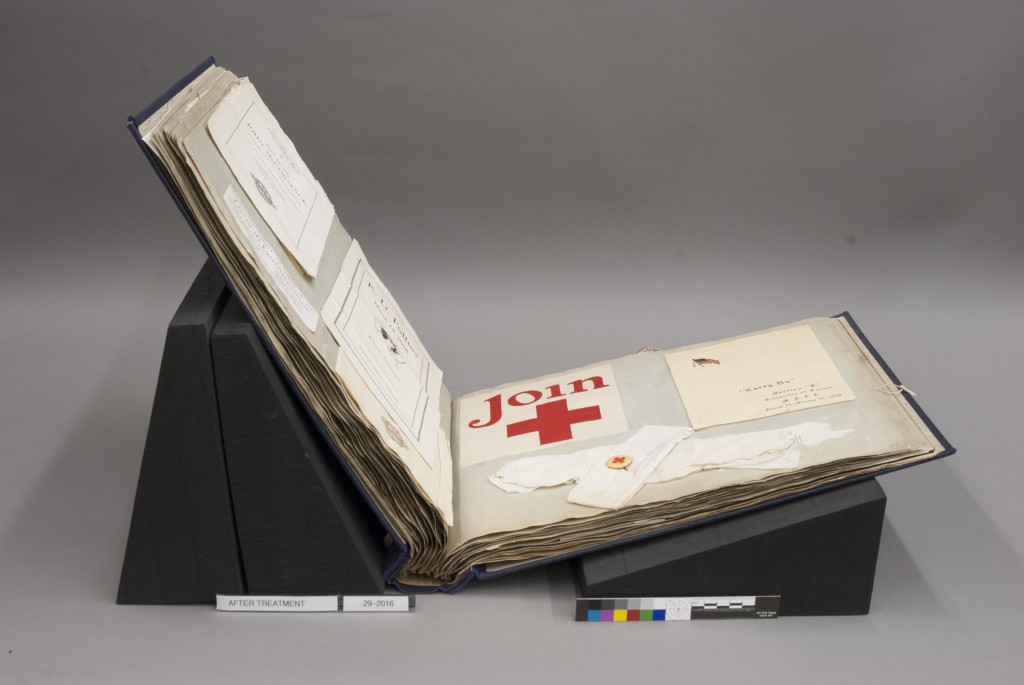

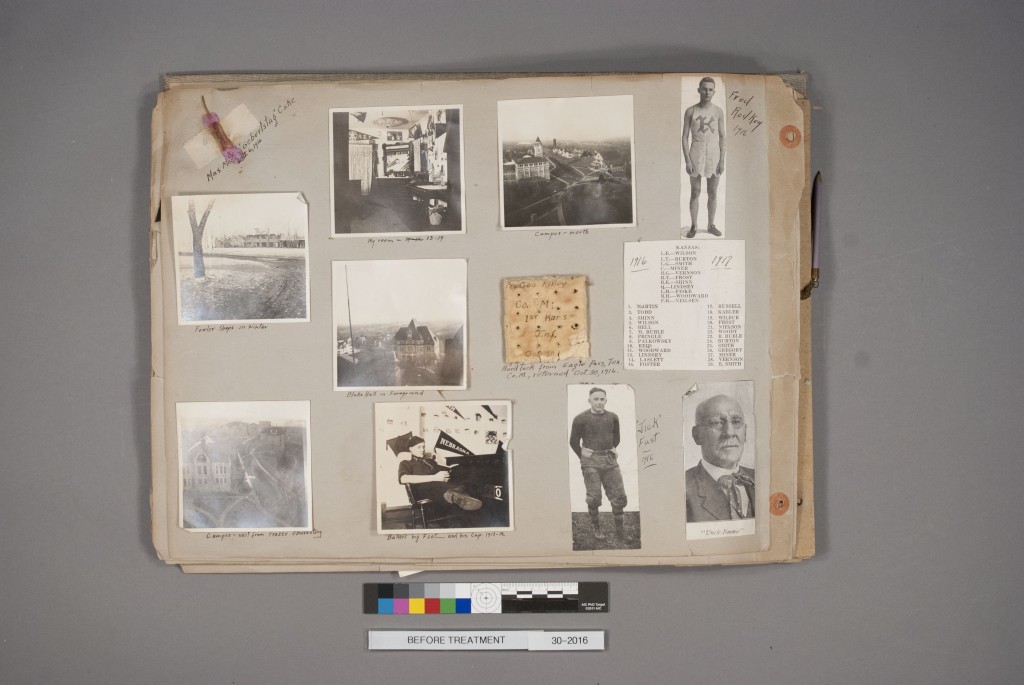

One of the rewards of working in a place like Spencer Research Library are the unexpected discoveries you make. While working on a project involving the Shane-Thompson Collection, I came across the courageous story of one of James Shane’s daughters, Myrtle Shane. Her story is especially fitting on April 24th, Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day.

Photograph of Myrtle O. Shane, undated.

Shane-Thompson Collection, Kansas Collection.

Call number: RH PH 500:2.18. Click image to enlarge.

War always brings with it atrocities, and World War I was certainly no exception. One of the greatest atrocities during that time was the government-sponsored genocide and deportation of the Armenian people, which took place between 1915 and the early 1920s. The Armenian people were Christians who had made their home in the Caucasus region of Eurasia since the 6th century BC. Control of Armenia shifted between empires, eventually becoming part of the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. The Ottoman leaders and their subjects were Muslim, yet, in spite of this vast religious difference, the two groups were able to live together relatively peacefully. Still, the majority of Muslims viewed the Armenians as “infidels” and subjected them to unequal laws and unfair treatment. Toward the end of the 19th century the Ottoman Empire began to fall apart, and there was growing suspicion among the Muslim rulers that, if given the opportunity, the Armenians would be loyal to Christian governments such as Russia, and that they would turn on their Muslim compatriots. Consequently, in 1894 Ottoman ruler Abdul Hamid II instigated the first of several pogroms against the Armenians, ordering the razing of their villages and the massacre of the people.

In 1914, Turkey entered World War I on the side of the Germans and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and at the same time the Ottoman religious authorities declared a holy war against all Christians. The view they held of the Armenian people as infidels and potential traitors was intensified, and now it included Turkish military leaders. The genocide began on April 24, 1915, when the Turkish government started killing and deporting Armenian citizens. At the start of the war there were an estimated two million Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire. Between 1915 and 1923 it is believed that over one and a half million of them died by execution, starvation, exhaustion, or disease. There were many non-Armenian witnesses to the genocide, in spite of government imposed restrictions and censorship of photography and reporting. Foreign diplomats and missionaries gave chilling accounts of the atrocities taking place. Among the missionaries serving in Turkey in 1915 was a woman named Myrtle Shane.

Myrtle was born in Lawrence, Kansas, on August 16, 1880, the seventh of ten children born to James and Missouri Lee Shane. Myrtle graduated from the University of Kansas in 1906 and taught school for nearly eight years. In 1913, at the age of 32, she turned her attention to the mission field and joined the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Her first assignment was to the mission in Bitlis, Turkey, where she was serving when World War I broke out and the full-scale genocide pogrom began.

Certificate of Registration of American Citizenry

for Myrtle O. Shane, 1913.

Accessed via Ancestry.com. Click image to enlarge.

By June 1915 the crisis had reached Bitlis, and the Armenian people began to seek refuge in the mission. Myrtle and a handful of other missionaries took it upon themselves to give the refugees as much protection as possible. They did this at great risk because foreigners had been forbidden to offer any help whatsoever. Not conceding to this directive, Myrtle went to the local governor to ask if he would allow the refugees – by this time about sixty women and children – to remain with her at the mission. She was told no, that there were to be no Armenians left in Bitlis. “In that case I will not give them up,” she replied. After several attempts by Myrtle, the governor finally relented and agreed to leave the refugees at the mission as long as he could.

By the middle of July conditions had worsened in Bitlis, and all missionaries were ordered by the governor to leave because he could no longer guarantee their safety, but again, Myrtle and her colleagues refused to go. Eventually Myrtle was the only missionary left to supervise the mission and the refugees. The others had died of typhus (which Myrtle also contracted during this time), been forced to leave because they were men, or been reassigned to positions in other besieged Armenian communities. Several times throughout the summer and fall attempts were made to wrest the refugees from the mission, but Myrtle always managed to negotiate a way to keep them.

By November, though, Myrtle herself was finally forced by the American State Department to leave Bitlis and go to Harpoot, where it was safer for her. She fought the order as long as she could and went reluctantly. She worked in Harpoot until the summer of 1917, when diplomatic relations between the United States and Turkey were severed and Americans were ordered to leave for good. Myrtle returned to the United States in October 1917. With no one left to defend them, the refugees were eventually overtaken. While back home, Myrtle went on a speaking tour and told her audiences what she had witnessed, encouraging Americans to provide support for the suffering Armenian people.

Letter from the State Department to

Herbert Thompson, Myrtle’s brother-in-law, 1915.

Shane Thompson Collection, Kansas Collection.

Call number: RH MS 58:1.12. Click image to enlarge.

An account of a lecture given by Myrtle Shane

about the “cruelties to [the] Armenian Race,”

Lawrence Journal-World, January 3, 1918.

Click image to enlarge.

In 1919, at the closing of World War I, Myrtle returned to Turkey, having joined the first expedition of the American Commission for Relief in the Near East, an organization formed to provide humanitarian aid in response to the Armenian Genocide. She worked as the director of an orphanage in Alexandropol, housing nearly 5,000 orphans. Ten of her assistants were women she had protected in Bitlis. The post-war Treaty of Sevres established an Armenian state, but the new Turkish regime did not recognize it and soon atrocities against the Armenian people resumed. Again, Myrtle fought to stay with her charges until the tension eased, resisting orders to leave and dedicating herself to defend the people she had come to love. She went on to serve in Turkey, as well as in Greece and Beirut, for another ten years. She retired from the Commission in 1929. Upon her return to the United States, she went to live with her sister, Ella Gilbert, in Columbus, Ohio, and resumed teaching school. On June 28, 1953, Myrtle suffered a stroke and passed away at age 72.

Sources

Armenian National Institute, Washington, DC.

Digital Library for International Research.

Hubbard, Ethel Daniels. Lone Sentinels in the Near East: War Stories of American Women in Turkey and Serbia. Boston: Woman’s Board of Missions, 1920.

Knapp, Grace Higley. The Tragedy of Bitlis. New York and Chicago: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1919. Available through KU Libraries.

Shane-Thompson Collection, RH MS 58 and RH PH 500, Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services