Coffee Cake and Catsup: A Brief Overview and Contextualization of the Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book

September 16th, 2025This is the first in a short series of posts highlighting students’ projects from Laura Mielke’s Spring 2025 class, “Archives in Scholarship” (ENGL 776). This week’s post was written by Joohye Oh, who graduated from KU in 2025 with a B.A. in English and Spanish. Her research interests include foodways and literacy.

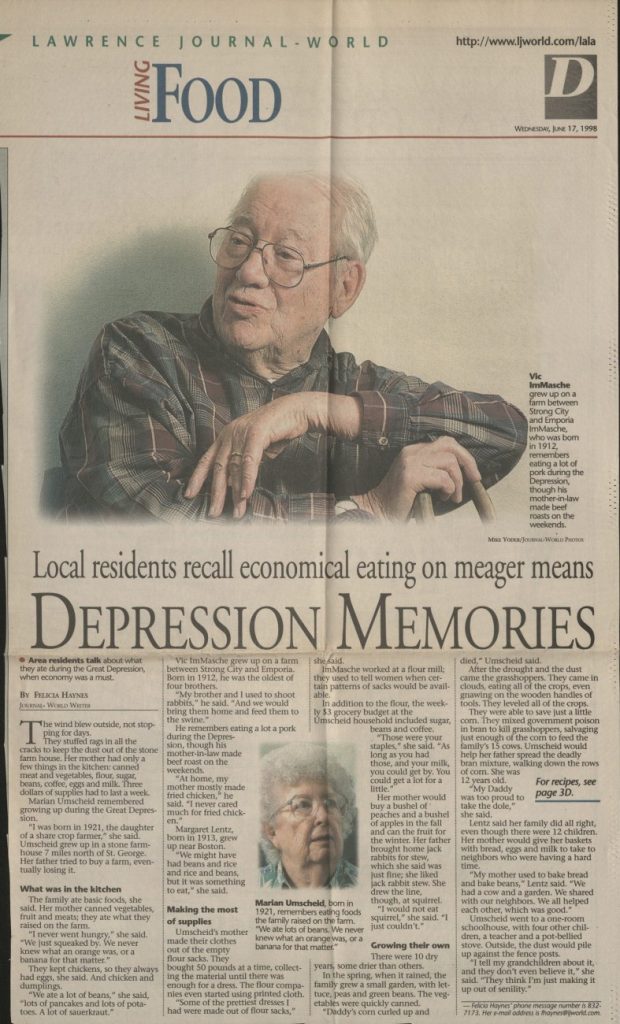

Cookbooks – especially historic ones – are fascinating texts. Unlike 21st-century cookbooks that feature pictures of recipes, touching or interesting narrative asides, and use of less commonly found ingredients, older American cookbooks prioritize presenting readers and users with a no-frills approach to cooking. These cookbooks tend to be text-heavy and use ingredients more likely found in a pantry than a gourmet grocer. A wonderful example of an intriguing historical cookbook is the Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book, published in 1894, which showcases a slice of late 19th-century American foodways and the culinary literacy of the organized and ambitious women of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Parsons, Kansas. (“Fin de siècle” is a French term meaning “end of century.”)

Left: The protective red board cover for the Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book, which is a library-created pamphlet binding. Right: The cookbook’s original cover, slightly deteriorating, with the full title. Call Number: RH B2788. Click images to enlarge.

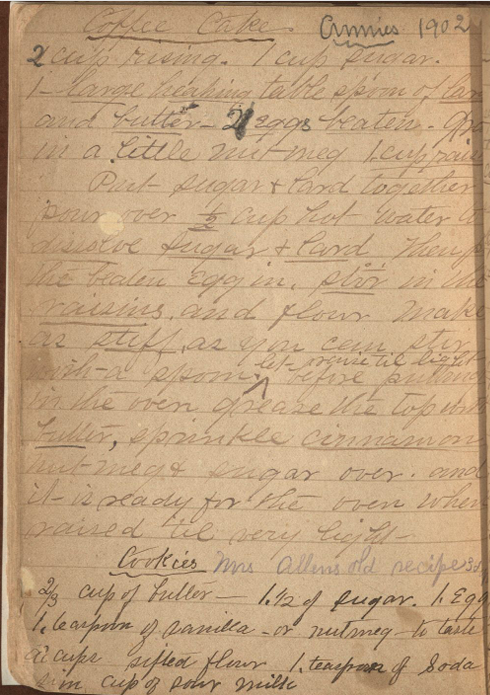

The Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book consists of two sections. First, there are 58 printed pages that include tipped-in clippings from magazines. Second, in the back, there are 11 pages of faintly lined paper that Whitney Baker, Head of Conservation Services at KU Libraries, believes were bound with the original publication and printed section. Someone, presumably a woman, filled with the blank lined pages with handwritten recipes that she selected and compiled. Instead of being completely different from the printed section, I see the handwritten section as extending the themes of women’s authorship and community while offering contemporary researchers a closer look at earlier American foodways in relation to the genre of the cookbook and literacy practices.

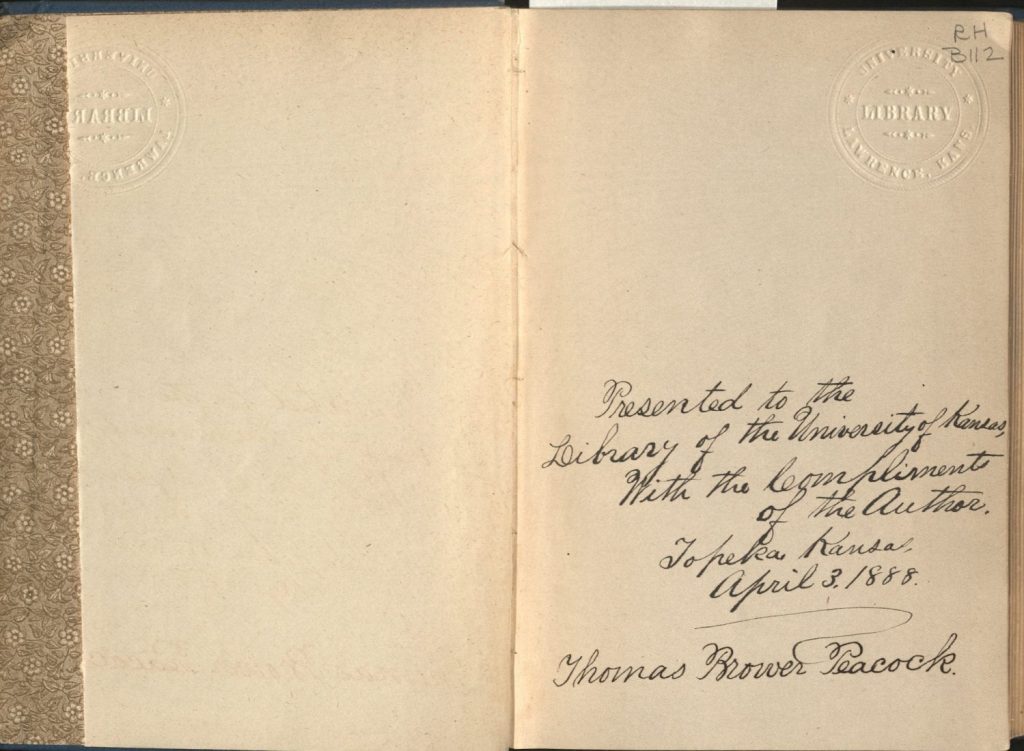

Women’s authorship is especially central to this object. Writing this cookbook arguably opened up new avenues for authorship and empowerment for the Parsons women, like the way literary clubs did for middle-class Black women in the 1890s, as African American literature and literary studies scholar Elizabeth McHenry shows (120). Additionally, the place of authorship for both groups reflects the importance of a shared community space: a church for the Parsons women and a literary club member’s home for the Black women. One can imagine how these women – positioned as authors – selected, arranged, edited, and published these recipes (texts). This model of authorship furthers the legacy of women as authors in the cookbook genre. In fact, several of the earliest known American cookbooks – like The Virginia Housewife by Mary Randolph (1824), a text that showcases the elaborate culinary repertoire of the Southern elite (Fisher 19) – are powerful texts by knowledgeable women, two characteristics also found in the handwritten portion of the Fin-de-Siècle cookbook.

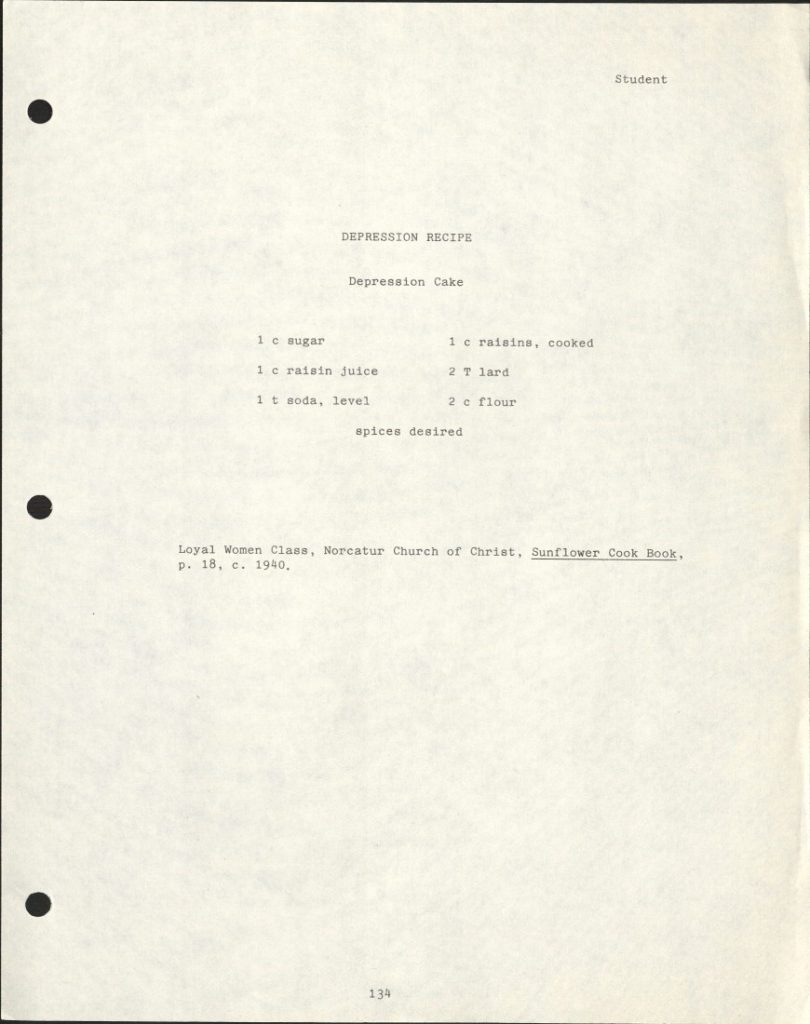

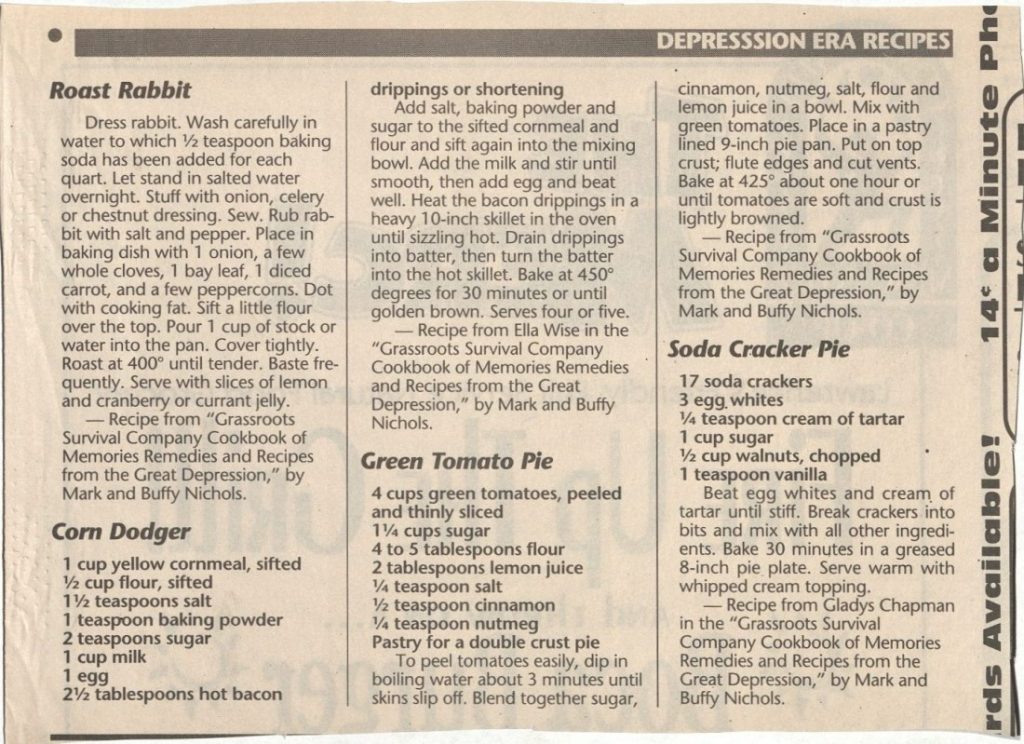

Community as an essential part of learning to read and write can also be inferred from the processes related to producing this text; in other words, these “[community] cookbooks function as literate practices of a community, sponsored by the community members who were themselves cooks, contributors, readers, organizers and editors” (Mastrangelo 73). Indeed, physical traces of this can be seen via each recipe’s attribution to a specific woman as well as the broader fact that the women in Parsons were using their social and technical skills to engage in readerly and writerly practices tied to their growing culinary literacy. To write a cohesive cookbook, they would have had to learn the characteristics of the cookbook genre as well as its subgenres like recipes and instructions. The clear grasp of these characteristics and deft culinary knowledge is present in the neat organization of the cookbook and mirrored in the handwritten recipes which give specific unit measurements for ingredients and reflect a strong awareness of effective kitchen habits. The writer of the handwritten portion continues the practice of attributing specific recipes to specific women: for example, the “Tomatoes Pickles” recipe is attributed to Mrs. Dean while the “Coffee Cake” recipe, found a few pages later, is attributed to “Annie.”

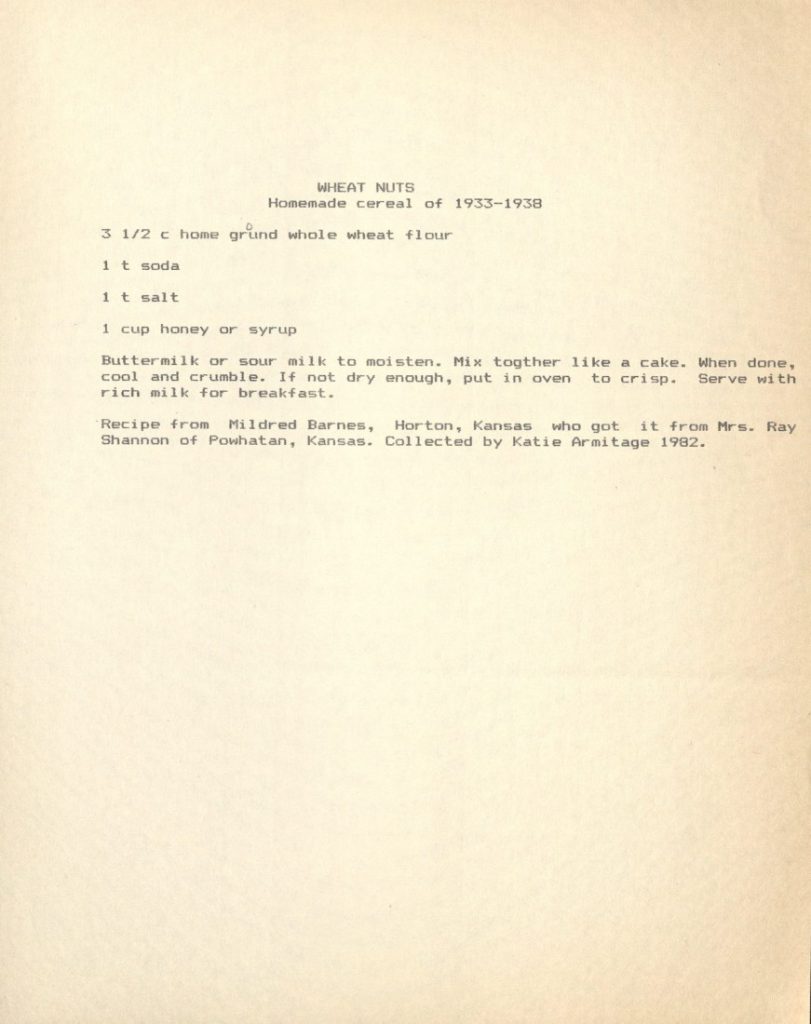

The diversity of recipes in the second (handwritten) section hints at the importance of homemade food in the 19th century. Specifically, as someone whose culinary practices are greatly influenced by 21st-century food systems (easy availability of ingredients, prepared foods, and new food media) it is a little surprising at times to see recipes like “Good Tomato Catsup” and the instructions for mayonnaise/aioli in a “Salad” because these are two products I associate more closely with Heinz and Hellman’s. The appearance of these two condiments seems to reflect the different food practices for a woman and her household in Parsons before the advent of supermarkets and easy availability of industrial food items.

Together, the first and second parts of the Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book offer a small glimpse into the complex and vibrant American foodways of the late 19th century and their broader historical and cultural contexts. The handwritten recipes carefully capture the specialized knowledge, skills, and dedication that the woman compiler most likely possessed while also reinforcing the idea that community and gendered authorship exist in a text often overlooked as simply being a collection of memories or a collection of delightful eating. Cookbooks and recipes, just like the small handwritten portion at the back of the Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book, are masterful representations of how literacy exists in the spaces and places sometimes overlooked because of who we consider to be authors and what we consider to be literature – even if that literature is mostly pickled green tomatoes recipes.

Joohye Oh

ENGL 776 student, Spring 2025

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Elspeth Healey, Phil Cunningham, Caitlin Klepper, Whitney Baker, and Shelby Schellenger at Spencer Research Library; English 776 peers; Professor Laura Mielke; and the ladies of Parsons who compiled this cookbook.

Works Cited

Baker, Whitney. “Re: Parsons cookbook.” Email received by Joohye Oh and Caitlin Klepper, 24 April 2025.

Fisher, Carol. The American Cookbook: A History. McFarland, 2006 (Call Number: X715 .F534 2006).

Mastrangelo, Lisa. “Community Cookbooks: Sponsors of Literacy and Community Identity.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, 2015, pp. 73–86.

McHenry, Elizabeth. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies. Duke University Press, 2002 (Call Number: PS153.N5 M36 2002).

St. John’s Episcopal Church. Fin-de-Siècle Cook Book. Parsons, Kansas, 1894 (Call Number: RH B2788).