Pulitzer Pride: Gwendolyn Brooks in the Kansas Collection

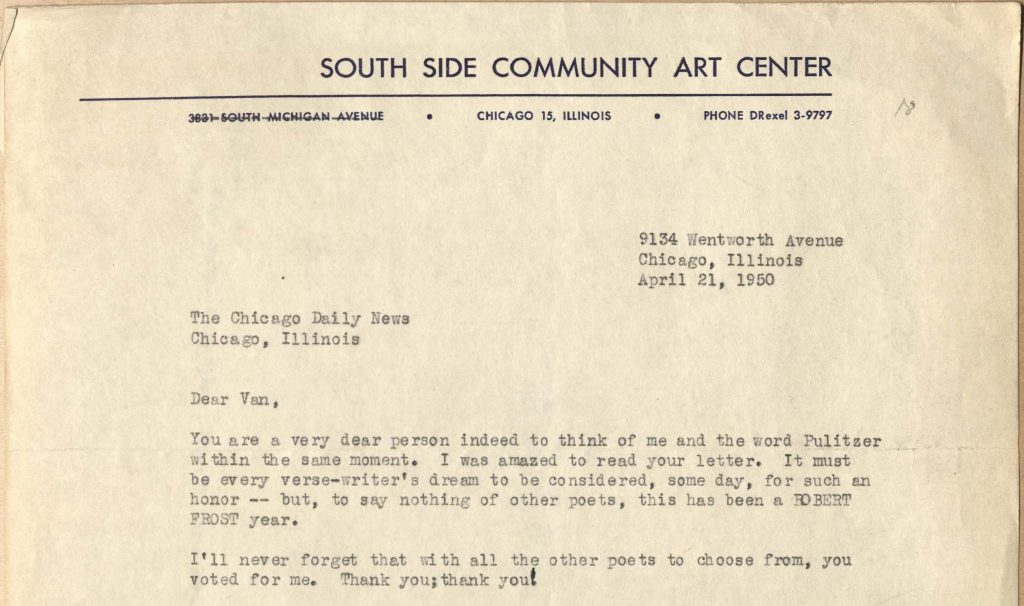

April 8th, 2020You are a very dear person indeed to think of me and the word Pulitzer within the same moment. I was amazed to read your letter. It must be every verse-writer’s dream to be considered, some day, for such an honor – but, to say nothing of other poets, this has been a ROBERT FROST year.

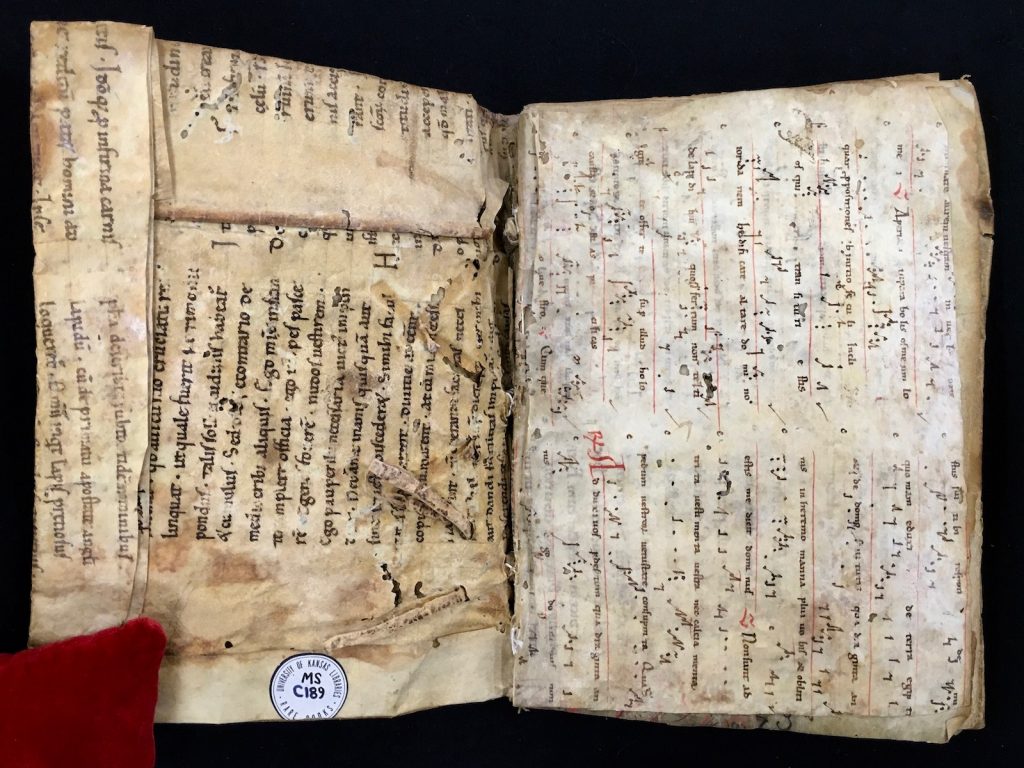

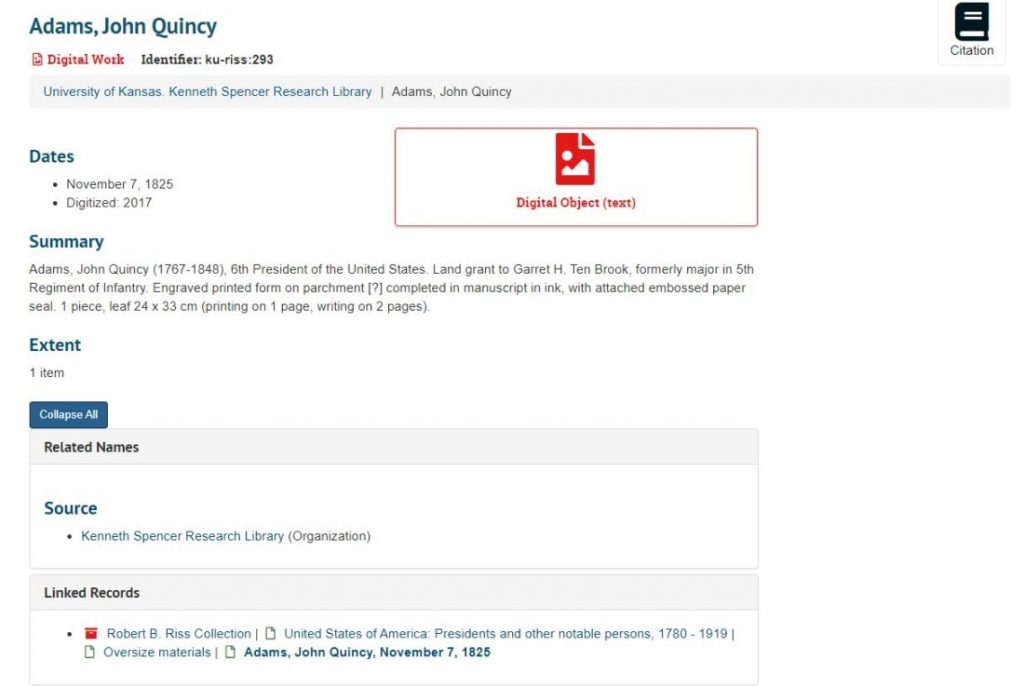

–Letter from Gwendolyn Brooks to Van Allen Bradley, April 21, 1950, Call #: RH MS 152:A:1

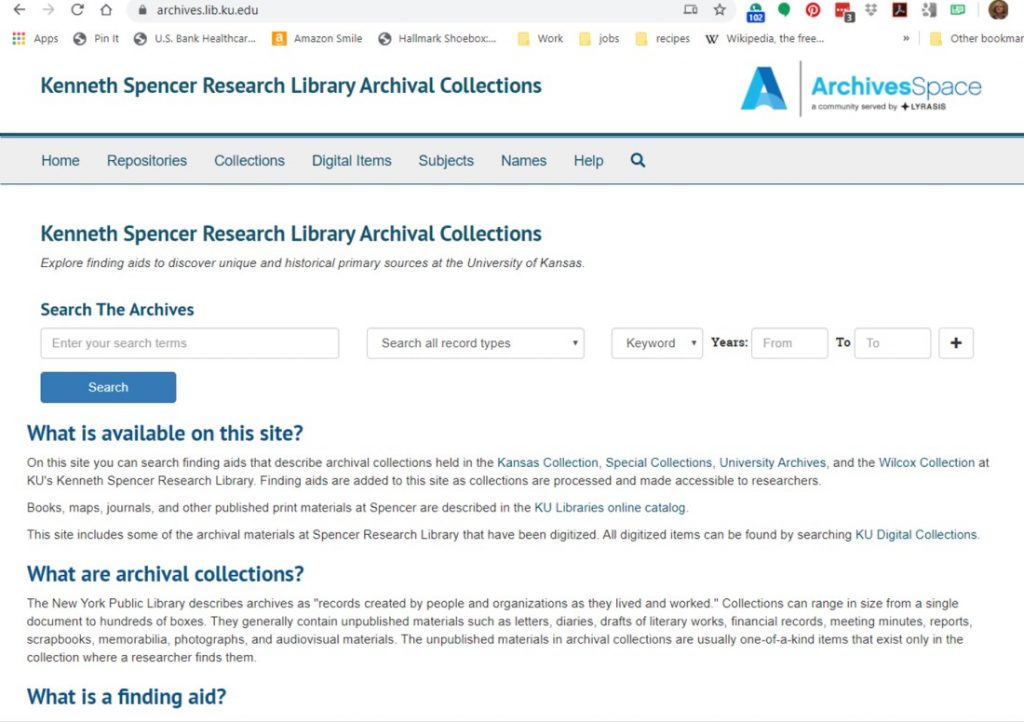

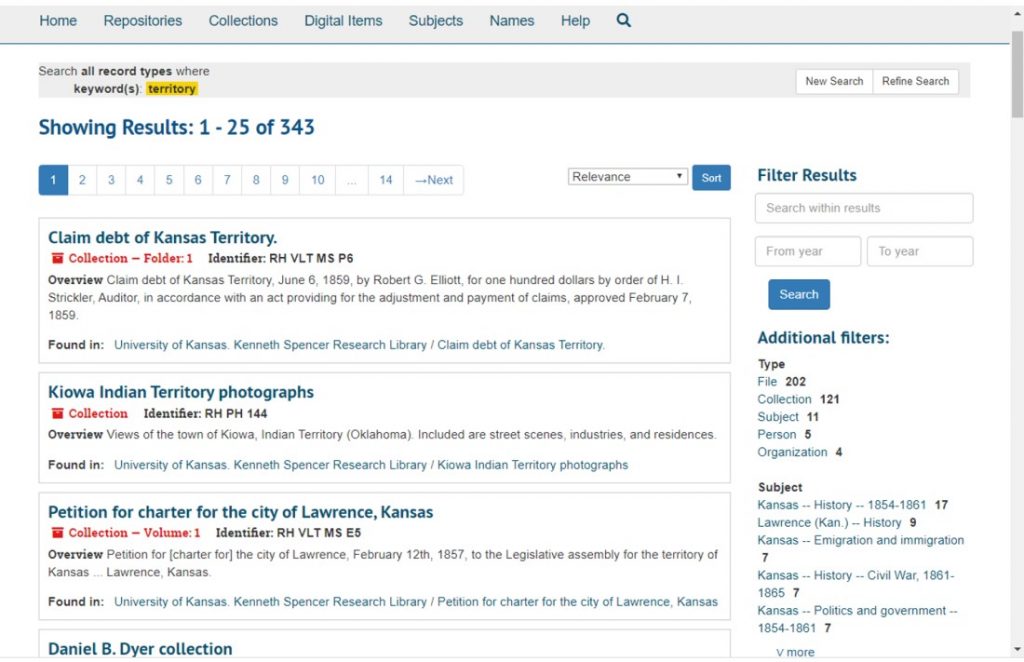

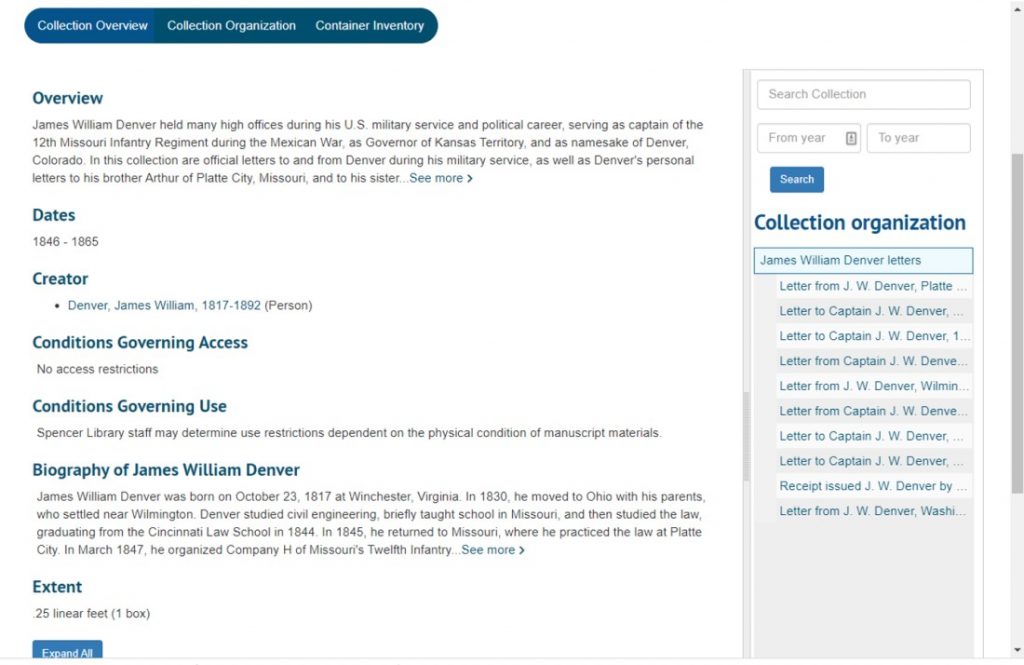

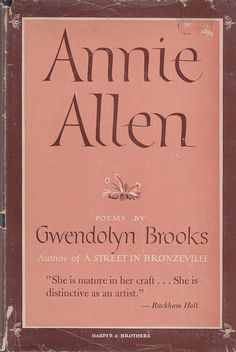

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1950 Pulitzer Prize win for her volume of poetry Annie Allen (1949). Illinois justly claims Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) as one of the state’s most-celebrated literary citizens. Her first collection of verse, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), offered portraits of life in Chicago’s South Side, where Brooks grew up and lived, and she would return to that setting across many of her works. She also served as Illinois’s poet laureate from 1968 until her death in 2000. However, Kansans are quick to remember that Brooks also had ties to the sunflower state. She was born in Topeka in 1917, before she moved a month later with her Kansan parents two states to the east. Spencer Research Library’s Kansas Collection holds first editions of many of Brooks’s books, particularly her early ones, and although her papers reside at the University of California Berkeley and the University of Illinois, Spencer houses a small but significant collection of the poet’s correspondence with Van Allen Bradley (1913-1984). Bradley served as literary editor of the Chicago Daily News, and Brooks occasionally wrote book reviews for the newspaper. Though her relationship with it wasn’t as longstanding or deep as with the Chicago Defender, the influential African American newspaper that combated segregation and racial injustice, several of the letters with Bradley in Spencer’s collection offer insight into her 1950 Pulitzer win.

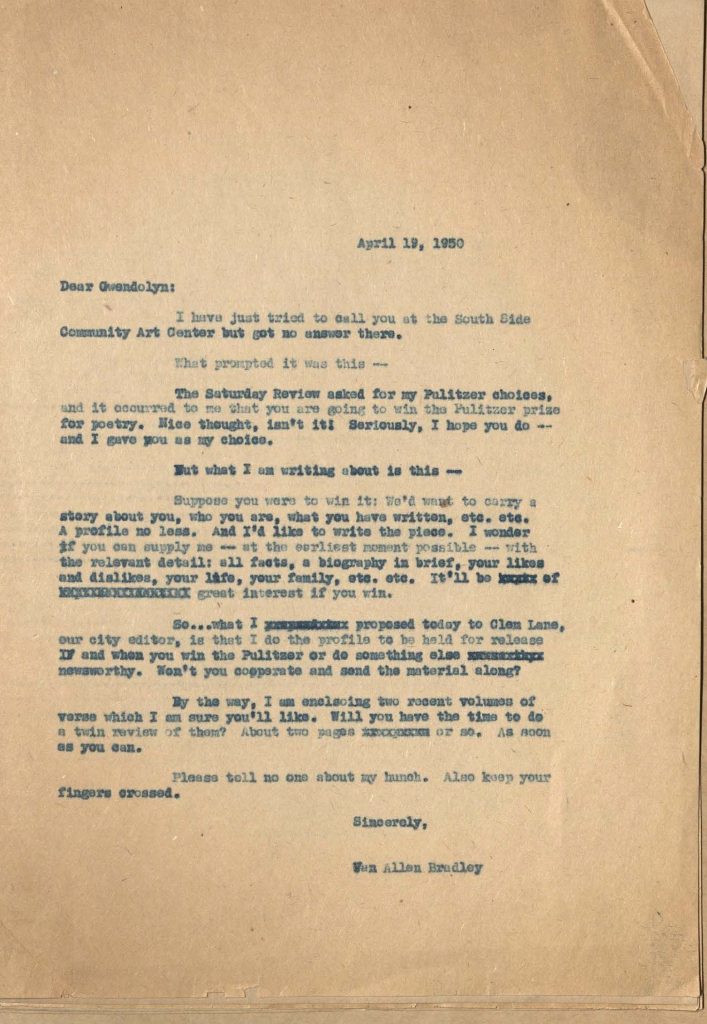

On April 19, 1950, Van Allen Bradley wrote to Brooks,

I have just tried to call you at the South Side Community Art Center [where Brooks worked as a part-time director’s assistant] but got no answer there.

What prompted it was this –

The Saturday Review asked for my Pulitzer choices, and it occurred to me that you are going to win the Pulitzer prize for poetry. Nice thought, isn’t it! Seriously, I hope you do – and I have you as my choice.

But what I am writing about is this –

Suppose you were to win it: We’d want to carry a story about you, who you are, what you have written, etc. etc. A profile no less. And I’d like to write the piece. I wonder if you can supply me – at the earliest moment possible – with the relevant detail: all facts, a biography in brief, your likes and dislikes, your life, your family, etc. etc. […]

_

Bradley’s Pulitzer speculation was not the first awards attention directed at poems from Brooks’s second collection. In November of 1949, Brooks had closed a letter to Bradley with good news. “Guess what:” she wrote, “I won a prize from Poetry Magazine this month – The Eunice Tietjens Memorial Prize of one hundred dollars!” The award honored “a poem or a group of poems by an American citizen published in Poetry,” and Brooks had won it for “Four poems” published in the magazine’s March issue (three sonnets from the sequence “The Children of the Poor” and the poem “A Light and Diplomatic Bird,” all also included in Annie Allen).

Even with that win under her belt, Brooks’s response to Bradley’s Pulitzer speculation was modest. In the remark quoted at the beginning of this post, she ventured that the prize would go instead to Robert Frost. “I’ll never forget that with all of the other poets to choose from, you voted for me,” she wrote to Bradley, “Thank you; thank you!”

While 1949 had been a banner year for Frost—it saw the publication of his Complete Poems and his 75th birthday—the 1950 Pulitzer Advisory Committee was interested in celebrating fresh work rather than past glory. It marveled at the achievement of Frost’s career-spanning collection, but noted he had been awarded the Pulitzer four times previously for essentially the same poems. “A further ‘honor’ to Frost would be not only superfluous but so repetitious as to seem silly,” commented poet and committee member Louis Untermeyer.[i] In Annie Allen, however, the committee saw “a volume of great originality, real distinction and high value as a book, as well as poetry.”[ii] Committee member Alfred Kreymborg commended Brooks’s volume as introducing “further characters out of her South Side background, with Annie herself as the central figure with her peregrinations from childhood through girlhood to womanhood.” He singled out for particular praise The Anniad, “whose title” he wrote, “deftly parodies The Aeneid and whose intellectual sweep over common experience is not only brilliant but profound in its tragic and tragicomic implications.”[iii]

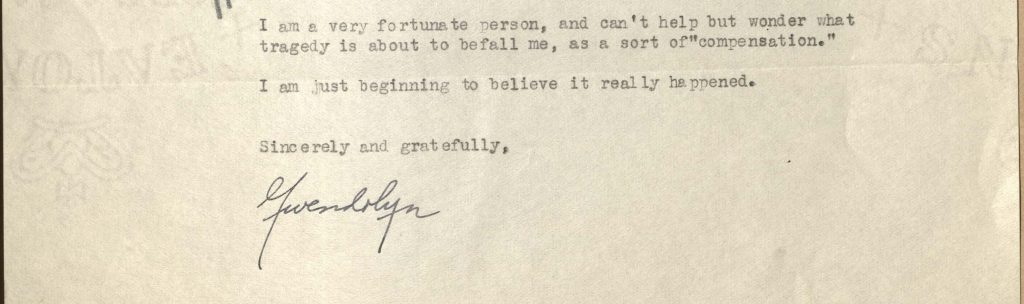

In spite of her assertion that it would be Frost’s year, Brooks nevertheless sent along a biography to Van Allen Bradley with her letter of April 21st. Ten days later, on May 1, 1950, she made history. Annie Allen took that year’s prize for poetry and Gwendolyn Brooks became the first African American writer to win a Pulitzer. “I am a very fortunate person, and can’t help but wonder what tragedy is about to befall me, as a sort of ‘compensation,'” she wrote to Bradley on May 6th.

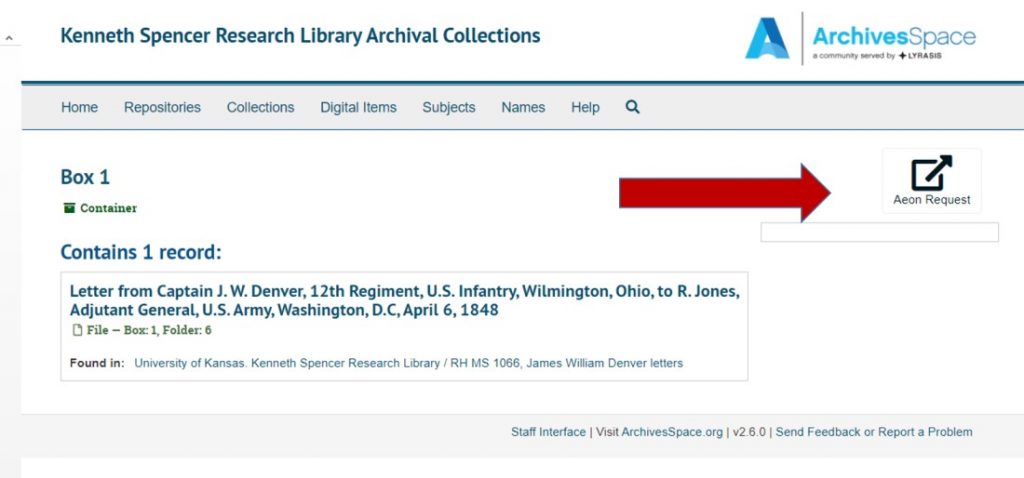

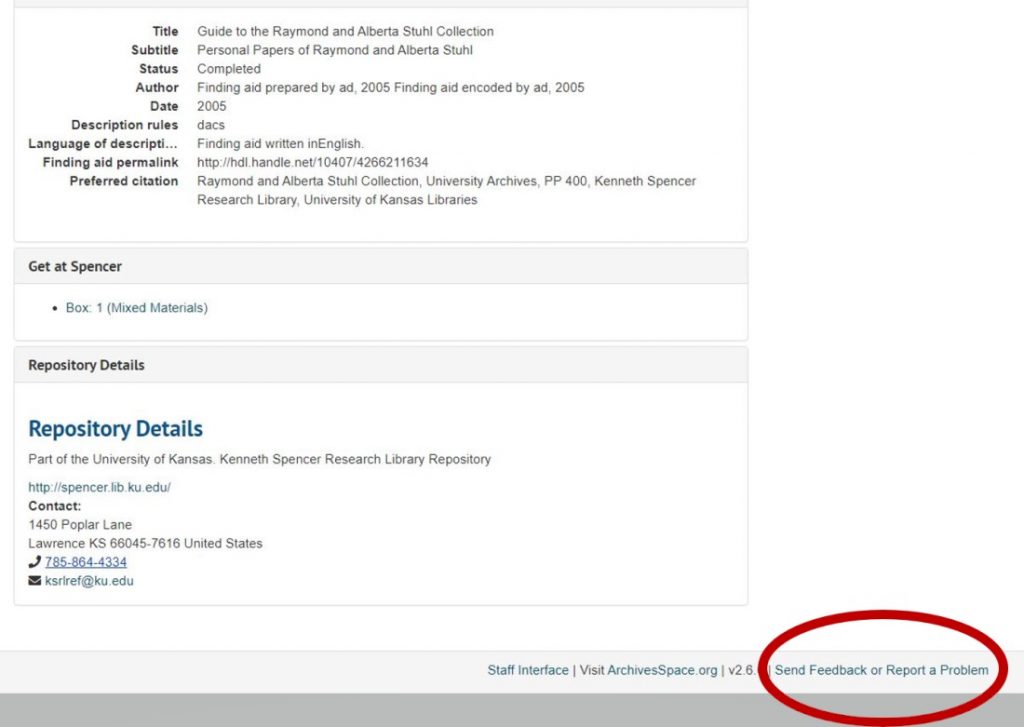

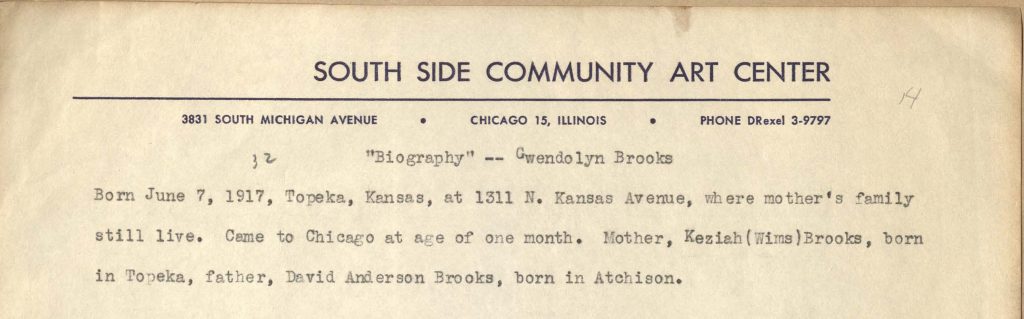

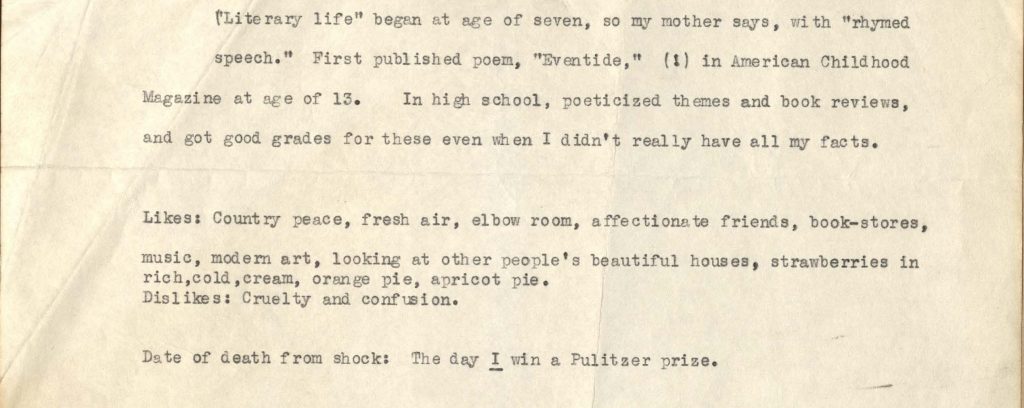

The brief two-page (auto)biography that Brooks sent to Bradley on the eve of her win is worth reading in its entirety. We encourage you to come in and examine it (alongside other Brooks materials) once the danger of coronavirus subsides and our reading room re-opens or to submit a remote reference request. Typed on South Side Community Art Center letterhead, Brooks begins her biography with a recognition of her familial ties to Kansas.

After providing further biographical details and information on her family, schooling, career, past honors, and projected future publications, the thirty-three-year-old Brooks, with a mix of good humor and commitment, offers up a brief account of her literary start. She also provides, in response to Bradley’s request, her likes (“Country peace, fresh air, elbow room, affectionate friends, book-stores, music, modern art, looking at other people’s beautiful houses, strawberries in rich, cold cream, orange pie, apricot pie”) and dislikes (“cruelty and confusion”). She then concludes her biography with one final self-effacing but playful detail: “Date of death from shock: The day I win a Pulitzer prize.”

As we mark National Poetry Month during a time of social distancing, we encourage you to explore Brooks and her Pulitzer-winning volume Annie Allen through some of the numerous resources available online:

- Several poems by Gwendolyn Brooks, including “The Rites for Cousin Vit” from Annie Allen, are available online at Poetry Foundation. There you’ll also find back issues of Poetry Magazine, including the March 1949 issue containing the four poems from Annie Allen that earned Brooks the Eunice Tietjens Memorial Prize.

- Listen to Gwendolyn Brooks read her own poetry in a recording made on January 19, 1961 for the Library of Congress’ Archive of Recorded Poetry And Literature at https://www.loc.gov/item/94838388/. Brooks’s reading includes poems from Annie Allen starting at the 11:55 minute mark, including “The Rites for Cousin Vit” (at 19:24), as well as several of her other best-known poems, such as “Kitchenette Building” (at 0:34) from A Street in Bronzeville (1945) and “We Real Cool” (at 22:50) from The Bean Eaters (1960).

- Finally, commemorate Brooks’s Pulitzer Prize win and her Kansas roots with this trading card produced in 2016 by the Kansas State Historical Society.

Elspeth Healey

Special Collections Librarian

[i] Remarks by Louis Untermeyer, quoted in a letter from Henry Seidel Canby to Dean Carl W. Ackerman, Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University, on behalf of the Pulitzer committee—Henry Seidel Canby, Alfred Kreymborg, and Louis Untermeyer, [1950]. Reproduced in “Frost? Williams? No, Gwendolyn Brooks.” The Pulitzer Prizes. Accessed 6 April 2020. https://www.pulitzer.org/article/frost-williams-no-gwendolyn-brooks

[ii] Letter from Henry Seidel Canby to Dean Carl W. Ackerman, Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University, on behalf of the Pulitzer committee—Henry Seidel Canby, Alfred Kreymborg, and Louis Untermeyer, [1950]. Reproduced in “Frost? Williams? No, Gwendolyn Brooks.” The Pulitzer Prizes. Accessed 6 April 2020. https://www.pulitzer.org/article/frost-williams-no-gwendolyn-brooks

[iii] Remarks by Alfred Kreymborg quoted in ibid.