Total Eclipse of the Heart(land)

August 18th, 2017In honor of Monday’s total solar eclipse, the Spencer Research Library staff was curious about our collection holdings related to this celestial phenomenon. We found two reports detailing previous solar eclipses, one from South America in 1889 and one from the United States in 1900.

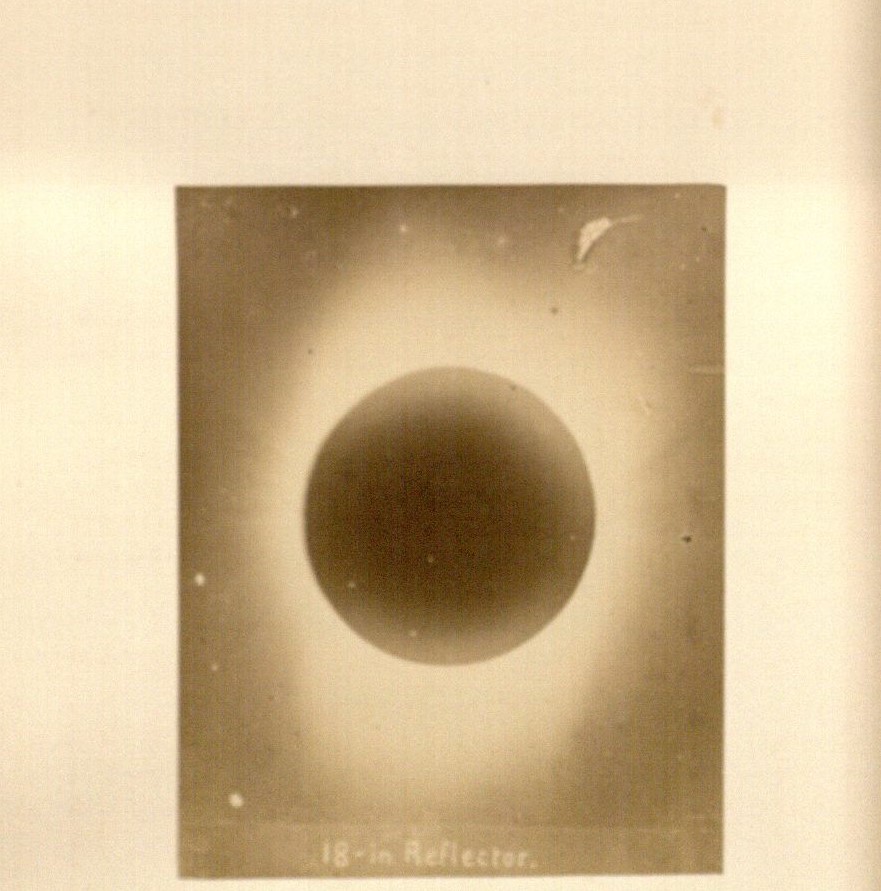

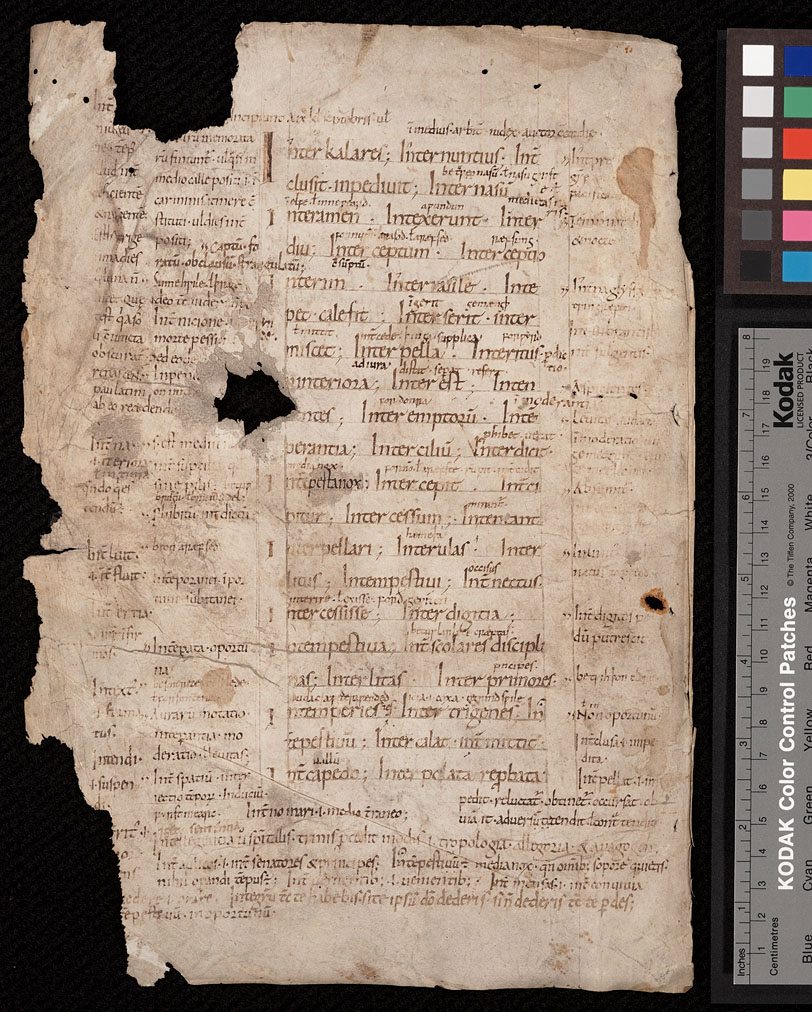

This image was developed using the negative from the exposure

created with the 18-inch reflector. Report on the Total Eclipse of the Sun,

Observed at Cayenne, French Guiana, South America, December 22, 1889

by S.W. Burnham and J.M. Schaeberle. Sacramento: A.J. Johnston,

Supt. State Printing, 1891. Call Number: C13311. Click images to enlarge.

The first report is from the Lick Observatory team’s visit to Cayenne, French Guiana, South America in 1889. The team left New York and traveled via boat to South America to observe and document the total solar eclipse on December 22nd. Despite some initial concerns about the weather, they were able to use several different lenses to create exposures of the eclipse that were later developed for further study.

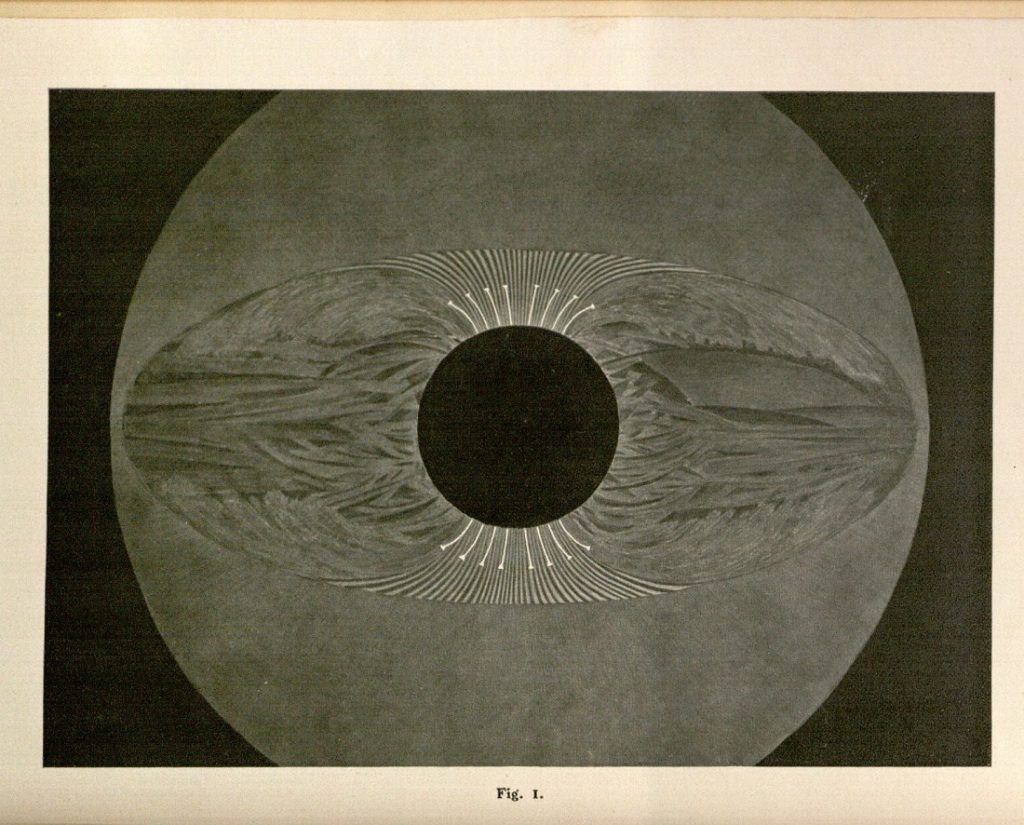

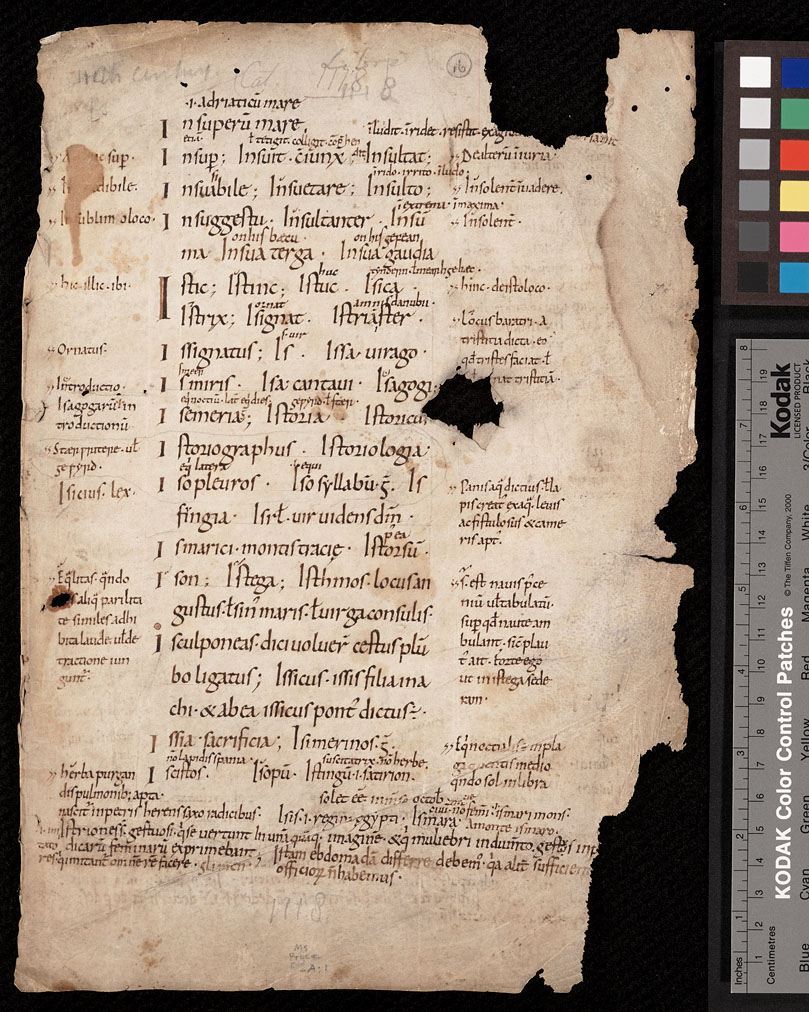

The image shows what Charles Howard experienced when looking through

the telescope at the moment of the eclipse. Total Eclipse of the Sun,

May 28, 1900, Observed at Winton, North Carolina by Charles P. Howard.

Hartford, Conn.: R.S. Peck & Co., printers and engravers, 1900.

Call Number: C13310. Click images to enlarge.

The second report is from Charles P. Howard’s visit to Winton, North Carolina, for the total solar eclipse in 1900. Howard joined the Trinity College team to observe and document the eclipse on May 28. Howard’s report also included images – created by the author – to convey his observations. His recorded thoughts show that he felt his images paled in comparison to the actual spectacle of the eclipse: ‘The view through the telescope, however, was far grander than the naked eye view and most awe-inspiring. Around the Sun was an appearance that almost made one exclaim, ‘the Sun is an enormous magnet, alive and hard at work.’” His illustration attempts to show the radiating waves he saw around the sun at the time of the eclipse.

If you are interested in learning more about the science behind a total solar eclipse, please take a look at Eclipse 101 from NASA!

Emily Beran

Public Services