Charlton Hinman, Optical Collation, and the Big Grey Machine

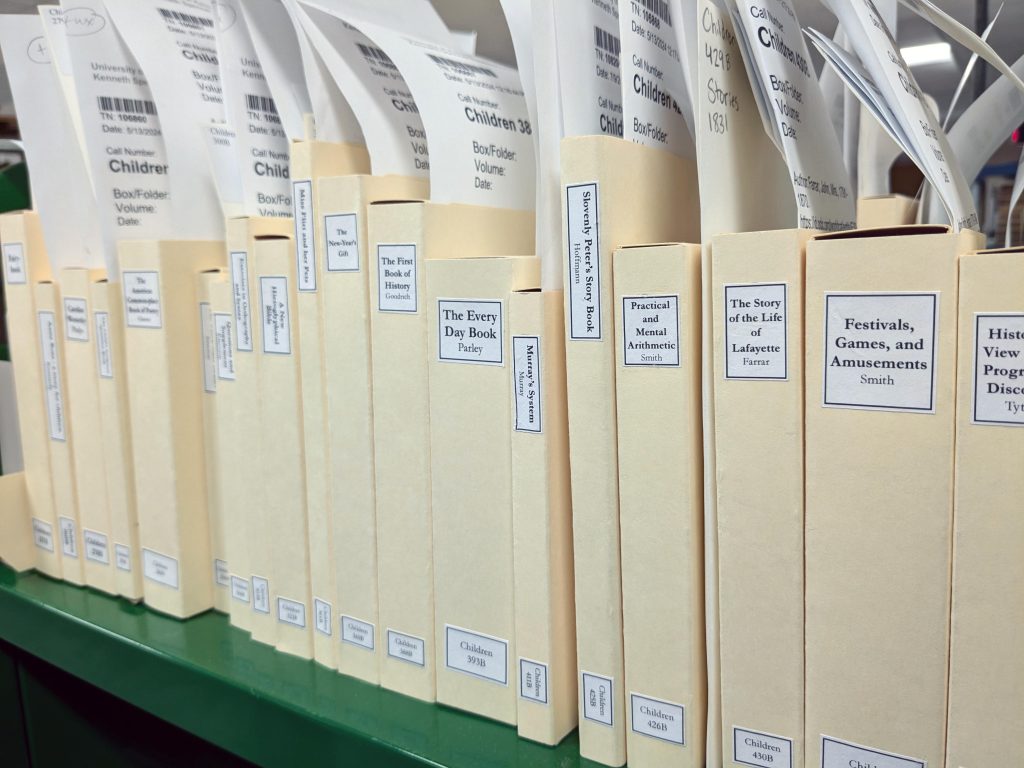

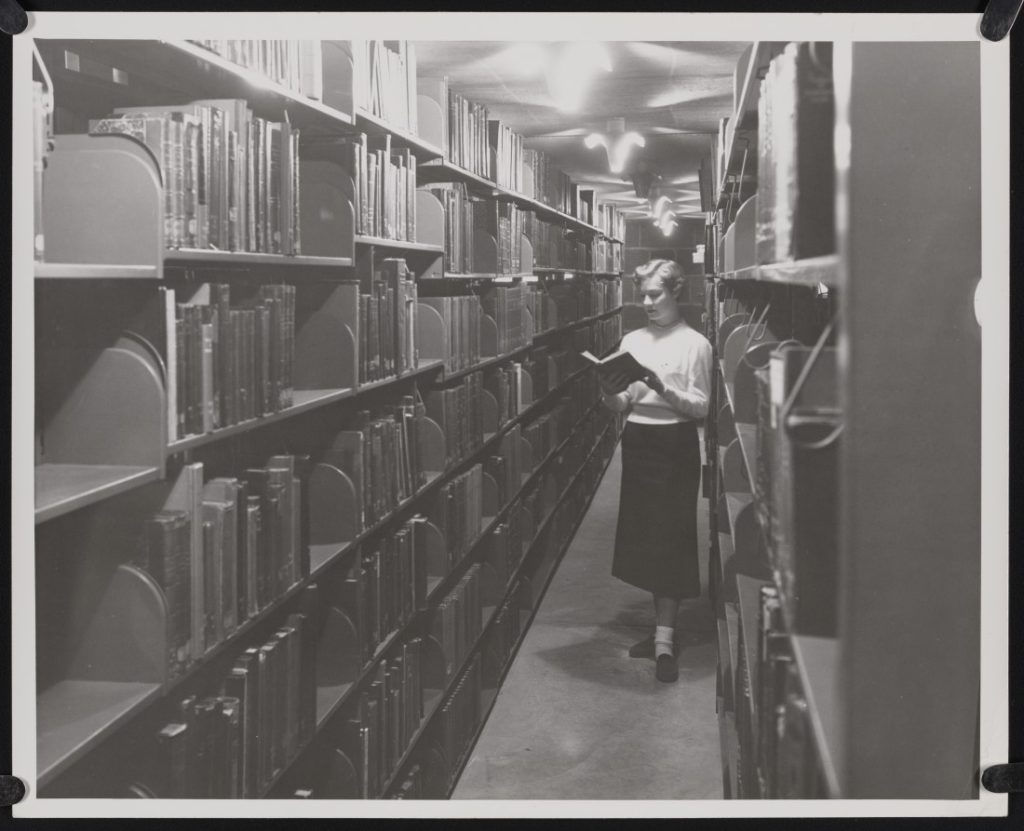

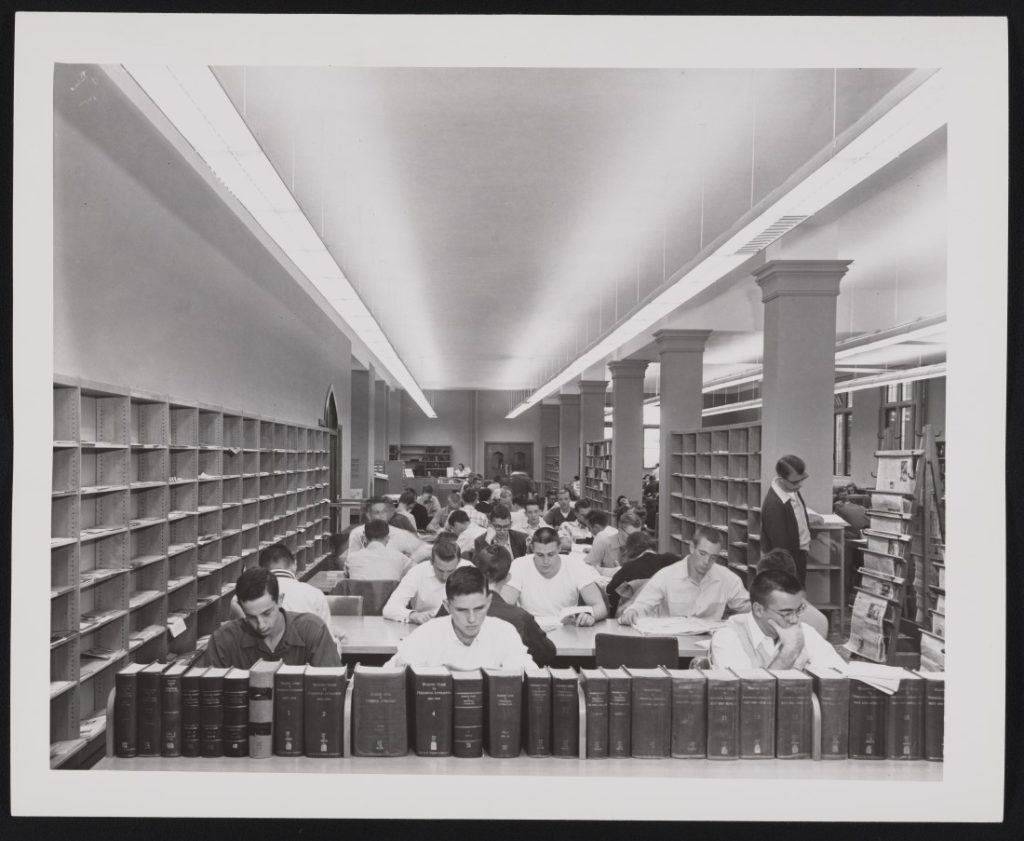

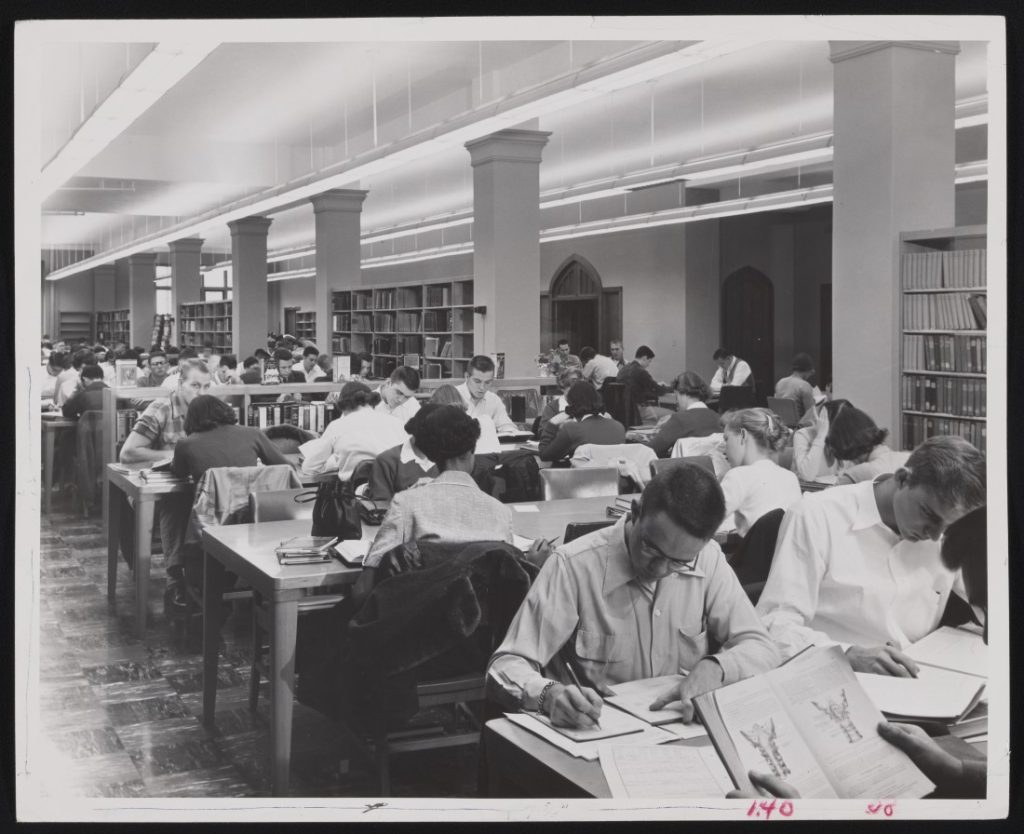

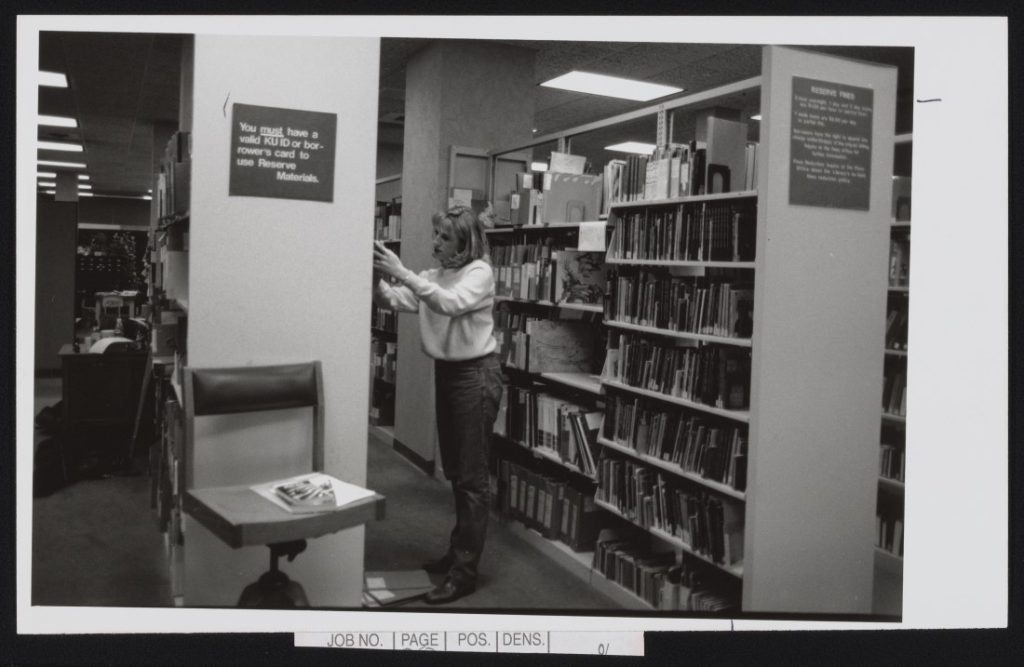

January 12th, 2026Charlton Hinman was a looker. Of course, that was true of so many of Fredson Bowers’ students – they tended to be lookers. We won’t make any comment on the relative attractiveness of Charlton Joseph Kadio Hinman or Bowers’ students, but we refer instead to the tradition of close examination and description of books that Bowers codified and Hinman continued here at the University of Kansas. On the north side of the Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room at Kenneth Spencer Research Library is the Hinman Collator, a hulking grey machine that stands as a reminder of (and a tool for) precisely that kind of work. Our colleague Caitlin Klepper wrote a post about the collator previously, but we thought we might delve more in-depth here.

Modern descriptive bibliography – the close physical examination and description of books – begins with Fredson Bowers’ book Principles of Bibliographical Description (1949). Bowers was a professor of English at the University of Virginia, and Charlton Hinman was Bowers’ first PhD student there. Both Hinman and Bowers had analytical minds with similar bents, which served them well in the Second World War. They were involved in cryptography and code breaking, with Bowers again leading Hinman as his commanding officer. Following their service, Bowers returned to Virginia, publishing the aforementioned Principles.

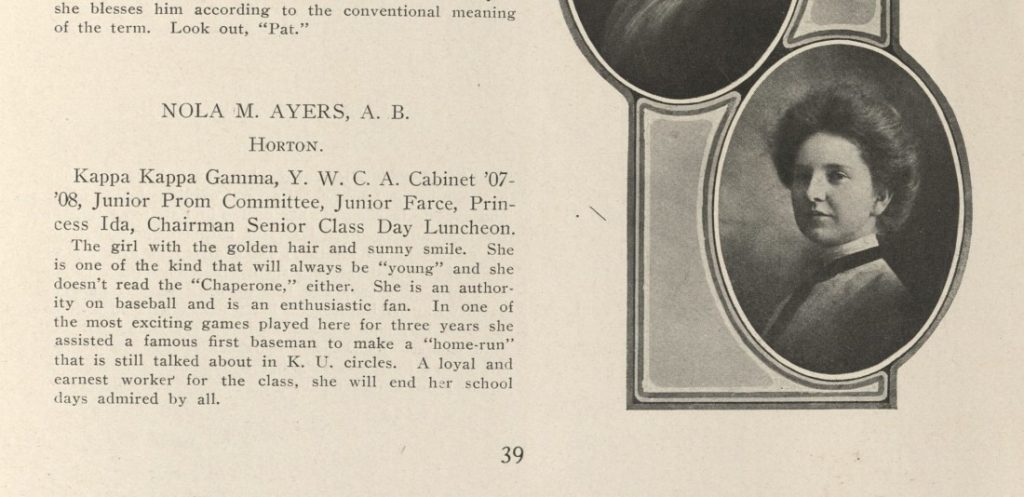

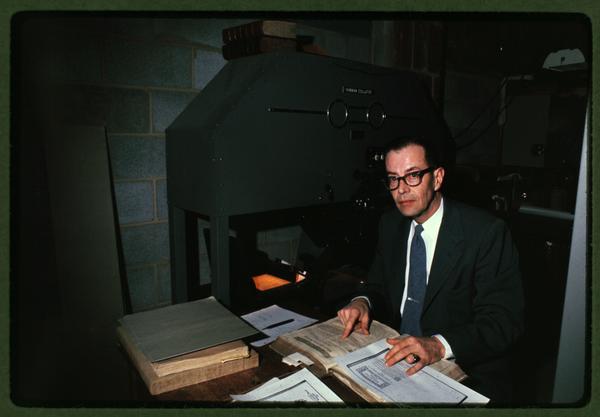

Hinman’s dissertation, The Printing of the First Quarto of Othello, led to his first position as a research fellow at the Folger Shakespeare Library, where he collated copies of the first folio of Othello. It was Hinman’s time as a fellow at the Folger that inspired his creation of the collation machine. Collation – or, the work of examining and describing the physical evidence in a copy of a book – is time consuming. Hinman’s work was even more intensive, as he sought to find all of the different states of the pages down to the most minor corrections or insertions made by the printer in the course of printing the book. Looking at each page of text line by line is an almost impossible task. Hinman hints at this problem in his preliminary essay about the machine, which was titled “Mechanized Collation: A Preliminary Report” and printed in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America in 1947.

Hinman’s time in the military helped point the way to a solution, supposedly through military reconnaissance use of photography. He described the idea of taking two pictures of the same area and rapidly alternating them to spot differences. He didn’t claim he had done it as part of his cryptography work; rather, he claimed he heard about it while in the military. However, the process Hinman described was never used for reconnaissance purposes. While the military did use aerial photography, they didn’t use any method that alternated two images in a similar way to the function of the Collator. In his article “‘The Eternal Verities Verified’: Charlton Hinman and the Roots of Mechanical Collation” (Studies in Bibliography, 2000), Steven Escar Smith writes that “using World War II technology, it simply would not have been possible to photograph the same patch of ground twice from exactly the same altitude and position.” According to Smith, Hinman seems to have acknowledged that the story wasn’t entirely true, but it’s not clear whether he actually discouraged its telling.

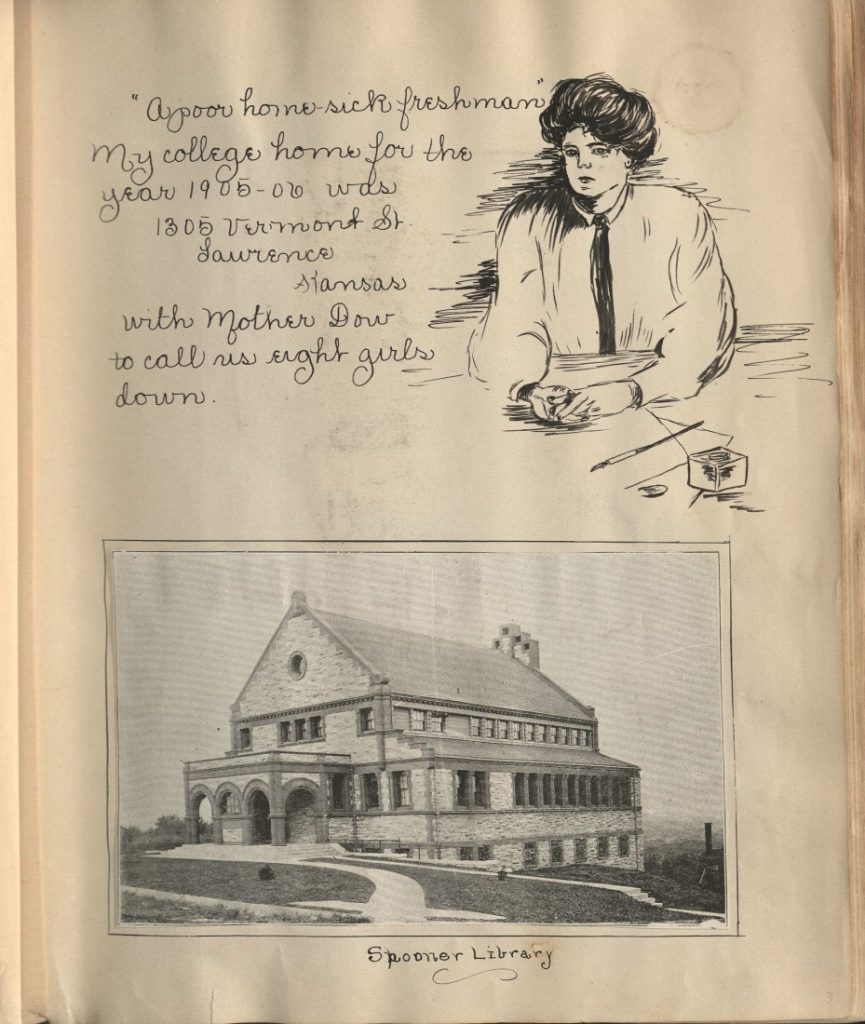

Arthur M. Johnson, Hinman’s partner who took over building and selling collators around 1956, may have been the one to accurately describe how Hinman got the idea for the collator. Johnson wrote that Hinman had studied something that Johnson called an “astronomer’s microscope.” It used the same principle of “blink comparison” to compare images of the night sky, most famously by Kansan (and KU alumnus) Clyde W. Tombaugh in his observation of Pluto. Although it’s not known whether Hinman ever saw or used a blink comparator, he knew of the one at the observatory at UVA when he was a PhD student there. This was the true technological ancestor of Hinman’s machine.

These kinds of devices are simpler than the Hinman Collator in that one can use flat images of similar size – not possible with books. Hinman’s great improvement and contribution, then, was the creation of a machine that could deal with books of different sizes, thicknesses, and even formats. Hinman had a long career as a professor of English, first at Johns Hopkins University (1945-1960) and then at the University of Kansas (1960-1975), where he eventually became a University Distinguished Professor of English. Approximately 50 collators survive. The collator at Spencer (A9 in Steven Escar Smith’s 2002 census of existing Hinman Collators, published in Studies in Bibliography) is one of two that remain that Hinman himself used; the other is at the Folger Library. The effect of the collator is reproduced in this short video by Sam Lemley. Bibliographer J.P. Ascher has also made a good video about how one might use the collator, utilizing the machine at the University of Virginia.

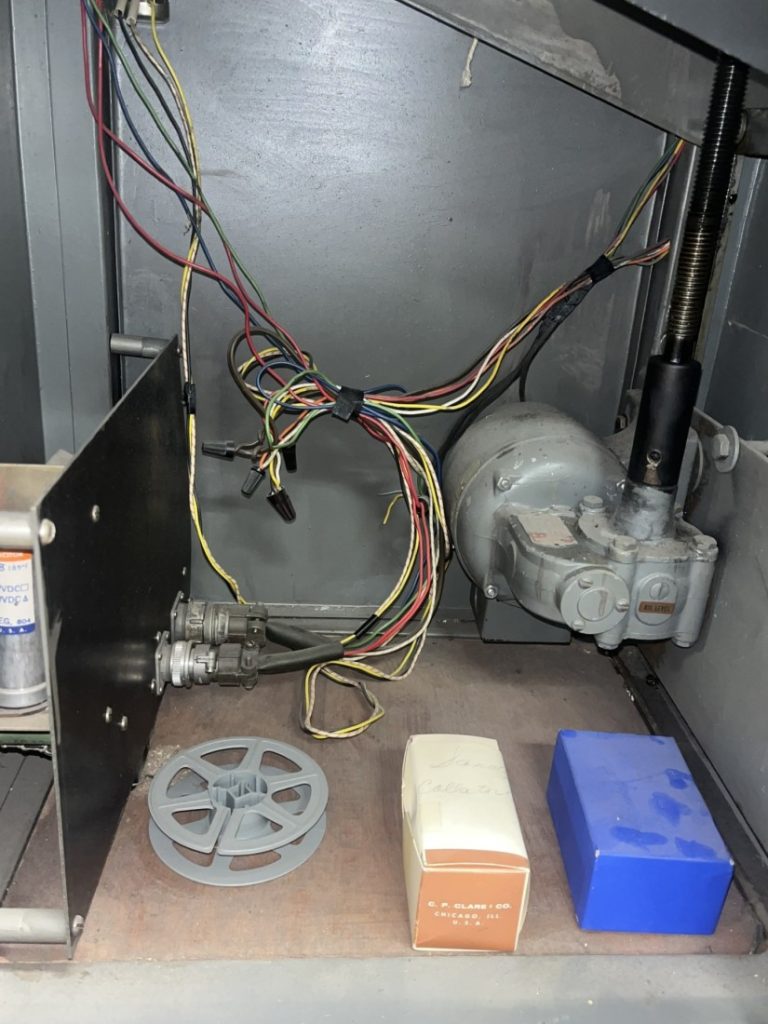

Hoping to actually use Spencer’s machine, we ventured to the Reading Room before opening. We powered it on, and, to our delight, the 400-pound machine came to life. Unfortunately, this was not to be, as we discovered that the “blink” feature, the key function, is not currently working. Thanks to the efforts of our colleague Molly Bauer, we are slowly learning what might be wrong and what the fix might be. Look for a follow-up post in the spring about our efforts, as well as digital alternatives to optical collation that bibliographers can use today.

The Hinman Collator, for now, stands as a testament to the ongoing work of descriptive an analytical bibliography here at the University of Kansas. Much like its creator, the machine is complicated and devoted to a very specific purpose – close looking at material objects we regularly take for granted.

Jason W. Dean and Adrienne Sanders

Rare Materials Cataloging Librarians