In the Moment of “Something Else,” Native American Heritage Honors “Something Meaningful” in Indigenous Studies at the University of Kansas

November 18th, 2020This week’s blog post has been guest written by L.Marie Avila, an Undergraduate Engagement Librarian at KU Libraries, and Carrie Cornelius, the Acting Supervisory Librarian at Tommaney Library at Haskell Indian Nations University.

In 1991, Congress proclaimed the month of November as a time to acknowledge Native American Heritage (PL 101 343). In honor of Native American Heritage, we would like to draw attention and reverence to the Indigenous Nations Studies Program collection (Call Number: RG 17/71) found in the University Archives at Spencer Research Library.

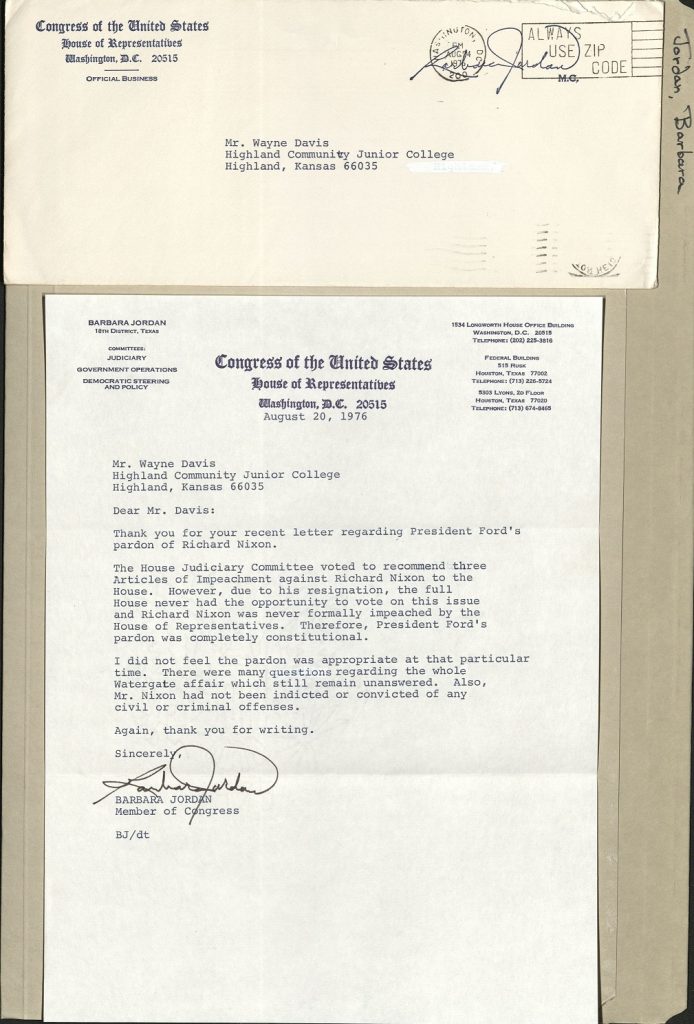

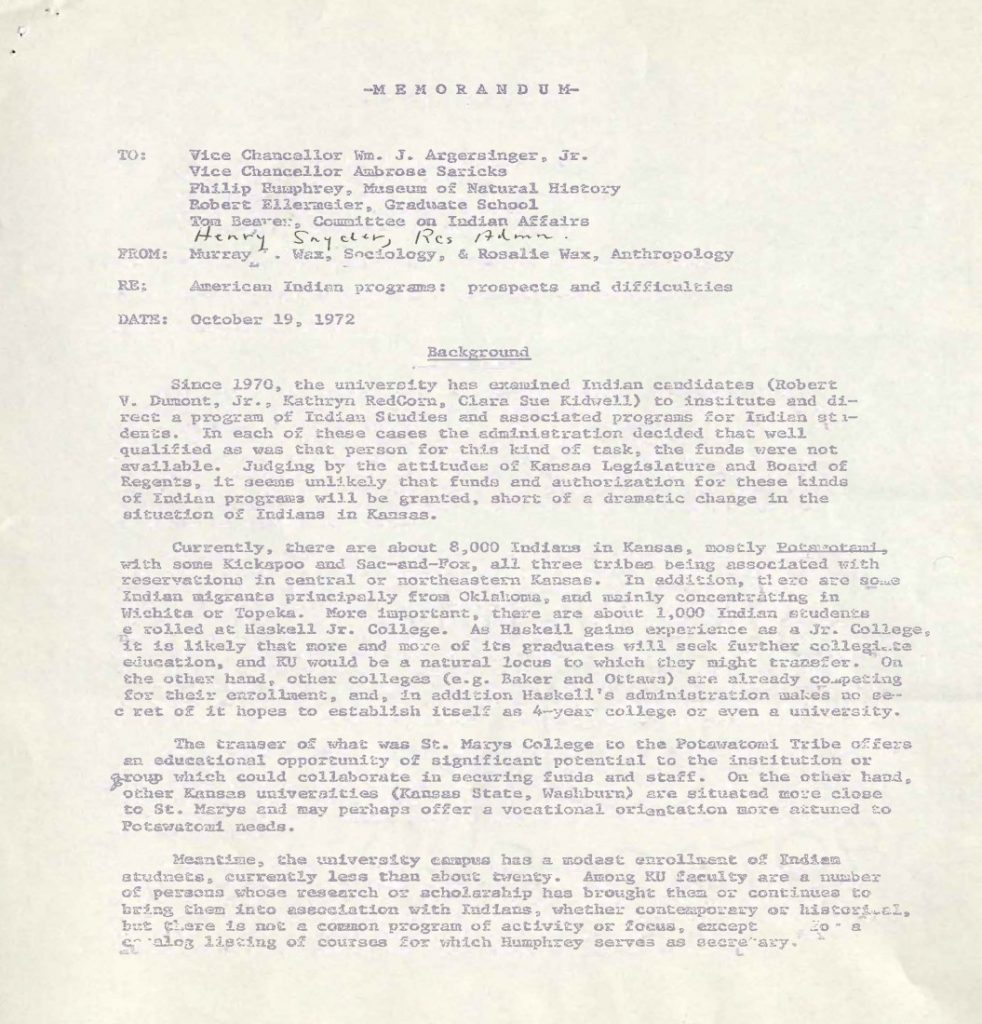

Kenneth Spencer Research Library holds the documents of the Indigenous Nations Studies Program, which signify the decades of effort by University of Kansas scholars to improve the opportunities for Indigenous students. This collection consists of a variety of communications: memos among academics and sovereign tribal nations; program development proposals; articles; and university news releases.

There, with the assistance and expertise of the staff, is a pathway to the access and discovery in research. Our research led to significant artifacts in the early discourse and vision in establishing the program dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, and records of the events and the scholarly accomplishments of native students and scholars in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Included in the artifacts is the historical partnership between the University of Kansas and Haskell Indian Nations University.

This is in dedication to Native peoples’ resiliency, and to impress to the next generations of learners, to acknowledge the historical and contemporary contributions of Native people, throughout all seasons.

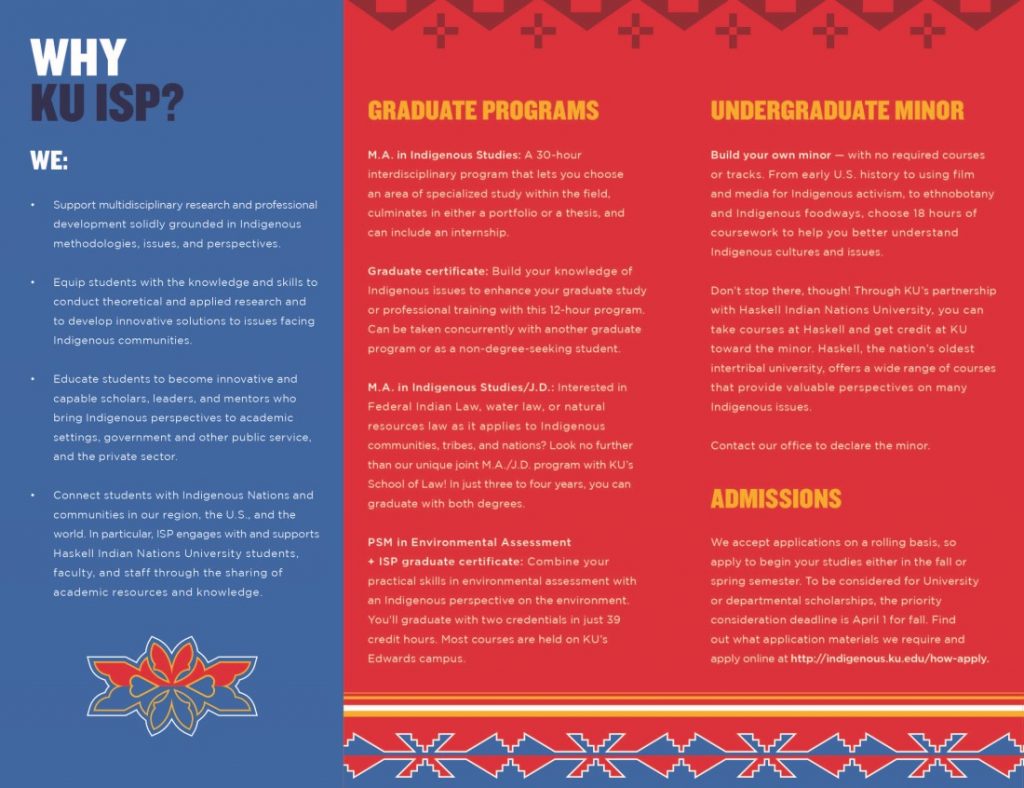

To begin, we examine the current 2020 Indigenous Studies Program Brochure for Indigenous Methodology noting the flexibility, student choice, and opportunity to direct research to community improvement. All of which was the direct result of the communication and program review noted in the historical documents, each showing the passion and dedication of scholars pursuing excellence for KU’s Indigenous students.

The 2020 Indigenous Studies Program illustrates the inclusion of Indigenous Methodologies, while partnering not only with Haskell Indian Nations University, but Indigenous communities of the world. Students focus their Indigenous studies and research not only in Indigenous content, but with purpose to problem-solve the unique needs of Indigenous communities. Skill-based programs and build-your-own courses allow for individualized design and show flexibility and individualized student choice.

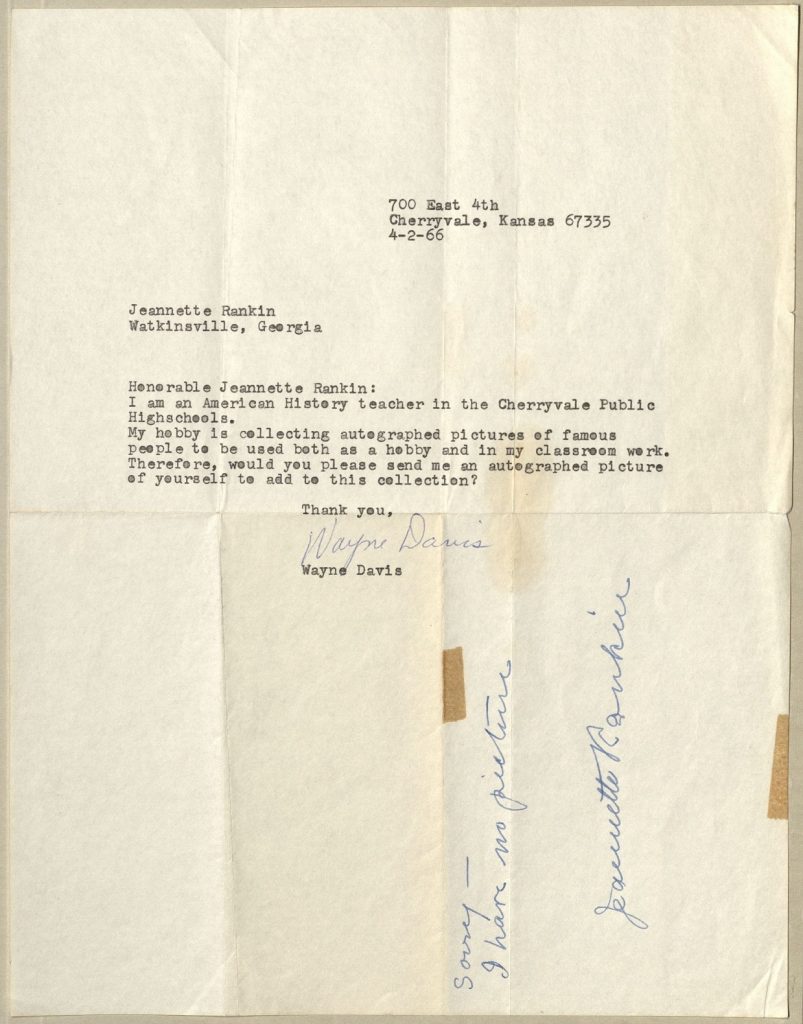

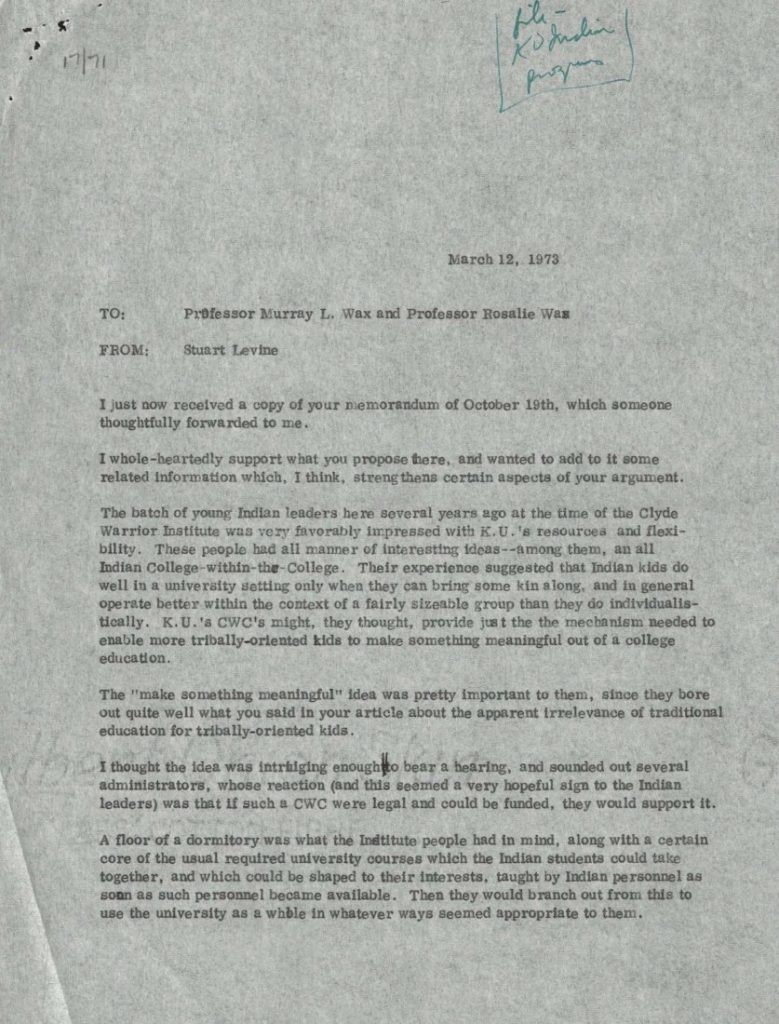

A step back gives the opportunity to gain insight to the process. This early artifact (below) looks at the promise and challenge in developing a program dedicated to Indian studies.

Illustrated in a meaningfully-written letter by a KU professor, the letter below captures the Indigeneity of Indian students and their ultimate regard to “make something meaningful” out of a college education and an Indian Center in the space. The document provides insight into the 1973 “Indian work” strategies that were systematically and proportionally selecting tribal students by their traditionality. Additional strategies included housing together, scheduling core courses together, and mentoring by tribal teachers.

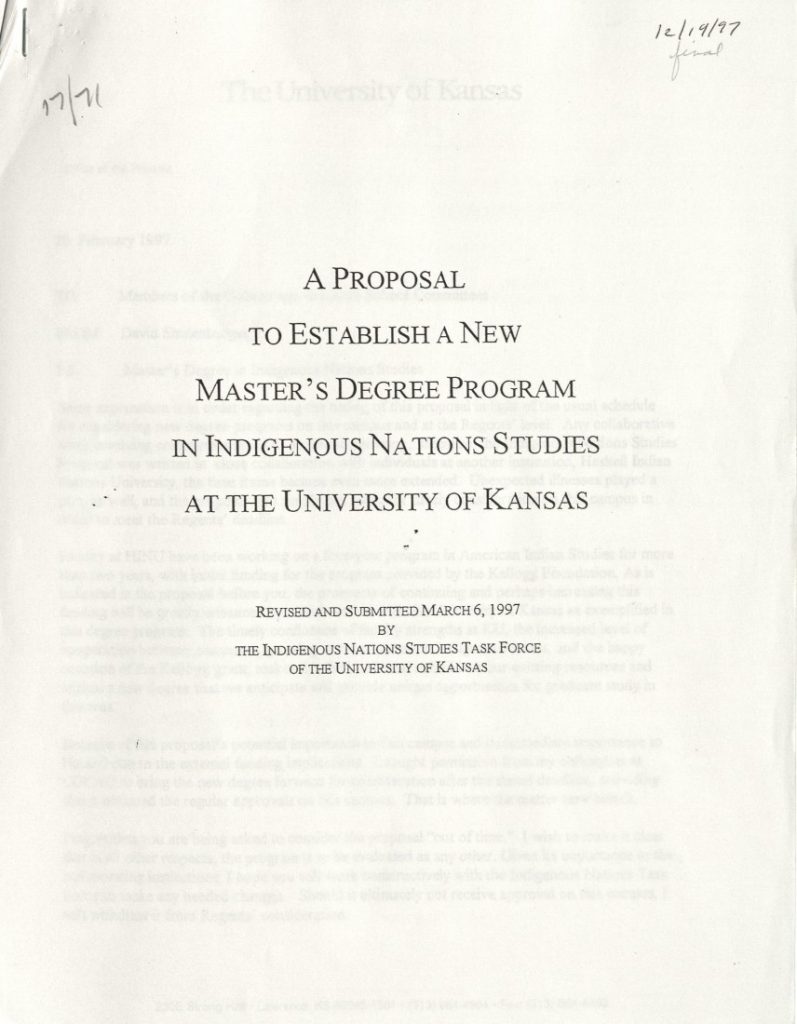

Moving into the end of the twentieth century is an in-depth proposal from KU’s Indigenous Nations Studies Task Force.

To conduct in-depth research in this subject area, and others, make an appointment to visit Kenneth Spencer Research Library.

For more information about the term “something else,” see the Indian Country Today article “‘Something else’ may make all the difference this election.”

L.Marie Avila, Urban Waganakasing Odawa

Undergraduate Engagement Librarian

University of Kansas

Carrie Cornelius, Prairie Band Potawatomi, Oneida

Acting Supervisory Librarian

Tommaney Library, Haskell Indian Nations University