From the Stacks to the Internet: Making Spencer’s Japanese Collections Accessible Through Digitization

March 20th, 2024Projects in Spencer are rarely the work of a single individual; instead, they often involve drawing in individuals across all corners and departments of the library. And when you’re very lucky, you can even call in the cavalry and recruit outside help. This has been the case in one of our ongoing projects centering around digitizing – or creating online digital reproductions – of a subset of our Japanese materials.

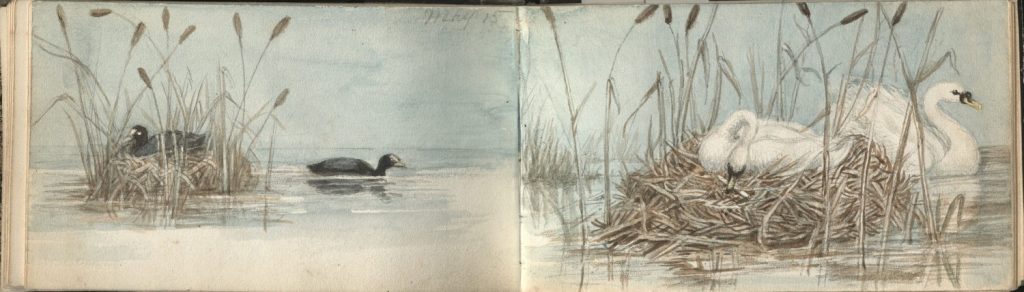

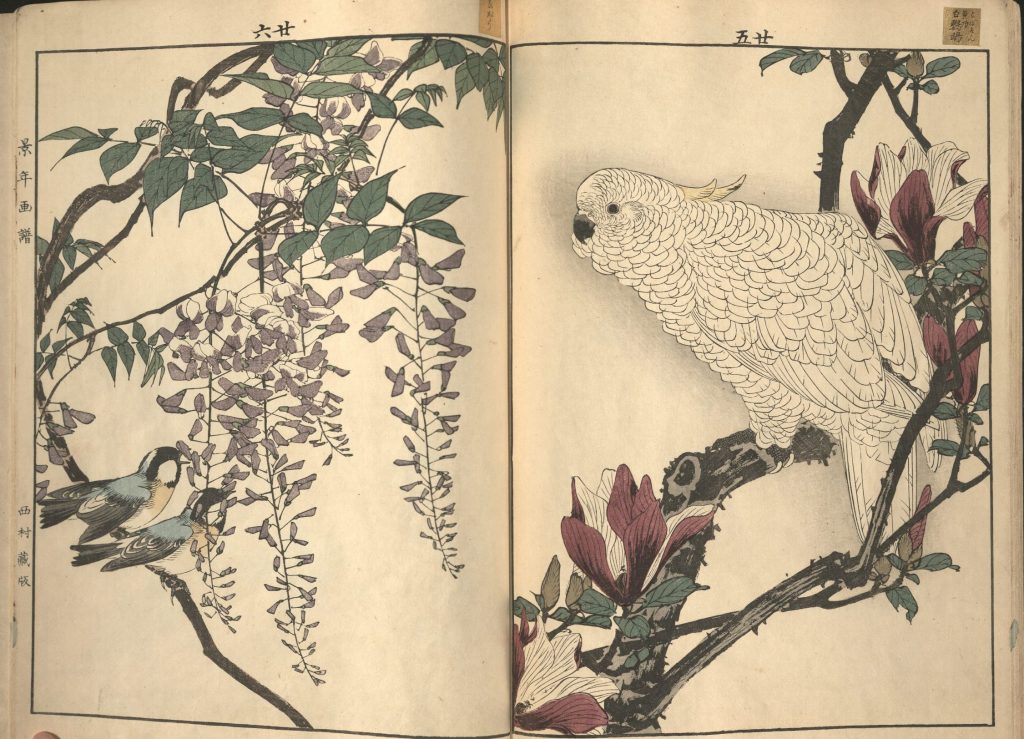

Spencer is home to an exceptional collection of materials dedicated to Natural History and particularly to ornithology and the study of birds. Thanks to several substantial acquisitions in the 1960s, we now have an exciting and unique range of Japanese works of falconry and artwork of birds spanning from the early 16th through the early 20th centuries that stand as a bright jewel within our ornithological crown. Our ongoing digitization project aims to help bring these materials to a wider audience and to connect our collection to researchers across the globe.

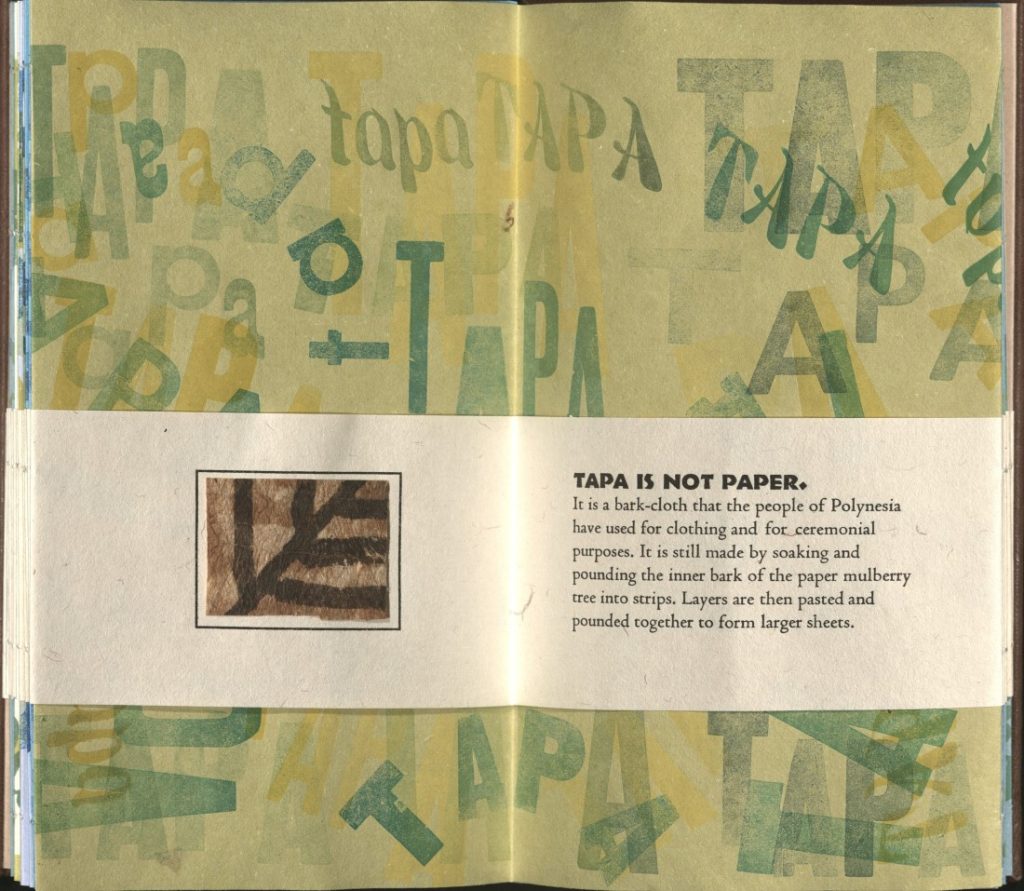

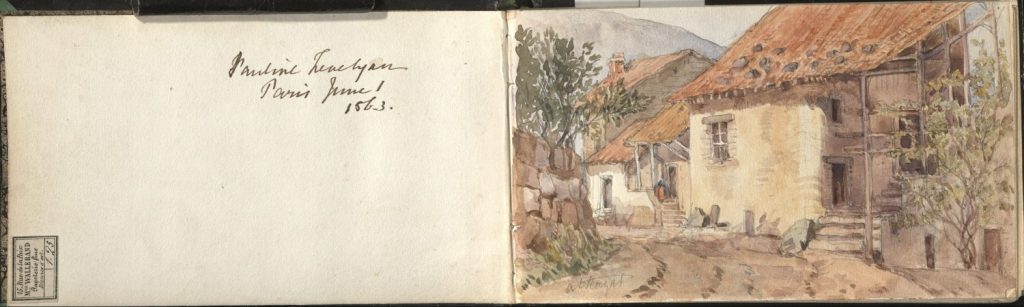

Woodblock prints No. 5 and 6 from Keinen kachō gafu by Imao Keinen, 1891-1892.

Call Number: Ellis Aves G21

To achieve this goal, we have been hard at work both within the KU libraries: the project was conceived by KU Japanese Studies Librarian Michiko Ito, and throughout the project, she has dedicated substantial time towards helping us enhance the depth and detail of many of our catalog records for these items – in doing so, she ensures that researchers who search our catalogs will be able to find the materials more easily, and will know more about the items in terms of their content, their artists and authors, when and where the book was made, and more. Michiko’s language and subject expertise have been bolstered by the cataloging skills of our Head of Cataloging and Archival Processing, Miloche Kottman, who has helped Michiko with the unique challenges that rare books and materials can present in cataloging them.

Part of this process has also involved tracking down the provenance of these materials – the history of how they came to have a home on Spencer’s bookshelves. M own work as one of Spencer’s Special Collections curators has come into play in tracking down old purchase records in our files, to help us trace the physical migration of books across space and time, so that we can add this information to our catalog records and metadata.

And Michiko reached out across oceans, contacting the National Institute of Japanese Literature about the possibility of linking our digitized materials with their international database of digitized Japanese literature so that when scholars search the database, they can find and view Japanese rare books from libraries across the globe. As part of this collaboration, one of their affiliated scholars, Dr. Kazuaki Yamamoto, flew here from Japan to further decipher the many exciting details of our collections. He helped identify ownership marks to trace the history of these items over the centuries, dated materials, and identified arcane and obsolete vocabulary and handwriting.

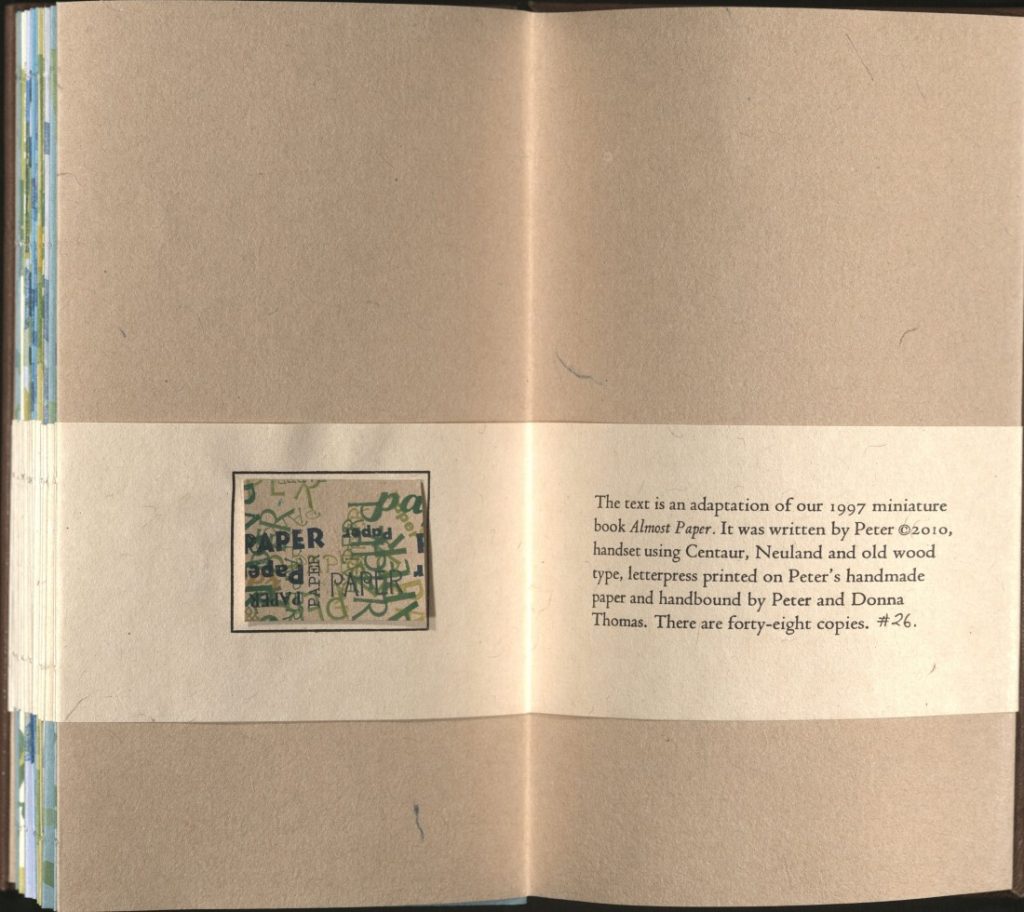

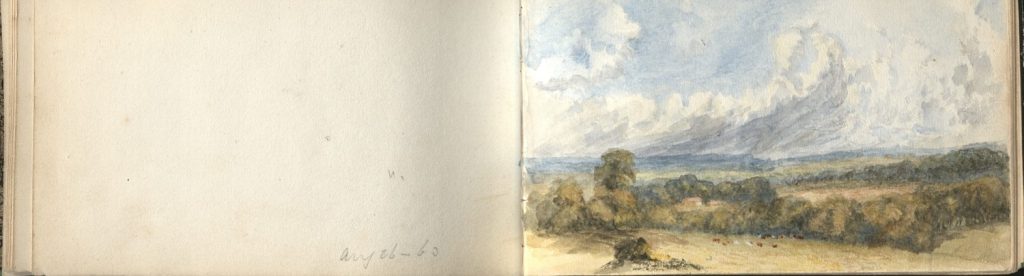

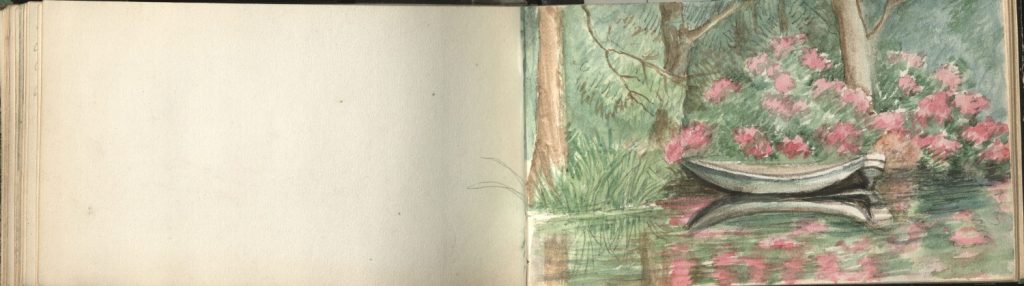

Woodblock prints from vol. 1 of Bunrei Gafu by Maekawa Bunrei, 1885. Call Number: Ellis Aves E241

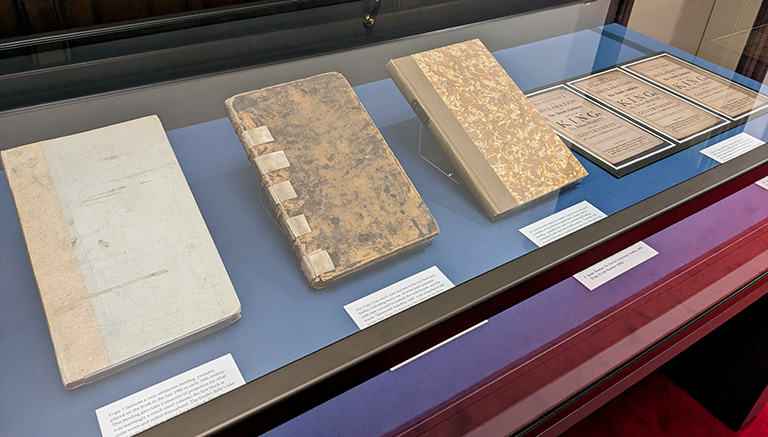

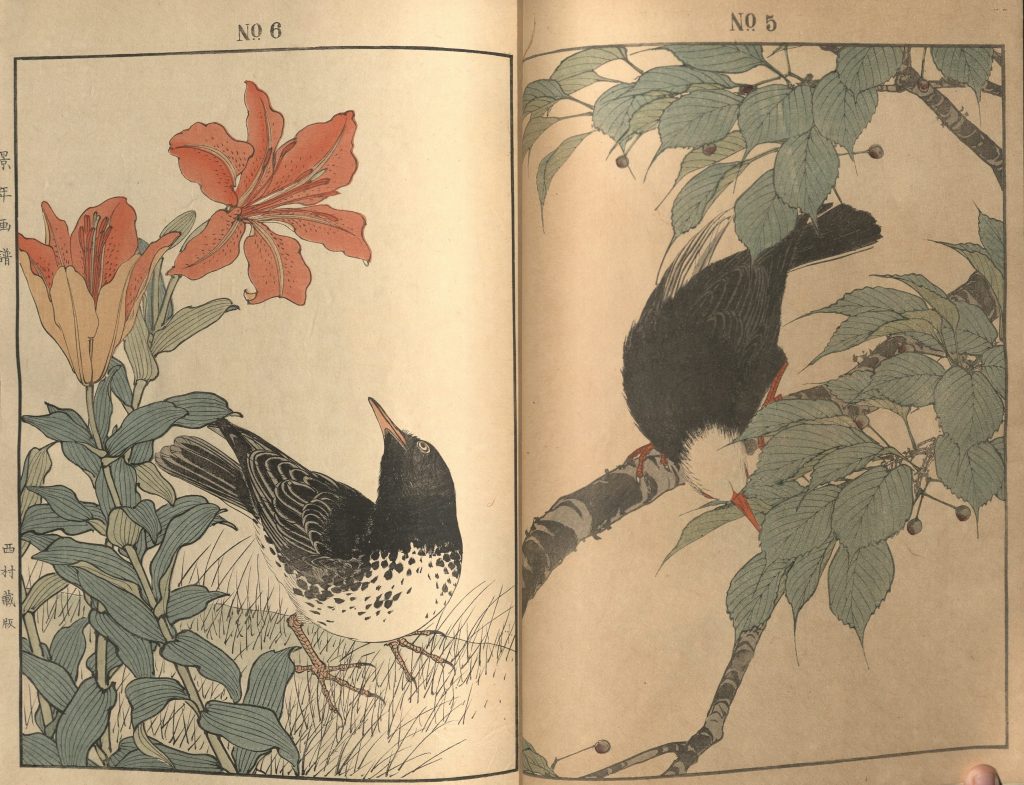

Meanwhile, our Conservation team’s representative, Angela Andres, has been involved in reviewing the items to ensure that they are in safe and stable conditions and ready for digitization. Japanese paper, called washi, is renowned for its soft texture, but its softness can leave it fragile, and their book covers are sometimes coated in powdered mica to give a metallic sparkle, but it leaves the covers vulnerable to friction and wearing away over the centuries. Her work has involved crafting new protective enclosures for some of the more delicate materials, which will help support the softer paper when it’s shelved upright and minimize any friction and rubbing that might wear away the mica coating. Doing so helps us protect and preserve the originals so that they survive together with their online copies.

Selected page from Shasei. Kincho bu, by Yoshiki Gyokei, 1853, with a custom box and interleaved acid-free paper to protect the delicate pages. Call Number: MS G49

The next step, hopefully coming soon, is to send the items down to our digitization team helmed by Melissa Mayhew, where they will be scanned into high-resolution TIFF files and with the help of our Digital initiatives librarian Erin Wolfe, they’ll be uploaded onto the online platforms of both the University of Kansas and the National Institute of Japanese Literature’s database with relevant metadata to help researchers connect our collections with books and manuscripts from other libraries around the world.

In many ways, this project embodies all the work and challenges that can go into Special Collections libraries and the efforts we make toward making delicate and rare materials accessible to as many people as possible. From cataloging to preserving, to digitizing and uploading them to the greater internet, no librarian works alone!

Eve Wolynes

Special Collections Curator

![Sepia-toned photo of a dirt street with two-story buildings - and some horses and wagons - on each side. A handwritten note says "2803 Chesnut [sic] St, Hays, Kans."](https://blogs.lib.ku.edu/spencer/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/RH-PH-134_Hays-front-1024x650.jpg)