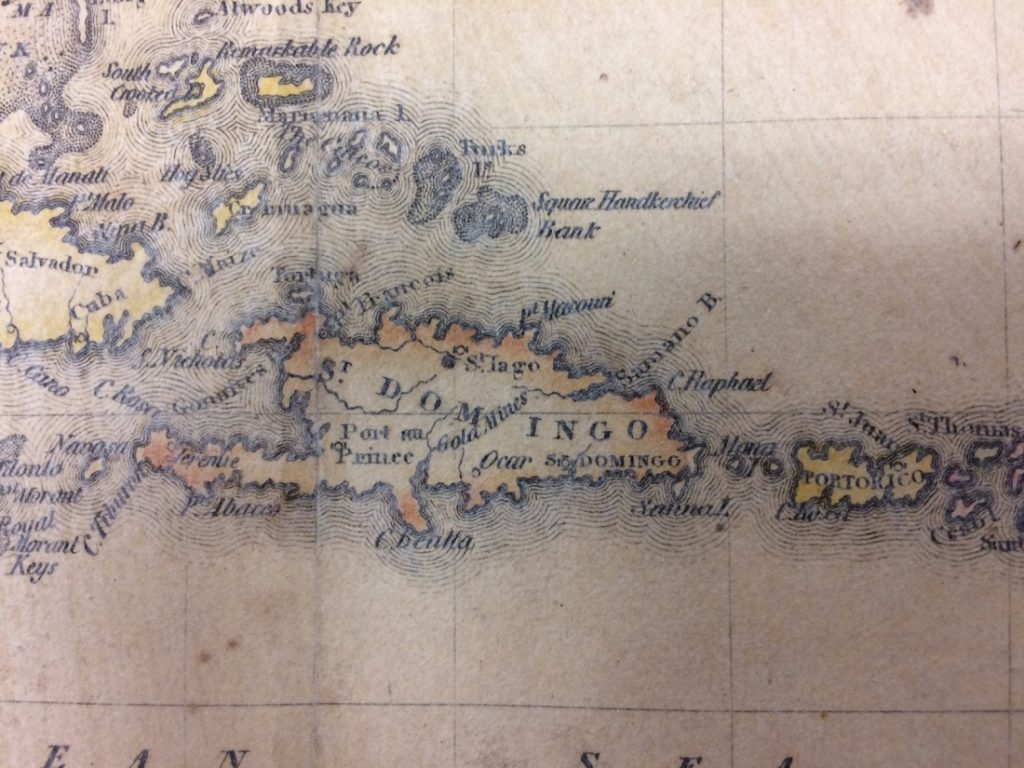

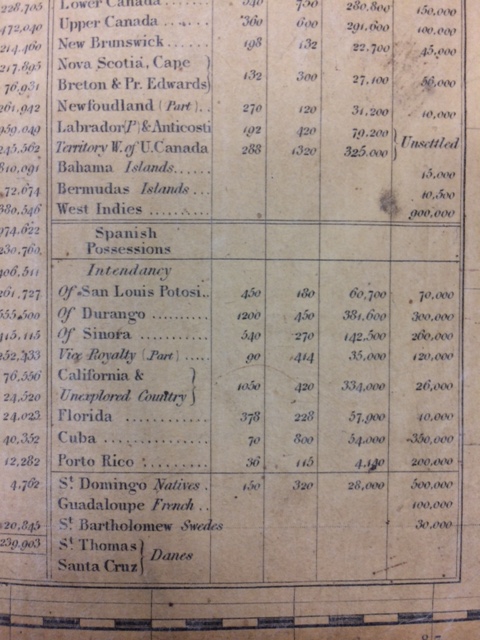

December has arrived and with it the winter holiday season! Since the holiday season means holiday parties, I wanted to look into hosting an oft forgotten type of affair – a lovely, elegant dinner party!

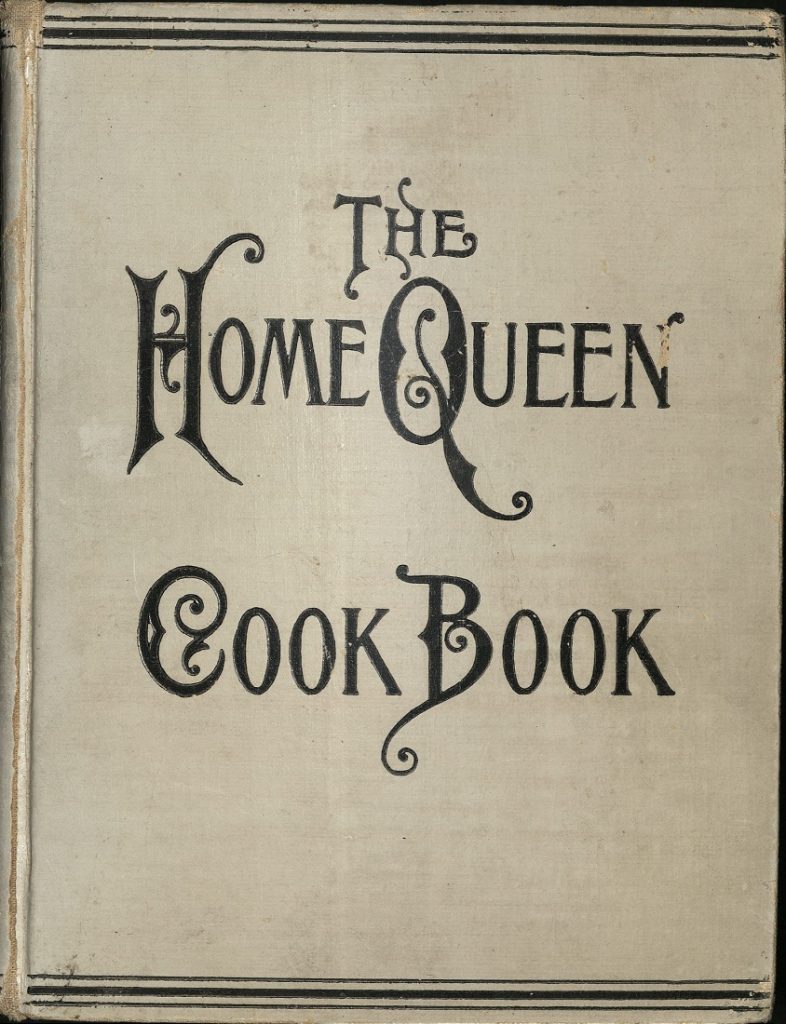

Personally, I do not have much experience with dinner parties so I decided to go to the best source I could find: The “Home Queen” Cook Book. Compiled during the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, The “Home Queen” Cook Book features recipes, etiquette, and entertaining suggestions from “over two hundred World’s Fair lady managers, wives of governors, and other ladies of position and influence.” Armed with the advice of these many esteemed ladies, I set out to see if I could recreate an elegant dinner party from generations past. What follows is a story of research, abandoned dreams, and a final feeble attempt to do anything I had originally hoped to accomplish.

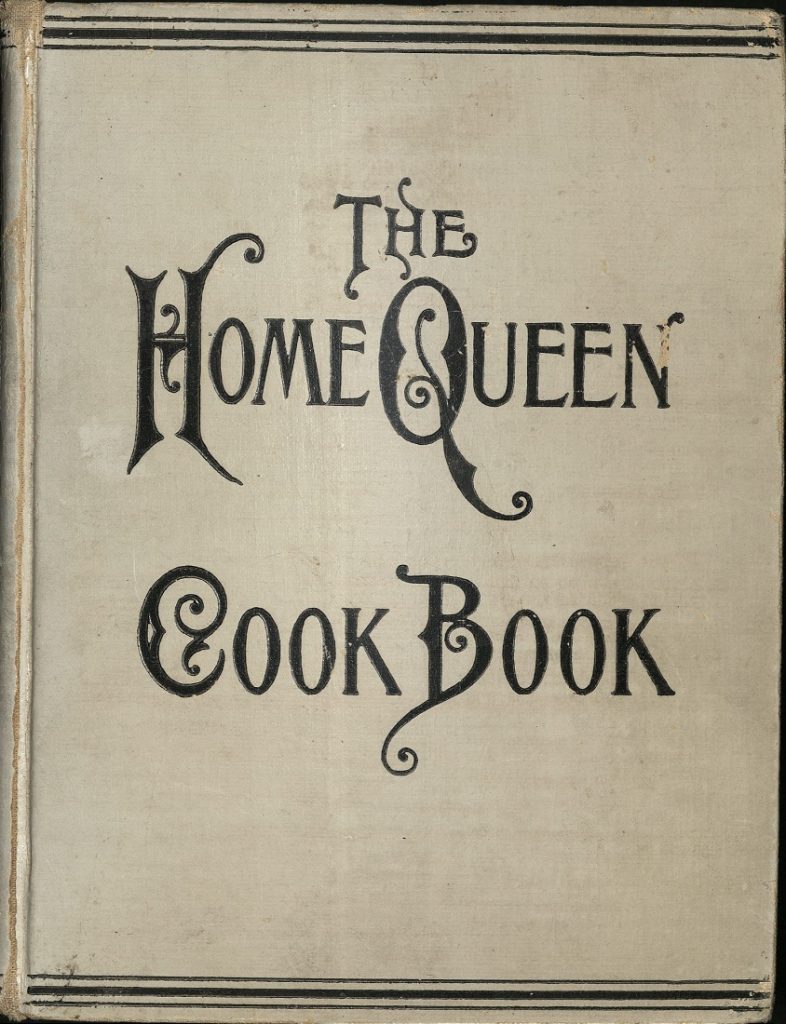

The cover of The “Home Queen” Cook Book, 1901.

Call Number: Galloway C35. Click image to enlarge.

Now, I do not know what everyone else pictures when they think of a dinner party, but I was envisioning an elegantly set table with beautiful linens and fine china to hold a magnificent multi-course meal. With that image in mind, I immediately began examining the section on “Party Suppers” in The “Home Queen” Cook Book. That sounds like the place to start, right? And what did I learn? First, a “party supper” and a dinner party are not synonymous. A party supper is much less formal than what I was expecting when I read the heading:

An evening party… would assemble quite early in the evening. This would give plenty of time for social intercourse, music and innocent amusements. Refreshments might be carried around on trays, and the guests served with cake, coffee or lemonade. Fine large napkins should first be handed around. These should be spread on the knees to receive the plates afterward furnished. Delicate sandwiches of chopped tongue, spread thinly on sandwich biscuits, or the white meat of turkey or check are very nice for such entertainments. Ice cream, confectionery, and ripe fruit of any kind may be served.

I liked the idea of this informal gathering, which was meant to “facilitate conversation, ease, and the choosing of congenial companions out of mixed gatherings at large parties.” What more could you want from a festive holiday party? However, I still had the aforementioned picture of a dinner party in my mind. This prompted me to look to the sections on “The Mid-Day Meal” and “The Evening Meal” in the book, hoping to find any information that might be of use. Lo and behold, I found exactly what I was picturing in “The Mid-Day Meal” section! In it was everything I could ever want to know about table settings, the most appropriate food choices, even how to properly invite your guests to the affair. Before spending a great deal of time on the overwhelming amount of food described, I decided to focus first on the most basic aspect of the evening: a proper table setting.

After reading the descriptions of the proper linens, plates, crystal, and silver, I realized that just setting the table would cost a small fortune. The proper “snow white” table linen made of the suggested “handsome Irish damask” would easily cost over $100 for a small tablecloth. Any attempt at recreating the quality of a proper dinner table setting was clearly out of reach.

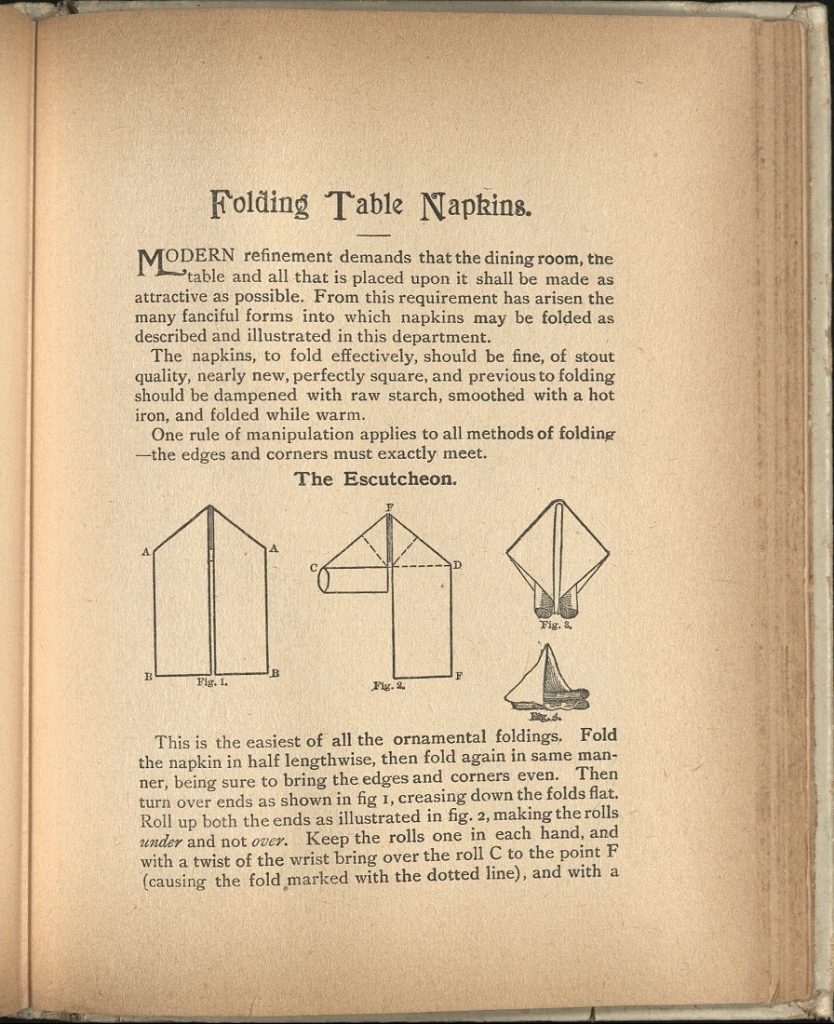

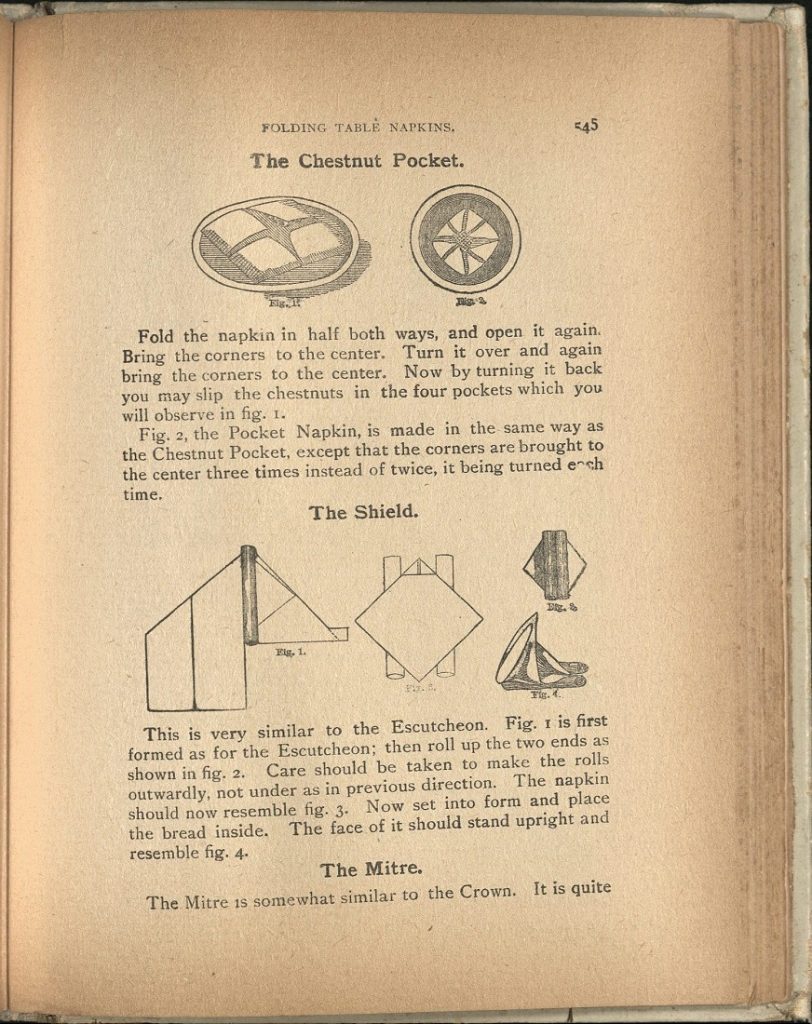

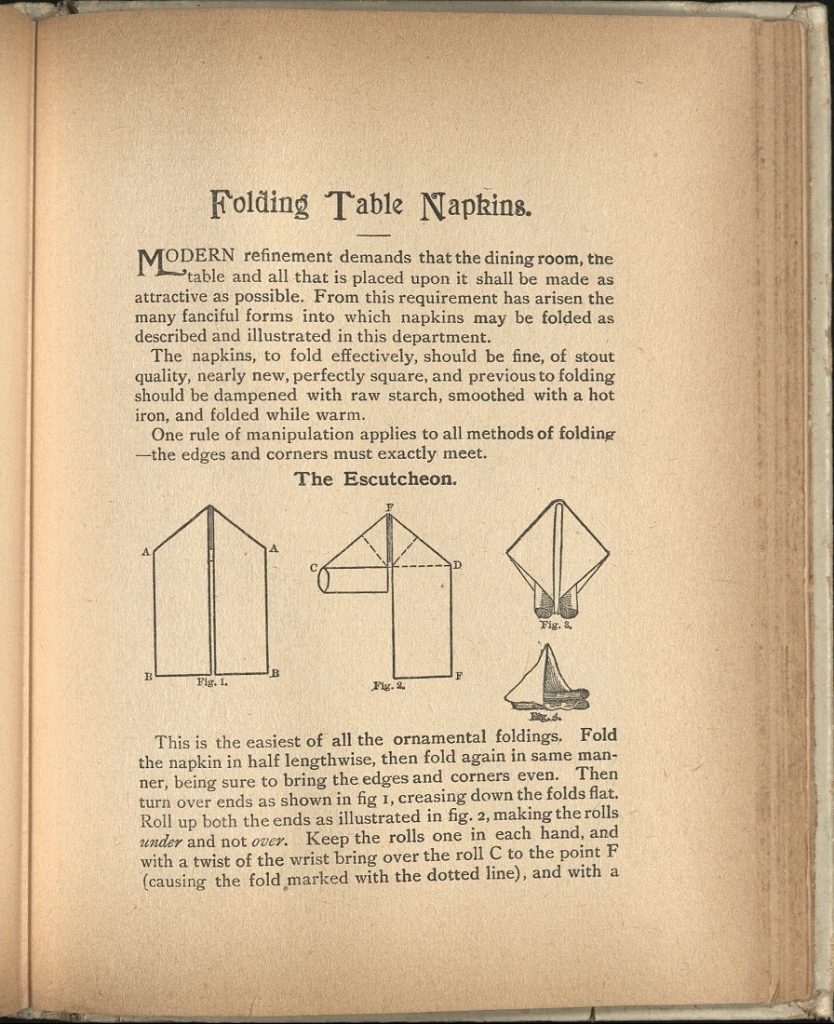

“Ok,” I thought to myself, “If the expected quality is unmanageable, what can I do that would dress up a somewhat subpar table setting so that it at least looks elegant?” Returning to the book, I found the perfect remedy: an artfully folded napkin. Aided by the “Folding Table Napkins” section, I began my attempt to create anything that might give me the air of sophistication I had hoped to achieve when I originally formed this brilliant plan of mine.

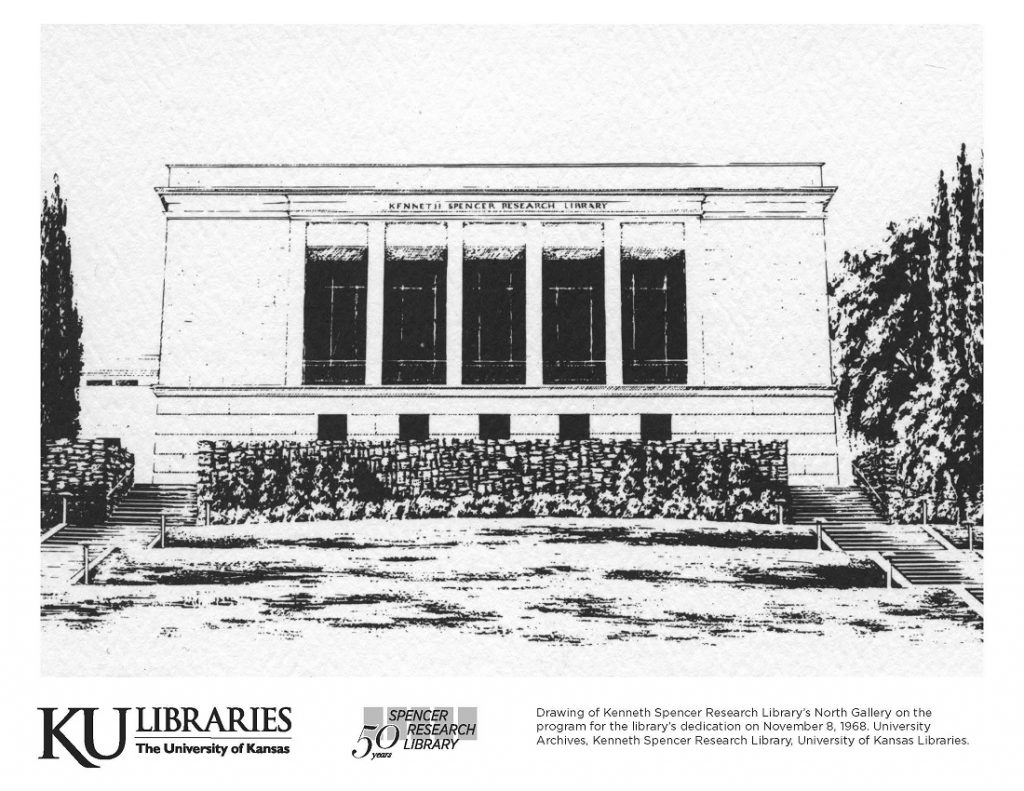

Escutcheon napkin fold diagram and instructions in

The “Home Queen” Cook Book, 1901.

Call Number: Galloway C35. Click image to enlarge.

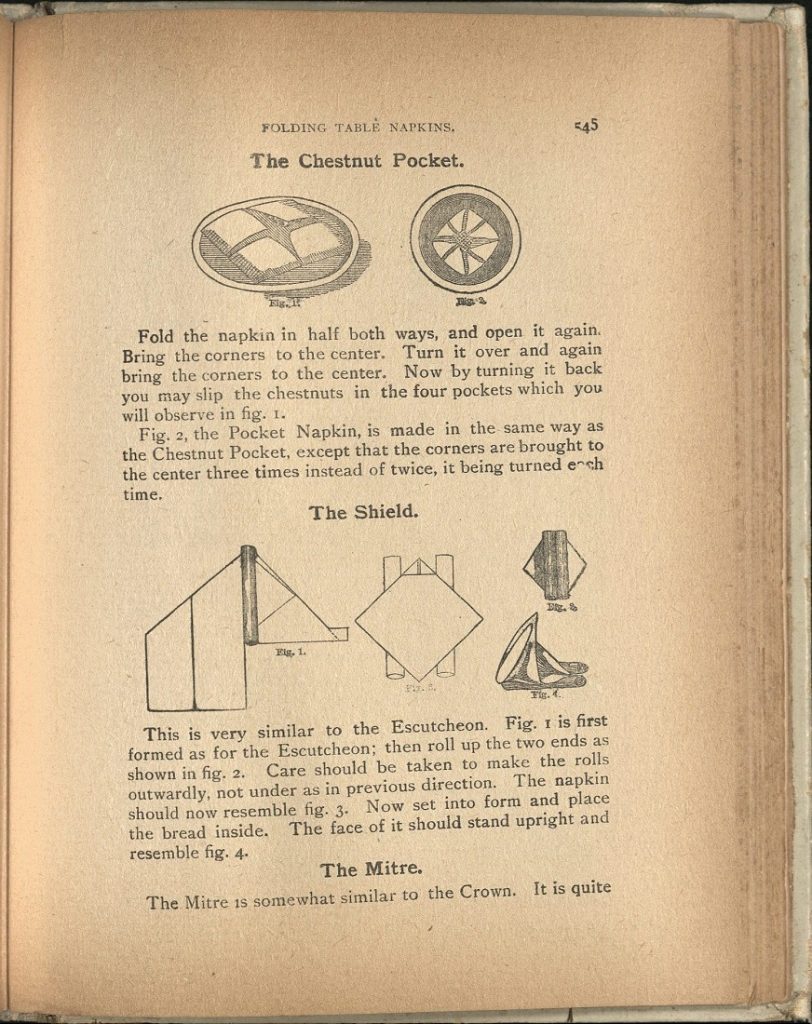

The “Home Queen” Cook Book features no less than twenty-one different napkin-folding techniques to help ensure that “the dining room, the table and all that is placed upon it shall be made as attractive as possible.” With such a plethora of options – all with detailed instructions and pictures to guide me – I thought I had finally found the perfect starting point on my way to my dream dinner party. Unfortunately, my optimism and confidence were quickly destroyed after attempting only two of the possible folds: the Escutcheon (picture above) and the Chestnut Pocket (pictured below).

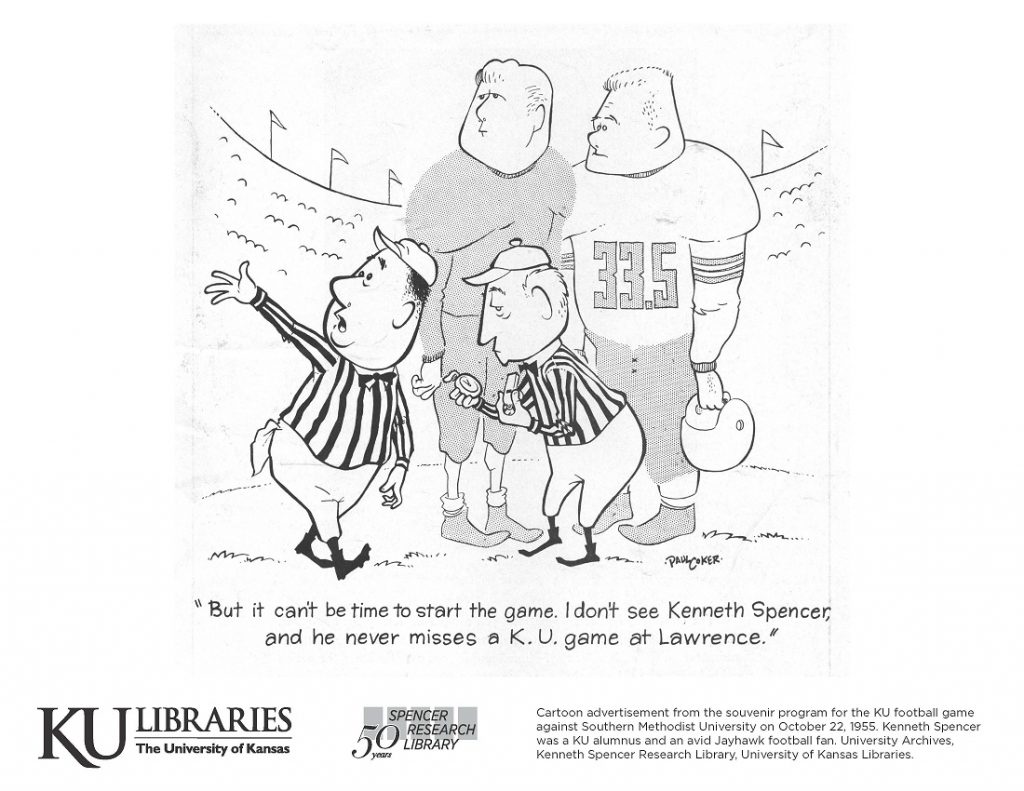

The Chestnut Pocket napkin fold diagram and instructions in

The “Home Queen” Cook Book, 1901.

Call Number: Galloway C35. Click image to enlarge.

The Escutcheon: Described as “the easiest of all the ornamental foldings,” the Escutcheon was the beginning of the end for me. It was here I learned that the instructions to starch and iron the napkins immediately before folding was not a suggestion but truly an absolute requirement. After close to a half an hour of intense labor and a great deal of swearing, I finally managed to produce… something.

My attempt at the Escutcheon napkin fold. Click image to enlarge.

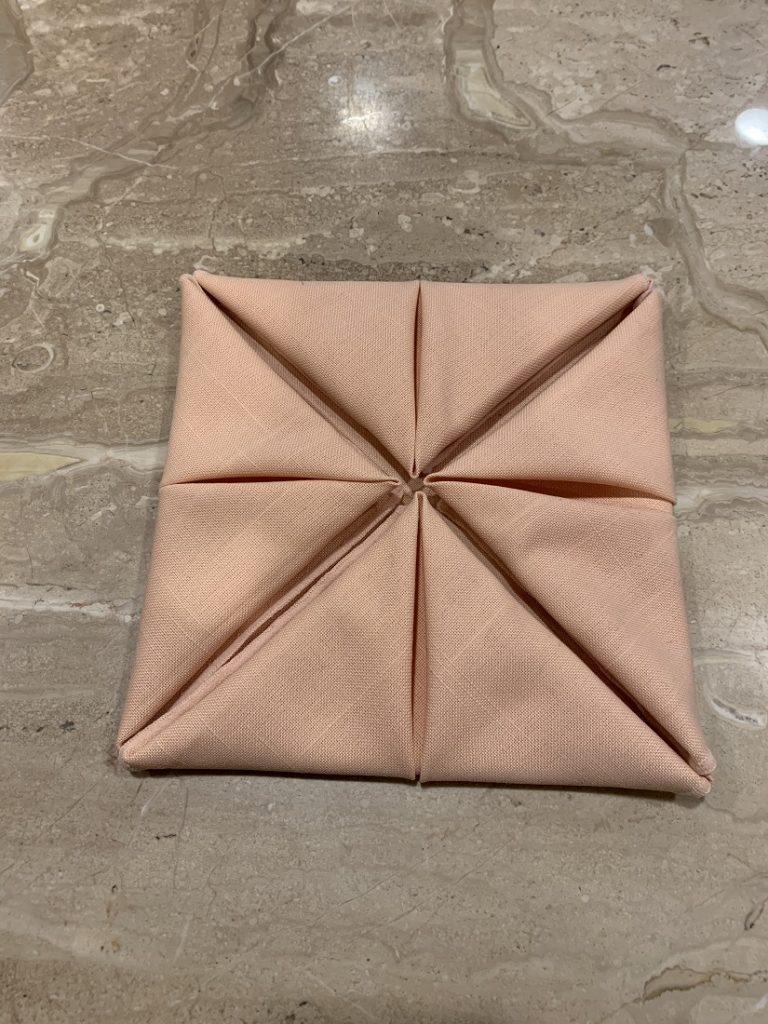

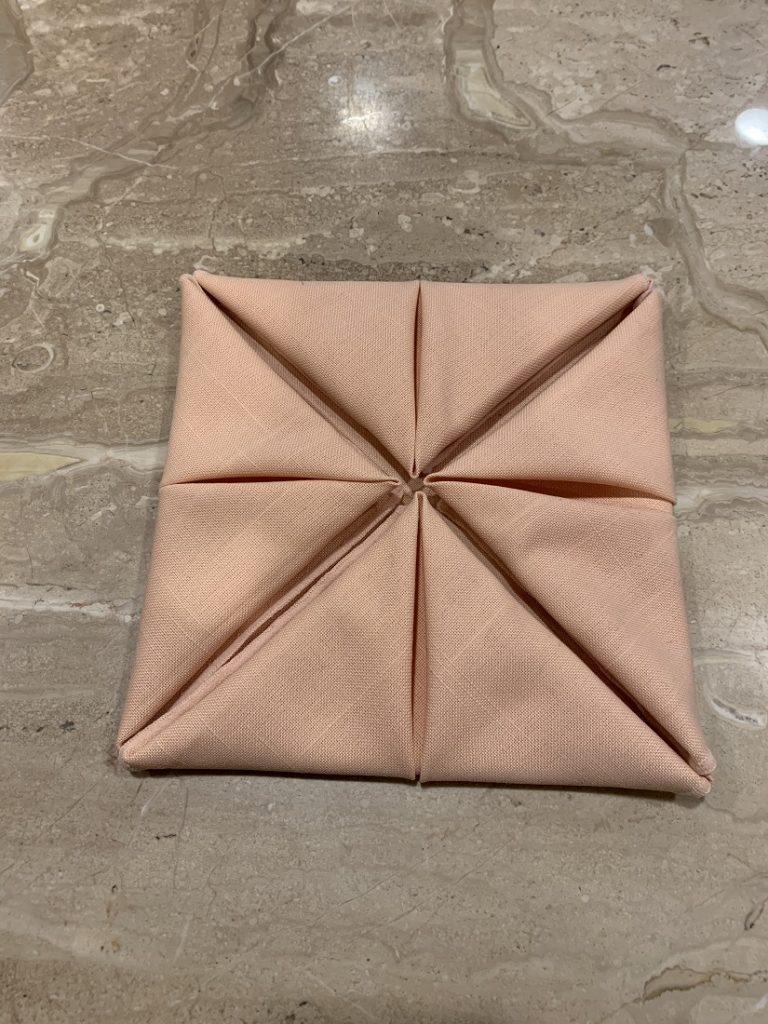

The Chestnut Pocket: My attempt to regaining any semblance of dignity after being so embarrassingly defeated by the Escutcheon finally yielded a positive result for me! I even took it a step beyond the Chestnut Pocket and created the Pocket Napkin. I found that the secret to success lay in finding a napkin-folding technique that did not need to stand up. With this revelation, I managed to produce the following creation:

My successful attempt at the Pocket napkin fold

(a variation on the Chestnut Pocket napkin fold).

Click image to enlarge.

So after all of this – the research, the numerous disappointments, the defeat, and eventual triumph – I am sure you must be wondering: will I be hosting my envisioned elegant dinner party this holiday season? To put it succinctly, absolutely not. There is only so much embarrassment by fabric I am willing to put myself through in the name of holiday entertaining.

Emily Beran

Public Services